Overcoming the Signal Challenge: A Comprehensive Guide to Immunostaining Low Abundance Protein Targets

Detecting low abundance proteins via immunostaining presents significant challenges in protein localization and biomarker research, often hindered by high background noise and weak specific signals.

Overcoming the Signal Challenge: A Comprehensive Guide to Immunostaining Low Abundance Protein Targets

Abstract

Detecting low abundance proteins via immunostaining presents significant challenges in protein localization and biomarker research, often hindered by high background noise and weak specific signals. This article provides a systematic guide for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of immunostaining and the unique obstacles posed by low abundance targets. It details advanced methodological strategies for sample preparation, signal amplification, and enrichment techniques. A dedicated troubleshooting section addresses common pitfalls like high background and autofluorescence, while the final segment focuses on rigorous experimental validation and comparative analysis of detection platforms to ensure reliable and reproducible results.

The Low Abundance Challenge: Understanding the Fundamentals of Immunostaining and Signal-to-Noise Dynamics

Immunostaining is a foundational technique in biological research and clinical diagnostics that utilizes the specific binding of antibodies to target antigens within cells and tissues, allowing for the visualization of their presence, localization, and abundance [1]. For researchers focusing on low-abundance protein targets—such as certain cytokine receptors, signaling molecules, or proteins in limited sample volumes—the choice of immunostaining method is critical [2]. The core decision often centers on whether to use a direct or indirect detection method, as this choice fundamentally impacts the sensitivity, specificity, and overall success of the experiment [1] [3]. This application note details the principles of these methods, provides structured comparisons and optimized protocols for detecting low-abundance targets, and outlines advanced signal amplification strategies essential for reliable results in drug development and basic research.

Core Principles and Methodological Comparison

The principle of immunostaining is based on the specific interaction between an antibody and its target antigen. To visualize this interaction, the antibody is conjugated to a detectable marker, such as a fluorescent dye or an enzyme [1].

Direct Immunostaining

The direct method uses a single primary antibody that is directly conjugated to a detectable marker (e.g., a fluorophore or enzyme). This antibody binds specifically to the target antigen in a one-step incubation process [1] [3].

Advantages:

- Speed: The protocol is faster due to fewer incubation and washing steps [1].

- Simplicity: Reduced complexity minimizes potential sources of error [4].

- Multiplexing: Allows for easier simultaneous detection of multiple targets from different species without cross-reactivity [3].

- Background: Lower potential for background signal from secondary antibody cross-reactivity [3] [4].

Disadvantages:

- Sensitivity: Lower sensitivity because signal amplification is absent [1] [4].

- Flexibility: Limited availability of commercially available conjugated primary antibodies, and each must be purchased pre-conjugated [1] [4].

- Signal: The signal may be weak for low-abundance targets [5].

Indirect Immunostaining

The indirect method uses an unlabeled primary antibody that binds to the antigen. Then, a labeled secondary antibody, which recognizes and binds to the primary antibody, is applied. Multiple secondary antibodies can bind to a single primary antibody, amplifying the signal [1] [3].

Advantages:

- Sensitivity: Significantly higher sensitivity due to signal amplification [1] [4]. This makes it the preferred choice for low-abundance targets [5].

- Flexibility: A wide range of labeled secondary antibodies are available, and the same secondary antibody can be used with different primary antibodies from the same host species [1].

- Cost-Effectiveness: Secondary antibodies are often less expensive than conjugating every primary antibody [3].

Disadvantages:

- Time: The protocol is longer due to the additional incubation and washing steps [1].

- Background: Higher potential for background signal due to non-specific binding of the secondary antibody [3] [4].

- Cross-Reactivity: Requires careful selection of primary and secondary antibodies from different species to avoid aberrant crosslinking [1] [3].

Quantitative Comparison of Direct vs. Indirect Methods

The table below summarizes the key differences between the two methods to aid in selection.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Direct and Indirect Immunostaining Methods

| Feature | Direct Method | Indirect Method |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Antibody | Conjugated with a detectable marker [1] | Unlabeled; specific to the target antigen [1] |

| Secondary Antibody | Not required [1] | Conjugated; binds to the primary antibody [1] |

| Processing Time | Fast (one-step incubation) [1] | Slow (two-step incubation) [1] |

| Sensitivity | Low [1] [4] | High (signal amplification) [1] [4] |

| Signal Amplification | No [1] | Yes [1] |

| Multiplexing Potential | Easier with antibodies from different hosts [3] | More complex, requires careful host species selection [3] |

| Commercial Availability | Limited conjugated primary antibodies [1] | Many secondary antibody options available [1] |

| Background Signal | Lower (fewer non-specific binding sites) [3] | Higher (potential for secondary cross-reactivity) [3] |

| Best Suited For | High-abundance targets [5] | Low- and medium-abundance targets [5] |

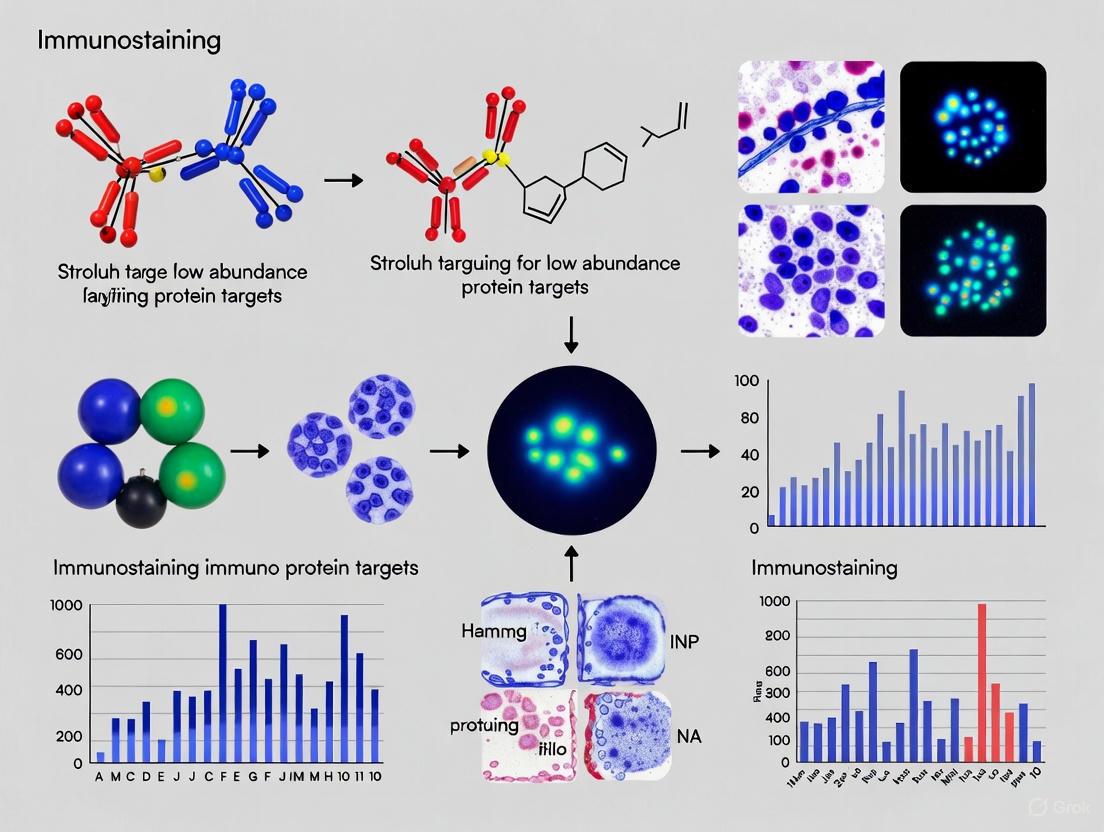

The following workflow diagram illustrates the core components and procedural differences between direct and indirect immunostaining.

Diagram 1: Immunostaining Method Workflow and Outcomes. This chart compares the steps and key characteristics of direct (green) and indirect (blue) immunostaining methods.

Advanced Strategies for Low-Abundance Targets

For low-abundance proteins, which can be present at fewer than 2000 molecules per cell [2], the standard indirect method may be insufficient. Further signal amplification is often required.

Signal Amplification Beyond the Secondary Antibody

Advanced techniques introduce additional layers to the staining protocol to dramatically increase the number of fluorophores deposited at the target site.

- Biotin-Streptavidin Amplification: This is a highly effective three-step method. After the primary antibody is applied, a biotinylated secondary antibody is used, followed by streptavidin conjugated to a bright fluorophore like phycoerythrin (PE) or Alexa Fluor dyes [2]. Streptavidin has a very high affinity for biotin, and multiple fluorophores can be conjugated to a single streptavidin molecule. Sensitivity can be pushed even further by adding a fourth layer (e.g., anti-PE antibody) and a fifth layer (PE-streptavidin) [2].

- Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA): This is an enzyme-mediated method. An HRP-conjugated secondary antibody catalyzes the deposition of numerous labeled tyramide molecules at the antigen site. This technique provides exceptional sensitivity for detecting targets that are otherwise undetectable [5].

Reagent Selection for Varying Target Abundance

The table below outlines optimal reagent choices based on the abundance level of your target protein.

Table 2: Reagent Selection Guide for Target Abundance Levels

| Target Abundance | Primary Antibody | Secondary Detection | Advanced Amplification |

|---|---|---|---|

| High (e.g., Tubulin) | Conjugated primary [5] | Standard conjugated secondary [5] | Usually not required; may cause over-amplification [5] |

| Medium (e.g., Golgi proteins) | Unlabeled primary [5] | Standard conjugated secondary or streptavidin-biotin [5] | May be beneficial for quantification [5] |

| Low (e.g., Cytokine receptors) | Unlabeled primary [5] | High-sensitivity fluorophores (e.g., PE, Alexa Fluor dyes) [2] | Essential (e.g., multi-layer biotin-streptavidin or tyramide amplification) [2] [5] |

The following diagram visualizes the layered approach of a high-sensitivity amplification strategy.

Diagram 2: High-Sensitivity Detection with Biotin-Streptavidin Amplification. This multi-layer method significantly increases the signal for low-abundance targets.

Optimized Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Standard Indirect Immunofluorescence for Cultured Cells

This protocol is optimized for detecting medium-abundance targets and forms the base for further amplification [1] [5].

- Cell Seeding and Fixation: Seed cells on coverslips. At the desired confluence, fix cells with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at room temperature.

- Permeabilization and Blocking: Permeabilize cells with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes. Incubate with a blocking buffer (e.g., 5% normal serum from the secondary antibody host species or 1% BSA in PBS) for 1 hour to prevent non-specific binding [1] [6].

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Apply the optimized concentration of primary antibody diluted in blocking buffer. Incubate in a humidified chamber for 1 hour at room temperature or overnight at 4°C.

- Washing: Wash the coverslip 3 times for 5 minutes each with wash buffer (e.g., PBS with 0.05% Tween-20) to remove unbound antibody [1].

- Secondary Antibody Incubation: Apply the fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody, specific to the host species of the primary antibody, diluted in blocking buffer. Incubate for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark.

- Washing and Mounting: Wash 3 times for 5 minutes in the dark. Counterstain nuclei with DAPI if desired. Mount coverslips using an antifade mounting medium (e.g., VECTASHIELD) to reduce photobleaching [1].

Protocol: Enhanced Detection for Low-Abundance Targets

This protocol modifies the standard indirect method by incorporating biotin-streptavidin amplification [2].

- Steps 1-4: Follow the standard protocol for fixation, blocking, primary antibody incubation, and washing.

- Biotinylated Secondary Antibody: Incubate with a biotinylated secondary antibody (e.g., biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG) diluted in blocking buffer for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Washing: Wash 3 times for 5 minutes.

- Fluorophore-Streptavidin Incubation: Incubate with a bright fluorophore-conjugated streptavidin (e.g., PE or Alexa Fluor 647) diluted in an appropriate buffer for 30 minutes at room temperature in the dark [2].

- Steps 6-7: Complete the protocol with final washes, counterstaining, and mounting as described in the standard protocol.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Immunostaining

| Item | Function | Key Considerations for Low-Abundance Targets |

|---|---|---|

| High-Specificity Primary Antibodies | Binds specifically to the target protein. | Use monoclonal or recombinant antibodies for consistency. Knock-out (KO) validation is crucial to confirm specificity and avoid false positives [4] [7]. |

| Biotinylated Secondary Antibodies | Serves as a link for subsequent amplification in indirect staining. | Multiple molecules can bind to a single primary antibody, providing the first level of signal amplification [2]. |

| Bright Fluorophores | The detectable label that emits light upon excitation. | For low-abundance targets, select fluorophores with high extinction coefficients and quantum yields (e.g., Phycoerythrin (PE), Alexa Fluor 647) [2]. |

| Fluorophore-Conjugated Streptavidin | Binds with high affinity to biotin on the secondary antibody. | A single streptavidin molecule can be conjugated to multiple fluorophores, providing a second level of signal amplification [2] [5]. |

| Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA) Kits | Enzyme-mediated system that deposits numerous fluorophores at the target site. | Provides extremely high sensitivity for detecting otherwise undetectable targets [5]. |

| Antifade Mounting Media | Preserves the fluorescence signal during storage and imaging. | Protects against photobleaching, which is critical when using high laser power or long exposure times for weak signals [1]. |

| Autofluorescence Quenchers | Reduces naturally occurring background fluorescence from tissue components. | Reagents like Vector TrueVIEW or Sudan Black B increase the signal-to-noise ratio, making weak specific signals easier to distinguish [6]. |

| 24,25-Epoxytirucall-7-en-3,23-dione | 24,25-Epoxytirucall-7-en-3,23-dione, MF:C30H46O3, MW:454.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pinocembrin, 7-acetate | Pinocembrin, 7-acetate, MF:C17H14O5, MW:298.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The strategic selection between direct and indirect immunostaining methods is paramount, with the indirect method being the cornerstone for sensitive detection of low-abundance proteins due to its inherent signal amplification. For the most challenging targets, moving beyond the standard indirect protocol to incorporate advanced amplification strategies—such as biotin-streptavidin systems or tyramide signal amplification—is not just beneficial but essential. By combining these powerful methods with rigorous antibody validation, meticulous protocol optimization, and the use of high-sensitivity reagents, researchers can reliably uncover the localization and expression of critical low-abundance protein targets, thereby advancing both basic research and drug development efforts.

The detection of low-abundance proteins (LAPs) is a fundamental challenge in modern biological research and drug development. These proteins, which include key signaling molecules, transcription factors, and receptors, often play critical roles in cellular processes despite their scarce quantities [8]. The central obstacle in their study is the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR)—the strength of the specific detection signal relative to the surrounding non-specific background interference. In proteomics, the dynamic concentration range of proteins can span an estimated 12-15 orders of magnitude, meaning high-abundance proteins can be present in concentrations millions of times greater than low-abundance species [9]. This vast disparity means that the signals from LAPs are often obscured, making their accurate detection and quantification exceptionally difficult. This application note details the sources of this critical challenge and provides validated protocols to enhance SNR for successful LAP detection in immunostaining applications.

The Signal-to-Noise Bottleneck in Protein Detection

The difficulty in detecting LAPs stems from several interconnected factors that collectively degrade the SNR.

Fundamental Physical and Technical Limitations

The cellular abundance of a protein is directly linked to its function. Signaling proteins like kinases and transcription factors are typically low-abundance, often constituting less than 1,000 copies per cell [8]. In a typical sample, the total protein mass is dominated by a few high-abundance proteins (e.g., albumin in serum, RuBisCO in plants), which can mask the detection signals of LAPs [9]. Furthermore, most analytical methods, including immunoassays, have a limited dynamic range of 4-5 orders of magnitude, which is insufficient to cover the full range of protein concentrations in a biological sample [9].

A high background signal, or "noise," is a primary contributor to poor SNR. Key sources of this noise include:

- Autofluorescence: Caused by endogenous molecules in cells and tissues, which fluoresce under the same wavelengths used for detection [3] [10].

- Unspecific Antibody Binding: Antibodies binding non-specifically to non-target proteins or the solid support (e.g., the membrane in Western blotting) [3] [11].

- Incomplete Transfer: In Western blotting, inefficient transfer of proteins from the gel to the membrane leads to a weak target signal [12].

- Masked Epitopes: Chemical fixation can crosslink proteins and mask the antigenic sites recognized by antibodies, reducing the specific signal [3].

The following table summarizes the major challenges and their impact on the signal-to-noise ratio.

Table 1: Key Challenges in Low-Abundance Protein Detection and Their Impact on Signal-to-Noise Ratio

| Challenge | Impact on Signal | Impact on Noise | Overall Effect on SNR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Massive Dynamic Range [9] | LAP signal is obscured by high-abundance proteins | High-abundance proteins contribute to non-specific background | Drastic Reduction |

| Limited Method Dynamic Range [9] | LAP concentrations fall below detection limits | Saturation from high-abundance proteins increases background | Reduction |

| Antibody Specificity [12] [3] | Reduced by cross-reactivity and masked epitopes | Increased due to non-specific binding | Reduction |

| Sample Autofluorescence [3] [10] | No direct impact | Significant increase in background fluorescence | Reduction |

| Inefficient Transfer (WB) [12] | Significant reduction of target protein on membrane | No direct impact | Reduction |

Methodologies for SNR Enhancement: Application Notes and Protocols

Protocol: Enhanced Immunofluorescence with a Low-Cost Antibody Signal Enhancer (ASE)

This protocol, adapted from Rosas-Arellano et al. (2020), uses a simple, low-cost solution to significantly improve the SNR in immunostaining procedures for LAPs [10].

1. Principle The ASE solution works through multiple mechanisms: glycine competes with free aldehydes from fixation to prevent them from binding antibodies and epitopes; hydrogen peroxide quenches autofluorescence; and a mixture of non-ionic detergents (Triton X-100 and Tween-20) provides synergistic membrane permeabilization [10].

2. Reagents and Solutions

- Prepare ASE Solution: 0.75% glycine, 0.075% hydrogen peroxide, 0.04% Triton X-100, 0.03% Tween-20 in your standard buffer (e.g., PBS).

- Standard blocking solution (e.g., 1-5% BSA or serum in PBS).

- Primary antibody dilution buffer (typically 1% BSA in PBS).

- Primary and secondary antibodies.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Sample Preparation: Follow standard procedures for cell culture, tissue fixation, and permeabilization.

- Blocking: Prepare a blocking solution by mixing 2/3 of your standard blocking solution with 1/3 of the ASE solution. Incubate the samples with this mixture for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Dilute the primary antibody in a solution composed of 2/3 standard antibody dilution buffer and 1/3 ASE solution. Incubate with the samples overnight at 4°C.

- Washing: Wash the samples 3 times for 5 minutes each with a wash buffer that contains 0.01% Tween-20.

- Secondary Antibody Incubation: Incubate with the fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody (diluted in standard dilution buffer without ASE) for 1 hour at room temperature, protected from light.

- Final Wash and Mounting: Perform final washes and mount the samples for microscopy.

4. Key Applications and Validation

- This method has been validated in cell culture, primate brain tissue, and human cancer biopsies [10].

- It is compatible with immunohistofluorescence and can be combined with other protocols, such as the "SIP" (Sequential Incubation Process) for multiple labeling [10].

- The ASE can allow for the use of higher antibody dilutions, conserving precious reagents.

Protocol: Optimizing Western Blotting for Low-Abundance Proteins

This protocol consolidates best practices for maximizing SNR when detecting LAPs via Western blot [12] [11].

1. Efficient Protein Extraction and Transfer

- Lysis Buffer: For proteins in specific compartments (e.g., nucleus, mitochondria), use a harsh lysis buffer like RIPA (containing SDS) to ensure complete lysis, or use subcellular fractionation kits to enrich for your target [11].

- Gel Chemistry: Choose the appropriate gel for optimal separation. Use Bis-Tris gels (6-250 kDa) for general use, Tris-Acetate gels (40-500 kDa) for high molecular weight proteins, and Tricine gels (2.5-40 kDa) for low molecular weight proteins [12].

- Membrane and Transfer: Use PVDF membrane for its higher protein binding capacity and lower non-specific binding compared to nitrocellulose. For efficient transfer, consider dry electroblotting systems to minimize handling inconsistencies and improve transfer reproducibility, especially for high molecular weight proteins [12].

2. Antibody and Detection Optimization

- Antibody Validation: Use antibodies that are knockdown/knockout (KD/KO) validated to ensure specificity for the target protein [11].

- Antibody Titration: When using high-sensitivity substrates, reduce the concentration of primary and secondary antibodies to prevent high background from HRP overloading. Follow manufacturer recommendations for dilution factors [11].

- Enhanced Chemiluminescence (ECL): Use high-sensitivity ECL substrates (e.g., SuperSignal West Atto, SignalBright series) capable of detecting down to the attogram to femtogram level. These substrates provide a brighter signal and a higher SNR than conventional ECL [12] [11].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SNR Enhancement

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Combinatorial Peptide Ligand Libraries (CPLLs) [9] | Equalize protein concentrations by reducing high-abundance proteins and enriching low-abundance proteins. | Pre-processing of complex samples like serum or cell lysates for proteomic analysis. |

| High-Sensitivity ECL Substrates [12] [11] | Amplify the light output from the HRP enzyme, enabling detection of very low levels of protein. | Western blot detection of low-copy-number signaling proteins. |

| KD/KO Validated Antibodies [11] | Ensure the antibody binds specifically to the target protein, minimizing off-target signal (noise). | Any immunodetection application (WB, IF) where specificity is critical. |

| Antibody Signal Enhancer (ASE) [10] | A low-cost additive to block and antibody solutions that reduces background and amplifies specific signal. | Immunofluorescence and immunocytochemistry on fixed cells and tissues. |

| Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA) [13] | An enzyme-mediated method that deposits multiple fluorophore labels at the target site, dramatically amplifying signal. | Detecting low-abundance targets in immunofluorescence, particularly for 3D pathology. |

Visualizing the Signal-to-Noise Challenge and Solutions

The following diagram illustrates the core problem of SNR and the primary strategic approaches to overcoming it.

The critical role of the signal-to-noise ratio in the detection of low-abundance proteins cannot be overstated. The difficulty is inherent in the vast dynamic range of proteomes and the technical limitations of our detection methods. However, as detailed in these application notes, a systematic approach that combines sample preparation optimization, reagent validation, and signal amplification strategies can successfully tilt the balance in favor of a detectable signal. By implementing protocols such as the Antibody Signal Enhancer for immunostaining and rigorous optimization for Western blotting, researchers can overcome these hurdles to illuminate the previously invisible world of low-abundance proteins, thereby advancing our understanding of cellular mechanisms and drug discovery.

Common Pitfalls in Sample Preparation That Obscure Low Abundance Targets

The detection of low-abundance proteins via immunostaining techniques such as Western blotting and immunohistochemistry (IHC) presents a significant challenge in biomedical research and drug development. These targets, which include rare biomarkers, signaling molecules, and transcription factors, are often obscured by inadequate sample preparation methods that fail to preserve, extract, and detect limited protein quantities. In the context of immunostaining research, where the visual output depends entirely on target preservation and accessibility, optimization of sample preparation is not merely beneficial but essential for generating reproducible and scientifically valid data. This application note details common pitfalls throughout the sample preparation workflow and provides optimized protocols to overcome these challenges, enabling reliable detection of low-abundance targets for critical research applications.

Critical Pitfalls and Optimized Solutions

Protein Extraction and Enrichment

Pitfall: Inefficient extraction leading to inadequate protein yield Inefficient lysis and extraction represent the first major point of failure for low-abundance targets. Standard lysis buffers may fail to completely disrupt cellular compartments, particularly for nuclear, membrane-bound, or cytoskeletal proteins, resulting in insufficient target protein in the final lysate.

Solutions:

- Localization-specific extraction: Use optimized buffers specific to your target's cellular location. Harsher detergents like RIPA buffer (containing SDS) are recommended for complete lysis of intracellular compartments, including the nuclear envelope [14] [15]. For particularly challenging localized proteins, consider subcellular fractionation kits to enrich nuclear or membrane components, thereby increasing the relative concentration of your target [14] [15].

- Inhibition of degradation: Add broad-spectrum protease and phosphatase inhibitors immediately to the lysis buffer to protect vulnerable epitopes and prevent degradation of already scarce targets [12] [14]. For phosphorylation studies, this is particularly critical.

- Mechanical disruption: Employ ultrasonication to ensure complete disruption of all cellular clusters and facilitate the release of nuclear proteins. A typical protocol involves 3-second pulses with 10-second intervals, repeated 5-15 times at 40 kW power [14].

- Inhibition of secretion: For secreted proteins, add Brefeldin A (BFA) to cell cultures before harvesting to prevent target protein secretion into the extracellular space, thereby ensuring sufficient protein remains detectable in the whole cell lysate [14] [16].

Table 1: Recommended Extraction Methods Based on Protein Localization

| Protein Localization | Recommended Lysis Buffer | Additional Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| Nuclear | RIPA with SDS | Ultrasonication, nuclear fractionation kits |

| Membrane-bound | RIPA with SDS | Membrane fractionation kits |

| Cytoplasmic | Standard lysis buffers | Mechanical homogenization |

| Secreted | Standard lysis buffers | Brefeldin A treatment pre-harvest |

| Multiple compartments | RIPA with SDS | Subcellular fractionation |

Gel Electrophoresis and Transfer

Pitfall: Poor resolution and transfer efficiency Even with successful extraction, inadequate separation during gel electrophoresis or inefficient transfer to membrane can prevent antibody access to low-abundance targets, resulting in weak or non-detectable signals.

Solutions:

- Gel chemistry selection: Choose gel chemistry based on your target protein size. Bis-Tris gels (6-250 kDa) with neutral pH preserve protein integrity and provide better band resolution than traditional Tris-glycine gels. For high molecular weight proteins (>300 kDa), Tris-Acetate gels provide superior separation, while Tricine gels are ideal for low molecular weight proteins (<40 kDa) [12] [14].

- Increased sample loading: Load 50-100 μg of total protein per lane to enhance target protein quantity. Using gels with 1.5 mm combs instead of 1.0 mm increases well capacity, allowing for higher sample volumes without compromising separation [14].

- Optimal transfer methods: For high molecular weight targets, extend transfer times and consider higher voltages. PVDF membranes are preferred over nitrocellulose for their higher protein binding capacity and lower non-specific antibody binding, which reduces background [14] [15]. Ensure PVDF membranes are pre-wetted in methanol before transfer [14] [16].

- Transfer verification: Stain membranes with Ponceau S post-transfer to confirm efficient and uniform protein migration from gel to membrane [14] [16].

Antibody Selection and Validation

Pitfall: Non-specific or insensitive detection The use of non-validated antibodies or inappropriate concentrations represents one of the most common failures in low-abundance target detection, leading to high background, false positives, or complete absence of signal.

Solutions:

- Antibody validation: Select antibodies specifically validated for your application (Western blot, IHC, IF) and ideally verified using knockout/knockdown controls to confirm specificity. Recombinant monoclonal antibodies are recommended for superior specificity and batch-to-batch consistency [4].

- Antibody concentration optimization: While higher primary antibody concentrations are often necessary for low-abundance targets, excessive concentrations can increase background. Follow manufacturer recommendations and perform gradient testing to determine optimal dilution [14] [16]. When using high-sensitivity substrates, secondary antibody concentrations may need reduction to prevent background [15].

- Detection method selection: For maximum sensitivity, use indirect detection methods with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and high-sensitivity chemiluminescent substrates, which provide significant signal amplification over direct detection methods or fluorescent systems [4] [15].

Table 2: Antibody and Detection Optimization for Low-Abundance Targets

| Parameter | Standard Approach | Optimized for Low-Abundance Targets |

|---|---|---|

| Antibody Validation | Application-specific | Knockout/Knockdown validated |

| Antibody Clonality | Polyclonal or monoclonal | Recombinant monoclonal |

| Detection Method | Direct or standard indirect | Indirect with signal amplification |

| Secondary Antibody | Standard HRP-conjugated | HRP-conjugated with high-sensitivity substrates |

| Signal Detection | Standard ECL or fluorescence | Enhanced chemiluminescence (e.g., SuperSignal West Atto, SignalBright) |

Tissue Preparation for IHC/IF

Pitfall: Epitope masking and poor morphology In immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence, improper tissue fixation and processing can mask epitopes through cross-linking or destroy tissue morphology, making it impossible to localize low-abundance targets accurately.

Solutions:

- Fixation optimization: For FFPE tissues, ensure consistent fixation times to prevent over-fixation which causes excessive cross-linking and epitope masking, or under-fixation which compromises morphology [17] [18].

- Antigen retrieval: Employ optimized antigen retrieval methods based on your target epitope. Pressure-boiling slides in acidic citrate buffer (pH 6) for 15-20 minutes is common, though some nuclear targets may require high-pH retrieval solutions [17].

- Multiplex IHC considerations: For multiplex fluorescent IHC, carefully optimize antibody concentrations using conventional IHC first, then apply to multiplex protocols with sequential antibody application, HRP-based tyramide signal amplification, and heat-mediated antibody stripping between rounds [19].

Complete Workflow for Low-Abundance Protein Detection

Enhanced Detection System for Low-Abundance Targets

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Low-Abundance Targets

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Low-Abundance Detection |

|---|---|---|

| Protease Inhibitors | Broad-spectrum protease inhibitor cocktails | Protect vulnerable low-abundance targets from degradation during extraction [12] [14] |

| Enhanced Lysis Buffers | RIPA buffer with SDS | Complete disruption of cellular compartments for efficient protein recovery [14] [15] |

| Specialized Gels | Bis-Tris, Tris-Acetate, Tricine gels | Optimal separation based on protein size for improved resolution [12] [14] |

| High-Binding Capacity Membranes | PVDF membranes | Increased protein binding with reduced background compared to nitrocellulose [14] [15] |

| Validated Antibodies | Knockout/knockdown validated antibodies | Specific confirmation of target recognition with minimal off-target binding [4] [15] |

| High-Sensitivity Substrates | SuperSignal West Atto, SignalBright series | Enhanced chemiluminescent detection capable of attogram to femtogram sensitivity [12] [15] |

| Antigen Retrieval Reagents | Citrate buffer (pH 6), EDTA buffer (pH 9) | Unmasking of epitopes cross-linked during tissue fixation [17] |

| 4E-Deacetylchromolaenide 4'-O-acetate | 4E-Deacetylchromolaenide 4'-O-acetate, MF:C22H28O7, MW:404.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Isoorientin-7-O-[6-sinapoyl]-glucoside | Isoorientin-7-O-[6-sinapoyl]-glucoside, MF:C38H40O20, MW:816.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Successful detection of low-abundance protein targets requires a holistic approach to sample preparation that addresses multiple potential failure points across the entire workflow. By implementing these optimized protocols—from targeted protein extraction and appropriate separation chemistries to validated antibodies and enhanced detection systems—researchers can significantly improve their capability to visualize and quantify scarce targets. These methods provide a foundation for reliable investigation of low-abundance proteins, enabling advances in biomarker discovery, drug development, and fundamental biological research where sensitivity and specificity are paramount.

The detection and accurate quantification of low-abundance proteins are critical for advancing biomedical research, particularly in the discovery of biomarkers for diseases such as cancer. However, the immense dynamic range of protein concentrations in biological samples presents a significant analytical challenge. In blood serum or plasma, for instance, high-abundance proteins (HAPs) like albumin and immunoglobulins can constitute over 90% of the total protein mass, while potential biomarker proteins may exist at concentrations several orders of magnitude lower [20] [21]. This disparity allows HAPs to dominate analytical signals, effectively masking the detection of rare, low-abundance targets [20]. This application note delineates the core problems posed by HAPs, evaluates current solutions with structured data, and provides detailed protocols for researchers engaged in immunostaining and proteomic analysis of low-abundance protein targets.

Mechanisms of Interference and Masking

The domination of HAPs manifests through several technical mechanisms that compromise assay sensitivity and specificity.

- Ion Suppression in Mass Spectrometry: In LC-MS/MS analysis, the co-elution of highly abundant peptides from HAPs can suppress the ionization of peptides from low-abundance proteins, rendering them undetectable [20] [21].

- Resource Sequestration: HAPs compete for and deplete reagents, such as enzymes (e.g., trypsin), antibodies, and fluorescent tags, during sample processing and staining, leaving limited capacity for the detection of low-abundance targets [3].

- Increased Background Noise: Non-specific binding of antibodies to HAPs or to surfaces saturated with HAPs elevates background signal, which drastically reduces the signal-to-noise ratio critical for visualizing low-abundance proteins [3] [22].

- Spatial Occlusion: In tissue imaging, dense regions of HAPs can physically block antibody access to epitopes on less abundant targets, leading to false negatives [3].

The following diagram illustrates the core problem and the two principal strategic approaches to resolve it.

Quantitative Assessment of Depletion and Amplification Strategies

Comparative Performance of Depletion Techniques

A cross-species proteomic study evaluated several depletion methods for their efficiency, protein identification capability, and cost-effectiveness. The table below summarizes the key findings, which are critical for selecting an appropriate method for your experimental setup [21].

Table 1: Performance comparison of high-abundance protein (HAP) depletion methods across different animal sera.

| Depletion Method | Working Mechanism | Depletion Efficiency (Rank) | Protein Identification (Rank) | Cost-Effectiveness (USD/sample) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minute Kit | Solubility-based (dissolves HAPs, precipitates low-abundance proteins) | 1 | 2 | ~$11 - $136 |

| Norgen Kit | Ion Exchange Chromatography | 2 | 1 | >$20 (more expensive than PerCA) |

| PerCA Precipitation | Acid-based Precipitation (Perchloric Acid) | 3 | 3 | ~$5 (>20x cheaper than kits) |

| Thermo Kit | Immunoaffinity (Anti-Albumin) | 4 | 4 | Most expensive among kits |

Advanced Signal Amplification Technologies

For techniques like western blot, immunofluorescence, and mass cytometry, signal amplification is often necessary to detect low-abundance proteins. The following table compares several advanced amplification methods [22] [23].

Table 2: Comparison of advanced signal amplification technologies for detecting low-abundance proteins.

| Technology | Principle | Key Feature | Reported Signal Increase | Multiplexing Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE (Amplification by Cyclic Extension) | Thermal-cycling-based DNA concatenation with photocrosslinking | High thermal stability; suitable for mass cytometry | >500-fold | High (>30 targets) |

| Immuno-SABER | Presynthesized DNA concatemer hybridization | Originally developed for imaging | Not quantified for mass cytometry | High (tens of targets) |

| Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA) | Enzyme-catalyzed deposition of tyramide | High sensitivity | High (often >100x) | Low (limited by enzyme use) |

| Enhanced Chemiluminescence (e.g., SignalBright) | Enhanced chemiluminescent substrates for HRP | Detects femtogram levels of protein | High vs. standard ECL | Compatible with standard WB |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Immunoaffinity Depletion of Serum/Plasma HAPs

This protocol is adapted for a standard immunoaffinity depletion column (e.g., MARS, Seppro) [20].

Materials:

- Immunoaffinity depletion column specific to target species HAPs.

- Equilibrium Buffer (as recommended by column manufacturer).

- Serum or plasma sample.

- Low-protein binding microcentrifuge tubes.

Procedure:

- Equilibration: Condition the immunoaffinity column with 5-10 column volumes of Equilibrium Buffer at 4°C.

- Sample Preparation: Centrifuge the serum/plasma sample at 15,000 × g for 10 minutes to remove any precipitates or lipids. Dilute the supernatant as per the manufacturer's instructions (typically 1:5 in Equilibrium Buffer).

- Depletion: Load the diluted sample onto the pre-equilibrated column. Collect the flow-through, which contains the HAP-depleted serum/plasma.

- Wash: Wash the column with 2-3 column volumes of Equilibrium Buffer, pooling the wash fractions with the initial flow-through.

- Concentration and Buffer Exchange: Concentrate the pooled HAP-depleted sample using a centrifugal filter unit (e.g., 10 kDa MWCO) and exchange the buffer into one compatible with downstream analysis (e.g., PBS or MS-compatible buffer).

- Regeneration and Storage: Regenerate the column according to the manufacturer's instructions for future use.

Protocol 2: ACE Signal Amplification for Mass Cytometry

This protocol enables high-sensitivity detection of low-abundance epitopes in single-cell mass cytometry [23].

Materials:

- Antibodies conjugated to short DNA initiator oligonucleotides (TT-a, 11-mer).

- Bst DNA Polymerase (Large Fragment).

- Extender oligonucleotide (a-T-a, 19-mer).

- Deoxynucleotide solution (dNTPs).

- Detector oligonucleotides with CNVK photocrosslinker, conjugated to metal-cheating polymers (e.g., DTPA-Ln3+).

- UV lamp (365 nm).

Procedure:

- Staining: Stain cell suspensions (for surface or intracellular markers) with the initiator-conjugated antibody cocktail. Wash to remove unbound antibodies.

- Cyclic Extension Reaction:

- Prepare the extension master mix containing Bst polymerase, dNTPs, and the extender oligonucleotide.

- Resuspend the stained cells in the extension master mix.

- Perform thermal cycling (20-500 cycles): Denature at 58°C for 1 minute, Extend at 22°C for 1 minute.

- This cycle elongates the initiator strand, creating hundreds of repeats of the detector binding site.

- Metal Detector Hybridization: Hybridize the metal-conjugated, CNVK-modified detector oligonucleotides to the extended initiator strands on the cells. Incubate for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Photocrosslinking: Expose the cell suspension to UV light (365 nm) for 1 second to covalently crosslink the detector strands to the extended initiator. This step is critical for stability during mass cytometry acquisition.

- Acquisition: Wash cells and acquire data on a mass cytometer. The stabilized amplification complex survives the high-temperature vaporization step.

The workflow for the ACE protocol is detailed below.

Protocol 3: Optimized Western Blotting for Low-Abundance Proteins

This protocol focuses on maximizing the signal from low-abundance targets in western blot [22].

Materials:

- RIPA Lysis Buffer (or other appropriate, harsh lysis buffer for efficient extraction).

- PVDF Membrane (higher protein binding capacity than nitrocellulose).

- High-Sensitivity Chemiluminescent Substrate (e.g., SignalBright Pro, Plus, or Max).

- Knockout/Knockdown validated primary antibodies.

- HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies.

Procedure:

- Protein Extraction: Use a harsh lysis buffer like RIPA (containing SDS) to ensure efficient extraction of proteins from all cellular compartments, including the nucleus. For particularly difficult targets, consider using subcellular fractionation kits prior to lysis.

- Gel Electrophoresis and Transfer: Perform standard SDS-PAGE. For transfer to membrane, optimize conditions for your target protein's molecular weight. Use PVDF membrane due to its high binding capacity and low non-specific antibody binding. Ensure complete transfer to prevent signal loss.

- Blocking and Antibody Incubation:

- Block the membrane with an appropriate blocking agent (e.g., 5% BSA or non-fat milk in TBST) for 1 hour.

- Critical: When using high-sensitivity ECL substrates, it is essential to titrate and often dramatically decrease the concentration of both primary and secondary antibodies to avoid high background and signal saturation. Follow the substrate manufacturer's recommendations.

- Signal Detection:

- Incubate the membrane with the high-sensitivity ECL substrate.

- Image using a digital imager. The stable signal (often >5 hours) allows for multiple exposures to ensure optimal capture without over-saturation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key reagents and materials for studying low-abundance protein targets.

| Item | Function/Purpose | Example Products/Components |

|---|---|---|

| HAP Depletion Kits | Removes high-abundance proteins (e.g., Albumin, IgG) to reduce dynamic range. | MARS columns (Agilent), Seppro kits (Millipore), ProteoPrep (Sigma), Minute kit. |

| Signal Amplification Substrates | Enhances detection signal in immunoassays like western blot. | SignalBright ECL (Proteintech), Tyramide (TSA) kits. |

| DNA-Conjugated Antibodies | Enables DNA-based signal amplification methods. | Custom conjugates for ACE, Immuno-SABER. |

| High-Sensitivity ECL Substrates | Provides ultra-sensitive chemiluminescent detection for western blots. | SignalBright Pro, Plus, Max (Proteintech). |

| Photocrosslinkable Oligos (CNVK) | Stabilizes DNA amplification complexes for mass spectrometry. | CNVK-modified detector oligonucleotides. |

| Ion Exchange Resins | Depletes HAPs based on protein charge. | Used in Norgen's ProteoSpin kit. |

| Validated Primary Antibodies | Ensures specificity and reduces false positives; crucial for low-abundance targets. | Knockout/Knockdown validated antibodies (e.g., from Proteintech). |

| 2-Hydroxy4,7-dimethoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene | 2-Hydroxy4,7-dimethoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene, MF:C16H16O3, MW:256.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| cis-9-Hexadecen-1-yl formate | cis-9-Hexadecen-1-yl formate, MF:C17H32O2, MW:268.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The challenge of detecting low-abundance proteins amidst a sea of high-abundance interferents is a central problem in modern proteomics and biomarker research. Success requires a strategic combination of sample pre-fractionation (e.g., depletion) to reduce complexity and high-sensitivity detection methodologies (e.g., ACE, optimized immunofluorescence) to amplify the signal of interest. The protocols and data provided herein offer a framework for researchers to systematically address this problem. As the field advances, the integration of these methods with robust normalization and calibration techniques [24] [25] will be paramount for achieving the reproducibility and quantitative rigor required for translational research and drug development.

Advanced Strategies for Success: Sample Preparation, Enrichment, and High-Sensitivity Detection

The reliable detection of low-abundance protein targets via immunostaining is a cornerstone of modern biomedical research and drug development. This achievement hinges on a meticulously optimized sample preparation workflow designed to maximize epitope preservation and accessibility. This application note provides a detailed, protocol-driven guide to mastering the critical stages of fixation, permeabilization, and antigen retrieval. Framed within the context of low-abundance target research, we summarize key quantitative data in structured tables, provide step-by-step methodologies, and illustrate optimized signaling pathways and workflows. The following sections are designed to empower researchers to overcome the significant challenges associated with epitope masking and degradation, thereby ensuring high-specificity, high-sensitivity, and reproducible immunostaining results.

Immunostaining allows for the localization of proteins at a quantitative level within cells and tissues [3]. However, the entire immunostaining process is fraught with potential pitfalls that can lead to the misinterpretation of results, including protein loss, relocation, conformational changes, and the masking of epitopes [3]. These challenges are exponentially greater when the target protein is of low abundance. Factors such as over-fixation, improper permeabilization, and inadequate antigen retrieval can obliterate a weak signal or elevate background noise to unacceptable levels. Consequently, a nuanced understanding and precise execution of sample preparation are non-negotiable for researchers aiming to visualize and study rare biomarkers, post-translational modifications, or low-expression gene products effectively.

Critical Stages for Epitope Preservation

Fixation: Balancing Preservation and Accessibility

The primary goal of fixation is to stabilize cells and tissues while preserving morphological detail and preventing degradation [26]. However, the most common fixative, formalin, works by creating protein cross-links, which can obscure antigenic sites and make epitopes inaccessible to antibodies [27] [26]. Therefore, fixation must be a carefully calibrated process.

Protocol: Optimized Formalin Fixation

- Fixative Selection: Use 10% neutral buffered formalin for most applications.

- Fixative Volume: Ensure the volume of fixative is 15-20 times greater than the tissue volume to ensure effective penetration [26].

- Fixation Time: Optimize fixation time based on tissue size. Under-fixation leads to poor morphology and protein loss, while over-fixation excessively masks epitopes. As a general guide, fix small tissue specimens (e.g., mouse organs) for 24-48 hours at room temperature [26]. For cell cultures, 15-30 minutes is often sufficient.

- Post-Fixation Handling: After fixation, tissues should be processed for paraffin embedding or transferred to a 70% ethanol solution for storage to prevent over-fixation and brittleness.

Permeabilization: Enabling Antibody Access

Permeabilization is the process of creating holes in the cellular membranes to allow antibodies to access intracellular targets. This step can be performed as an independent stage or incorporated into the blocking or washing buffers [3]. The choice of agent and concentration is critical, as overly harsh permeabilization can damage cellular structures.

Protocol: Permeabilization for Cultured Cells

- Reagent Preparation: Prepare a permeabilization solution of 0.1-0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS.

- Application: After fixation and washing, incubate cells with the permeabilization solution for 10-15 minutes at room temperature.

- Washing: Rinse cells thoroughly with PBS to remove the detergent. This step can be combined with a blocking step using serum or protein blockers (e.g., BSA) to minimize non-specific antibody binding.

Antigen Retrieval: Reversing Epitope Masking

Antigen retrieval is arguably the most critical step for successful immunostaining of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues. It reverses the cross-links formed during fixation, thereby unmasking epitopes [27]. The two primary methods are Heat-Induced Epitope Retrieval (HIER) and Protease-Induced Epitope Retrieval (PIER), with HIER being generally preferred due to its higher success rate and better preservation of morphology [28].

Protocol: Heat-Induced Epitope Retrieval (HIER) The following protocol can be performed using a pressure cooker, microwave, or vegetable steamer [27].

- Dewax and Rehydrate: Deparaffinize FFPE sections in xylene and rehydrate through a graded series of ethanol to water.

- Select Retrieval Buffer: The choice of buffer and its pH are antigen-dependent. Common buffers include:

- Sodium Citrate (10 mM, pH 6.0)

- Tris-EDTA (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 9.0)

- EDTA (1 mM, pH 8.0)

- Heat Treatment:

- Pressure Cooker Method: Bring the retrieval buffer to a boil in a pressure cooker. Immerse slides, secure the lid, and once full pressure is reached, incubate for 3 minutes. Immediately cool by running cold water over the cooker for 10 minutes [27].

- Microwave Method: Immerse slides in pre-heated retrieval buffer in a microwave-safe vessel. Heat at full power to maintain a boil for 20 minutes, ensuring slides do not dry out. Cool at room temperature for 20-30 minutes.

- Wash: Rinse slides with distilled water and proceed to immunostaining.

Optimization and Data Presentation

Optimizing Antigen Retrieval Conditions

Achieving a strong, specific signal for a low-abundance target often requires empirical optimization of the HIER conditions. The key variables are buffer pH, retrieval time, and temperature [28].

Table 1: Experimental Matrix for Optimizing HIER Conditions

| Time | Antigen Retrieval Solution pH | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Acidic (e.g., Citrate, pH 6.0) | Neutral (e.g., PBS) | Basic (e.g., Tris-EDTA, pH 9.0) | |

| 1 minute | Condition A | Condition B | Condition C |

| 5 minutes | Condition D | Condition E | Condition F |

| 15 minutes | Condition G | Condition H | Condition I |

Researchers should test this matrix using a known positive control tissue to identify the combination that yields the highest signal-to-noise ratio for their specific target [28].

Table 2: Common Antigen Retrieval Buffers and Their Applications

| Buffer | Composition | Typical pH | Recommended For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium Citrate | 10 mM Sodium Citrate, 0.05% Tween 20 | 6.0 | A wide range of nuclear and cytoplasmic antigens [27] |

| Tris-EDTA | 10 mM Tris Base, 1 mM EDTA, 0.05% Tween 20 | 9.0 | Many phospho-targets and more challenging antigens [27] |

| EDTA | 1 mM EDTA | 8.0 | An alternative for certain nuclear antigens |

Visualizing the Optimization Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making pathway for optimizing sample preparation, particularly for challenging low-abundance targets.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

A successful immunostaining experiment relies on high-quality, specific reagents. The following table details key solutions required for the protocols described in this note.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Immunostaining

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin | Chemical fixative that stabilizes tissue architecture and proteins by forming cross-links. | Standard for FFPE tissues; requires precise timing to avoid over-fixation [26]. |

| Triton X-100 | Detergent for permeabilizing cell membranes to allow antibody entry into cells. | Use at 0.1-0.5% in PBS; concentration and time require optimization. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail | Prevents proteolytic degradation of target proteins during cell lysis and sample preparation. | Essential addition to lysis buffers for labile or low-abundance targets [14]. |

| HIER Buffers (Citrate, Tris-EDTA) | Breaks methylene cross-links formed during formalin fixation, unmasking epitopes for antibody binding. | pH is critical; selection is antigen-dependent [27] [28]. |

| Blocking Serum (e.g., BSA, NGS) | Reduces non-specific binding of antibodies to the tissue, thereby lowering background signal. | Prepare in TBST; serum should match the species of the secondary antibody. |

| Primary Antibody | Binds with high specificity to the target antigen of interest. | Must be validated for IHC/ICC; use higher concentrations for low-abundance targets [14]. |

| Trilobatin 2''-acetate | Trilobatin 2''-acetate, MF:C23H26O11, MW:478.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 10-Hydroxy-2,6,10-trimethyl-2,6,11-dodeca-4-one | 10-Hydroxy-2,6,10-trimethyl-2,6,11-dodeca-4-one, MF:C15H24O2, MW:236.35 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Concluding Remarks

Mastering sample preparation is not a mere preliminary step but the foundational element upon which reliable immunostaining data is built. This is especially true in the demanding field of low-abundance protein research, where the margin for error is minimal. By systematically optimizing fixation, permeabilization, and—most crucially—antigen retrieval, researchers can dramatically enhance epitope preservation, maximize signal-to-noise ratio, and ensure the reproducibility of their findings. The protocols, optimization strategies, and reagent knowledge contained in this application note provide a concrete pathway to achieving this mastery, ultimately supporting robust and impactful scientific discovery.

The detection of low-abundance proteins represents a significant challenge in biomedical research, particularly in the study of signaling pathways, biomarker discovery, and drug development. Proteins exist in mammalian cells across an extraordinary concentration range of at least seven orders of magnitude, with many functionally important proteins such as transcription factors and cell-surface cytokine receptors expressing at levels below the detection threshold of conventional immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence techniques [29]. This limitation has driven the development of sophisticated signal amplification methodologies that enable researchers to visualize and quantify these elusive targets without fundamentally perturbing the finely balanced molecular interaction networks that underlie cellular function [29].

Signal amplification techniques have evolved to address two primary needs in biomedical research: enhancing sensitivity for targets present in limited copies per cell and enabling multiplexed detection of several targets within the same sample. Among these techniques, Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA) has emerged as a powerful enzyme-mediated method that substantially increases detection sensitivity for both proteins and nucleic acids [30] [31]. Also known as Catalyzed Reporter Deposition (CARD), TSA leverages the catalytic activity of horseradish peroxidase (HRP) to generate high-density labeling of target molecules, achieving up to 100-fold greater sensitivity compared to conventional detection methods [31]. This enhanced sensitivity is particularly valuable for researchers investigating spatial relationships within tissue microenvironments, where the simultaneous detection of multiple low-abundance targets can provide critical insights into cellular interactions and disease mechanisms [32].

Principles of Tyramide Signal Amplification

Fundamental Mechanism

Tyramide Signal Amplification is based on the catalytic activity of horseradish peroxidase (HRP) to generate highly reactive tyramide radicals that covalently bind to tyrosine residues in proteins surrounding the enzyme site [30] [33]. The fundamental process begins when a target molecule of interest is labeled with HRP enzymes through specific antibodies. When the labeled tissue is exposed to a solution containing biotinylated or fluorophore-conjugated tyramine and hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚), the HRP enzyme catalyzes the oxidation of the phenolic part of tyramine [30]. This reaction generates a quinone-like structure containing a radical on the C2 group of tyramine, creating "activated" tyramine that subsequently forms covalent bonds with electron-rich tyrosine residues on nearby proteins [30].

The covalent nature of tyramide deposition is a key feature that distinguishes TSA from conventional detection methods. Unlike standard immunofluorescence techniques that rely on affinity binding, the covalent bonding of tyramide substrates creates a stable signal that remains localized to the site of the HRP enzyme, resulting in excellent spatial resolution [31]. This localization is critical for accurate subcellular localization studies and prevents signal diffusion that could compromise experimental results. Each HRP enzyme can activate multiple tyramide substrate molecules, creating a substantial amplification effect that dramatically enhances detection sensitivity for low-abundance targets that would otherwise remain undetectable [31].

Direct vs. Indirect Detection Approaches

TSA can be implemented through either direct or indirect detection approaches, each offering distinct advantages for specific applications. In the direct TSA method, the tyramide substrate is conjugated directly to a fluorophore, allowing immediate signal detection after the deposition reaction without requiring additional detection steps [30]. This approach provides good spatial resolution and high signal intensity while simplifying the experimental workflow. The direct method is particularly advantageous when minimal background and streamlined procedures are priorities.

In contrast, the indirect TSA approach utilizes hapten-labeled tyramides, most commonly biotin-XX tyramide, which requires a subsequent detection step with a streptavidin conjugate or anti-hapten antibody [31]. Although this method adds complexity to the protocol, it provides additional flexibility as the same hapten-labeled tyramide can be detected with different conjugates, enabling researchers to customize the detection methodology based on their specific needs. The indirect approach also offers potential for further signal amplification through additional enzymatic steps, which can be beneficial for exceptionally challenging targets [31].

Comparative Advantage Over Conventional Methods

TSA methodology offers several significant advantages over conventional detection techniques. When compared to standard avidin-biotinylated enzyme complex (ABC) procedures, TSA has demonstrated up to 100-fold improvement in detection sensitivity [31]. This enhanced performance translates into practical benefits for researchers, including the ability to use dramatically lower concentrations of primary antibodies - in some cases up to 50-fold higher dilutions - while still obtaining robust signals [30]. This antibody conservation is particularly valuable when working with rare or expensive antibodies.

The amplification power of TSA also enables detection of targets that are simply undetectable with conventional methods. For example, researchers have successfully utilized TSA to detect low-abundance epidermal growth factor (EGF) and estrogen receptors by flow cytometry with far greater sensitivity than achievable using directly labeled probes or standard fluorophore-labeled antibodies [31]. Similarly, TSA has proven effective for fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) applications, enabling detection of low-abundance mRNAs and facilitating definitive results in a single day, which is notably faster than other FISH techniques [30].

TSA Protocols and Methodologies

Standard TSA Workflow for Immunohistochemistry

The implementation of Tyramide Signal Amplification follows a systematic workflow that shares similarities with conventional immunohistochemistry but incorporates critical amplification steps. The following protocol outlines the standard procedure for TSA-based detection of low-abundance proteins in cell cultures or tissue sections:

Sample Preparation: Fix cells or tissue sections using appropriate fixatives (typically formaldehyde-based) followed by permeabilization to allow antibody access to intracellular targets. The fixation step must be optimized to preserve antigenicity while maintaining cellular structure [33].

Blocking: Incubate samples with a blocking buffer to minimize non-specific binding of antibodies. TSA-specific blocking reagents are often included in commercial kits to further reduce background signal [31].

Primary Antibody Incubation: Apply target-specific primary antibody diluted in an appropriate buffer. Due to the signal amplification, primary antibodies can typically be used at significantly higher dilutions (e.g., 10- to 100-fold higher) compared to conventional IHC [30]. Incubation conditions (time, temperature) should be optimized for each antibody.

HRP-Conjugated Secondary Antibody Incubation: Detect the primary antibody using a species-specific secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. Alternatively, HRP-conjugated streptavidin can be used if a biotinylated primary antibody was employed [33] [31].

Tyramide Substrate Incubation: Prepare the tyramide working solution according to manufacturer instructions, typically by diluting the tyramide reagent in amplification buffer and adding Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ immediately before use. Incubate the samples with this working solution for precisely optimized duration (usually 2-10 minutes) to achieve optimal signal-to-noise ratio [33] [31].

Signal Detection: For fluorescent TSA, directly visualize the signal using appropriate microscopy filters. For chromogenic or biotinylated tyramide, perform additional detection steps as needed [30].

Counterstaining and Mounting: Apply nuclear counterstains (e.g., DAPI) if desired, and mount samples using antifade mounting media for fluorescence preservation [31].

Throughout this workflow, careful optimization of each step is essential, particularly for the tyramide incubation time, which significantly impacts signal intensity and background levels.

Multiplex Immunohistochemistry Using TSA

A powerful application of TSA technology is in multiplex immunohistochemistry (mIHC), which enables simultaneous detection of multiple protein targets on a single tissue section. The sequential nature of TSA staining, combined with efficient antibody stripping between cycles, makes it ideal for visualizing complex cellular populations and spatial relationships within tissues [32]. The general workflow for TSA-based mIHC includes:

First Target Staining: Complete the full TSA protocol for the first protein target using a specific fluorophore-labeled tyramide (e.g., Opal 520).

Antibody Stripping: Apply an optimized antibody removal method to eliminate primary and secondary antibodies while preserving the covalently deposited tyramide signal. Recent studies have demonstrated that hybridization oven-based antibody removal at 98°C (HO-AR-98) effectively strips antibodies while better preserving tissue integrity in delicate samples compared to microwave-assisted methods [32].

Validation of Stripping Efficiency: Confirm complete antibody removal by attempting to detect signal using the fluorophore from the previous cycle. Absence of signal indicates successful stripping.

Subsequent Target Staining: Repeat the TSA staining process for the next target using a different fluorophore-labeled tyramide (e.g., Opal 570, Opal 620, Opal 690).

Iterative Staining: Continue the cycle of staining and stripping for additional targets, typically up to 6-8 markers on a single section [32].

Final Visualization: Acquire multispectral images using appropriate fluorescence filters or spectral imaging systems.

This multiplexing approach enables researchers to characterize complex tissue microenvironments, such as the tumor immune microenvironment, with unprecedented resolution while conserving precious samples.

Technical Considerations and Optimization

Successful implementation of TSA requires careful attention to several technical aspects. The activity of the HRP enzyme is critical for optimal performance, and sodium azide should be strictly avoided in all buffers as it inhibits HRP activity [14]. The concentration of hydrogen peroxide in the tyramide working solution must be carefully controlled, as excessive Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ can lead to increased background signal or enzyme inactivation [31].

For multiplex applications, the antibody stripping step requires particular optimization. Different tissue types may respond differently to various stripping conditions. For example, brain tissues prone to delamination benefit from hybridization oven-based stripping at 98°C (HO-AR-98), which better preserves tissue integrity compared to microwave-assisted removal [32]. The sequence of target detection should also be planned strategically, with less abundant targets typically stained first and brighter fluorophores reserved for targets requiring higher sensitivity.

Appropriate controls are essential for validating TSA results. These should include samples without primary antibody (to assess background from secondary reagents), samples without tyramide substrate (to confirm signal amplification is TSA-dependent), and if possible, comparison with conventional detection methods to demonstrate enhanced sensitivity.

Complementary Techniques for Low-Abundance Protein Detection

Enhanced Western Blotting for Low-Abundance Proteins

While TSA excels in immunohistochemistry applications, detecting low-abundance proteins via Western blotting requires alternative optimization strategies. Enhanced Western blot protocols for low-abundance targets focus on several key areas: sample preparation, transfer efficiency, and sensitive detection methods [14].

Sample preparation is critical for successful detection of low-abundance proteins. For proteins localized to specific cellular compartments, such as transcription factors in the nucleus or membrane proteins, use of appropriate lysis buffers is essential. RIPA buffer containing SDS is recommended for complete lysis of intracellular compartments, while fractionation kits can enrich specific subcellular fractions [14] [34]. To prevent protein degradation, broad-spectrum protease inhibitor cocktails should be included during cell lysis, and for phosphorylated proteins, phosphatase inhibitors are essential [14]. For membrane proteins, high-temperature heating should be avoided as it can cause aggregation; instead, incubation at room temperature or 70°C is recommended [14].

Electrophoresis and transfer conditions significantly impact detection sensitivity. Increasing sample load to 50-100 μg per lane on SDS-polyacrylamide gels with 1.5 mm combs increases the amount of target protein [14]. PVDF membranes are preferred over nitrocellulose for their higher protein-binding capacity and reduced non-specific antibody binding, which improves the signal-to-noise ratio for low-abundance targets [14] [34]. Transfer efficiency should be verified using Ponceau red staining, particularly for high molecular weight proteins that may require extended transfer times [14].

Detection optimization includes using higher concentrations of primary antibodies with overnight incubation at 4°C and employing enhanced chemiluminescent substrates specifically designed for high sensitivity. These substrates, such as the SignalBright series, can detect femtogram levels of protein and provide a bright, stable signal for over 5 hours, facilitating optimal image capture [34].

Advanced Methodologies for Single-Molecule Sensitivity

For applications requiring ultimate sensitivity, several advanced methodologies have been developed that enable single-molecule detection of proteins and nucleic acids. Digital ELISA techniques, such as Simoa (Single Molecule Array), represent the current state-of-the-art in protein detection sensitivity, achieving detection limits below 1 fM [35]. These methods work by isolating individual protein molecules in femtoliter-sized wells along with enzyme-linked immunocomplexes, allowing detection of single enzyme-labeled molecules through fluorogenic or chromogenic substrates.

For nucleic acid detection, digital PCR provides absolute quantification of target nucleic acids without the need for standard curves, achieving a 0.1% variant allele frequency compared to 1% with conventional qPCR [35]. This technique involves partitioning samples into thousands of individual reactions, with each partition containing zero or one target molecule, followed by amplification and detection of positive partitions.

Bona fide single-molecule techniques such as SiMPull (Single Molecule Pull-Down) and SIMPlex (Single Molecule Interaction Pull-Down) enable direct visualization and quantification of individual protein molecules and their complexes without amplification steps, achieving sensitivity down to 1 pM [35]. These methods combine specific pull-down of target proteins with single-molecule fluorescence microscopy, providing unprecedented insights into protein complexes and interactions.

Comparison of Signal Amplification Techniques

The selection of an appropriate signal amplification method depends on multiple factors, including the abundance of the target, required sensitivity, available equipment, and experimental goals. The table below provides a comparative overview of major signal amplification techniques:

Table 1: Comparison of Signal Amplification Techniques for Low-Abundance Protein Detection

| Technique | Principle | Sensitivity Enhancement | Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA) | HRP-catalyzed deposition of tyramide conjugates | Up to 100-fold vs. conventional IHC [31] | IHC, ICC, FISH, flow cytometry | High sensitivity, compatible with standard equipment, enables multiplexing | Optimization required, potential for high background if over-amplified |

| Enhanced Chemiluminescence | Optimized substrates for HRP-luminol reaction | Femtogram protein detection [34] | Western blotting | Extreme sensitivity, wide dynamic range | Limited to Western blot applications |

| Enzyme-Labeled Fluorescence (ELF) | Alkaline phosphatase substrates forming fluorescent precipitates | ~10-fold vs. standard fluorescence [29] | IHC, ICC, cell-based assays | Very bright signal, photostability | Limited multiplexing capability |

| Macrofluorophores | Multiple fluorophores on common scaffold | Varies with fluorophore number | Flow cytometry, imaging | Bright signals without enzymatic steps | Potential nonspecific binding |

| Digital ELISA (Simoa) | Single molecule detection in femtoliter wells | <1 fM sensitivity [35] | Protein quantification in biofluids | Extreme sensitivity, digital quantification | Specialized equipment required |

| Single Molecule Pull-Down (SiMPull) | Combination of pull-down with single molecule microscopy | 1 pM sensitivity [35] | Protein complex analysis, interactions | Single molecule resolution, quantitative | Technically challenging, specialized setup |

Essential Reagents and Tools for Signal Amplification

Successful implementation of signal amplification techniques requires specific reagents and tools optimized for these sensitive applications. The following table outlines key components for establishing TSA and related methodologies:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Signal Amplification Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tyramide Reagents | Alexa Fluor tyramides (488, 546, 594, 647) [33] [31]; Cy3, Cy5 tyramides [33]; Biotin-XX tyramide [31] | Signal amplification substrate | Fluorophore selection should match available filter sets; biotinylated tyramide enables additional flexibility |

| Enzyme Conjugates | HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies [31]; HRP-conjugated streptavidin [33]; Zenon HRP Antibody Labeling Kits [31] | Target recognition with enzymatic activity | Anti-mouse, anti-rabbit most common; Zenon kits enable HRP labeling of primary antibodies |

| Amplification Buffers | TSA reaction buffer [31]; Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ reaction additive [31] | Optimal enzymatic activity | Fresh Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ critical for consistent results; commercial buffers ensure optimal pH and composition |

| Blocking Reagents | TSA blocking reagent [31]; Protein block sera; BSA-based blockers | Reduce nonspecific background | TSA-specific blockers minimize nonspecific tyramide deposition |

| Antibody Stripping Solutions | High-temperature buffer (HO-AR-98) [32]; Commercial stripping reagents [32] | Antibody removal for multiplexing | Temperature and pH critical for efficiency; HO-AR-98 preserves delicate tissues |

| Sensitive Detection Substrates | SignalBright ECL substrates [34]; Opal fluorophores [32] | Signal generation | ECL substrates vary in sensitivity and signal duration; opal fluorophores optimized for multiplex IHC |

Signal amplification techniques, particularly Tyramide Signal Amplification, have revolutionized the detection of low-abundance proteins in biomedical research. The exceptional sensitivity of TSA—up to 100-fold greater than conventional methods—enables researchers to visualize and quantify biologically important targets that were previously undetectable, from transcription factors and cell-surface receptors to rare biomarkers in pathological samples [31]. When combined with multiplexing approaches, TSA provides unprecedented insights into complex cellular environments and protein interactions within their native context.

The successful implementation of these techniques requires careful optimization of multiple parameters, including sample preparation, antibody concentrations, tyramide incubation times, and for multiplex applications, efficient antibody stripping protocols [32]. As research continues to push the boundaries of detection sensitivity, particularly in fields such as liquid biopsy and single-cell analysis, the integration of TSA with emerging technologies like digital detection methods and advanced imaging platforms will further expand our capability to explore the molecular intricacies of biological systems and disease processes.

Within the framework of immunostaining research for low-abundance protein targets, effective protein enrichment is a critical prerequisite for successful detection and analysis. The immense complexity of biological samples and the vast dynamic range of protein concentrations often obscure low-abundance targets, making their direct visualization challenging [36] [37]. This application note details three powerful enrichment methodologies—ProteoMiner, magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs), and immunoaffinity partitioning—providing detailed protocols and application data to guide researchers in selecting and implementing the optimal strategy for their specific research needs in drug development and diagnostic science.

The following table summarizes the core characteristics and performance metrics of the three featured enrichment technologies, aiding in the selection of an appropriate method.

Table 1: Comparison of Protein Enrichment Technologies

| Technology | Principle of Action | Best For | Typical Sample Input | Key Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ProteoMiner | Equalizes protein abundance via a vast library of hexapeptide ligands [38]. | Comprehensive proteome discovery; identifying "missing proteins" [38]. | 100 µL - 1 mL of serum/plasma or tissue extract [38]. | Identified 20 previously "missing" proteins from human tissues; effective enrichment of low-abundance and membrane/secreted proteins [38]. |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles (MNPs) | Surface-functionalized particles for affinity binding, separated magnetically [39] [40]. | Rapid purification from complex matrices (e.g., silkworm fat body, E. coli lysate) [39]. | 0.5 - 1 mL of cell lysate or clarified plasma [39] [36]. | ~77.7% reduction in host proteins; ~50.8% recovery of target protein; binding capacity of 83.3 µg/mg MNP [39]. |

| Immunoaffinity Partitioning | High-affinity antibodies immobilized on beads or tips capture specific antigens [36] [37]. | Ultra-specific target enrichment for validation; quantifying specific isoforms [36] [37]. | 0.5 mL plasma [36]. | Intra- and inter-assay CV < 15%; >1400 samples analyzed in <3 weeks; 10-fold lower LLOQ vs. bead-based methods [36] [37]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Protein Enrichment Using Magnetic Nanoparticles (e.g., Ni-NTA for His-Tagged Proteins)

This protocol is adapted for purifying His-tagged recombinant proteins from a complex silkworm fat body lysate using Ni-modified MNPs [39].

Materials: