A Comprehensive Guide to Immunocytochemistry: From Basic Protocol to Advanced Troubleshooting for Cell Culture Research

This article provides a complete guide to immunocytochemistry (ICC) for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

A Comprehensive Guide to Immunocytochemistry: From Basic Protocol to Advanced Troubleshooting for Cell Culture Research

Abstract

This article provides a complete guide to immunocytochemistry (ICC) for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of ICC, a detailed step-by-step protocol for adherent and suspension cells, advanced troubleshooting for common issues like weak staining and high background, and essential validation techniques to ensure reproducible, publication-quality results. The content synthesizes current best practices to empower users in visualizing protein localization and function within cultured cells.

Understanding Immunocytochemistry: Core Principles and Preparatory Steps for Cell Culture

What is ICC? Defining Immunocytochemistry and Its Relation to Immunofluorescence

Immunocytochemistry (ICC) is a common laboratory technique used to anatomically visualize the localization of a specific protein or antigen in cells by using a specific primary antibody that binds to it [1]. This method allows researchers to evaluate whether cells in a particular sample express the antigen in question and, when an immunopositive signal is found, to determine which sub-cellular compartments are expressing the antigen [1] [2]. The technique has become fundamental in biomedical research, particularly for diagnosing and classifying various cancers, including lymphomas, leukemias, and breast cancer, by identifying specific antigens that help determine the origin of undifferentiated tumors [3].

The development of immunocytochemistry dates back to 1941 when Albert Coons pioneered the use of fluorescent antibodies to visualize antigens in tissues, which is considered the birth of immunofluorescence [4]. This breakthrough paved the way for subsequent innovations, including the development of monoclonal antibody production using hybridoma technology in 1975 by Georges Köhler, César Milstein, and Niels K. Jerne, which revolutionized the field by providing a consistent supply of highly specific antibodies [4].

Table 1: Key Comparisons Between Protein Detection Techniques

| Parameter | ICC/IHC | Western Blot | ELISA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Fixed cells on coverslip (ICC); Fixed tissue section (IHC) [4] | Lysed and denatured protein [4] | Lysed cells or biological fluids [4] |

| Protein State | In situ, but fixed [4] | Denatured [4] | Native, unfixed [4] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Easily up to 4 targets [4] | Possible with fluorescent multiplexing [4] | Typically requires bead-based immunoassays [4] |

| Sensitivity | Medium [4] | High [4] | High [4] |

| Subcellular Compartmentalization | Highly suitable [4] | Limited to subcellular fractionation [4] | Limited to subcellular fractionation [4] |

ICC vs. IHC vs. IF: Critical Distinctions

While the terms immunocytochemistry (ICC), immunohistochemistry (IHC), and immunofluorescence (IF) are sometimes used interchangeably, they represent distinct techniques with important differences [5].

Immunocytochemistry (ICC) specifically refers to the immunostaining of cultured cell lines or primary cells, including smears, swabs, and aspirates [5]. In ICC, samples consist of intact cells that have had most of their surrounding extracellular matrix removed [1]. This includes individual cells that have been isolated from a block of solid tissue, cells grown within a culture, cells deposited from suspension, or cells taken from a smear [1].

Immunohistochemistry (IHC), in contrast, involves tissue immunostaining of either formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) or frozen tissue [5]. In IHC, samples are sections of biological tissue where each cell is surrounded by tissue architecture and other cells normally found in the intact tissue [1]. This preservation of tissue context makes IHC particularly valuable for understanding the physiological context of protein expression.

Immunofluorescence (IF) describes the detection method rather than the sample type. IF uses fluorophore-conjugated antibodies for detection, as opposed to chromogenic detection methods that use enzymes to produce colored precipitates [5]. From a conceptual scope, immunofluorescence has a broader range of coverage and includes both immunohistochemistry and immunocytochemistry [2]. In other words, IHC and ICC can both utilize IF as their detection methodology.

Table 2: Comparison of ICC, IHC, and IF Techniques

| Aspect | Immunocytochemistry (ICC) | Immunohistochemistry (IHC) | Immunofluorescence (IF) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Type | Cultured cells, cell suspensions, smears, aspirates [5] | Tissue sections (FFPE or frozen) [5] | Detection method, not a sample type [2] [5] |

| Cellular Context | Isolated cells without native extracellular matrix [1] | Cells in their native tissue architecture [1] | Applicable to both cells and tissues [2] |

| Primary Applications | Subcellular localization, co-localization studies, expression profiles [4] | Diagnostic pathology, tumor classification, tissue distribution [3] | Protein distribution, multi-target visualization, high-resolution imaging [4] |

| Common Detection Methods | Both chromogenic and fluorescent [5] | Both chromogenic and fluorescent [5] | Exclusive use of fluorophores [5] |

Relationship Between ICC, IHC, and IF

Core Principles and Methodologies

Antibody-Antigen Interaction in ICC

The fundamental principle underlying ICC is the specific binding between an antibody and its target antigen [6]. Antibodies are immunoglobulin proteins with a variable region (Fab portion) that binds the epitope part of the antigen and a constant region (Fc portion) that is specific to the animal in which the antibody was raised [7]. For example, a rabbit anti-tubulin antibody binds the protein tubulin with its variable region and can be bound on its constant region by an anti-rabbit secondary antibody [7].

This specific binding allows researchers to target virtually any cellular protein with high precision. The location of fluorescence will vary according to the target molecule, appearing externally for membrane proteins and internally for cytoplasmic proteins [1]. When combined with confocal microscopy, immunofluorescence becomes a powerful technique for studying the location of proteins and dynamic processes such as exocytosis and endocytosis [1].

Detection Methods: Direct vs. Indirect

ICC detection can be performed using either direct or indirect methods, each with distinct advantages [6]:

Direct ICC involves the use of a primary antibody directly conjugated to a detectable tag, such as a fluorescent molecule or gold particles [1] [6]. This method is rapid, requiring only a single incubation step, and minimizes potential cross-reactivity in multiplex experiments [8]. However, it typically offers lower sensitivity as there is no signal amplification [5].

Indirect ICC utilizes an unlabeled primary antibody followed by a labeled secondary antibody that recognizes the primary antibody [1] [6]. This method provides signal amplification since multiple secondary antibodies can bind to a single primary antibody, significantly enhancing sensitivity [5]. While it requires an additional incubation step and careful selection of host species to avoid cross-reactivity, the extensive commercial availability of labeled secondary antibodies makes this approach highly accessible and versatile [8].

ICC Detection Methodologies

Comprehensive ICC Protocol

Sample Preparation and Fixation

Proper sample preparation is critical for successful ICC. Cells are typically cultured directly on glass coverslips, which may be coated with substances like poly-L-lysine, poly-D-lysine, or gelatin to enhance cell adhesion [6] [9]. For suspension cells, alternative methods such as cytospin centrifugation can be used to concentrate cells onto glass slides [1].

Fixation preserves cell morphology and antigenicity by immobilizing cellular components. The choice of fixative depends on the target antigen and its cellular localization:

- Aldehyde-based fixatives (e.g., 2-4% paraformaldehyde): Cross-link proteins, preserving structure well but potentially masking some epitopes; requires 10-20 minutes incubation at room temperature [6] [9].

- Organic solvents (e.g., methanol, ethanol, acetone): Precipitate proteins and simultaneously permeabilize membranes; typically require 5-10 minutes incubation at -20°C [6].

Optimal fixation time must be determined empirically, as over-fixation can mask epitopes while under-fixation may lead to poor epitope preservation [6].

Permeabilization and Blocking

Permeabilization is essential when using aldehyde fixatives to allow antibody access to intracellular targets by partially solubilizing cell membranes [6]. This step is often unnecessary when using organic solvents as they simultaneously fix and permeabilize cells [6].

Common permeabilization agents include:

- Harsh detergents (e.g., Triton X-100, NP-40 at 0.1-0.2%): Effective for most intracellular targets but may damage membrane-associated antigens [6].

- Mild detergents (e.g., Tween-20, saponin, digitonin at 0.2-0.5%): Better for preserving membrane integrity [6] [8].

Blocking reduces non-specific antibody binding using protein solutions such as 2-10% normal serum from the secondary antibody host species or bovine serum albumin (BSA) [6] [9]. Blocking typically requires 1-2 hours at room temperature [6]. The blocking solution should not contain serum from the host animal of the primary antibody, as this would increase background staining [6].

Antibody Incubation and Detection

Primary antibody incubation is performed using antibodies diluted in appropriate buffers, often containing BSA and small amounts of detergent [6] [9]. Incubation conditions vary:

- 1 hour at room temperature for strong, abundant antigens [9].

- Overnight at 2-8°C for weak or scarce antigens [9].

Secondary antibody incubation uses species-specific antibodies conjugated to fluorophores, typically incubated for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark [6] [9]. From this step forward, samples must be protected from light to prevent fluorophore photobleaching [9].

Counterstaining and mounting are final steps where nuclear stains like DAPI (4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) are applied for 2-5 minutes to visualize cell nuclei [9]. Samples are then mounted using anti-fade mounting medium to preserve fluorescence during storage and visualization [9].

Complete ICC Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for ICC Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Fixatives | 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) [6], Methanol [6], Acetone [6] | Preserve cell morphology and immobilize antigens; PFA cross-links proteins, while organic solvents precipitate proteins [6]. |

| Permeabilization Agents | Triton X-100 [6], Tween-20 [6], Saponin [8] | Solubilize membrane lipids to allow antibody access to intracellular targets; concentration and incubation time require optimization [6]. |

| Blocking Agents | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) [6], Normal Serum [6] [9] | Reduce non-specific antibody binding; normal serum should match the host species of secondary antibodies [6]. |

| Detection System | Primary Antibodies [6], Fluorophore-conjugated Secondary Antibodies [9] | Specifically bind target antigens (primary) and amplify signal (secondary); multiple secondary antibodies bind each primary for signal amplification [5]. |

| Counterstains | DAPI [9], Propidium Iodide [10], Hoechst 33342 [10] | Label nuclear DNA for reference; DAPI is most common with absorption maximum at 358 nm and emission at 461 nm [9]. |

| Mounting Media | Anti-fade Mounting Medium [9] | Preserve fluorescence and prevent photobleaching during storage and visualization [9]. |

| E3 Ligase Ligand-linker Conjugate 108 | E3 Ligase Ligand-linker Conjugate 108, MF:C22H26ClN3O4, MW:431.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| E3 Ligase Ligand-linker Conjugate 151 | E3 Ligase Ligand-linker Conjugate 151, MF:C31H40N6O4S, MW:592.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Critical Experimental Considerations

Appropriate Controls for ICC

Proper controls are essential for validating ICC results and are required for publication in scientific journals [7]. Three main types of controls should be implemented:

Primary antibody controls demonstrate the specificity of primary antibody binding to the antigen [7]. The most rigorous approach uses genetic manipulation, such as:

- Knockout controls: Tissue or cells from animals lacking the gene encoding the target antigen should show no labeling [7].

- Transfected cell lines: Cells expressing the antigen of interest serve as positive controls, while untransfected cells serve as negative controls [7].

- Alternative methods include immunoblotting to confirm antibody specificity or colocalization with a second independent antibody targeting different epitopes on the same protein [7].

Secondary antibody controls show that labeling is specific to the primary antibody [7]. This is typically done by omitting the primary antibody while including all other steps, which should result in no specific staining [9] [7].

Label controls ensure that observed labeling results from the added label rather than endogenous sources [7]. This is particularly important for fluorescent detection, where some cells may contain endogenous fluorophores that could create false positives.

Optimization and Troubleshooting

Successful ICC often requires optimization of several parameters:

Antibody concentration must be titrated to achieve strong specific signal with minimal background. Commercial antibodies typically provide recommended starting dilutions, but these may require adjustment for specific applications [9].

Fixation conditions need careful optimization, as over-fixation can mask epitopes while under-fixation may lead to poor morphology and antigen preservation [6]. When epitopes are masked by fixation, antigen retrieval techniques may be employed, though these require caution with cell samples as the exposure conditions can be harsh [8].

Multiplex ICC requires careful experimental design when detecting multiple antigens simultaneously:

- Primary antibodies must be raised in different host species to prevent cross-reactivity of secondary antibodies [8].

- Fluorophores with minimal spectral overlap should be selected based on the available microscope filter sets [8].

- Staining intensity should be balanced, as extremely bright signals can bleed into adjacent channels [8].

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

ICC has evolved significantly from its origins in the 1940s, with current applications extending far beyond simple protein localization. Modern implementations include:

Multi-parametric experiments that simultaneously detect several antigens, enabled by the broad availability of fluorophores and advancements in fluorescence microscopy [4]. Current systems can routinely detect 4 or more targets in a single sample, with more possible through techniques like spectral unmixing or sequential probing [4].

Live-cell imaging applications where antibodies or other labeling strategies are used to track dynamic processes in real-time, though this typically requires specialized labeling approaches as traditional ICC uses fixed samples.

Super-resolution techniques that break the diffraction limit of light microscopy, enabling visualization of subcellular structures with unprecedented detail when combined with ICC [4].

The continued development of brighter, more photostable fluorophores, along with advances in microscopy technology and image analysis software, promises to further expand the capabilities and applications of immunocytochemistry in biomedical research and drug development [4] [8].

Immunocytochemistry (ICC) is a cornerstone technique in biomedical research, enabling the visualization and localization of specific proteins within individual cultured cells. This powerful method relies on the specific binding of antibodies to target proteins (antigens), followed by detection using fluorescent labels (fluorophores). The synergy between these two components allows researchers to precisely determine the subcellular distribution, expression levels, and dynamic behavior of proteins in their native cellular context, providing invaluable insights into protein function, cell signaling pathways, and disease mechanisms. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering these principles is essential for generating reproducible, high-quality data in studies ranging from basic cell biology to preclinical drug evaluation.

The fundamental process involves exploiting the immune system's exquisite specificity, where antibodies recognize and bind to unique three-dimensional structures (epitopes) on target proteins. By conjugating these antibodies to fluorophores—molecules that absorb light at specific wavelengths and emit light at longer wavelengths—researchers can transform invisible molecular interactions into visible signals detectable by fluorescence microscopy. This combination forms the basis for not only single-protein detection but also sophisticated multiplexing experiments where multiple proteins can be visualized simultaneously within the same cell, revealing complex interaction networks and spatial relationships that drive cellular function.

Core Principles of Antibody-Antigen Specificity

Antibody Structure and Epitope Recognition

Antibodies, particularly immunoglobulin G (IgG), are Y-shaped proteins generated by the immune system to recognize foreign molecules with high specificity. In ICC, this natural recognition system is harnessed using antibodies raised against specific protein targets. The tip of each antibody arm contains hypervariable regions that form the antigen-binding site, which recognizes a specific portion of the target protein called an epitope. This precise molecular complementarity enables antibodies to distinguish between even highly similar proteins, providing the foundation for specific detection in complex cellular environments.

- Primary Antibodies: These bind directly to the protein of interest and are typically produced by immunizing host animals (e.g., rabbits, mice, goats) with the target antigen. Monoclonal antibodies originate from a single B-cell clone and recognize a single epitope, ensuring high specificity, while polyclonal antibodies represent a mixture of antibodies recognizing different epitopes on the same antigen, often providing stronger signals.

- Secondary Antibodies: These recognize and bind to the constant region (Fc) of primary antibodies, amplifying the signal and providing a flexible detection system. Since secondary antibodies are conjugated to fluorophores, a single primary antibody can be used with different secondary antibodies to produce different detection signals, making this indirect method highly versatile and sensitive [11] [6].

Key Factors Influencing Antibody Specificity

Several critical factors determine the success and specificity of antibody-antigen interactions in ICC:

- Epitope Availability: The target epitope must be accessible to the antibody after cell fixation and permeabilization. Some fixation methods can mask epitopes by altering protein conformation.

- Antibody Affinity and Avidity: Affinity refers to the strength of interaction between a single antibody binding site and its epitope, while avidity describes the combined strength of multiple binding interactions. High-affinity antibodies provide stronger, more specific signals.

- Species Compatibility: Primary and secondary antibodies must be compatible—secondary antibodies must be raised against the species in which the primary antibody was produced [11] [12].

- Validation: Antibodies must be validated for ICC applications to ensure they recognize the correct target in fixed and permeabilized cells, as performance can vary significantly between techniques like ICC, western blot, and immunohistochemistry [13].

Fluorescence Detection and Signal Generation

Fluorophore Properties and Selection Criteria

Fluorophores are molecules that absorb light at specific wavelengths and then emit light at longer wavelengths (lower energy) through the process of fluorescence. When selected and implemented correctly, they provide the detectable signal that reveals the location and quantity of the target protein. Key optical properties must be considered when choosing fluorophores for ICC:

- Excitation and Emission Spectra: The specific wavelengths at which a fluorophore absorbs (excitation maximum) and emits (emission maximum) light. These determine which microscope filters and light sources are needed.

- Stokes Shift: The difference between the excitation and emission maxima. Larger Stokes shifts reduce background signal by minimizing overlap between excitation and emission wavelengths.

- Quantum Yield: The efficiency with which a fluorophore converts absorbed photons into emitted photons. Higher quantum yields produce brighter signals.

- Photostability: The resistance of a fluorophore to photobleaching (permanent loss of fluorescence) during illumination. More photostable fluorophores allow longer imaging sessions.

Table 1: Common Fluorophores and Their Properties

| Fluorophore | Excitation Max (nm) | Emission Max (nm) | Relative Brightness | Photostability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAPI | 358 | 461 | Medium | High |

| FITC | 495 | 519 | Medium | Low |

| TRITC | 557 | 576 | Medium | Medium |

| Cy3 | 554 | 568 | High | Medium |

| Alexa Fluor 488 | 495 | 519 | High | High |

| Alexa Fluor 555 | 555 | 565 | High | High |

| Texas Red | 595 | 615 | High | Medium |

Signal Amplification and Detection Sensitivity

The indirect ICC method, using a primary antibody followed by a fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody, provides significant signal amplification as multiple secondary antibodies can bind to a single primary antibody. This amplification enhances detection sensitivity, enabling visualization of low-abundance proteins. The high specificity of this system, when properly optimized, ensures that the fluorescent signal accurately represents the distribution of the target protein with minimal background noise [11] [6].

Advanced fluorophores such as quantum dots (QDs) offer superior properties for detection, including high quantum yield, exceptional photostability, and narrow, symmetric emission spectra. These properties make QDs particularly valuable for multiplexed experiments detecting multiple proteins simultaneously. However, conjugating antibodies with QDs requires specialized approaches, including site-specific and site-nonspecific conjugation methods, to maintain antibody functionality while exploiting the superior optical properties of nanomaterials [14].

Experimental Protocols for Immunocytochemistry

Sample Preparation and Fixation Protocol

Proper sample preparation is crucial for preserving cellular morphology and antigen integrity while ensuring antibody accessibility:

- Cell Culture: Grow cells on sterile glass coverslips (12-25mm depending on well plate size) to 50-70% confluency. For poorly adherent cells, use poly-D-lysine or other adhesion-coated coverslips to prevent detachment during processing [11] [15].

- Fixation: Aspirate culture media and gently wash cells 3x with PBS (5 minutes per wash, room temperature). Fix cells using one of the following methods:

- 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA): Incubate for 10 minutes at room temperature or 20 minutes at 4°C. Ideal for most proteins, preserves structure well.

- 100% Methanol: Pre-chill to -20°C, incubate for 5 minutes at room temperature. Simultaneously fixes and permeabilizes cells.

- Methanol/Acetone: 1:1 mixture chilled to -20°C, incubate for 5-10 minutes [11] [6].

- Post-fixation Handling: After fixation, wash cells 3x with PBS (5 minutes per wash). For long-term storage, keep samples in 0.1% sodium azide/PBS at 4°C for 1-2 weeks maximum [6].

Table 2: Fixation Methods and Their Applications

| Fixative | Concentration | Incubation Conditions | Best For | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | 4% in PBS | 10-20 min, RT or 4°C | Most intracellular proteins; preserves morphology | Requires permeabilization step |

| Methanol | 100% | 5-10 min, -20°C | Cytoskeletal proteins; nuclear antigens | Fixes and permeabilizes simultaneously; may destroy some epitopes |

| Acetone | 100% | 5-10 min, -20°C | Membrane proteins; viral antigens | Excellent penetration; may shrink cells |

| Ethanol | 95-100% | 5-10 min, -20°C | Selected nuclear antigens | Mild fixative; good for DNA/RNA detection |

Permeabilization and Blocking

- Permeabilization: Required when using PFA fixation to allow antibody access to intracellular epitopes. Incubate cells with 0.1-0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 minutes at 4°C. For membrane-associated proteins, use milder detergents like Tween-20 or saponin to preserve membrane integrity [11]. Note: Permeabilization is unnecessary after methanol or acetone fixation [6].

- Blocking: Critical for reducing non-specific antibody binding and minimizing background. Incubate samples with blocking buffer (e.g., 5% normal serum from the secondary antibody host species, 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Alternative blocking buffers include 1-5% BSA in PBS. The blocking serum should always match the host species of the secondary antibody [11] [15].

Antibody Incubation and Detection

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Prepare primary antibody at appropriate dilution in blocking buffer (typical range: 5-20 µg/mL). Incubate samples in a humidified chamber either overnight at 4°C or for 2 hours at room temperature. For multiple primary antibodies from different host species, simultaneous incubation is possible [11] [6].

- Washing: Remove unbound primary antibody by washing 3x with PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 (PBS-T).

- Secondary Antibody Incubation: Prepare fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody at appropriate dilution (typically 1:500-1:1000) in blocking buffer. Incubate samples for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark. From this point forward, minimize light exposure to prevent fluorophore photobleaching [11] [15].

- Final Washes: Wash samples 3x with PBS-T (5 minutes per wash) to remove unbound secondary antibody.

Counterstaining, Mounting, and Imaging

- Counterstaining: Incubate samples with 1 µg/mL DAPI or other nuclear stain for 5 minutes at room temperature to visualize cell nuclei [11].

- Mounting: Place a drop of anti-fade mounting medium on a microscope slide. Carefully invert coverslip (cells facing down) onto mounting medium. Gently remove excess medium and seal edges with nail polish if required [15].

- Imaging: Visualize cells under a fluorescence microscope with appropriate excitation sources and filter sets. Acquire images as soon as possible after processing, though slides can be stored at 4°C in the dark for short periods [11].

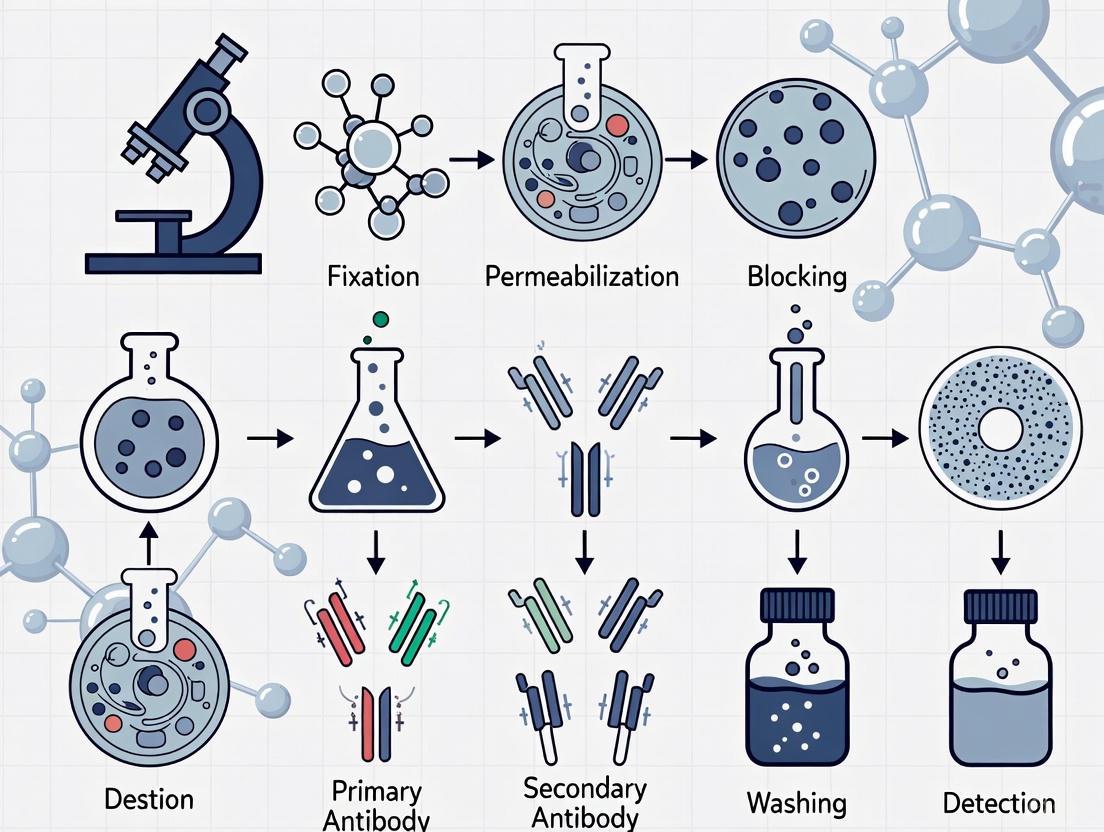

Visualization of ICC Workflow and Principles

The following diagram illustrates the key steps and molecular interactions in the indirect immunocytochemistry workflow:

Immunocytochemistry Workflow and Molecular Interactions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful immunocytochemistry requires carefully selected reagents optimized for each step of the process. The following table details essential materials and their functions in ICC experiments:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Immunocytochemistry

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Adhesion Aids | Poly-D-lysine, Poly-L-lysine, Fibronectin | Promotes cell attachment to coverslips | Critical for poorly adherent cells; concentration and coating time affect performance [11] |

| Fixatives | 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA), Methanol, Acetone | Preserves cellular structure and antigen integrity | Choice affects epitope availability; PFA requires permeabilization, methanol does not [6] |

| Permeabilization Agents | Triton X-100, Tween-20, Saponin | Creates pores in membranes for antibody access | Triton X-100 is harsh, Tween-20 is mild; select based on target protein localization [11] |

| Blocking Agents | Normal Serum, BSA, Glycine | Reduces non-specific antibody binding | Serum should match secondary antibody host species; BSA is less species-specific [6] |

| Primary Antibodies | Monoclonal, Polyclonal, Recombinant | Specifically binds target protein | Validate for ICC; consider species, clonality, and concentration [12] |

| Secondary Antibodies | Species-specific, cross-adsorbed | Binds primary antibody and carries fluorophore | Must recognize host species of primary antibody; cross-adsorbed reduces background [11] |

| Fluorophores | Organic dyes (FITC, TRITC), Alexa Fluor series, Quantum Dots | Generates detectable signal | Consider brightness, photostability, and microscope compatibility [14] |

| Mounting Media | Anti-fade reagents with/without DAPI | Preserves samples and reduces photobleaching | Some include counterstains; hardening varieties don't require sealing [15] |

| Thrombin inhibitor 13 | Thrombin inhibitor 13, MF:C16H17ClN6OS, MW:376.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Antibacterial agent 166 | Antibacterial agent 166, MF:C11H8ClN3O4, MW:281.65 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Even with optimized protocols, researchers may encounter challenges that affect data quality. The following table addresses common issues and their solutions:

Table 4: Troubleshooting Common ICC Problems

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weak or No Staining | Insufficient antibody concentration; Inadequate permeabilization; Epitope masking | Increase primary antibody concentration; Optimize permeabilization; Try alternative fixatives | Validate antibodies for ICC; Include positive controls; Test multiple fixation methods [13] [12] |

| High Background | Excessive antibody concentration; Inadequate blocking; Non-specific secondary binding | Titrate antibodies; Increase blocking time; Use secondary antibody controls | Use cross-adsorbed secondary antibodies; Include no-primary controls; Optimize wash stringency [12] [15] |

| Non-specific Staining | Antibody cross-reactivity; Over-fixation; Endogenous fluorophores | Use pre-adsorbed antibodies; Reduce fixation time; Quench autofluorescence | Validate antibody specificity; Include isotype controls; Use quenching protocols [13] |

| Cell Loss from Coverslips | Harsh washing; Inadequate adhesion; Over-permeabilization | Gentle washing; Use coated coverslips; Optimize detergent concentration | Coat coverslips with poly-lysine; Avoid drying; Minimize mechanical disturbance [13] [15] |

| Photobleaching | Excessive light exposure; Inadequate anti-fade protection | Reduce exposure time; Use anti-fade mounting media | Store slides in dark; Use more photostable fluorophores; Image promptly [11] |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The fundamental principles of antibody and fluorophore interactions continue to enable increasingly sophisticated applications in cell biology research and drug development. Recent advances include:

Multiplexed Detection: Using multiple primary antibodies from different host species with spectrally distinct fluorophores enables simultaneous visualization of several proteins within the same cell, revealing functional relationships and protein interactions [6]. New fluorophores with narrow emission spectra, particularly quantum dots, are expanding multiplexing capabilities [14].

Live-Cell Imaging: Specialized techniques allow protein tracking in living cells using fluorescent protein tags or cell-permeable fluorescent dyes, enabling researchers to study protein dynamics in real time.

Super-Resolution Microscopy: Breaking the diffraction limit of light, techniques like STORM and STED microscopy provide unprecedented spatial resolution, revealing subcellular structures at the nanoscale level. These methods often require specialized fluorophores with specific photoswitching properties.

Automated Image Analysis: Artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches are revolutionizing how ICC data is analyzed, enabling high-content screening, automated cell segmentation, and quantitative analysis of protein localization and expression levels [16].

Nanoparticle Conjugates: Antibodies conjugated to specialized nanoparticles, such as gold nanoparticles and quantum dots, are expanding detection capabilities for both imaging and therapeutic applications [14] [17]. These conjugates offer enhanced brightness, photostability, and additional functionalities such as therapeutic payload delivery.

The continued refinement of antibody specificity, fluorophore performance, and detection methodologies ensures that immunocytochemistry will remain an essential tool for understanding cellular function and developing new therapeutic strategies in biomedical research.

Immunocytochemistry (ICC) is a foundational technique in cell biology research and drug development, enabling the visualization and localization of specific proteins or antigens within cultured cells using antibody-based staining and fluorescence detection. The power of this technique lies in its ability to provide high-resolution spatial information about protein expression and distribution within the cellular context, making it indispensable for understanding cellular mechanisms, disease pathology, and drug effects. For researchers and scientists working with cell cultures, mastering ICC requires not only procedural knowledge but also a deep understanding of the essential reagents that enable specific labeling and the specialized equipment necessary for detection and analysis. The critical importance of this methodology is reflected in its widespread adoption and continuous refinement within the scientific community, with leading antibody suppliers and research institutions providing detailed protocols to ensure reproducible and high-quality results [6] [18] [11].

This application note provides a comprehensive framework for implementing a robust immunocytochemistry protocol, detailing the necessary reagents, equipment, and step-by-step methodologies required for successful protein localization studies in fixed cells. By framing these technical elements within the broader context of cell culture research, we aim to equip researchers with the practical knowledge needed to obtain reliable, publication-quality data while troubleshooting common challenges encountered in the ICC workflow.

Experimental Workflow

The successful execution of an immunocytochemistry experiment follows a logical sequence of steps from sample preparation through final imaging. Each stage must be carefully optimized to preserve cellular architecture, maintain antigen integrity, and minimize non-specific background staining while maximizing specific signal detection.

The following workflow diagram outlines the critical path for a standard indirect immunocytochemistry protocol:

Diagram 1: ICC experimental workflow showing key procedural steps with typical time requirements.

Workflow Stage Details

Cell Seeding and Preparation: Cells are cultured on glass coverslips, often coated with adhesion-promoting substances like poly-L-lysine or poly-D-lysine to ensure proper attachment and spreading. Careful attention to cell density and viability (typically >90%) is essential for optimal results [6] [11].

Fixation: This critical step preserves cellular morphology and immobilizes antigens by cross-linking or precipitating cellular components. The choice of fixative depends on the antigen properties and experimental requirements, with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) being most common for protein epitope preservation [6] [18].

Permeabilization: For intracellular targets, particularly when using PFA fixation, permeabilization with detergents like Triton X-100 creates pores in the membrane, allowing antibodies to access internal structures. This step is unnecessary when using organic solvents like methanol as fixatives, as they simultaneously fix and permeabilize cells [6] [11].

Blocking: To prevent non-specific antibody binding, samples are incubated with protein-rich solutions such as bovine serum albumin (BSA) or serum from the host species of the secondary antibody. This crucial step significantly reduces background fluorescence [6] [18].

Antibody Incubation: The core detection phase involves sequential incubation with primary antibodies specific to the target antigen, followed by fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies that recognize the primary antibody host species. Optimal antibody concentrations and incubation times must be determined empirically for each target [18] [11].

Mounting and Imaging: After staining, samples are mounted with anti-fade medium, often containing DNA counterstains like DAPI, and sealed for preservation. Imaging is performed using fluorescence microscopy with appropriate filter sets for each fluorophore [18] [11].

Research Reagent Solutions

A successful immunocytochemistry experiment requires careful selection and optimization of reagents at each stage of the protocol. The table below details the essential reagents, their specific functions, and considerations for their use in the ICC workflow.

Table 1: Essential reagents for immunocytochemistry protocols

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Usage Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixatives | 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) [6] [18] [11] | Preserves cellular structure and immobilizes antigens | 10-20 min at room temperature; requires permeabilization for intracellular targets |

| Cold Methanol (-20°C) [6] [18] [11] | Precipitates proteins; simultaneously fixes and permeabilizes | 5-10 min at -20°C; no additional permeabilization needed | |

| Cold Acetone (-20°C) [6] | Excellent for cytoskeletal preservation | 5-10 min at -20°C; can make cells brittle | |

| Permeabilization Agents | Triton X-100 (0.1-0.5%) [6] [18] [11] | Non-ionic detergent that solubilizes membranes | 0.1-0.2% for 2-5 min; may disrupt some membrane proteins |

| Tween-20 (0.1-0.5%) [6] [11] | Milder detergent alternative | Better for preserving membrane protein epitopes | |

| Saponin (0.1-0.5%) [6] [11] | Cholesterol-binding detergent; creates reversible pores | Preferred for membrane-associated antigens | |

| Blocking Agents | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA; 1-5%) [6] [18] [11] | Non-specific protein blocker | Compatible with most antibodies; less species-specific |

| Normal Serum (1-5%) [6] [18] [11] | Serum from secondary antibody host species | Highly effective; must match secondary antibody host | |

| Detection Reagents | Primary Antibodies [18] [11] | Binds specifically to target antigen | Must be validated for ICC; concentration typically 5-20 µg/mL |

| Fluorophore-conjugated Secondary Antibodies [18] [11] | Binds primary antibody; provides fluorescence signal | Must target host species of primary antibody; typically used at 1:500-1:1000 dilution | |

| DAPI (1 µg/mL) [18] [11] | DNA intercalating dye; nuclear counterstain | 5 min incubation; compatible with most fluorophores |

Reagent Selection and Optimization

The choice of specific reagents within each category significantly impacts ICC results. Fixative selection represents a critical decision point: cross-linking fixatives like PFA provide superior morphological preservation but may mask some epitopes, while precipitating fixatives like methanol can better preserve some antigenic sites but may disrupt cellular structures [6]. For researchers studying phosphorylated proteins, all buffers should include protein phosphatase inhibitors according to manufacturer's instructions to maintain phosphorylation states during processing [11].

Blocking agent selection depends on the detection strategy. When using secondary antibodies, normal serum from the same species as the secondary antibody provides the most effective blocking, while BSA offers a compatible alternative with less species specificity [6]. Blocking solutions typically also include low concentrations of detergents (0.1-0.3% Triton X-100) to further reduce non-specific binding throughout the antibody incubation steps [11].

Essential Equipment

The transition from experimental preparation to detection and analysis requires specialized instrumentation designed to handle the unique demands of fluorescence-based cellular imaging. The equipment portfolio for immunocytochemistry spans from basic cell culture needs to advanced imaging platforms.

Table 2: Essential equipment for immunocytochemistry and fluorescence microscopy

| Equipment Category | Specific Examples | Key Applications in ICC | Performance Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Systems | COâ‚‚ Incubators [6] [18] | Maintain optimal pH, temperature, and humidity for cell growth | Stability and uniformity of temperature and COâ‚‚ critical |

| Biological Safety Cabinets [6] [18] | Provide sterile environment for cell culture procedures | Proper airflow and certification essential for contamination control | |

| Sample Preparation Equipment | Centrifuges [6] | Pellet cells for processing; ~200 × g for 5 minutes | Refrigerated models preferred for temperature-sensitive protocols |

| Aspiration/Vacuum Systems [18] [11] | Gentle removal of solutions without disturbing cells | Precision control to avoid damaging cell monolayers | |

| Microscopy Systems | Widefield Fluorescence Microscopes [6] [18] | Standard imaging of fluorescently labeled samples | Filter sets must match fluorophore excitation/emission spectra |

| Confocal Microscopes | Optical sectioning to reduce out-of-focus light | Enhanced resolution and signal-to-noise for 3D reconstruction | |

| Spectral Imaging Systems [19] | Unmixing overlapping fluorophores | Enable higher multiplexing with minimal spectral spillover | |

| Detection and Analysis Instruments | Flow Cytometers [19] | Quantitative analysis of cell populations | High-parameter systems (e.g., spectral) enable complex panels |

| High-Content Imaging Systems | Automated acquisition and analysis of cell phenotypes | Ideal for screening applications and quantitative cell biology | |

| Specialized Accessories | Humidified Chambers [11] | Prevent evaporation during antibody incubations | Critical for overnight incubations to maintain sample integrity |

| Coverslips (#1.5 thickness) [18] [11] | Optimal for high-resolution oil immersion objectives | Must match microscope objective specifications |

Equipment Selection Criteria

Choosing appropriate equipment requires careful consideration of experimental goals and technical requirements. For standard immunofluorescence applications, a widefield epifluorescence microscope equipped with high-quality objectives and appropriate filter sets typically suffices. However, for experiments requiring precise optical sectioning, reduced background, or three-dimensional reconstruction, laser scanning confocal microscopy provides significant advantages despite higher complexity and cost.

The growing field of high-content screening has driven development of automated imaging systems that combine fluorescence microscopy with automated sample handling and sophisticated image analysis algorithms. These systems enable quantitative analysis of thousands of cells across multiple parameters, providing statistical power for drug discovery and systems biology applications [20].

Recent technological advances have also improved flow cytometry capabilities, with spectral flow cytometry emerging as a powerful alternative to conventional flow cytometry. These systems use full spectrum detection and computational unmixing to resolve fluorescent labels with overlapping emission spectra, enabling higher-parameter experiments without compensation challenges [19]. The global flow cytometry market reflects these advancements, projected to grow from $5.2 billion in 2023 to $8.3 billion by 2029, driven by increasing demand for advanced cell analysis solutions in research and clinical applications [20].

Detailed Protocols

Standard Immunocytochemistry Protocol

This protocol outlines the complete procedure for indirect immunofluorescence staining of adherent cells cultured on glass coverslips, including critical steps for fixation, permeabilization, blocking, and antibody incubation.

Materials Required:

- Sterile glass coverslips (#1.5 thickness)

- Poly-L-lysine or poly-D-lysine coating solution

- Cell culture medium and PBS

- Fixative (4% PFA in PBS or cold methanol)

- Permeabilization solution (0.1-0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS)

- Blocking solution (1-5% BSA or normal serum in PBS)

- Primary antibody specific to target antigen

- Fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody

- DAPI solution (1 µg/mL in PBS)

- Antifade mounting medium

- Microscope slides and nail polish

Procedure:

Coverslip Preparation and Cell Seeding

- Place sterile coverslips in tissue culture plates and coat with poly-L-lysine solution for 1 hour at room temperature [6].

- Rinse coated coverslips three times with sterile PBS and allow to dry completely [6].

- Seed cells at appropriate density (dependent on cell type and experimental requirements) and culture until 60-80% confluent [18] [11].

Fixation

- Aspirate culture medium and gently wash cells three times with PBS at room temperature [18] [11].

- Fix cells with freshly prepared 4% PFA for 10-20 minutes at room temperature [6] [18].

- Alternatively, for methanol fixation, incubate with chilled (-20°C) 100% methanol for 5-10 minutes at room temperature [6] [11].

- Wash fixed cells three times with PBS for 5 minutes each [18].

Permeabilization (if using PFA fixation)

Blocking

Primary Antibody Incubation

- Prepare primary antibody dilution in blocking solution (typical range 5-20 µg/mL) [18].

- Incubate cells with primary antibody solution for 1 hour at room temperature or overnight at 4°C in a humidified chamber [18] [11].

- Wash cells three times with PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 minutes each [11].

Secondary Antibody Incubation

- Prepare fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody dilution in blocking solution (typically 1:500 to 1:1000) [11].

- Incubate cells with secondary antibody solution for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark [18] [11].

- Wash cells three times with PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 minutes each [11].

Counterstaining and Mounting

- Incubate cells with DAPI solution (1 µg/mL) for 5 minutes at room temperature [18] [11].

- Rinse briefly with PBS to remove excess DAPI [18].

- Place a drop of antifade mounting medium on a clean microscope slide [18] [11].

- Carefully invert coverslip (cell side down) onto mounting medium, avoiding air bubbles [18].

- Seal coverslip edges with clear nail polish if required by mounting medium [18] [11].

- Store slides flat in the dark at 4°C until imaging [11].

Imaging

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Even with careful execution, ICC experiments can encounter challenges that affect result quality. The following diagram illustrates a systematic approach to diagnosing and resolving common problems in immunocytochemistry:

Diagram 2: ICC troubleshooting guide showing common problems and their solutions.

Specific Troubleshooting Recommendations:

Excessive Background Fluorescence: Increase blocking time to 2 hours or use higher concentration (5-10%) of blocking agent [6] [18]. Include 0.1M glycine in blocking buffer to quench free aldehyde groups from PFA fixation [6]. Increase number and duration of washes after antibody incubations, and titrate antibody concentrations to optimal levels [18].

Weak or No Specific Signal: Verify antibody specificity and confirm it is validated for ICC. Test a range of primary antibody concentrations (5-20 µg/mL) and consider longer incubation times (overnight at 4°C) [18] [11]. Ensure fluorophore is compatible with microscope filter sets and check for photobleaching during processing.

Poor Cellular Morphology: Optimize fixation conditions - reduce PFA concentration or fixation time if over-fixed, or increase if under-fixed [6]. For delicate structures, consider alternative fixatives like methanol or acetone at -20°C [6] [11]. Always handle coverslips gently and avoid allowing cells to dry out during processing [18].

Non-specific Staining Patterns: Include appropriate negative controls (no primary antibody, isotype control) to distinguish specific from non-specific signal. For double-labeling experiments, ensure primary antibodies are from different host species to prevent cross-reactivity of secondary antibodies [6] [11].

Within the framework of immunocytochemistry (ICC) research, the foundation for a successful experiment is laid long before the first antibody is applied. The preparation of cell cultures, specifically the coating of coverslips and the subsequent seeding of cells, is a critical initial step that directly influences cell health, morphology, and the ultimate clarity and specificity of fluorescent imaging. Proper adhesion ensures that cells remain securely attached throughout the rigorous processes of fixation, permeabilization, and multiple washing steps, thereby preserving the structural integrity required for accurate protein localization studies. This application note provides a detailed, practical guide to these essential preparatory phases, equipping researchers with the methodologies to achieve robust and reproducible results in their cell-based assays.

Coating Coverslips for Enhanced Cell Adhesion

Many cultured cell types, particularly those grown on glass coverslips, require a coating substrate to promote adequate adhesion. An untreated glass surface often does not provide the necessary biological cues for cells to attach and spread effectively. Applying a thin layer of a coating material mimics the extracellular matrix, providing a scaffold that facilitates strong cell attachment.

Coating Material Selection and Preparation

The choice of coating material depends on the specific cell type and research application. The table below summarizes common coating solutions and their typical uses.

Table 1: Common Coverslip Coating Solutions and Protocols

| Coating Solution | Common Concentrations | Incubation Time | Incubation Temperature | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gelatin [9] | 0.1% in deionized Hâ‚‚O | 10 minutes | Room Temperature | Enhances adhesion for many standard cell lines. Simple and cost-effective. |

| Poly-L-Lysine (PLL) [6] | Varies by manufacturer | 1 hour to 24 hours | Room Temperature | Provides a positive charge for strong cell attachment. Suitable for neurons and other fastidious cells. |

| Poly-D-Lysine (PDL) [11] | Varies by manufacturer | 1 hour | Room Temperature | Similar to PLL but more resistant to cellular proteases. |

| Fibronectin [11] | 1-10 µg/mL | 1-2 hours | 37°C | A natural extracellular matrix protein; ideal for studies involving cell migration and differentiation. |

Step-by-Step Coating Protocol

The following generalized protocol, adaptable for the solutions in Table 1, is designed for sterilized glass coverslips placed in a multi-well plate [9] [6].

- Placement: Using fine tweezers, place sterilized coverslips into the wells of a tissue culture plate (e.g., a 24-well plate).

- Application: Add enough coating solution to completely cover the coverslip (e.g., 400 µL for a 24-well plate) [9].

- Incubation: Incubate for the recommended time and temperature (see Table 1).

- Rinsing: After incubation, carefully aspirate or pour off the coating solution. Rinse the coverslips three times with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove any unbound coating material [6].

- Drying: Allow the rinsed coverslips to air-dry completely inside the sterile tissue culture hood. Dried coverslips can be stored at room temperature until ready for use [9]. For long-term storage, ensure the plate is sealed to maintain sterility.

Seeding Cells onto Coated Coverslips

Once the coverslips are prepared, cells are seeded onto them. The goal is to achieve an appropriate density and distribution for the specific experimental aims, typically semi-confluency to confluency by the time of fixation.

Cell Seeding Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the logical sequence from coating to the point of fixation for ICC.

Detailed Seeding and Culture Protocol

- Harvest and Count Cells: Gently harvest cells using standard trypsinization or non-enzymatic methods. Determine the total cell number and concentration. A cell viability of 90–95% is generally recommended for optimal results [6].

- Prepare Cell Suspension: Dilute the cell stock to the desired concentration in pre-warmed, complete culture medium. The appropriate density is highly dependent on the cell type and its growth rate, as well as the desired confluence at the time of fixation. A typical starting point for a 24-well plate is 5000 - 50,000 cells in 500 µL of medium per well [9] [6].

- Seed Cells: Gently add the cell suspension to the well, aiming for the center of the coated coverslip. Avoid dropping the solution directly onto the coverslip with force, as this can displace the coating or create uneven cell distribution [21].

- Distribute Cells: To ensure an even distribution of cells across the coverslip, gently rock the plate back and forth and side-to-side.

- Incubate: Carefully transfer the culture plate to a 37°C, 5% CO₂ incubator. Allow the cells to adhere and grow until they reach the desired density or age for the experiment. This typically ranges from semi-confluency to full confluency [21] [11].

- Treat (Optional): If the experimental design requires it, administer drug treatments or other stimuli to the cells according to your specific protocol.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Coverslip Preparation and Cell Seeding

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Glass Coverslips (#1.5) [11] | Optimal thickness for high-resolution fluorescence microscopy. |

| Gelatin, Poly-L-Lysine, Fibronectin [9] [6] [11] | Coating substrates to promote cell adhesion to glass surfaces. |

| Sterile PBS [9] [6] | For rinsing coated coverslips and washing cells; maintains a physiologically compatible pH and osmolarity. |

| Tissue Culture Plates (e.g., 24-well) [9] | Provides a sterile, multi-well format for processing multiple coverslips simultaneously. |

| Fine Tweezers [9] [21] | For the careful handling of sterile coverslips without damage. |

| Cell Culture Medium [9] | Provides essential nutrients for cell health and growth after seeding. |

| Serum (e.g., FBS) | A common supplement to culture medium that contains adhesion factors and growth promoters. |

| Hemocytometer or Automated Cell Counter | For accurate determination of cell concentration and viability prior to seeding. |

| 2-Fluoro-1,3-bis(methyl)benzene-d6 | 2-Fluoro-1,3-bis(methyl)benzene-d6, MF:C8H9F, MW:130.19 g/mol |

| Telomeric G4s ligand 1 | Telomeric G4s ligand 1, MF:C31H37F3N6, MW:550.7 g/mol |

Troubleshooting and Key Considerations for Optimal Adherence

- Insufficient Adhesion: If cells detach during washes, consider testing a different or more concentrated coating agent. Ensure the coating solution is properly prepared and the coverslips are rinsed thoroughly to prevent a toxic or non-adhesive residue. Verify that the cell viability at seeding is high [6] [21].

- Optimization is Critical: The optimal coating material, cell seeding density, and growth time are empirically determined. Researchers should consult the literature for their specific cell type and be prepared to optimize these parameters.

- Gentle Handling: Throughout the process, treat the coverslips and cells gently. Never let the coverslips dry out after seeding, and always pipet solutions against the side of the well, not directly onto the cells [21].

Meticulous preparation of coverslips and careful cell seeding are non-negotiable prerequisites for high-quality immunocytochemistry. By selecting an appropriate coating substrate, following a sterile and consistent coating protocol, and seeding cells at an optimal density, researchers can ensure strong cell adherence and preservation of native morphology. This foundational work directly contributes to the generation of reliable, high-resolution imaging data, forming the cornerstone of valid and impactful scientific conclusions in cell biology and drug development research.

Step-by-Step ICC Protocol: Fixation, Staining, and Imaging for Cultured Cells

Cell Fixation: Comparing Paraformaldehyde, Methanol, and Acetone for Morphology and Antigen Preservation

In immunocytochemistry (ICC) research, fixation is a critical first step that profoundly influences all subsequent results. This process aims to preserve cellular morphology and maintain the antigenicity of target molecules, providing a "snapshot" of the cell's state [22]. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate fixative represents a fundamental compromise between structural preservation and epitope accessibility. The choice is not trivial, as incomplete fixation can permit proteolytic degradation of targets, while excessive fixation may mask epitopes or create strong non-specific background staining [23].

This application note systematically compares three widely used fixatives—paraformaldehyde, methanol, and acetone—within the context of optimizing immunocytochemistry protocols for cell culture research. We provide a detailed comparative analysis based on empirical evidence, alongside standardized protocols to ensure experimental reproducibility and reliability in both basic research and drug development applications.

Mechanism of Action and Cellular Effects

Understanding how each fixative operates at the molecular level is crucial for predicting its effects on cellular components and selecting the most appropriate agent for specific research goals.

Paraformaldehyde (PFA) is a cross-linking fixative that creates covalent methylene bridges (-CHâ‚‚-) between protein-protein and protein-nucleic acid groups, primarily involving the residues of the basic amino acid lysine [24] [23]. This cross-linking network effectively stabilizes soluble proteins by anchoring them to the cytoskeleton, preserving cellular ultrastructure with high fidelity [25] [24]. However, this same mechanism can potentially mask antigenic epitopes through chemical modification or steric hindrance, sometimes necessitating antigen retrieval techniques to restore antibody binding [23].

Methanol and Acetone are both precipitating fixatives that operate through dehydration and protein precipitation. They act by displacing water molecules in tissues, disrupting hydrogen bonds, and causing proteins to denature and precipitate in-situ [24] [22]. This precipitation mechanism generally does not mask epitopes but can significantly alter protein conformation and tertiary structure through hydrophobic bond breakage [23]. A critical distinction is that both solvents simultaneously fix and permeabilize cells in a single step, eliminating the need for separate permeabilization protocols when used alone [6] [26].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental mechanisms through which each fixative type stabilizes cellular components:

Visualization of cellular structures reveals profound differences between these mechanisms. Studies utilizing reflection contrast and electron microscopy demonstrate that acetone or methanol fixation alone results in complete loss of integrity of intracellular structures and poor preservation of plasma membrane integrity [27]. In contrast, aldehyde-based fixatives like paraformaldehyde show significantly superior preservation of both intracellular and plasma membranes [27] [25].

Comparative Analysis of Fixative Performance

The choice between paraformaldehyde, methanol, and acetone involves trade-offs between morphological preservation, antigen accessibility, and practical handling considerations. The table below summarizes key performance characteristics based on empirical studies:

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Fixative Properties and Performance

| Parameter | Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Methanol | Acetone |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of Action | Cross-linking via methylene bridges [23] | Protein precipitation & dehydration [24] [22] | Protein precipitation & dehydration [22] [26] |

| Morphology Preservation | Excellent [27] [25] | Moderate to Poor [27] [22] | Poor [22] [26] |

| Membrane Integrity | Well-preserved [27] | Poorly preserved [27] | Poorly preserved [22] |

| Antigen Masking | Moderate to High (due to cross-linking) [23] | Low [22] [26] | Low [22] [26] |

| Permeabilization | Required as separate step [6] | Simultaneous with fixation [6] | Simultaneous with fixation [26] |

| Typical Concentration | 2-4% in PBS [28] [6] | 95-100% (chilled) [6] | 100% (chilled) [6] |

| Fixation Time | 10-20 min at RT [28] [6] | 5-10 min at -20°C [6] | 5-10 min at -20°C [6] |

| Compatible Applications | Standard ICC/IHC, EM, multiplex staining [28] [25] | scRNA-seq, microtubule staining [29] [26] | Frozen sections, nuclear antigens [22] [26] |

| Impact on Fluorescent Proteins | Moderate (can be preserved with mild fixation) | High (often denatured) [22] | High (often denatured) [22] |

| RNA Preservation | Moderate (for crosslinking-based protocols) [24] | Excellent (for scRNA-seq) [29] [24] | Not typically used for RNA work |

| Storage After Fixation | Stable in azide/PBS for 1-2 weeks at 4°C [6] | Long-term at -80°C possible [29] | Immediate processing recommended |

The structural consequences of these differences are significant. Aldehyde fixatives like PFA show an altered biochemical content attributed to adduct formation, but this can be minimized by optimizing fixation temperature or through detergent-based permeabilization treatments [25]. Organic solvents, in contrast, lead to a severe loss of cell content attributed to the loss of membrane integrity after lipid removal [25]. For researchers focusing on membrane proteins, this represents a critical consideration, as alcohol-based fixatives may compromise the detection of these targets [22].

Application-Specific Recommendations

Optimal Fixative Selection by Research Goal

The appropriate fixative choice depends heavily on the primary research objective, whether it's ultrastructural analysis, antigen detection, or specific molecular profiling. The following decision pathway provides a systematic approach to selection:

Specialized Applications

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing: Recent systematic comparisons demonstrate that methanol fixation provides a compelling option for droplet-based single-cell transcriptomics of neural cells [29]. Methanol-fixed samples display cellular composition similar to fresh samples with good cell quality and minimal expression biases [29]. While DMSO cryopreservation provides higher library complexity in terms of RNA molecules and genes detected per cell, it strongly affects cellular composition and induces stress and apoptosis gene expression [29]. For sequencing applications, methanol fixation largely preserves RNA integrity, enabling high-quality cDNA synthesis without severe degradation [24].

Membrane and Lipid-Associated Targets: For experiments focusing on membrane proteins or lipid domains, PFA is generally preferable as it better preserves membrane integrity [22] [23]. Alcohol-based fixatives dissolve membranes during the fixation process, potentially compromising the detection of membrane-associated antigens [22].

Fluorescent Protein Detection: When detecting endogenously expressed fluorescent proteins (e.g., GFP), PFA is strongly recommended as alcohol-based fixatives typically denature these proteins, resulting in loss of signal [22].

Standardized Experimental Protocols

Paraformaldehyde Fixation Protocol for ICC

This protocol is suitable for most immunocytochemistry applications requiring optimal morphological preservation [28] [6].

Materials Required:

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4

- Fixation solution: 4% formaldehyde/PFA in PBS (with 4% sucrose optional)

- Permeabilization solution: 0.1-0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS

- Blocking buffer: 2-10% normal serum or BSA in PBS

Procedure:

- Culture cells on appropriately coated coverslips or multi-well plates until desired confluence is reached.

- Wash cells briefly with room temperature PBS to remove culture medium and serum components.

- Fix cells with 4% PFA solution for 10-20 minutes at room temperature [28] [6].

- Wash three times with PBS for 5 minutes each to thoroughly remove residual fixative.

- Permeabilize with 0.1-0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 2-5 minutes at room temperature (optional for membrane antigens) [6].

- Wash three times with PBS for 5 minutes each.

- Proceed with blocking and antibody incubation steps.

Technical Notes: For sensitive antigens, reduce fixation time to 10 minutes or consider lower PFA concentrations (2%). For thick structures, extend fixation time up to 30 minutes. Fixed samples can be stored in PBS with 0.1% sodium azide at 4°C for 1-2 weeks [6].

Methanol Fixation Protocol for ICC

This protocol is recommended for intracellular antigens sensitive to cross-linking or for specific applications like microtubule visualization [6] [26].

Materials Required:

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4

- Methanol (95-100%), pre-chilled to -20°C

- Blocking buffer: 2-10% normal serum or BSA in PBS

Procedure:

- Culture cells on appropriately coated coverslips or multi-well plates.

- Remove culture medium and briefly rinse with PBS.

- Fix cells with ice-cold methanol (-20°C) for 5-10 minutes at -20°C [6].

- Remove methanol and wash three times with PBS for 5 minutes each.

- Rehydrate and block with appropriate blocking buffer for 1-2 hours.

- Proceed directly with antibody incubation (no separate permeabilization required).

Technical Notes: Methanol fixation is typically performed at -20°C to slow the fixation rate and improve lipid preservation [26]. The fixed samples can be stored in PBS at 4°C for short periods or at -80°C for long-term preservation [29].

Acetone Fixation Protocol for ICC

This protocol is suitable for frozen sections, nuclear antigens, or when maximum epitope exposure is critical [6] [26].

Materials Required:

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4

- Acetone (100%), pre-chilled to -20°C

- Blocking buffer: 2-10% normal serum or BSA in PBS

Procedure:

- Culture cells on appropriately coated coverslips or multi-well plates.

- Remove culture medium and briefly rinse with PBS.

- Fix cells with ice-cold acetone (-20°C) for 5-10 minutes at -20°C [6].

- Air dry cells briefly (30-60 seconds) to allow acetone evaporation.

- Rehydrate with PBS for 5-10 minutes.

- Block with appropriate blocking buffer for 1-2 hours.

- Proceed with antibody incubation (no separate permeabilization required).

Technical Notes: Acetone fixation is particularly harsh and can extract significant cellular components, but it provides excellent epitope exposure for certain antigens [26]. Avoid extended fixation times as they may increase cellular damage.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Immunocytochemistry

| Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Paraformaldehyde (4% in PBS) | Cross-linking fixative that preserves cellular structure | Ideal for most ICC applications; may require antigen retrieval for some epitopes [28] [23] |

| Methanol (100%, chilled) | Precipitating fixative and permeabilizing agent | Use for epitopes sensitive to cross-linking; denatures fluorescent proteins [6] [22] |

| Acetone (100%, chilled) | Strong dehydrating fixative and permeabilizing agent | Excellent for nuclear antigens and frozen sections; very harsh on morphology [22] [26] |

| Triton X-100 (0.1-0.5%) | Non-ionic detergent for membrane permeabilization | Required after PFA fixation; use milder concentrations (0.1%) for membrane proteins [6] |

| Tween-20 (0.1-0.5%) | Mild non-ionic detergent for permeabilization | Alternative to Triton X-100; less disruptive to membrane structures [6] |

| Normal Serum (2-10%) | Blocking agent to reduce non-specific binding | Use serum from secondary antibody host species for optimal blocking [28] [6] |

| BSA (1-5%) | Protein-based blocking agent | Less species-specific than serum; compatible with wide antibody range [6] |

| Glycine (0.1 M) | Quenching agent for aldehyde groups | Neutralizes unreacted aldehyde groups after PFA fixation to reduce background [6] |

| SARS-CoV-2 Mpro-IN-19 | SARS-CoV-2 Mpro-IN-19, MF:C29H33N3O5, MW:503.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Megovalicin H | Megovalicin H, MF:C35H63NO7, MW:609.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The selection of an appropriate fixative represents a critical decision point in immunocytochemistry experimental design that directly influences data quality and interpretability. Paraformaldehyde excels in morphological preservation and is the preferred choice for most general applications, membrane protein detection, and fluorescent protein preservation. Methanol offers distinct advantages for specific applications including single-cell RNA sequencing, detection of cross-linking-sensitive epitopes, and microtubule visualization. Acetone, while harsh on cellular structure, provides excellent epitope exposure for challenging nuclear antigens and frozen sections.

A comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms, trade-offs, and optimized protocols for each fixative type enables researchers to make informed decisions that align with their specific research objectives. By standardizing fixation protocols according to these evidence-based guidelines, the reliability and reproducibility of immunocytochemistry research in both basic science and drug development contexts can be significantly enhanced.

Permeabilization is a critical laboratory technique in immunocytochemistry (ICC) used to create pores in the cell membrane, allowing antibodies to access intracellular targets. This process is essential after using cross-linking fixatives like paraformaldehyde (PFA), which preserve cell structure but leave the membrane intact and impermeable to antibodies. Without effective permeabilization, antibodies cannot reach their intracellular antigens, resulting in false-negative results or weak staining. The selection of appropriate permeabilization agents and protocols directly impacts experimental outcomes, making it crucial for researchers to understand the mechanisms, advantages, and limitations of different permeabilization strategies.

The fundamental principle behind permeabilization involves the disruption of lipid bilayers through chemical agents that solubilize membrane components. These agents work through different mechanisms: some dissolve lipids organically, while others interact with specific membrane components like cholesterol to create temporary pores. The choice of permeabilization method depends on multiple factors, including the subcellular localization of the target antigen, the need to preserve other cellular structures, and compatibility with downstream detection methods. As research in cell biology advances, the strategic selection of permeabilization protocols has become increasingly important for accurate visualization of intracellular protein distribution, localization, and interactions.

Mechanism of Action of Common Permeabilization Detergents

Chemical Properties and Mechanisms

Permeabilization detergents function through distinct biochemical mechanisms that determine their applications and limitations in immunocytochemistry. Triton X-100, a non-ionic detergent, operates by inserting detergent monomers into the lipid membrane, ultimately solubilizing both lipids and proteins in a non-selective manner. This action creates pores in all cellular membranes, including the nuclear envelope, providing access to antigens throughout the cell. Its non-selective nature makes it highly effective for many intracellular targets but can damage membrane-associated antigens and alter cell morphology if used at high concentrations or for extended periods [30] [31].

In contrast, saponin functions through a more selective mechanism by interacting with membrane cholesterol to form porous complexes. Unlike Triton X-100, saponin does not solubilize membrane proteins and creates reversible pores that can reseal if saponin is removed from the buffer. This reversible action requires researchers to maintain saponin in all subsequent wash and antibody incubation buffers following permeabilization. Additionally, saponin typically does not permeabilize the nuclear membrane effectively, making it less suitable for nuclear targets without additional processing steps [31] [32].

Tween-20, another non-ionic detergent, shares similarities with Triton X-100 but is considered a milder alternative. While it also permeabilizes membranes through non-selective interaction with lipids and proteins, it has a more renaturing effect on proteins that might improve antibody-antigen binding in some cases. However, like Triton X-100, it can extract proteins along with lipids and may not be ideal for preserving membrane-associated antigens [30] [31].

Comparative Analysis of Detergent Properties

Table 1: Comparison of Key Permeabilization Detergents and Their Properties

| Detergent | Mechanism of Action | Membrane Selectivity | Nuclear Membrane Permeabilization | Reversibility | Impact on Protein Antigens |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triton X-100 | Inserts monomers into lipid membrane; solubilizes lipids and proteins | Non-selective | Yes | Irreversible | May extract or denature membrane proteins |

| Saponin | Interacts with cholesterol to form pores | Selective for cholesterol-rich membranes | No | Reversible | Preserves membrane protein integrity |

| Tween-20 | Solubilizes lipids and proteins through non-ionic interactions | Non-selective | Yes | Irreversible | Has renaturing effect; may preserve some epitopes |

Strategic Selection of Permeabilization Agents

Target-Specific Considerations

The subcellular localization of the target antigen is the primary consideration when selecting a permeabilization agent. For intracellular soluble proteins in the cytoplasm, Triton X-100 at concentrations of 0.1-0.2% with incubation times of 2-5 minutes is generally effective [6]. For cytoskeletal targets such as tubulin or actin, methanol fixation and permeabilization often yield superior results, as demonstrated by the improved performance of Keratin 8/18 and ß-Actin antibodies with methanol permeabilization compared to Triton X-100 [33].

When studying membrane-associated proteins, particularly cell surface receptors, careful consideration is required. Research has demonstrated that Triton X-100 can disrupt cell surface receptors, leading to false observations. A study on Notch 1 surface receptor found that cells treated with Triton X-100 gave false protein expression due to disruption of the cellular membrane, while cells without surfactant treatment exhibited fluorescence proportional to the true presence of Notch 1 receptors [34]. In such cases, saponin is the preferred choice as it better preserves membrane protein integrity.

For nuclear antigens, stronger permeabilization agents like Triton X-100 or Tween-20 are typically necessary as saponin does not effectively permeabilize the nuclear membrane [31]. When working with phosphorylated epitopes or other post-translational modifications, crosslinking fixatives like PFA followed by Triton X-100 permeabilization are generally recommended over alcohol-based methods, which can destroy these sensitive epitopes [33] [32].

Application-Based Selection Criteria

Table 2: Permeabilization Agent Selection Guide Based on Experimental Requirements

| Experimental Requirement | Recommended Agent | Concentration | Incubation Time | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General intracellular staining | Triton X-100 | 0.1-0.2% in PBS | 2-5 min at room temperature | Optimal balance of effectiveness and preservation [6] |

| Membrane-associated proteins | Saponin | 0.1-0.5% in PBS | 10 min at room temperature | Preserves membrane integrity; must include in all buffers [31] [32] |

| Nuclear antigens | Triton X-100 or Tween-20 | 0.1-0.3% in PBS | 5-10 min at room temperature | Required for nuclear membrane penetration [31] |

| Flow cytometry with surface markers | Saponin | 0.1% in PBS with BSA | 10 min at room temperature | Preserves surface epitopes and light scatter properties [32] |

| Phospho-epitope detection | Triton X-100 (after PFA) | 0.1-0.3% in PBS | 10 min at room temperature | Crosslinking fixatives preserve modification states [33] |

Workflow for Permeabilization Strategy Selection

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process for selecting an appropriate permeabilization strategy based on experimental requirements:

Detailed Experimental Protocols