Essential IHC Controls: A Comprehensive Guide to Positive and Negative Controls for Reliable Results

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a complete framework for implementing and validating controls in Immunohistochemistry (IHC) experiments.

Essential IHC Controls: A Comprehensive Guide to Positive and Negative Controls for Reliable Results

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a complete framework for implementing and validating controls in Immunohistochemistry (IHC) experiments. Covering foundational principles, practical methodologies, advanced troubleshooting, and contemporary validation standards, the guide synthesizes current best practices and guidelines, including the latest 2024 CAP update. It is designed to help professionals across both research and clinical settings ensure the specificity, sensitivity, and reproducibility of their IHC data, thereby enhancing the reliability of diagnostic and research outcomes.

The Critical Role of IHC Controls: Ensuring Specificity and Accuracy

Why Controls are Non-Negotiable in IHC Experiments

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) stands as a cornerstone technique in biomedical research and clinical diagnostics, enabling the visualization of specific protein markers within their proper tissue context. However, the validity of interpretations derived from IHC hinges entirely on the implementation of appropriate controls. Despite their critical importance, evidence indicates that up to 80% of published papers omit descriptions of essential controls, potentially leading to irreproducible findings and erroneous scientific conclusions. This comprehensive guide examines the fundamental role of positive and negative controls in IHC experiments, providing researchers with detailed methodologies, validation frameworks, and standardized practices to ensure assay specificity, sensitivity, and reliability.

The Critical Role of Controls in IHC

Immunohistochemistry is no different from any other experimental technique: the quality of the results relies entirely on the analyte, reagents, precise experimental technique, correct application of controls, and accurate interpretation of the data [1]. Simply stated, an immunohistochemical assay that lacks controls cannot be validly interpreted [1]. The absence of proper controls threatens the very foundation of scientific investigation by permitting inaccurate interpretations that can lead to wasted resources, irreproducible results, and erosion of confidence in research findings.

Alarming evidence from an informal survey of 100 articles across nine high-impact journals revealed that up to 80% of papers incorporating IHC data do not mention controls, and 89% of author guidelines for these journals do not require or even mention controls [1]. This oversight at both the research and publication levels underscores a systemic undervaluing of appropriate controls, despite their fundamental importance in validating experimental outcomes. Proper controls are essential to distinguish specific signal from non-specific background, verify reagent performance, and confirm technical execution throughout the complex IHC workflow.

Classification and Implementation of IHC Controls

Positive Controls: Validating Assay Performance

Positive controls are specimens known to express the target antigen in a specific location and pattern, serving to demonstrate that the staining protocol is successfully performed and providing the expected level of sensitivity and specificity as characterized during technical optimization [2] [3].

Types of Positive Controls:

- Anatomical Positive Controls: Utilize tissue with known expression of the target protein, where the presence and location of the antigen have been previously established through other experimental evidence [1].

- Internal Positive Controls: Leverage known sites of target expression within the experimental specimen itself, providing inherent validation without requiring separate tissue sections [1].

- External Positive Controls: Employ separate specimens or slides confirmed to contain the molecule targeted by the antibody, run in parallel with experimental samples [1].

The most rigorous positive control is the positive anatomical control, where the presence of the antigen in the specimen is known a priori and is not the target of the experimental treatment [1]. For example, an assay using an antibody specific for insulin should include sections of pancreas containing islets of Langerhans, with the antibody selectively visualizing only the insulin-producing beta cells [1].

Negative Controls: Establishing Specificity

Negative controls demonstrate that the observed staining results specifically from interaction between the target epitope and the antibody's paratope, rather than non-specific interactions or technical artifacts [1]. These controls are known not to express the target antigen and are essential for checking non-specific signals and false-positive results [2].

Critical Negative Control Modalities:

Table 1: Essential Negative Controls for IHC Validation

| Control Type | Composition | Purpose | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Primary Antibody Control | Tissue section incubated with antibody diluent alone, followed by secondary antibodies and detection reagents [2] | Verifies staining is produced by primary antibody binding, not by detection system or specimen [2] | Any staining indicates non-specific binding of secondary antibody or detection components |

| Isotype Control | Tissue incubated with non-immune antibody of the same isotype and concentration as primary antibody [2] [4] | Controls for non-specific interactions of the antibody with tissue components [2] | Background staining should be negligible and distinct from specific staining |

| Absorption Control | Tissue incubated with antibody pre-absorbed with excess immunogen [2] [3] | Demonstrates specificity of antibody binding to target antigen [2] | Little or no staining expected; more reliable with peptide immunogens [2] |

| Biological Negative Control | Tissue section known not to express the target protein [2] [3] | Checks for non-specific signal and false-positive results [2] | Any staining indicates non-specific binding or cross-reactivity |

A profoundly common error in IHC publications is the misuse of the "no primary antibody control" as evidence for the specificity of staining for the antigen targeted by the antibody [1]. This control only validates the specificity of the secondary antibody and detection system; it does not provide information about the primary antibody's specificity [1]. The proper negative control for primary antibody specificity is substitution with serum or isotype-specific immunoglobulins at the same protein concentration as the primary antibody [1].

Advanced Control Methodologies and Quantitative Applications

Innovative Control Technologies: Peptide-Based Standards

Emerging technologies have introduced peptide immunohistochemistry controls as a novel quality control format that offers advantages in high-throughput automated manufacture and standardization [5]. These controls consist of formalin-fixed peptide epitopes covalently attached to glass microscope slides, behaving immunochemically similarly to native protein in tissue sections [5].

In a national validation study involving 109 clinical laboratories, researchers demonstrated a strong correlation (r = 0.87) between a laboratory's ability to properly stain formalin-fixed peptide controls and their ability to properly stain a 3+ HER-2 formalin-fixed tissue section mounted on the same slide [5]. This technology enables quantitative quality assurance methods traditionally used in clinical chemistry laboratories, such as Levy-Jennings charting and Westgard rules, to be applied to IHC, facilitating improved assay precision and linearity [5].

Experimental Design and Validation Protocols

Proper validation of IHC assays requires systematic approaches and adherence to established guidelines. For laboratory-developed tests (LDTs) and modified FDA-cleared/approved tests, comprehensive validation is mandatory [6]. The College of American Pathologists (CAP) provides specific recommendations for validation cohorts:

- Predictive markers require a minimum of 20 positive and 20 negative cases [6]

- Non-predictive markers require a minimum of 10 positive and 10 negative cases [6]

- Overall concordance threshold of 90% is typically used, with any discordant results scrutinized to identify sensitivity or specificity issues [6]

The validation process involves multiple critical stages, including optimization to establish optimal staining conditions, validation/verification to confirm performance characteristics, clinical implementation, and ongoing assay maintenance through quality monitoring and proficiency testing [6].

Standardized Workflows and Visualization

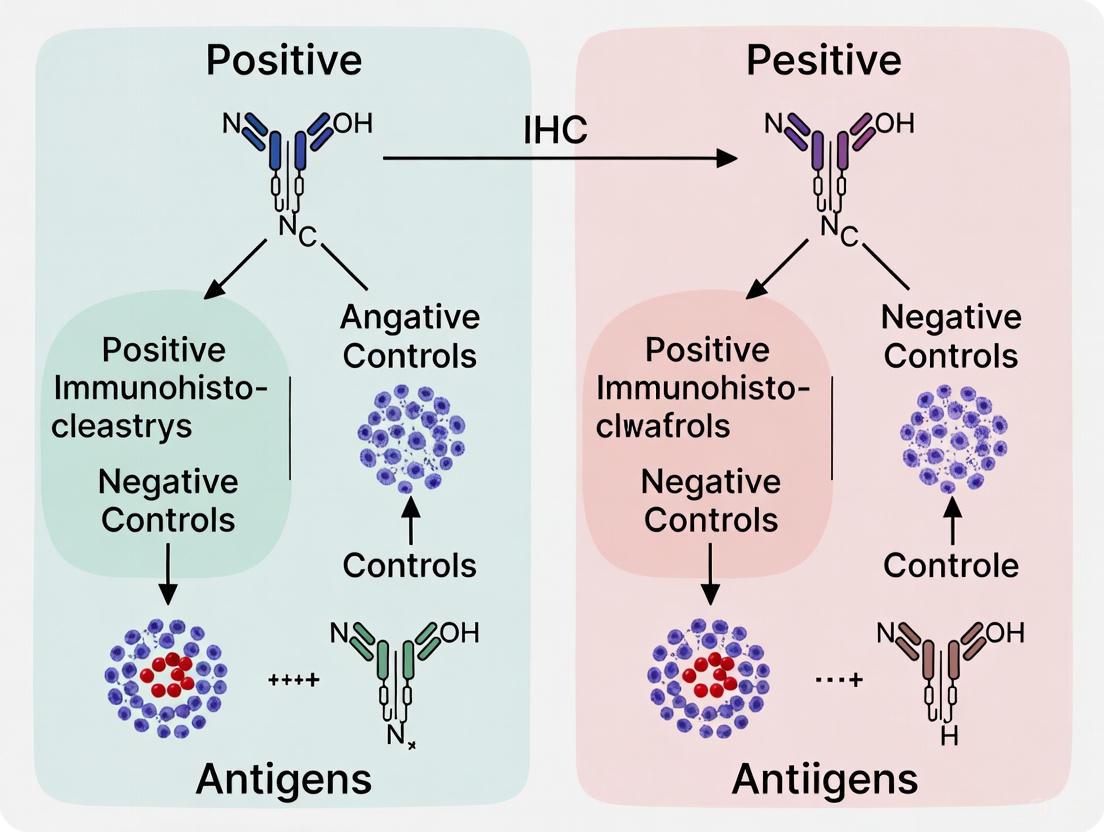

The complex workflow of IHC presents multiple variables that must be carefully controlled throughout the experimental process. The following diagram illustrates key decision points and control requirements in a standard IHC protocol:

IHC Experimental Workflow with Control Integration

Essential Reagents and Research Solutions

Successful IHC experimentation requires carefully selected reagents and materials, each serving specific functions in the staining workflow and validation process.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for IHC

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Antibodies | Monoclonal (clone-specific), Polyclonal | Recognize target epitopes; require validation for specific applications [7] [8] |

| Detection Systems | HRP-conjugated polymers, Avidin-biotin complexes | Amplify signal while minimizing background; critical for sensitivity [7] |

| Chromogens | DAB (brown), AP Red, AEC | Produce insoluble colored precipitate at antigen site [7] [9] |

| Antigen Retrieval Reagents | Citrate buffer (pH 6.0), EDTA (pH 8.0), Proteolytic enzymes | Reverse formaldehyde cross-linking to expose epitopes [9] [8] |

| Blocking Reagents | Normal serum, Casein, BSA | Reduce non-specific antibody binding and background staining [9] [4] |

| Control Materials | Known positive tissues, Isotype controls, Peptide arrays | Validate assay performance and antibody specificity [2] [5] |

| Fixation Media | Neutral buffered formalin, Paraformaldehyde | Preserve tissue architecture and antigenicity while preventing degradation [9] [10] |

Interpretation Framework and Troubleshooting

The following diagram provides a logical framework for interpreting control results and their implications for experimental validity:

Control Result Interpretation Decision Tree

Proper interpretation of IHC controls enables accurate troubleshooting of experimental issues:

- False-Positive Results: Occur when negative controls show staining, indicating non-specific binding of antibodies, inadequate blocking, or cross-reactivity [1] [3]

- False-Negative Results: Occur when positive controls fail to stain, indicating problems with antigen retrieval, antibody concentration, detection system sensitivity, or reagent degradation [1] [6]

- Inconsistent Staining: May result from variations in fixation, section thickness, or reagent application, highlighting the need for standardized protocols [7] [4]

Controls in immunohistochemistry are fundamentally non-negotiable components of experimental design, essential for producing valid, interpretable, and reproducible data. The integration of appropriate positive controls, multiple negative control modalities, and emerging technologies like peptide-based standards provides a robust framework for validating IHC assays. As the field moves toward increasingly quantitative applications, implementation of rigorous controls and standardized validation protocols becomes ever more critical. By adhering to these principles, researchers can ensure the reliability of their findings, contribute to reproducible science, and maintain confidence in the vital role of immunohistochemistry in both research and clinical diagnostics.

Defining Positive and Negative Tissue Controls

In immunohistochemistry (IHC), the validity of interpretations hinges entirely on the use of appropriate positive and negative controls [1]. These controls are not merely supplementary; they are fundamental components that help distinguish specific staining from artifacts, thereby ensuring the reliability and reproducibility of experimental results [11]. Without proper controls, investigators risk both false-positive and false-negative conclusions, which can lead to erroneous scientific conclusions and clinical misdiagnoses [1]. This guide objectively compares traditional tissue controls against innovative alternatives, providing researchers with a framework for implementing robust quality assurance in IHC workflows.

Core Principles of IHC Controls

Positive Tissue Controls

A positive tissue control is a specimen known to express the target antigen in a specific location (e.g., a particular cell type or intracellular compartment) [1]. Its purpose is to verify that the entire IHC protocol—from antigen retrieval to detection—is functioning correctly. A lack of staining in a positive control indicates a technical problem requiring protocol troubleshooting [11]. The most rigorous form is the positive anatomical control, which can be an internal site of known expression within the specimen itself or an external separate specimen known to contain the target [1].

Negative Tissue Controls

A negative tissue control is a specimen confirmed not to express the target protein [11]. Any observed staining in this control indicates non-specific binding or background interference, revealing potential false-positive results in test samples [11]. Knockdown (KD) and knockout (KO) tissues, where the expression of the target protein is significantly reduced or eliminated, are considered highly reliable negative controls [11].

Comparative Analysis of Control Methodologies

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of different control types used in IHC.

Table 1: Comparison of IHC Control Types and Their Applications

| Control Type | Definition & Purpose | Key Advantages | Inherent Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Patient Tissue Controls | Tissue sections from prior patient cases with known antigen expression status [12]. | Readily available in pathology departments; pathologists are familiar with interpretation. | Scarce for rare targets (e.g., ALK in lung cancer) [13] [14]; ethical issues around patient consent; heterogeneous expression [12]. |

| Genetically Modified Cell Lines (CLFs) | Cell suspensions from engineered cell lines that do or do not express the target antigen, applied in liquid form [13] [14]. | Consistent, renewable supply; defined expression levels; suitable for automated systems [13]. | May not fully recapitulate the complex tissue microenvironment of patient samples. |

| Isotype Controls | An antibody of the same class and host species as the primary antibody but with no target specificity [11]. | Controls for nonspecific binding mediated by the Fc region or other protein interactions [1]. | Does not validate the specificity of the primary antibody's paratope for its intended epitope. |

Performance Data: Traditional vs. Liquid Controls

A 2025 study on ALK testing in lung adenocarcinoma provides quantitative performance data for an automated system using Controls in Liquid Form (CLFs). The results demonstrate that the novel antibody and automated platform can achieve performance metrics on par with established clinical standards [13] [14].

Table 2: Performance Data of BP6165 Antibody with CLFs on LYNX480 PLUS Platform

| Performance Metric | Result | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 98.30% | Compared to FISH in 87 lung adenocarcinoma biopsy specimens [13] [14]. |

| Specificity | 100% | Compared to FISH in 87 lung adenocarcinoma biopsy specimens [13] [14]. |

| Control Application | More regular circular shape and better cell distribution vs. manual application. | Automated application of CLFs using the QC module of the LYNX480 PLUS system [13]. |

Experimental Protocols for Control Validation

Protocol: Establishing Controls in Liquid Form (CLFs)

The methodology below is adapted from a study validating ALK CLFs on an automated staining system [13] [14].

- Materials: Genetically modified cell lines (e.g., ALK positive CLF Catalog No.: BX30026P and ALK negative CLF Catalog No.: BX30026N), automated IHC staining system with QC module (e.g., LYNX480 PLUS), slides, and optimized IHC reagents.

- CLF Application: Use the system's QC module to automatically pipette CLFs onto target slides by scanning the quick response (QR) code on the CLF vial. The droplet is then dried and fixed in minutes using a built-in heater.

- Staining Protocol: Perform IHC using the optimized protocol. For the cited study, this included antigen retrieval with EDTA (pH 9.0) at 100°C for 60 min, peroxidase block for 5 min, incubation with primary antibody (e.g., BP6165 at 1:200 dilution) for 30 min at room temperature, and detection with a conventional DAB system [13].

- Validation: Compare the staining pattern, droplet shape, and cell distribution of automatically applied CLFs against manually applied ones. The method yielding superior consistency and a more regular circular shape should be selected for clinical use [13].

Protocol: Traditional Control Validation as per CAP Guidelines

The College of American Pathologists (CAP) updated its guidelines in 2024, providing a standardized framework for IHC assay validation [15] [16].

- Validation Scope: All laboratory-developed IHC assays must be analytically validated, and all FDA-cleared/approved assays must be verified before reporting patient results [16].

- Sample Size: For initial analytic validation of laboratory-developed assays, a minimum of 10 positive and 10 negative tissues is required. For predictive marker assays (e.g., HER2, ALK, PD-L1), a minimum of 20 positive and 20 negative tissues is required [15] [16].

- Concordance Requirement: Laboratories must achieve at least 90% overall concordance between the new assay and the comparator method or expected results [15] [16].

- Comparator Methods: Validation can use several comparators, ordered here from most to least stringent:

- Comparison to IHC results from protein-calibrated cell lines.

- Comparison with a non-IHC method (e.g., FISH, flow cytometry).

- Comparison with results from another laboratory using a validated assay.

- Comparison with prior testing of the same tissues in the same lab.

- Comparison against expected architectural and subcellular localization [15].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Consistent IHC Results

| Reagent / Material | Function | Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|

| Antigen Retrieval Solutions | Reverses formaldehyde-induced crosslinks to unmask epitopes (e.g., Citrate or EDTA buffer) [17]. | The optimal solution (HIER vs. enzymatic) and pH are antibody-dependent and must be determined during validation [17]. |

| Antibody Diluent | Dilutes the primary antibody to the working concentration. | The choice of diluent can dramatically affect signal strength and must be optimized for each antibody [17]. |

| Blocking Buffers | Reduces nonspecific binding of antibodies to tissue components (e.g., normal serum, animal-free blockers) [17]. | Helps minimize background staining. |

| Detection System | A polymer-based reagent that binds the primary antibody and generates a visible signal (chromogenic or fluorescent) [17]. | Biotin-free, polymer-based systems avoid background from endogenous biotin and offer enhanced sensitivity [17]. |

| Chromogen (e.g., DAB) | Forms an insoluble, colored precipitate at the site of antibody binding [13] [17]. | Different DAB substrate kits vary in sensitivity; the substrate should be qualified with the detection system [17]. |

| 2-(Decan-2-YL)thiophene | 2-(Decan-2-yl)thiophene|High-Purity Reference Standard | 2-(Decan-2-yl)thiophene is a high-purity thiophene derivative for research applications in medicinal chemistry and material science. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 3-Chlorooctane-1-thiol | 3-Chlorooctane-1-thiol, CAS:61661-23-2, MF:C8H17ClS, MW:180.74 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Technological Innovations and Workflow Integration

The IHC control workflow is evolving with new technologies that complement traditional methods. Automated staining systems with integrated quality control modules, such as the LYNX480 PLUS, can standardize the application of liquid controls [13] [14]. Furthermore, artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms are now being used to quantitatively monitor staining quality and trace variations in control cell lines over time, offering an objective alternative to visual assessment [12]. In the research domain, deep generative models are being explored for "virtual staining," which aims to predict IHC staining patterns from H&E-stained images, though this remains an emerging technology [18].

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for IHC quality control, combining traditional and novel approaches.

The definitive establishment of positive and negative controls remains a non-negotiable standard in IHC for both research and clinical diagnostics. While traditional patient tissue controls are a familiar benchmark, their limitations—scarcity, heterogeneity, and ethical concerns—are driving the adoption of innovative alternatives [13] [14] [12]. Genetically defined controls in liquid form (CLFs) offer a standardized, renewable resource that is particularly well-suited for automated platforms and demonstrates excellent performance in analytical validation [13] [14]. Adherence to updated evidence-based guidelines, such as those from CAP, and the strategic integration of new technologies like AI-powered quality monitoring, provides a robust pathway for laboratories to ensure the accuracy, reliability, and reproducibility of their IHC assays, which is fundamental for both scientific discovery and patient care [15] [12] [16].

In immunohistochemistry (IHC), the validity of experimental results hinges on the proper use of controls that distinguish specific staining from background artifacts. Negative reagent controls are essential for demonstrating that observed staining results from specific antibody-antigen interactions rather than non-specific binding. Among these, the no primary antibody control and isotype control serve distinct but complementary roles in validating IHC specificity. These controls are particularly crucial in diagnostic IHC and research applications where false-positive results could lead to incorrect scientific conclusions or clinical misdiagnoses [1] [19]. This guide examines the principles, applications, and experimental implementation of these two fundamental negative controls within the broader context of IHC quality assurance.

Theoretical Foundations: How Negative Reagent Controls Work

The Problem of Background Staining

Background staining in IHC can arise from multiple sources. Fc receptors present on various cell types (including B cells, macrophages, monocytes, and dendritic cells) can bind the constant (Fc) region of antibodies independently of their antigen specificity. Additional sources include cellular autofluorescence, non-specific antibody interactions with lipids, carbohydrates, or other cellular molecules, and endogenous enzymes that interact with detection systems [20] [21]. Without appropriate controls, this background staining can be misinterpreted as specific signal, compromising experimental validity.

The Role of Negative Reagent Controls

Negative reagent controls are designed to identify the source and extent of non-specific background staining. They help researchers distinguish true positive signals from artifacts caused by non-specific binding, autofluorescence, or protocol errors [22]. According to expert guidelines, the proper use of negative controls is essential for building a convincing case for the presence or absence of a probed molecule in tissue samples [1].

Direct Comparison: No Primary Antibody vs. Isotype Controls

Table 1: Characteristics of Negative Reagent Controls in IHC

| Parameter | No Primary Antibody Control | Isotype Control |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Detects non-specific binding of secondary antibody and detection system [1] [22] | Evaluates non-specific binding caused by the constant (Fc) region of the primary antibody [20] [21] |

| Preparation | Primary antibody omitted and replaced with antibody diluent; all other steps unchanged [22] | Primary antibody replaced with matched isotype antibody at same concentration [20] [21] |

| What It Identifies | Secondary antibody non-specificity, endogenous enzyme activity, inadequate blocking [1] | Fc receptor binding, non-specific interactions via Fc region [20] [21] |

| Limitations | Does not control for primary antibody non-specificity [1] | Does not detect Fab-mediated non-specific binding [21] |

| Optimal Result | No staining observed [22] | Minimal to no staining observed [20] |

| Required Matching Parameters | None for primary antibody | Host species, isotype, subclass, conjugation, concentration [20] [21] |

Table 2: Application Scenarios for Negative Controls

| Experimental Scenario | Recommended Control | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Initial assay validation | Both controls | Comprehensive assessment of both secondary and primary antibody issues [19] |

| Routine IHC staining | No primary antibody control (if using polymer-based detection systems) | CAP guidelines indicate this may be sufficient for polymer-based systems [19] |

| Working with Fc receptor-rich tissues (spleen, lymph nodes) | Isotype control essential | High likelihood of Fc-mediated binding [20] [21] |

| Using new primary antibody | Both controls | Complete characterization of antibody performance [20] |

| Troubleshooting high background | Sequential application | Identify specific source of background staining [22] |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Protocol for No Primary Antibody Control

- Sample Preparation: Use serial sections from the same tissue block as test samples [19]

- Fixation and Processing: Identical to test sections

- Primary Antibody Step: Omit primary antibody and incubate with antibody diluent only [22]

- Detection System: Apply the same secondary antibody and detection reagents as test sections

- Visualization: Use identical chromogenic or fluorescent development conditions

- Interpretation: Any staining observed indicates non-specific binding of the secondary antibody or detection system components [1]

Protocol for Isotype Control

- Control Selection: Choose an isotype control antibody that matches:

- Concentration Matching: Use the same concentration (μg/mL) as the primary antibody [21]

- Incubation Conditions: Identical temperature, duration, and buffer conditions

- Detection: Use the same detection system and development conditions

- Interpretation: Staining indicates non-specific binding via the Fc region; true specific staining should significantly exceed isotype control staining [20]

Advanced Applications in Precision Oncology and Drug Development

The proper implementation of negative controls has become increasingly important in translational research and precision medicine. With the expansion of companion diagnostics and targeted therapies, IHC assays for biomarkers such as ALK, PD-L1, HER2, and TROP2 require exceptional specificity [23] [14]. For example, in ALK IHC testing for lung adenocarcinoma, appropriate controls are essential for determining patient eligibility for ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitors [14].

Recent advancements include the development of automated quality control systems that incorporate standardized controls in liquid form (CLFs) prepared from genetically modified cell lines. These systems provide consistent application of controls and reduce the consumption of scarce patient tissue resources [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Implementing Negative Controls

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function in Negative Controls |

|---|---|---|

| Isotype Controls | Mouse IgG1 [MOPC-21], Mouse IgG2b [MPC-11], Chicken IgY | Matched non-specific antibodies for detecting Fc-mediated binding [21] |

| Antibody Diluents | Protein-stabilized buffers with carrier proteins | Maintain consistent protein concentration when omitting primary antibody [22] |

| Polymer-Based Detection Systems | HRP-polymer conjugates, AP-polymer conjugates | Reduce endogenous biotin interference; decrease need for negative reagent controls [19] |

| Blocking Reagents | Normal serum, BSA, non-fat dry milk | Reduce non-specific binding; critical for both controls [24] |

| Automated Staining Systems | VENTANA BenchMark, LYNX480 PLUS | Standardize application of controls and test antibodies [14] |

| 2-Undecene, 5-methyl- | 2-Undecene, 5-methyl-, CAS:56851-34-4, MF:C12H24, MW:168.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3-Chloro-1-methoxyheptane | 3-Chloro-1-methoxyheptane, CAS:53970-69-7, MF:C8H17ClO, MW:164.67 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Both no primary antibody controls and isotype controls are essential components of a rigorous IHC quality control program. While the no primary antibody control specifically addresses non-specific binding of the detection system, the isotype control evaluates Fc-mediated non-specific binding of the primary antibody itself. The optimal use of these controls depends on the experimental context, with comprehensive validation requiring both controls during initial assay development. As IHC continues to evolve with multiplexed staining, digital pathology, and AI-assisted analysis, proper implementation of these fundamental controls remains essential for generating reliable, reproducible data in both research and diagnostic applications.

The Principle of the Blocking Peptide (Pre-absorption) Control

The blocking peptide control, also known as the pre-absorption control, serves as a critical experimental tool for validating antibody specificity in immunohistochemistry (IHC) and other immunoassays. This control operates on the principle of competitive binding, where the antibody is pre-incubated with an excess of the immunizing peptide before application to the tissue sample. When properly executed, this process should abolish specific staining, confirming that the antibody binding is target-specific. This guide examines the technical performance, experimental protocols, and limitations of the blocking peptide control within the broader context of IHC positive and negative controls, providing researchers with objective data for informed experimental design.

Immunohistochemistry relies on the specific recognition of an epitope by an antibody to visualize protein expression within the context of preserved tissue structure [25]. However, antibody binding is susceptible to non-specific interactions that can generate false positive results, compromising data interpretation. The blocking peptide control addresses this vulnerability by providing a mechanism to distinguish specific from non-specific binding [26]. Within the hierarchy of IHC controls, which includes no-primary controls, isotype controls, and tissue controls, the pre-absorption control serves as a unique negative control that directly probes antibody-epitope interaction specificity [27] [28]. Unlike tissue controls that validate overall assay performance, the blocking peptide control specifically validates the antibody reagent itself, making it an indispensable tool for rigorous antibody validation, particularly for polyclonal antibodies which recognize multiple epitopes and are more prone to non-specific binding [29].

Fundamental Principle and Mechanism

The core principle of the blocking peptide control revolves around competitive binding. Blocking peptides are short amino acid sequences corresponding to the specific epitope recognized by the primary antibody [26]. These peptides are identical to the antigenic sequence used during antibody generation, allowing them to bind with high affinity to the antibody's paratope [30].

The mechanism follows these essential steps:

- Pre-incubation: The primary antibody is incubated with an excess of blocking peptide before application to the tissue section [29] [30].

- Binding Site Occupation: The blocking peptide binds specifically to the antibody's antigen-binding sites, occupying all available paratopes [26].

- Neutralization: The antibody, now complexed with peptide, is functionally "neutralized" and unable to bind to the target epitope present in the tissue sample [29].

- Specific Signal Abolition: When this blocked antibody solution is applied to the tissue, any staining that disappears compared to the control (antibody alone) is confirmed as specific binding [29] [30].

The critical interpretation is straightforward: complete or substantial loss of signal in the blocked sample confirms the antibody's specificity for the target epitope, while persistent staining indicates non-specific binding to off-target epitopes [27] [30].

Figure 1 | Competitive Binding Mechanism of Blocking Peptide Control. The primary antibody is pre-incubated with the blocking peptide, forming a complex that cannot bind the target epitope in the tissue, resulting in no signal. In standard IHC, the unblocked antibody binds the epitope, producing a detectable signal.

Comparative Performance of IHC Controls

A comprehensive IHC validation strategy employs multiple control types, each with distinct functions and limitations. The blocking peptide control occupies a specific niche, primarily addressing antibody specificity rather than overall assay conditions.

Table 1: Comparison of Key IHC Negative Controls

| Control Type | Primary Function | Key Interpretation | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blocking Peptide [27] [29] [26] | Validate antibody specificity for the target epitope. | Loss of signal confirms specific binding. | - May block specific and cross-reactive binding equally [31].- Peptide may itself bind tissue non-specifically [28]. |

| No Primary Antibody [27] [28] | Detect non-specific binding of secondary antibody and detection reagents. | No staining should be observed. | Does not validate primary antibody specificity. |

| Isotype Control [28] | Assess non-specific binding caused by the immunoglobulin framework. | Staining should not resemble specific pattern. | Does not confirm that the primary antibody's paratope binds the correct target. |

| Negative Tissue Control [27] | Identify non-specific antibody binding in a biological context. | No staining in known negative tissue. | Genetically modified tissues (KO/KD) can be difficult to obtain [27]. |

The blocking peptide control is particularly powerful because it directly probes the antibody-antigen interaction. However, a significant limitation noted in peer-reviewed literature is that pre-absorption can block all antibody binding—both to the intended target and to cross-reactive epitopes. This can create an illusion of specificity if the antibody cross-reacts with non-target proteins, as the blocking peptide will abolish all staining, misleading the researcher into believing the antibody is specific [31]. Therefore, this control should be used in conjunction with other validation methods, such as tissue controls from knockout animals, for conclusive specificity determination [31].

Detailed Experimental Protocol and Reagents

Implementing a robust blocking peptide control requires careful attention to reagent preparation and incubation conditions. The following protocol is adapted from established methodologies [29] [30].

Reagent Preparation

- Blocking Buffer: Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 1% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) is commonly used for IHC [29].

- Antibody Solution: Prepare the primary antibody at its predetermined optimal working dilution in blocking buffer. A typical solution may contain 97.65% PBS, 0.3% Triton X-100 (0.05% for extracellular targets), 0.05% Tween-20, and 2% normal serum from the species in which the secondary antibody was raised [30].

- Blocking Peptide Solution: Reconstitute lyophilized peptide according to the manufacturer's datasheet, typically in sterile PBS [30].

Step-by-Step Protocol

- Preparation: Prepare identical tissue sections on slides, following standard fixation, permeabilization, and (if required) antigen retrieval protocols [30] [25].

- Antibody Division: Dilute the primary antibody to its optimal concentration and divide the solution equally into two tubes labeled "Antibody Alone" and "Antibody + Peptide" [29] [30].

- Peptide Incubation: To the "Antibody + Peptide" tube, add the blocking peptide. A 10-fold weight excess of peptide relative to the antibody is widely recommended to ensure complete saturation of binding sites [30] [28]. For example, if using 1 µg of antibody in 2 mL of buffer, add at least 10 µg of total peptide [29].

- Incubation: Incubate the "Antibody + Peptide" mixture with agitation for 1 hour at room temperature or overnight at 4°C [29] [30].

- Staining: Apply the "Antibody Alone" solution to one tissue section and the "Antibody + Peptide" solution to the duplicate section. Process both slides simultaneously through the remaining IHC steps (secondary antibody incubation, detection, counterstaining, mounting) under identical conditions [29].

- Imaging and Analysis: Image both slides using the same microscope and settings. Compare the staining patterns. The specific signal will be absent or drastically reduced in the peptide-blocked sample [29] [30].

Figure 2 | Blocking Peptide Control Workflow. The primary antibody solution is divided, and one portion is pre-incubated with a excess of blocking peptide. Both solutions are applied to duplicate tissue sections and processed identically. Loss of signal in the peptide-blocked sample confirms specific antibody binding.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Blocking Peptide Experiments

| Reagent | Function | Critical Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Antibody | Binds specifically to the target protein of interest in the tissue. | Host species, clonality (monoclonal/polyclonal), and optimal working dilution must be predetermined. |

| Blocking Peptide [29] [26] [30] | Competes with the tissue antigen for binding to the primary antibody's paratope. | Must correspond exactly to the immunogen sequence used to generate the antibody. |

| Normal Serum [30] | Blocks non-specific binding sites in the tissue to reduce background noise. | Should be from the same species as the host of the secondary antibody. |

| Secondary Antibody | Conjugated to a fluorophore or enzyme, it binds the primary antibody for detection. | Must be highly cross-adsorbed against immunoglobulins from other species to minimize cross-reactivity. |

| lithium;prop-1-enylbenzene | Lithium;prop-1-enylbenzene|C9H9Li | Lithium;prop-1-enylbenzene (C9H9Li) is an organolithium compound for research, notably in polymer synthesis. This product is For Research Use Only. |

| Peroxide, nitro 1-oxohexyl | Peroxide, nitro 1-oxohexyl|C6H11NO5|[Your Company] | Peroxide, nitro 1-oxohexyl (C6H11NO5) is For Research Use Only. It is a high-purity reagent for specialized chemical research. Not for human or veterinary use. |

The blocking peptide control remains a fundamental tool for demonstrating antibody specificity in IHC workflows. Its direct mechanism of action, which competitively inhibits antibody binding, provides compelling evidence that an observed staining pattern is specific. However, researchers must be aware of its principal limitation: a positive result (loss of signal) confirms the antibody is binding to the peptide's sequence, but does not definitively rule out cross-reactivity with other proteins containing similar epitopes [31].

Therefore, within a robust IHC validation framework, the blocking peptide control should be considered a necessary but not sufficient test for antibody specificity. It functions most effectively when integrated with a panel of other controls, including no-primary controls, isotype controls, and—most definitively—genetically validated negative tissue controls (e.g., knockout tissues) [27] [31]. For researchers and drug development professionals, this multi-pronged approach to antibody validation, incorporating the blocking peptide control as a key element, is essential for generating reliable, interpretable, and reproducible data that can confidently support scientific conclusions and therapeutic development.

Assessing Endogenous Background and Autofluorescence

In immunohistochemistry (IHC) and immunofluorescence (IF), the accurate detection of specific antibody-antigen interactions is paramount. However, non-specific signals from endogenous background and autofluorescence can profoundly compromise data integrity, potentially leading to false positives and erroneous biological interpretations [32] [33]. These phenomena represent a significant challenge in both research and clinical diagnostics, as they can obscure specific signals, reduce assay sensitivity, and increase background noise [32] [34].

Within the critical framework of positive and negative controls for IHC experiments, understanding and managing autofluorescence is a cornerstone of robust assay validation [35]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the primary sources of these non-specific signals and the methods available to assess and mitigate them, providing researchers with the experimental data and protocols necessary to enhance the reliability of their imaging data.

Endogenous background and autofluorescence arise from different mechanisms. Endogenous background typically refers to non-antibody-mediated signals, such as enzymatic activity or endogenous biotin [33]. In contrast, autofluorescence is the inherent fluorescence emitted by certain molecules when excited by light, which is prominent in the green channel and can interfere with common fluorophores like Alexa Fluor 488 and FITC [32].

The table below catalogs the common sources of these non-specific signals and their origins.

Table 1: Common Sources of Non-Specific Signal in Biological Samples

| Source Type | Specific Source | Description / Cause of Interference |

|---|---|---|

| Endogenous Molecules | Collagen & Elastin | Components of the extracellular matrix that autofluoresce [32] [33]. |

| Lipofuscin | A pigmented byproduct of intracellular catabolism that accumulates in post-mitotic cells like neurons and myocytes [32]. | |

| Riboflavin (B2), NADH | Metabolic coenzymes with inherent fluorescence [32] [33]. | |

| Heme Groups | Found in red blood cells and hemoproteins like hemoglobin; a common cause of background [32] [33]. | |

| Aromatic Amino Acids | Phenylalanine, tryptophan, and tyrosine [32]. | |

| Fixation-Induced | Aldehyde Fixatives | Formaldehyde and glutaraldehyde can react with amine groups to form fluorescent Schiff's bases [32] [33]. |

| Laboratory Reagents | Phenol Red | A media supplement that should be avoided for live-cell imaging [32]. |

| Plastic Ware | Plastic microplates and cell culture flasks can autofluoresce [32]. |

Assessment and Comparison of Mitigation Strategies

Various strategies have been developed to manage autofluorescence, each with distinct principles, advantages, and limitations. The choice of method depends on factors such as sample type, fixation method, and the application being performed [32].

Fluorophore Selection and Spectral Resolution

Choosing fluorophores that emit in spectral regions with low sample autofluorescence is a straightforward and effective first step. Near-infrared (NIR) fluorophores are particularly valuable as autofluorescence is often most prominent in the green spectrum [32]. For researchers using GFP tags, which are susceptible to interference, switching to an anti-GFP antibody conjugated to a fluorophore in a different channel (e.g., red) can move the signal away from the green autofluorescence [32].

Advanced instrumentation like spectral flow cytometry and fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) offer powerful solutions by separating the specific immunofluorescence signal from the autofluorescence based on their full spectral signatures or fluorescence decay rates, respectively [32].

Chemical and Photobleaching Treatments

Several chemical treatments can effectively reduce autofluorescence. Sudan black B has been successfully used to quench autofluorescence in various tissues, including murine renal tissue [32]. Similarly, incubation in a solution of 5% Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ can help reduce background [32]. For aldehyde-induced fluorescence, treatment with sodium borohydride (e.g., 1 mg/mL for 30-40 minutes) neutralizes Schiff's bases by reducing them into non-fluorescent salts [32].

Photobleaching, which involves exposing the sample to strong light prior to antibody incubation, can also diminish autofluorescence by bleaching the fluorescent molecules present in the sample before the experimental staining [32].

Comparative Analysis of Mitigation Techniques

The following table provides a structured comparison of the primary methods for managing autofluorescence, summarizing key experimental data and considerations.

Table 2: Comparison of Autofluorescence Mitigation Strategies

| Method | Principle | Key Experimental Protocol / Data | Advantages | Limitations / Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spectral Imaging | Separates signals based on full spectral signature [32]. | Used in spectral flow cytometry and fluorescence lifetime imaging (FLIM) [32]. | High-information content; can resolve multiple targets. | Requires specialized, often expensive, instrumentation. |

| Chemical Quenching (Sudan Black B) | Binds to and quenches autofluorescent compounds [32]. | Incubate tissue sections with 0.1-0.3% Sudan Black B for 20-30 minutes followed by washing [32]. | Effective against broad-spectrum autofluorescence (e.g., from lipofuscin). | Can negatively affect specific signal if not optimized [35]. |

| Chemical Quenching (Sodium Borohydride) | Reduces fluorescent Schiff's bases formed by aldehyde fixatives [32]. | Treat aldehyde-fixed samples with 1 mg/mL sodium borohydride for 30-40 minutes [32]. | Highly specific for fixation-induced fluorescence. | Can be harsh on some tissue antigens. |

| Photobleaching | Uses high-intensity light to bleach endogenous fluorophores prior to staining [32]. | Expose unstained sample to intense light at relevant wavelengths for a defined period. | Simple; no chemicals added to the sample. | Can also bleach the specific fluorophore if not carefully controlled. |

| Alternative Fixation | Uses non-aldehyde fixatives to prevent Schiff's base formation [32] [10]. | Fix samples with ice-cold methanol or acetone for 5-15 minutes [32]. | Avoids the root cause of aldehyde autofluorescence. | May not preserve morphology or antigenicity as well as aldehydes for some targets [10]. |

The workflow for selecting and applying these strategies can be visualized as follows:

Essential Protocols for Assessment and Control

Protocol: Evaluating Sample Autofluorescence

The first step in addressing autofluorescence is to quantify its level and spectral characteristics in your specific sample [32].

- Prepare an Unstained Control: Process your tissue sample or cells identically to your standard IHC/IF protocol, including fixation, permeabilization, and mounting, but omit all fluorescently-labeled reagents (primary and secondary antibodies) [32].

- Image the Control: Observe the unstained control using all the microscope filter sets or laser lines you plan to use in your experiment.

- Analyze the Signal: The fluorescence signal detected in this unstained control represents the level and distribution of autofluorescence for your sample under those imaging conditions. This provides a critical baseline for subsequent optimization.

Protocol: Sodium Borohydride Treatment for Aldehyde-Induced Fluorescence

This protocol is specifically for reducing autofluorescence caused by aldehyde fixatives like formaldehyde and glutaraldehyde [32].

- Prepare Solution: Freshly prepare a 1 mg/mL solution of sodium borohydride in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Note: The solution will bubble as the borohydride reacts with water.

- Treat Sample: Incubate the aldehyde-fixed sample (tissue section or cells) in this solution for 30 to 40 minutes at room temperature.

- Wash: Rinse the sample thoroughly with PBS, 3 times for 5 minutes each, to remove any residual reagent.

- Proceed with Staining: Continue with your standard immunostaining protocol.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Successfully managing autofluorescence requires a combination of specific reagents and analytical tools. The following table details essential items for this process.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Autofluorescence Management

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Sudan Black B | A chemical quencher used to reduce broad-spectrum autofluorescence from sources like lipofuscin [32] [35]. |

| Sodium Borohydride | A reducing agent that neutralizes fluorescent Schiff's bases formed by aldehyde fixatives [32]. |

| Near-Infrared (NIR) Fluorophores | Fluorophores emitting in the near-infrared range, spectrally distant from common green-channel autofluorescence [32]. |

| Anti-GFP Antibody Conjugates | Antibodies against GFP, conjugated to fluorophores in red or other channels, allowing detection of GFP-tagged proteins away from the congested green spectrum [32]. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) | Used in treatments (e.g., overnight incubation in 5% Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) to reduce autofluorescence in certain tissues [32]. |

| Methanol/Acetone | Non-aldehyde, precipitative fixatives used as an alternative to formaldehyde to prevent the formation of fluorescent Schiff's bases [32] [10]. |

| Spectral Flow Cytometer or FLIM Microscope | Advanced instrumentation that separates specific signal from autofluorescence based on full spectral signatures or fluorescence decay kinetics [32]. |

| Viability Dye | In flow cytometry, used to gate out dead cells and debris, which often exhibit high levels of autofluorescence [32]. |

| 1H-Pyrrole, dimethyl- | 1H-Pyrrole, dimethyl-, CAS:49813-61-8, MF:C12H18N2, MW:190.28 g/mol |

| N-trimethylsilylazetidine | N-Trimethylsilylazetidine|CAS 41268-75-1 |

A Step-by-Step Protocol for Implementing Essential IHC Controls

Sourcing and Selecting Appropriate Positive and Negative Control Tissues

In immunohistochemistry (IHC), the validity of interpretations hinges entirely on the use of appropriate positive and negative controls. These controls serve as internal checks that differentiate true positive signals from artefacts caused by nonspecific binding, endogenous activity, or protocol errors [36] [37]. Without proper controls, investigators risk publishing unverified and irreproducible findings, which wastes time, resources, and erodes scientific credibility [1]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of control tissue sourcing strategies and selection methodologies to ensure reliable, interpretable IHC results for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Understanding Control Types and Their Functions

Positive Control Tissues

Positive tissue controls are specimens known to express the target protein in a specific location (specific cell type or intracellular compartment) [1]. A positive control demonstrates that the entire IHC assay is functioning correctly—from antigen retrieval to detection. If staining is observed in the positive control, the protocol is working; lack of staining indicates a technical issue requiring troubleshooting [37].

The most rigorous positive control is the positive anatomical control, which can be either:

- Internal positive control: A known site of target expression within the test specimen itself [1]

- External positive control: A separate specimen/slide known to contain the molecule targeted by the antibody [1]

Negative Control Tissues

Negative tissue controls reveal non-specific binding and false positive results [37]. These controls should come from tissues that do not express the target protein [37]. Any observed staining suggests non-specific binding, indicating potential issues with antibody specificity or protocol conditions.

Specialized Control Types

Beyond basic positive and negative controls, several specialized controls address specific experimental challenges:

- No Primary Controls (Secondary Antibody Only Control): Assesses nonspecific binding by the secondary antibody by omitting the primary antibody [37]

- Isotype Controls: Uses an antibody of the same class, clonality, and host species as the primary antibody but with no specificity to the target antigen [37]

- Absorption Controls: Tests if the primary antibody binds specifically by pre-incubating it with the immunogen before application [37]

- Endogenous Tissue Background Controls: Identifies inherent biological properties that emit natural fluorescence or produce color [37]

Sourcing Strategies for Control Tissues

Sourcing appropriate control tissues presents significant challenges, particularly for rare antigens or low-incidence biomarkers. The table below compares various sourcing strategies with their advantages and limitations:

Table 1: Comparison of Control Tissue Sourcing Strategies

| Sourcing Method | Best For | Sample Requirements | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Laboratory Archives [38] | Common antigens, retrospective studies | Variable, depends on archive size | Readily accessible, known processing history | Limited availability for rare antigens |

| Tissue Microarray (TMA) Blocks [38] | High-throughput validation | 10-20 positive/negative cases [38] | Space-efficient, multiple tissues on one slide | May not contain rare antigens needed |

| Commercial Cell Lines [12] [39] | Protein quantification, standardized controls | Cell pellets with known expression levels [39] | Highly standardized, unlimited supply | May lack tissue context, dynamic range issues [1] |

| Xenograft Models [39] | Cancer research, phospho-specific targets | Cell lines with known expression [39] | Controlled expression levels, human targets in mouse context | Complex preparation, not for all targets |

| Multi-institutional Collaborations [38] | Rare diseases, low-incidence antigens | Varies by rarity | Access to otherwise unavailable specimens | Complex logistics, IRB approvals |

| Homemade Multitissue Blocks [38] | Maximizing resource utilization | Small fragments from multiple sources | Cost-effective, customizable | Requires expertise to create |

Addressing the Rare Antigen Challenge

For antigens with low population frequency (e.g., ALK+ lymphoma comprising only 2-3% of all lymphomas), finding sufficient positive cases presents unique challenges [38]. Practical solutions include:

- Laboratory Information System Mining: Prospective and retrospective searches of archival material [38]

- External Quality Assessment Programs: Supplementation with in-house tissues to reach optimal case numbers [38]

- Literature Correlation: Correlating staining patterns with expected results when tissues are unavailable [38]

- Tissue Multiplexing: Combining multiple tissue types in single blocks to maximize resource utilization [38]

According to College of American Pathologists (CAP) guidelines, laboratories should aim for:

- Nonpredictive assays: Minimum of 10 positive and 10 negative cases [38]

- FDA-approved predictive assays: Minimum of 20 positive and 20 negative/low-expressor cases [38]

- Laboratory Developed Tests (LDTs): Minimum of 40 positive and 40 low-expressor/negative cases [38]

Selection Criteria for Appropriate Control Tissues

Factors in Tissue Selection

Selecting appropriate control tissues requires consideration of multiple factors:

- Antigen Expression Level: Tissues should demonstrate expected expression patterns based on literature or previous studies [1]

- Tissue Morphology Preservation: Proper fixation and processing are essential—over-fixed tissues may mask antigens, while under-fixed tissues may exhibit excessive background [36]

- Species Compatibility: Consider species-specific reactions, particularly for mouse-on-mouse applications [40] [41]

- Fixation Method Consistency: Control and test tissues should undergo identical fixation protocols [15]

Validation of Specificity

Essential to valid interpretation of IHC staining is selecting antibodies validated to detect specific epitopes [1]. Validation approaches include:

- Western Blot Analysis: Demonstrates specific bands of appropriate molecular weight [39]

- Cell Line Transfection: Paraffin-embedded cell pellets with known target expression levels verify specificity [39]

- Blocking Peptides: Verify specificity and rule out Fc-mediated binding and non-specific staining [39]

- Genetic Validation: Antibodies should not produce staining in genetically engineered knockout models [1]

Figure 1: Control Tissue Selection and Validation Workflow

Special Considerations for Complex Scenarios

Mouse-on-Mouse Staining

Using mouse primary antibodies on mouse tissues presents unique challenges due to endogenous IgGs that secondary antibodies can recognize, causing high background [40] [41]. Mitigation strategies include:

- Direct Immunohistochemistry: Using directly conjugated primary antibodies eliminates secondary antibody issues [40] [41]

- Pre-blocking with Fab Fragments: Blocking endogenous IgGs by pre-treating tissue with unconjugated Fab fragments [41]

- Pre-formed Antibody Complexes: Mixing primary and secondary antibodies before application reduces free secondary antibodies [40]

Table 2: Mouse-on-Mouse Background Reduction Techniques

| Technique | Mechanism | Best For | Protocol Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Conjugation [40] | Eliminates secondary antibody | Any application, especially multiplexing | Low (commercial) to High (in-house) |

| Fab Fragment Blocking [41] | Blocks endogenous IgG epitopes | Tissues with high blood content | Medium |

| Pre-formed Complexes [40] | Binds secondary before application | Low abundance targets | High |

| Animal Perfusion [40] | Reduces blood-derived IgG | Pre-clinical models | Highest |

Endogenous Activity Interference

Certain tissues possess inherent properties that complicate IHC interpretation:

- Endogenous Enzyme Activity: Tissues rich in peroxidases (spleen, kidney) or phosphatases (kidney, intestine, liver) can react with chromogenic substrates, creating high background in IHC [36]

- Endogenous Biotin: Tissues with high mitochondrial activity (kidney, liver, spleen, tumors) contain high biotin levels, interfering with avidin-biotin detection systems [36]

- Autofluorescence: Molecules including heme groups, collagen, elastin, NADH, and lipofuscin emit natural fluorescence, particularly problematic in green and red channels [36]

Quality Assurance and Emerging Technologies

Monitoring Staining Variations

Quality control of IHC slides is crucial for accurate interpretation. Traditional methods use visual assessment, but emerging technologies offer improved standardization:

- Image Analysis Algorithms: AI-based tools like Qualitopix can quantify expression levels and detect variations not apparent visually [12]

- Standardized Cell Lines: Provide consistent control material across multiple experiments and sites [12]

- Inter-stainer Monitoring: AI algorithms can detect variations between different staining instruments and even individual slide slots [12]

Regulatory and Accreditation Standards

Adherence to established guidelines ensures testing standardization:

- CAP Guidelines: Require separate validation for each assay-scoring system combination and different fixation methods [15]

- Concordance Requirements: CAP updated guidelines set uniform 90% concordance requirements for all IHC assays [15]

- Documentation: Even for established assays, lack of validation documentation may result in accreditation citations [15]

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Control Tissue Experiments

| Reagent/Category | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Primary Antibodies [39] | Specific target detection | Must be validated for IHC; check datasheets for recommended tissues |

| Isotype Controls [37] | Differentiate specific vs. nonspecific binding | Match subclass, concentration, and host species to primary antibody |

| Fab Fragment Blockers [41] | Block endogenous immunoglobulins | Critical for species-on-species staining; use at ~0.1 mg/mL |

| Directly Conjugated Primaries [40] | Eliminate secondary antibody background | Ideal for multiplexing; available with fluorophores (Coralite488, 594, 647) |

| Blocking Peptides [39] | Confirm antibody specificity | Pre-incubate antibody with peptide; should eliminate staining |

| Antigen Retrieval Buffers | Expose hidden epitopes | Citrate or Tris-EDTA depending on antibody requirements |

| Detection Systems | Visualize bound antibody | Consider enzyme-based (HRP/AP) vs. fluorescence based |

Figure 2: Comprehensive Control Implementation Strategy

Sourcing and selecting appropriate positive and negative control tissues is a fundamental requirement for valid IHC experiments. The optimal approach depends on multiple factors including antigen rarity, experimental system, and available resources. By implementing a comprehensive control strategy that includes properly sourced tissues, specialized controls for challenging scenarios, and adherence to validation guidelines, researchers can ensure their IHC results are reliable, reproducible, and scientifically valid. As technologies advance, particularly in AI-assisted quality control and standardized control materials, the field moves toward greater standardization and reliability in immunohistochemical analysis.

Optimal Placement and Staining of Control Slides

In immunohistochemistry (IHC), controls are not merely supplementary; they are fundamental components that validate the entire experimental process. They serve as critical internal checks that differentiate true positive signals from artefacts caused by nonspecific binding, autofluorescence, or protocol errors [42]. The integrity of IHC data, especially in drug development and diagnostic applications, hinges on the proper implementation and interpretation of these controls. Without appropriate controls, results may be unreliable, unreproducible, and ultimately misleading, potentially compromising scientific conclusions and clinical decisions.

The broader thesis of IHC control research emphasizes that controls are essential for confirming that observed staining patterns accurately reflect specific antibody-antigen interactions rather than procedural artefacts. Current research explores innovations in control materials and monitoring technologies, particularly the transition from traditional tissue-based controls to standardized cell line-derived controls and the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) for quality assessment [12] [13]. These advancements aim to address longstanding challenges in IHC, including the limited availability of certain tissue types, heterogeneity in control samples, and subjective visual assessment, thereby enhancing the reproducibility and reliability of IHC in both research and clinical settings.

Types of IHC Controls and Their Applications

Core Control Types for Validation

A robust IHC experiment incorporates multiple control types to address different potential sources of error. The table below summarizes the six essential IHC controls, their purposes, and implementation protocols.

Table 1: Essential Controls for IHC Experiments

| Control Type | Primary Purpose | Implementation Protocol | Interpretation of Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Tissue Control [42] [2] | Verify assay functionality and protocol optimization. | Stain a known antigen-expressing tissue alongside test samples using the identical protocol. | Valid Assay: Clear staining in control.Invalid Assay: No staining; indicates protocol failure. |

| Negative Tissue Control [42] [2] | Identify non-specific binding and false positives. | Use a tissue known not to express the target antigen. Knockdown/knockout samples are ideal [42]. | Specific Assay: No staining.Non-specificity: Staining indicates antibody or protocol issues. |

| No Primary Antibody Control [42] [2] | Detect nonspecific binding of the secondary antibody detection system. | Omit the primary antibody; incubate with antibody diluent only, then apply secondary antibody and detection reagents. | Clean System: No or minimal staining.Faulty System: Staining reveals secondary antibody cross-reactivity. |

| Isotype Control [42] [2] | Confirm staining specificity of monoclonal antibodies. | Replace primary antibody with a non-immune antibody of identical isotype, host species, and concentration. | Specific Staining: Signal in test sample distinct from isotype control.Non-specific Staining: Isotype control shows similar background. |

| Absorption Control [42] [2] | Demonstrate antibody binding is specific to the target antigen. | Pre-incubate primary antibody with excess purified immunogen (e.g., peptide) overnight, then use this mixture for staining. | Specific Binding: Significantly reduced or absent staining.Non-specific Binding: Staining persists, indicating off-target binding. |

| Endogenous Background Control [42] [2] | Identify inherent tissue properties that cause background signal. | Examine an unstained or secondary-antibody-only section under the microscope before running the full assay. | Low Background: Tissue suitable for assay.High Autofluorescence: Requires protocol adjustments (e.g., quenching). |

Novel Control Materials: Standardized Cell Lines and CLFs

Traditional patient tissue controls, while valuable, face challenges of limited availability, ethical issues, and inherent heterogeneity, which can lead to inconsistent expression levels from one control sample to the next [12] [13]. To address these limitations, researchers are increasingly adopting standardized alternatives:

- Standardized Cell Lines: Genetically engineered cell lines provide a consistent and renewable source for control material. Their use is particularly valuable for therapeutic protein targets like HER2 and PD-L1, as they offer more homogeneous antigen expression compared to traditional tissue blocks [12].

- Controls in Liquid Form (CLFs): These are cell suspensions prepared from genetically modified cell lines [13]. They can be applied manually via pipette or integrated into automated staining systems through a quality control module. CLFs form a regular circular shape with better cell distribution when applied automatically, and they faithfully mimic tissue controls by showing expected staining pattern changes under different antibody concentrations and antigen retrieval conditions [13].

Table 2: Comparison of Traditional vs. Novel Control Materials

| Feature | Traditional Tissue Controls | Standardized Cell Line Controls | Controls in Liquid Form (CLFs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Prior patient cases (normal or diseased tissue) [12] | Genetically modified cell lines [12] [13] | Genetically modified cell lines [13] |

| Availability | Limited, eventually run out [12] | Renewable, virtually unlimited | Renewable, virtually unlimited |

| Consistency | Heterogeneous, variable expression [12] | Homogeneous, constant expression | Homogeneous, constant expression |

| Application | Manual sectioning | Manual or automated | Optimized for automated systems [13] |

| Ethical Considerations | Involves patient material | Avoids patient material consumption | Avoids patient material consumption [13] |

Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

Quantitative Monitoring of Stain Variation

The implementation of standardized controls enables precise, AI-driven quality control. A 24-month longitudinal study monitoring HER2 and PD-L1 IHC staining of standardized cell lines using an AI algorithm (Qualitopix) revealed critical insights. The research quantified cell membrane expression levels weekly and identified multiple unexpected variations, particularly in low- and medium-expressing cell lines [12]. Further investigation traced these fluctuations to their root causes, identifying both inter-stainer variations (differences between the five autostainers used) and intra-run variations (differences between slide slots within the same stainer) [12].

This data underscores that staining variation is a real and quantifiable issue, even in controlled environments. The proactive response in this study—performing extra maintenance on a highly fluctuating stainer, which successfully reduced variation—demonstrates the practical value of a rigorous, data-driven QC process using standardized controls [12].

Diagnostic Performance of Automated Systems with Novel Controls

The diagnostic accuracy of IHC assays utilizing novel controls and automated systems has been validated in clinical research. A study of 87 lung adenocarcinoma specimens with known ALK status compared a novel automated system (LYNX480 PLUS with BP6165 antibody) against the established D5F3 antibody on the VENTANA platform [13]. The results, benchmarked against fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), demonstrate that the integrated system with its quality control approach delivers high performance.

Table 3: Diagnostic Performance of an Automated IHC System with Novel Controls for ALK Detection

| Parameter | BP6165 on LYNX480 PLUS Platform | Comparative Context |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 98.30% | Excellent, suitable for clinical screening |

| Specificity | 100% | Perfect specificity in this cohort |

| Sample Size (n) | 87 biopsy specimens | 47 ALK-positive, 40 ALK-negative |

| Reference Standard | Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) | Gold standard for ALK rearrangement |

| Control Method | Automated CLFs (ALK positive & negative) | Provides consistent quality monitoring [13] |

Protocols for Control Slide Placement and Staining

Workflow for Optimal Control Slide Integration

The following diagram illustrates the recommended workflow for integrating control slides into an automated IHC staining process, incorporating both traditional and novel control types to ensure comprehensive quality assurance.

Detailed Experimental Methodology

Protocol: Automated IHC Staining with Integrated CLF Controls for ALK Detection [13]

Slide Preparation:

- Cut 3-μm sections from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue blocks of test samples.

- For manual control placement, section positive and negative control tissue blocks. For automated placement, ensure target slides have space for CLF droplet application.

Application of Controls in Liquid Form (CLFs):

- Use the quality control module of the LYNX480 PLUS system.

- Scan the quick response (QR) code of the CLF vials (e.g., ALK positive CLF Catalog: BX30026P; ALK negative CLF Catalog: BX30026N).

- The system's automated pipetting system will dripped the corresponding CLFs onto the target slides.

- Dry and fix the applied CLF droplets onto the slide within minutes using the integrated heater.

Automated IHC Staining on LYNX480 PLUS:

- The staining module performs all subsequent steps:

- Deparaffinization and Rehydration: Standard protocols.

- Antigen Retrieval: Use EDTA retrieval solution (pH 9.0) for 60 minutes at 100°C.

- Peroxidase Blocking: Apply peroxidase blocking solution for 5 minutes.

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Incubate with anti-ALK antibody BP6165 (dilution 1:200) for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Detection: Incubate with post-primary antibody (15 min) and secondary antibody-HRP compound (20 min).

- Chromogenic Development: Apply diluted 3,3'-diaminobenzidine (DAB) for 10 minutes.

- Counterstaining: Counterstain with hematoxylin.

- Washing: Wash with buffer (TBS) or distilled water between steps as required.

- Dehydration and Coverslipping: Dehydrate and mount with coverslips.

Quality Assessment:

- For CLFs: The stained control droplets should show a regular circular shape and even cell distribution. The positive CLF should show specific cytoplasmic staining, while the negative CLF should show no staining.

- For the test tissue: ALK positivity is defined as tumor-specific cytoplasmic staining of any intensity superior to background in the vast majority of tumor cells.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and instruments essential for implementing high-quality IHC controls as discussed in the featured experiments and broader context.

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Tools for Advanced IHC Quality Control

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case/Product |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Control Cell Lines | Genetically engineered cell lines providing homogeneous, renewable source of control material for specific targets (e.g., HER2, PD-L1, ALK). | HER2 & PD-L1 controls for monitoring stainer performance [12]. |

| Controls in Liquid Form (CLFs) | Cell suspensions from modified lines applied manually or automatically to slides, saving tissue and ensuring consistency. | ALK Positive/Negative CLFs (e.g., Biolynx BX30026P/N) on LYNX480 PLUS [13]. |

| Automated IHC Stainer with QC Module | Instrument that automates staining and has a dedicated module for applying liquid controls via barcode scanning. | LYNX480 PLUS System with QC module [13]. |

| AI-Based Image Analysis Software | Algorithm that quantifies staining intensity and localization objectively, identifying variations invisible to the eye. | Qualitopix algorithm for monitoring stain quality over time [12]. |

| Validated Primary Antibodies | Antibodies optimized and validated for use on specific automated platforms with known performance characteristics. | BP6165 anti-ALK antibody on LYNX480 PLUS [13]. |

| Adhesion Microscope Slides | Slides with a chemical coating to prevent tissue loss during harsh IHC staining procedures, especially for tricky tissues. | KT5+ or TOMO slides with advanced adhesion [43]. |

| 4-Bromo-N-chlorobenzamide | 4-Bromo-N-chlorobenzamide, CAS:33341-65-0, MF:C7H5BrClNO, MW:234.48 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1,2-Dibromoanthracene | 1,2-Dibromoanthracene | 1,2-Dibromoanthracene is a high-purity reagent for materials science research. This product is For Research Use Only and not for human or veterinary use. |

Detailed Protocol for the No Primary Antibody Control

In the rigorous world of immunohistochemistry (IHC), controls are not merely suggestions but fundamental requirements for generating reliable and interpretable data. They form the bedrock of experimental validity, ensuring that the observed staining patterns accurately reflect the true localization and abundance of the target antigen. Within this ecosystem of controls, the No Primary Antibody Control stands as a critical negative control, specifically designed to identify false-positive results caused by the detection system itself [2] [44].

This guide places the No Primary Antibody Control within the broader context of IHC quality assurance, objectively comparing its application and value against other common negative controls. While positive controls verify that the IHC protocol can successfully detect the target antigen, negative controls like the No Primary Antibody Control are essential for confirming the specificity of the staining reaction [19]. By omitting the central reagent—the primary antibody—this control provides a baseline for non-specific background, enabling researchers to distinguish authentic signal from experimental artefact with greater confidence.

Theoretical Foundation of the No Primary Antibody Control

Purpose and Scientific Principle

The core function of the No Primary Antibody Control is to evaluate the specificity of the detection system and identify any non-specific binding contributed by the secondary antibody or other detection reagents [2] [28]. In a standard IHC workflow, the primary antibody binds specifically to the target epitope, and subsequent detection reagents then bind to the primary antibody to generate a visible signal. The No Primary Antibody Control tests the possibility that these detection reagents are themselves binding directly to tissue components, leading to a false-positive signal that could be misinterpreted as specific antigen expression [44].

The underlying principle is straightforward: if a visible stain appears in the No Primary Antibody Control slide, which has been processed identically to the test slide but without the primary antibody, it conclusively demonstrates that the staining is not due to specific primary antibody-epitope interaction [28]. A valid result for this control is negligible or absent staining that does not resemble the specific pattern observed in the test section [2] [28].

Position in the IHC Control Ecosystem