Antibody Validation for Immunohistochemistry: A Comprehensive Guide to Protocols, Pitfalls, and Best Practices

This article provides a comprehensive guide to antibody validation protocols for immunohistochemistry (IHC), tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Antibody Validation for Immunohistochemistry: A Comprehensive Guide to Protocols, Pitfalls, and Best Practices

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to antibody validation protocols for immunohistochemistry (IHC), tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of validation, including the critical distinction from verification and optimization. The guide details established methodological frameworks like the 'Five Pillars' and stepwise approaches for application-specific testing. It further addresses common troubleshooting scenarios and protocol optimization techniques to enhance specificity and sensitivity. Finally, it outlines the latest regulatory and comparative validation standards, including updates from the College of American Pathologists (CAP) and strategies for predictive marker assays. By synthesizing current guidelines and practical strategies, this resource aims to empower professionals to implement robust validation practices, ensuring the reliability and reproducibility of IHC data in both research and clinical contexts.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Principles and Definitions of IHC Antibody Validation

In the field of immunohistochemistry (IHC) research, the reliability of experimental results and the validity of diagnostic biomarkers are fundamentally dependent on rigorous antibody validation. As the research community continues to address challenges related to reproducibility, establishing standardized validation protocols has become increasingly critical. Antibody validation is a comprehensive process that demonstrates an antibody is specific for its target, sensitive enough to detect the target at biologically relevant levels, and capable of producing reproducible results across repeated experiments [1]. For researchers and drug development professionals, implementing systematic validation protocols ensures that IHC-based data accurately reflects biological reality, ultimately supporting robust scientific conclusions and informed clinical decisions.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of antibody validation approaches, focusing on the core pillars of specificity, sensitivity, and reproducibility within IHC applications. We examine experimental methodologies, present quantitative performance data, and outline structured frameworks adopted by leading organizations to establish standardized validation practices in histopathology research.

Core Principles of Antibody Validation

The Three Pillars of Validation

Antibody validation for IHC applications rests on three fundamental principles that collectively ensure reliable performance:

- Specificity: The ability of an antibody to bind exclusively to its intended target antigen, demonstrated through various experimental techniques that confirm absence of cross-reactivity with non-target proteins [1].

- Sensitivity: The lowest level at which an antibody can reliably detect its target antigen, reflecting the detection threshold and dynamic range appropriate for the biological context [1].

- Reproducibility: The consistency of antibody performance across different lots, experimental conditions, time points, and operators, ensuring that results are reliable and repeatable [2] [1].

Regulatory and Standards Framework

Recent updates to validation guidelines reflect the evolving landscape of IHC applications. The College of American Pathologists (CAP) released updated principles in 2024 that harmonize validation requirements for predictive markers, establish specific guidelines for cytology specimens, and standardize concordance rates at 90% for all IHC assays [3]. These evidence-based recommendations provide a framework for laboratories to enhance the quality and safety of clinically important assays, though adoption remains voluntary unless incorporated into specific accreditation requirements.

Comparative Analysis of Antibody Performance

The performance characteristics of antibodies vary significantly based on their production methodology and validation rigor. The table below summarizes key differences between major antibody classes:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Antibody Types in IHC Applications

| Parameter | Recombinant Monoclonal Antibodies | Traditional Monoclonal Antibodies | Polyclonal Antibodies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specificity | High (defined amino acid sequence) [2] | High (single epitope) [4] | Variable (multiple epitopes) [4] |

| Sensitivity | Consistent, optimized during development | Variable between clones | Generally high [4] |

| Reproducibility | Excellent (no lot-to-lot variation) [2] | Good (with proper hybridoma banking) | Poor (significant lot-to-lot variation) |

| Success Rate in FFPE | High (engineered for formalin-resistant epitopes) | ~50% success rate [4] | 60-75% success rate [4] |

| Cross-reactivity | Minimal (BLAST analysis of peptide sequence) [4] | Low | Higher potential [4] |

| Long-term Supply | Guaranteed (sequence preserved) | Conditionally guaranteed | Not guaranteed |

The move toward recombinant antibody technology represents a significant advancement in addressing reproducibility challenges. Recombinant antibodies are produced through gene cloning, which ensures precise amino acid sequences and eliminates the biological variability inherent in traditional hybridoma-based methods [2]. One leading provider reports that nearly 99% of their new antibodies are now produced using recombinant technology, reflecting the industry's commitment to overcoming the reproducibility crisis [2].

Experimental Protocols for Antibody Validation

Tiered Validation Framework

A consensus approach developed by academic and pharmaceutical histopathology researchers proposes a tiered system for antibody validation [1]. The degree of validation required is proportionate to an antibody's placement within this framework:

- Tier 1: Well-characterized antibodies with substantial high-quality literature evidence

- Tier 2: Established antibodies used in alternative species or unvalidated tissue types

- Tier 3: Unknown antibodies with inconsistent or no literature evidence

Stepwise Validation Methodology

A comprehensive validation protocol involves multiple experimental approaches to address specificity, sensitivity, and reproducibility:

1. Target Characterization A thorough literature review using databases such as OMIM, Uniprot, and Genecards establishes expected expression patterns, biological relevance, and subcellular localization [1]. This foundational knowledge informs validation design and helps identify non-specific interactions.

2. Control Material Identification Positive and negative control materials are critical for validation [1]. These may include:

- Cultured cell lines with known expression profiles

- FFPE cell blocks processed to mimic tissue samples

- Tissue microarrays (TMAs) containing multiple tissue types

- CRISPR-Cas9 engineered cells for target confirmation [5]

3. Specificity Validation

- Western Blot Analysis: Demonstrates specific bands at appropriate molecular weights with minimal cross-reactivity [6] [1].

- Cell Line Validation: Using transfected cell lines expressing different target levels or siRNA knockdown to confirm target specificity [1] [4].

- Blocking Peptides: Competition experiments with target peptides verify specificity and rule out Fc-mediated binding [6].

- BLAST Analysis: For peptide-targeting antibodies, sequence similarity searches confirm peptide uniqueness [4].

4. IHC Optimization and Validation

- Antigen Retrieval Optimization: Testing multiple retrieval conditions to maximize signal-to-noise ratio [1].

- Titration Studies: Determining optimal antibody concentration using a range of dilutions [4].

- Tissue Staining Pattern Assessment: Comparing results with expected architectural and subcellular localization [3] [1].

- Multi-tissue Validation: Testing antibody performance across a broad spectrum of tissue types [6] [4].

Table 2: Key Validation Experiments and Their Applications

| Validation Method | Primary Application | Data Output | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Western Blot | Specificity confirmation | Molecular weight confirmation | Poor predictor of IHC performance [4] |

| Cell Pellet Arrays | Specificity, optimal dilution | Staining pattern in defined systems | Must mimic tissue processing [1] |

| Tissue Microarrays | Broad tissue performance | Staining across multiple tissues | Efficient use of tissue resources [1] |

| Blocking Peptides | Specificity confirmation | Loss of staining with competitor | Rules out non-specific binding [6] |

| Xenograft Models | Performance in disease models | Staining in relevant pathology | Verifies target specificity [6] |

Analytical Techniques for Characterization

Advanced analytical techniques provide quantitative data on antibody performance:

High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS) HRMS offers unparalleled precision in identifying post-translational modifications and determining molecular weights, ensuring batch-to-batch consistency of therapeutic antibodies [5].

Analytical Affinity Chromatography Optimized using design of experiments (DoE) approaches, this method enables accurate quantification of tagged products with high specificity, linearity, accuracy, and precision [7]. Validated according to International Conference on Harmonisation Q2(R2) guidelines, it achieves minimal analyte carryover (98.8 ± 0.1% product elution) and superior performance compared to traditional ELISA methods [7].

Pull-Down Assays As a form of affinity purification, pull-down assays confirm protein-protein interactions using tagged "bait" proteins captured on immobilized affinity ligands [8]. This technique is particularly valuable for investigating the activation status of specific proteins, such as GTPases cycling between GTP-bound (active) and GDP-bound (inactive) states [8].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table outlines essential reagents and their functions in antibody validation workflows:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Antibody Validation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Control Materials | FFPE cell pellets, tissue arrays, xenografts [6] [1] | Provide known positive/negative samples for specificity testing |

| Detection Systems | HRP-DAB, alkaline phosphatase-Vector Red, fluorescent tags [9] [4] | Enable visualization of antibody-antigen binding |

| Affinity Matrices | Glutathione agarose, nickel/cobalt chelate, streptavidin beads [8] | Immobilize bait proteins for interaction studies |

| Validation Antibodies | Cytokeratin, vimentin, CD markers, phospho-tyrosine [1] [4] | Assess tissue quality and antigen preservation |

| Tagging Systems | GST, polyHis, biotin tags [8] | Facilitate purification and detection of recombinant proteins |

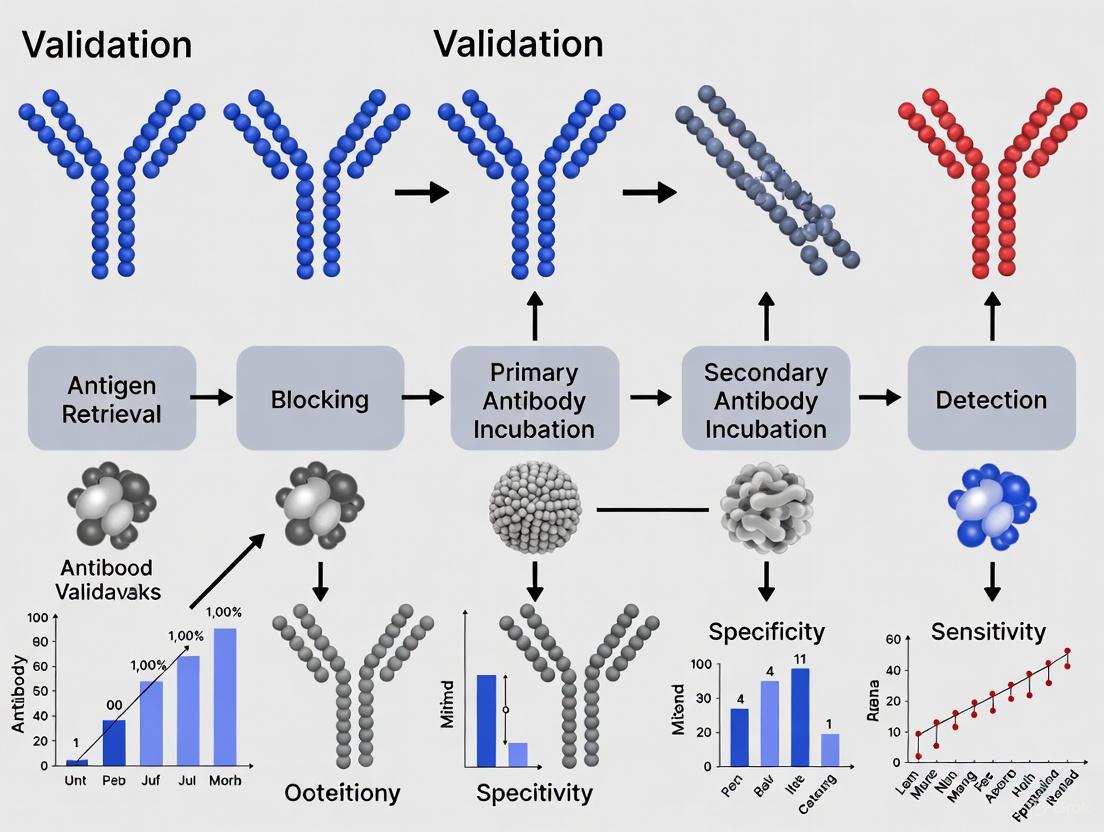

Validation Workflow and Decision Pathways

The antibody validation process follows a logical sequence from initial target characterization through final implementation. The diagram below illustrates this workflow, highlighting key decision points and methodological selections:

Validation Workflow Diagram: This flowchart illustrates the systematic approach to antibody validation, from initial target characterization through final implementation, including key methodological considerations and assessment criteria.

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

The field of antibody validation continues to evolve with several emerging technologies shaping future practices:

Recombinant Antibody Technologies Recombinant antibodies represent the present and future of reliable antibody reagents, with their precise gene cloning enabling exceptional reproducibility and eliminating lot-to-lot variability [2]. Leading suppliers have committed to this technology, with nearly 99% of new antibodies now produced using recombinant methods [2].

Automation and Artificial Intelligence The integration of automation and AI is transforming characterization processes by enhancing efficiency, accuracy, and predictive capabilities [5]. Machine learning algorithms can predict chemical properties, binding affinities, and toxicity profiles from large datasets, while automated platforms improve reproducibility in high-throughput screening and sample preparation [5].

Advanced Characterization Platforms Next-generation platforms offer improved sensitivity and resolution for antibody characterization:

- Hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS): Provides insights into antibody stability and conformational dynamics [5].

- Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM): Enables high-resolution structural imaging of antibody-antigen interactions [5].

- High-resolution mass spectrometry: Delivers unparalleled precision in identifying post-translational modifications [5].

Comprehensive antibody validation encompassing specificity, sensitivity, and reproducibility is fundamental to advancing IHC research and biomarker development. The comparative data and methodologies presented in this guide demonstrate that recombinant antibody technologies consistently outperform traditional alternatives in critical validation parameters, particularly in addressing the reproducibility challenges that have plagued historical research efforts.

As the field evolves, adherence to standardized validation frameworks—such as the tiered approach and CAP guidelines—provides a pathway toward more reliable research outcomes. The implementation of robust validation protocols, supported by emerging technologies in automation, AI, and advanced analytics, will continue to enhance the quality of IHC data, ultimately accelerating drug development and improving diagnostic accuracy for research and clinical applications.

In the rigorous field of immunohistochemistry (IHC) research, the reliability of experimental data is paramount. Inconsistent antibody performance is a major contributor to the scientific reproducibility crisis, potentially wasting billions of dollars annually and leading to erroneous conclusions [10]. A foundational step to mitigating this risk lies in understanding and implementing three distinct but often confused processes: validation, verification, and optimization. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, applying these concepts correctly is not merely a matter of semantics but a critical component of robust experimental design and trustworthy antibody validation protocols. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of these processes, framed within the context of IHC research, to empower professionals in building a solid foundation for their scientific discoveries.

Definitive Meanings: A Comparative Framework

The terms validation, verification, and optimization describe different levels of assurance regarding an antibody's performance. Their specific definitions, triggers, and regulatory standing are distinct [11] [12].

The table below summarizes the core objectives and drivers for each process.

| Process | Core Objective | When It Is Required | Regulatory & Standard Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Validation | To establish performance specifications for a new test through rigorous evidence [11]. | Introducing a new test, antibody, or clone; a new platform; a different fixative; or decalcification process [12]. | CLIA § 493.1253; CAP: ANP.22750, ANP.22978 [12]. |

| Verification | To confirm that a previously validated test performs as expected after a minor change [11]. | Changing antigen retrieval methods; switching manufacturers for an established clone; lot-to-lot checks [12]. | CLIA § 493.1253; CAP: ANP.22750, ANP.22978 [12]. |

| Optimization | A trial-and-error phase to fine-tuning protocols for the best staining results [12]. | Introducing a new antibody/clone; adjusting pre-analytical factors (fixation times); pathologist-requested stain changes [12]. | Considered a pre-validation/verification activity; governed by internal lab SOPs. |

Optimization is a trial-and-error phase where protocols are fine-tuned to achieve the best possible staining results in terms of specificity and signal strength. This process is a prerequisite before any formal validation or verification can begin and involves tweaking parameters like antibody dilution, incubation times, and antigen retrieval methods [12].

Validation is the comprehensive process of establishing performance specifications for a new test through the provision of objective evidence that it meets the requirements for its intended use [11]. In IHC, this is required for laboratory-developed tests (LDTs) and any modification to an FDA-cleared/approved assay. The updated CAP guidelines emphasize rigorous study design, often requiring a minimum of 20 positive and 20 negative cases for predictive markers and setting a 90% concordance threshold for all IHC assays [3] [11].

Verification is the process of confirming that a previously validated test or assay performs as expected in your laboratory after a minor change. It is generally less extensive than validation. For example, when using an unmodified FDA-cleared/approved assay, a laboratory performs verification to ensure the test performs as stated by the manufacturer. Similarly, checking a new lot of an established antibody or verifying a test on a new control block falls under verification [11] [12].

Diagram 1: Decision workflow for optimization, validation, and verification.

Experimental Protocols and Data Standards

The experimental design and required evidence for validation, verification, and optimization differ significantly in scope and stringency. Adherence to established guidelines is critical for assay acceptance.

Validation Protocols and Concordance Standards

For IHC assay validation, the College of American Pathologists (CAP) provides definitive guidelines. The process requires testing on cases with predetermined expected results. The nature and number of these cases depend on the assay type [11]:

- Predictive markers (e.g., HER2, PD-L1): A minimum of 20 positive and 20 negative cases is recommended.

- Non-predictive markers: A minimum of 10 positive and 10 negative cases is recommended.

The updated 2024 CAP guideline harmonizes the concordance requirement for all IHC assays to a minimum of 90% when compared to a predetermined standard [3]. The selection of an appropriate comparator is vital for validation study design. CAP guidelines list several options, ordered here from most to least stringent [3]:

- Comparison to IHC results from cell lines with known amounts of protein ("calibrators").

- Comparison with a non-immunohistochemical method (e.g., flow cytometry, FISH).

- Comparison with results from another laboratory using a validated assay.

- Comparison with prior testing of the same tissues in the same laboratory.

For assays on cytology specimens or tissues fixed in alternative fixatives, a separate validation with a minimum of 10 positive and 10 negative cases is required due to variable sensitivity compared to standard FFPE tissues [3].

Verification and Optimization Procedures

Verification of an FDA-cleared/approved assay should follow the manufacturer's instructions. If these are absent, the process often adopts the principles of validation, with the laboratory director determining the appropriate number of samples [11]. A typical verification for a new antibody lot might involve running a small set of known positive and negative controls alongside the old lot to ensure staining consistency.

Optimization is an iterative process without a fixed sample number. It begins with selecting an appropriate tissue known to express the target antigen and a negative control. The manufacturer's protocol is followed initially, and conditions are adjusted as needed. This includes varying antibody dilution, incubation time, and antigen retrieval parameters (e.g., pH of retrieval buffer, method of heat induction) until a specific staining pattern with minimal background is achieved [11] [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful IHC experiments rely on a suite of critical reagents and materials. The table below details key components and their functions in the experimental workflow.

| Tool/Reagent | Function & Role in IHC Workflow |

|---|---|

| Primary Antibodies | The core reagent that specifically binds to the target protein (antigen). Rigorous validation for IHC application is critical [13]. |

| Detection Kit | Contains secondary antibodies and detection enzymes (e.g., HRP) or fluorophores to visualize the primary antibody binding [13]. |

| FFPE Tissue Sections | Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded tissues are the most common sample type, preserving tissue architecture for analysis [13]. |

| Antigen Retrieval Buffers | Critical solutions (e.g., Citrate pH 6.0, EDTA pH 8.0) used to unmask epitopes cross-linked during fixation, making them accessible to antibodies [13]. |

| Blocking Serum | A protein solution used to cover non-specific binding sites on the tissue, reducing background noise and improving signal-to-noise ratio [13]. |

| Counterstains | Dyes like Hematoxylin that stain cell nuclei, providing histological context for the protein localization revealed by IHC [13]. |

| Mounting Medium | Aqueous or permanent media used to preserve the stain and optimize the refractive index for microscopy after applying a coverslip [13]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 KO Cell Lines | Genetically engineered cells used as a gold-standard negative control to confirm antibody specificity by showing signal loss when the target gene is knocked out [10] [14]. |

Advanced Considerations and Future Directions

The field of antibody validation is evolving, with new guidelines and techniques enhancing reproducibility. A significant update in the 2024 CAP guideline is the requirement to separately validate each assay-scoring system combination for predictive markers like HER2 and PD-L1, which employ different scoring systems based on tumor site or type [3].

Furthermore, the distinction between immunohistochemistry (IHC) and immunocytochemistry (ICC) is crucial. IHC is performed on tissue sections, preserving extracellular architecture, while ICC is used on individual cells without a matrix. Experts increasingly recommend precise nomenclature: using "immunohistofluorescence" or "immunocytofluorescence" to clarify both the sample type and detection method, which is critical for validation and reproducibility [15].

Leading antibody manufacturers are now adopting multi-pillar validation strategies, such as knockout/knockdown controls, orthogonal methods, and immunoprecipitation followed by mass spectrometry (IP/MS), to provide higher confidence in antibody specificity [14] [16]. Community efforts and open science initiatives, which share large-scale antibody characterization data openly, are also pivotal for the future of reproducible research [10].

Navigating the critical distinctions between validation, verification, and optimization is a non-negotiable skill for researchers in immunohistochemistry. Validation provides the foundational evidence for a new test, verification ensures an established test works in a new context, and optimization fine-tunes the protocol for optimal results. By adhering to updated guidelines, employing rigorous experimental designs, and leveraging well-characterized reagents, the scientific community can significantly enhance the reliability of IHC data, thereby accelerating drug development and ensuring the integrity of research outcomes.

For antibodies used in immunohistochemistry (IHC), confirming that the antibody binds specifically to its intended target is paramount. This process, known as epitope characterization, lies at the core of antibody validation and ensures that the staining observed in tissue samples is accurate and biologically meaningful. An epitope is the specific region of an antigen recognized by an antibody [17]. Thorough epitope characterization is a critical step in developing reliable IHC biomarkers for both research and clinical decision-making, such as guiding targeted therapies for cancer [1].

This guide objectively compares the performance of various epitope characterization methods, from traditional experimental techniques to modern computational approaches, providing researchers with the data needed to select the right tools for their antibody validation protocols.

Comparative Analysis of Epitope Characterization Methods

The field of epitope characterization offers a diverse toolkit, each method with distinct strengths, limitations, and performance metrics. The table below provides a comparative overview of popular and emerging techniques.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Epitope Characterization Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Typical Application in IHC Validation | Key Performance Metrics | Notable Tools/Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blocking Peptides [18] | Competes with target epitope for antibody binding. | Verification of antibody specificity in IHC. | Qualitative (yes/no) specificity confirmation. | Peptide pre-incubation control [18]. |

| DECODE [19] | High-throughput epitope mapping via mRNA display. | Precise, single amino acid resolution epitope mapping for monoclonal/polyclonal antibodies. | Single amino acid resolution; predicts cross-reactivity. | Applied to develop improved 3D immunostaining [19]. |

| X-ray Crystallography [20] | Determines atomic structure of antibody-antigen complex. | Gold standard for definitive epitope mapping. | Atomic-level resolution. | Laborious and low-throughput [20]. |

| Deep Mutational Scanning (DMS) [20] | High-throughput experimental screening of all possible single-point mutations. | Fine-grained functional epitope mapping. | High-throughput; functional impact data. | Can yield false positives due to allostery or stability effects [20]. |

| AlphaFold 3 (AF3) + AbEMap [20] | AI-based co-folding of Ab-Ag complex and epitope prediction. | In silico epitope prediction when only sequences are known. | ROC AUC: 0.62; PR AUC: 0.22 [20]. | Superior performance among computational methods [20]. |

| AbEMap (Docking-based) [20] | Computational docking and template-based modeling. | In silico epitope prediction with known antigen and antibody structures. | ROC AUC: 0.55; PR AUC: 0.16 [20]. | Antibody-specific prediction [20]. |

| DiscoTope [20] | Machine learning on antigen structure features. | Antibody-agnostic conformational epitope prediction. | ROC AUC: ~0.60 (as reported in original publication) [20]. | Popular antibody-agnostic tool [20]. |

Performance Data and Experimental Validation

Quantitative Performance of Computational Tools

Computational methods for B-cell epitope prediction have evolved significantly, yet their accuracy varies. A recent evaluation on a benchmark set of antibody-antigen complexes revealed that a combined pipeline using AlphaFold 3 for complex structure prediction and AbEMap for epitope analysis achieved the highest accuracy among the methods tested, with a ROC AUC of 0.62 and a PR AUC of 0.22 [20]. This performance was substantially better than docking-based AbEMap (ROC AUC: 0.55) or standalone antibody-agnostic tools like DiscoTope [20]. It is important to note that while these tools provide valuable insights, their predictions still require experimental validation [20].

The Critical Role of Experimental Validation

For IHC, computational predictions are a starting point. Specificity must be confirmed experimentally. A key validation step is the use of blocking peptides, where pre-incubating the antibody with its target peptide should abolish or significantly reduce IHC staining, confirming that the signal is specific [18]. Furthermore, guidelines from the College of American Pathologists (CAP) recommend comparing IHC results with other non-immunohistochemical methods, such as flow cytometry or fluorescent in-situ hybridization, to build confidence in the antibody's performance [3].

Table 2: Key Experimental Validation Protocols for IHC Antibodies

| Validation Protocol | Detailed Methodology | Interpretation of Results for Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| Blocking Peptide Assay [18] | 1. Incubate the primary antibody with a molar excess of the target antigen peptide.\n2. Apply the peptide-antibody mixture to a tissue section alongside an untreated antibody control.\n3. Perform standard IHC staining and compare staining intensity. | A significant reduction or complete loss of staining in the peptide-blocked sample, compared to the control, confirms the antibody's binding is specific to the target epitope. |

| Cell Pellet Transfection [18] [1] | 1. Transfert cell lines (e.g., 293T) to express the target protein.\n2. Create formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) cell pellets from transfected and non-transfected (negative control) cells.\n3. Perform IHC staining. | Specific staining in transfected cells, but not in non-transfected controls, validates target specificity. Weakly positive or negative cells in a partially efficient transfection can help differentiate signal from noise [1]. |

| Western Blot Analysis [18] | 1. Separate protein lysates from positive and negative control cell lines via gel electrophoresis.\n2. Transfer to a membrane and probe with the antibody.\n3. Develop to visualize bands. | Demonstration of a single band at the appropriate molecular weight, with minimal cross-reacting bands, supports specificity. Multiple bands may indicate splice variants or post-translational modifications, not necessarily non-specificity [1]. |

| Comparison with Orthogonal Methods [3] | 1. Test the same biological samples (e.g., cell lines, tissues) using IHC and another method like flow cytometry (for membrane targets) or mass spectrometry.\n2. Correlate the results from the different techniques. | A strong correlation between IHC staining and the results from the orthogonal method builds confidence in the IHC assay's accuracy and specificity. |

Workflow and Logical Framework for Epitope Characterization

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for integrating epitope characterization into a comprehensive antibody validation workflow for IHC.

Diagram 1: Epitope Characterization in IHC Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

A robust epitope characterization and IHC validation pipeline relies on several key reagents and tools. The following table details these essential components.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Epitope Characterization and IHC Validation

| Item | Function in Validation | Specific Examples & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Primary Antibodies | The key reagent that binds the target epitope in IHC. | Select antibodies validated for IHC in FFPE tissues. Look for vendors that provide detailed validation data (e.g., Cell Signaling Technology) [18]. |

| Control Cell Lines | Provide known positive and negative biological controls for specificity testing. | Can be naturally expressing or transfected with the target gene. FFPE cell pellets are ideal for mimicking tissue samples [1]. |

| Blocking Peptides | Synthetic peptides matching the target epitope used to confirm antibody specificity. | Critical for verifying that IHC staining is on-target. Used in peptide competition assays [18]. |

| Tissue Microarrays (TMAs) | Allow high-throughput IHC screening across multiple tissue types or pathologies. | Maximize IHC data while ensuring uniform technical application. Useful for demonstrating antibody performance across a spectrum of tissues [18] [1]. |

| Phospho-specific Antibodies | Detect post-translational modifications like phosphorylation. | Require special tissue handling to preserve labile epitopes. A pan-phospho antibody can help assess tissue sample quality [1]. |

| AI-Based Epitope Prediction Tools | Provide computational insights into epitope location and potential cross-reactivity. | Tools like AlphaFold 3 can predict Ab-Ag complex structures, while others like MUNIS excel at T-cell epitope prediction [17] [20]. |

| High-Throughput Epitope Mapping (DECODE) | Precisely maps epitopes for monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies at single-amino-acid resolution. | Identifies exact binding residues and predicts cross-reactivity against the entire protein database, greatly enhancing reproducibility [19]. |

In the field of diagnostic and research pathology, adherence to established regulatory standards is paramount for ensuring test accuracy, reliability, and patient safety. The Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) and the College of American Pathologists (CAP) accreditation represent two critical components of the quality management landscape for laboratories in the United States [21]. CLIA establishes the federal regulatory baseline for all clinical laboratory testing, while CAP accreditation signifies adherence to more stringent, specialty-specific standards that often exceed CLIA requirements [21]. For researchers and drug development professionals working with immunohistochemistry (IHC) assays, understanding the relationship between these frameworks is essential for developing compliant validation protocols that yield clinically actionable data.

CLIA regulations are overseen by three federal agencies: the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [21]. CMS enforces basic CLIA compliance, while CAP functions as an accreditation organization with "deeming authority," meaning CMS recognizes CAP standards as exceeding basic CLIA requirements [21]. This relationship creates a tiered system where all clinically reporting laboratories must comply with CLIA, but many seek additional CAP accreditation to demonstrate superior quality standards, particularly for complex assays like IHC used in biomarker detection and therapeutic decision-making.

CLIA Requirements and Updates

Fundamental CLIA Structure and Provisions

The Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 established quality standards for all laboratory testing performed on humans in the United States, with regulations found in Part 493 of the Federal Register [21]. CLIA categorizes tests based on complexity (waived, moderate, or high complexity), with increasingly stringent requirements for more complex assays [21]. All IHC assays used for clinical decision-making fall under high-complexity testing, requiring laboratories to meet specific standards for personnel qualifications, quality control, proficiency testing, and validation procedures.

CLIA's fundamental requirement for test validation is outlined in §493.1253, which states that before introducing any new test system, laboratories must demonstrate that performance specifications for accuracy, precision, analytical sensitivity, and analytical specificity are met [22]. However, CLIA does not prescribe specific validation protocols, allowing laboratories flexibility in establishing validation procedures appropriate for their specific methodologies, including IHC.

Recent CLIA Proficiency Testing Updates

A significant update to CLIA proficiency testing requirements took effect on January 1, 2025, implementing new analytical performance (AP) criteria for numerous analytes across chemistry, immunology, endocrinology, toxicology, and hematology [23] [24]. These changes, which were fully implemented by proficiency testing organizations on January 1, 2025, impact many tests relevant to IHC and biomarker analysis.

Table: Select 2025 CLIA Proficiency Testing Acceptance Limits for Relevant Analytes

| Analyte or Test | NEW 2025 CLIA Criteria | Previous Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin A1c | TV ± 8% | None (newly regulated) |

| High-sensitivity C-reactive protein | TV ± 1 mg/L or ± 30% (greater) | None (newly regulated) |

| Alpha-fetoprotein | TV ± 20% or positive/negative | TV ± 3 SD |

| Cancer antigen 125 | TV ± 20% | None (newly regulated) |

| Carcinoembryonic antigen | TV ± 15% or ± 1 ng/dL (greater) | None (newly regulated) |

| Prostate Specific Antigen | TV ± 0.2 ng/mL or 20% (greater) | None (newly regulated) |

| Cell identification | 80% or greater consensus | 90% or greater consensus |

| Estradiol | TV ± 30% | None (newly regulated) |

| Testosterone | TV ± 20 ng/dL or ±30% (greater) | None (newly regulated) |

These updated requirements reflect evolving analytical capabilities and clinical needs, with many analytes newly added to CLIA-regulated testing [23] [24]. Laboratories must ensure their proficiency testing programs align with these updated standards, as performance on these tests is a key component of CLIA compliance.

CAP Accreditation Standards

CAP Accreditation Process and Value

The College of American Pathologists offers a voluntary accreditation program that exceeds basic CLIA requirements through more detailed, specialty-specific standards [21]. CAP accreditation involves a rigorous process where qualified CAP inspectors (practicing laboratory professionals from other CAP-accredited labs) conduct on-site inspections every two years, with self-inspections in alternate years [21]. This peer-based inspection model ensures that assessors possess relevant technical expertise for the specialty areas they are evaluating.

CAP standards are documented in detailed checklists that include both general and specialty-specific requirements, with the Anatomic Pathology checklist containing particularly relevant guidance for IHC laboratories [22]. For drug development professionals and researchers, utilizing CAP-accredited laboratories provides assurance that testing meets the most comprehensive, scientifically-endorsed standards available, which can be particularly valuable for assays supporting regulatory submissions or clinical trial decisions [21].

CAP Guidelines for IHC Assay Validation

In February 2024, CAP updated its "Principles of Analytic Validation of Immunohistochemical Assays" guideline, which provides detailed recommendations for validating IHC assays [3] [25]. A key update includes harmonized validation requirements for all predictive markers, replacing previous variable concordance requirements with a uniform 90% overall concordance standard between the new assay and comparator methods [3] [25]. This streamlined approach applies to all IHC assays, including established biomarkers like estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER2.

The updated CAP guideline introduces several important new recommendations:

- Separate validation for each assay-scoring system combination for predictive markers with distinct scoring systems (e.g., PD-L1, HER2) [3]

- Enhanced validation requirements for cytology specimens fixed differently from standard FFPE tissues, requiring a minimum of 10 positive and 10 negative cases for specimens fixed in alternative fixatives [3]

- Explicit verification requirements for unmodified FDA-approved/cleared assays [3]

These recommendations reflect the evolving complexity of IHC testing, particularly for predictive biomarkers used to guide targeted therapies.

Comparative Analysis: CLIA versus CAP

Table: Key Differences Between CLIA and CAP Requirements

| Aspect | CLIA Regulations | CAP Accreditation |

|---|---|---|

| Legal Status | Federal law mandated for all clinical testing | Voluntary accreditation program |

| Governance | CMS, FDA, and CDC oversight | Professional society with deemed status |

| Specificity | General quality standards | Specialty-specific detailed requirements |

| Inspection Process | CMS or state agency surveyors | Peer-based inspections by practicing laboratory professionals |

| Proficiency Testing | Specified regulated analytes with defined performance criteria | Includes all CLIA-required PT plus additional analytes as specified in checklists |

| Test Validation | Requires demonstration of performance specifications | Provides detailed methodology for validation specific to test type |

| IHC Guidance | General validation requirements | Detailed protocols for IHC validation, including recent updates for predictive markers and cytology specimens |

While CLIA provides the regulatory floor for laboratory testing, CAP accreditation represents a more comprehensive quality framework with specific requirements tailored to different laboratory specialties [21]. For IHC laboratories, CAP guidelines offer crucial specificity for validation approaches that CLIA's general requirements lack. This distinction is particularly important for laboratories implementing complex IHC assays for predictive biomarkers, where CAP provides explicit guidance on validation methodologies, concordance thresholds, and specimen requirements [3] [22].

A critical distinction in terminology exists between "validation" and "verification" in these frameworks. CAP guidelines clarify that when an existing validated IHC assay undergoes specific changes (antibody dilution, vendor change with same clone, or incubation/retrieval times with same method), laboratories need only perform a streamlined "verification" with at least 2 known positive and 2 known negative cases, rather than full re-validation [22]. This distinction provides important efficiency for laboratories implementing minor modifications to established assays.

IHC Validation Protocols and Methodologies

Tiered Antibody Validation Approach

A consensus approach to antibody validation for IHC, proposed by a consortium of academic and pharmaceutical histopathology researchers, recommends a tiered validation system based on evidence of antibody usage [1]. This framework appropriately scales validation requirements based on prior characterization:

- Tier 1: Well-characterized antibodies with substantial high-quality literature evidence require standard validation.

- Tier 2: Established antibodies used in alternative species or unvalidated tissues need intermediate validation.

- Tier 3: Novel antibodies with inconsistent or no literature evidence demand comprehensive validation [1].

This risk-based approach efficiently allocates resources while ensuring sufficient evidence for analytical specificity.

Stepwise Validation Methodology

Comprehensive IHC antibody validation follows a systematic process to establish analytical specificity and sensitivity:

- Step 1: Target Understanding – Conduct comprehensive literature review of target biology, expected expression patterns, and subcellular localization using databases like OMIM, Uniprot, and Genecards [1].

- Step 2: Control Identification – Establish positive and negative control materials, including cell lines with known expression levels, transfected/knockdown systems, and relevant tissue specimens [1] [4].

- Step 3: Method Selection – Choose appropriate detection methods based on expected expression levels, employing commercially validated kits and systematic optimization of retrieval conditions [1].

- Step 4: Specificity Assessment – Demonstrate antibody specificity through Western blotting, cell pellet staining, peptide blocking, and comparison with alternative methods [26] [1].

- Step 5: Tissue Staining – Test antibody performance across a comprehensive panel of tissues (typically 20+ normal and pathologic tissues) at multiple concentrations [4].

- Step 6: Result Comparison – Compare staining patterns with literature expectations and results from antibodies targeting different epitopes of the same antigen [4].

- Step 7: Documentation – Thoroughly document all validation data, including staining protocols, control results, and interpretation criteria [1].

Experimental Design for Validation Studies

Proper experimental design is crucial for generating meaningful validation data. CAP guidelines recommend several comparator models for IHC validation study design, listed here from most to least stringent:

- Comparison with IHC results from cell lines containing known amounts of target protein ("calibrators")

- Comparison with non-immunohistochemical methods (flow cytometry, FISH)

- Comparison with testing results from another laboratory using a validated assay

- Comparison with prior testing of same tissues with validated assay in same laboratory

- Comparison with expected architectural and subcellular localization of antigen [3]

For initial validation of predictive marker assays, the updated CAP guidelines recommend testing a minimum of 10 positive and 10 negative cases for cytology specimens with alternative fixatives, while the overall concordance threshold for all IHC assays is now uniformly set at 90% [3] [25].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Essential Research Reagents for IHC Validation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Antibodies | Monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies targeting specific epitopes | Specific binding to target antigen of interest; monoclonal preferred for specificity |

| Control Cell Lines | Transfected cell lines, knockdown systems, xenografts | Provide known positive/negative controls for specificity assessment |

| Tissue Microarrays | Normal tissues, cancer arrays, multi-tissue panels | Enable comprehensive staining assessment across diverse tissues |

| Detection Systems | HRP-DAB, alkaline phosphatase-Vector Red, polymer systems | Visualize antibody binding with appropriate sensitivity and minimal background |

| Antigen Retrieval | pH-specific buffers, enzymatic retrieval solutions | Reverse formaldehyde-induced epitope masking in FFPE tissues |

| Blocking Reagents | Normal serum, BSA, proprietary blocking solutions | Reduce non-specific background staining |

| Validation Tools | Blocking peptides, isotype controls | Confirm antibody specificity through competition assays |

| Fixation Materials | Neutral buffered formalin, alternative fixatives | Standardize tissue processing conditions |

Successful IHC validation requires appropriate selection of biological materials. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) cell pellets from lines with known expression levels provide excellent controlled specimens for initial validation [26] [1]. For tissue-based validation, comprehensive panels including both normal and pathologic tissues are essential, with attention to potential expression differences across tissue types [4]. The use of tissue microarrays enables efficient staining assessment across multiple tissue types while ensuring consistent technical parameters [1].

Antibody selection requires careful consideration of clone specificity, host species, and recognition of formalin-resistant epitopes. Monoclonal antibodies typically offer superior specificity but may underperform in formalin-fixed tissues, while polyclonal antibodies demonstrate higher success rates in FFPE specimens but may exhibit more non-specific background [4]. For critical applications, antibodies should be validated using multiple complementary methods, such as Western blotting, immunoprecipitation, or genetic approaches (overexpression/knockdown) to confirm target specificity [26] [1].

Practical Implementation Strategies

Navigating Regulatory Requirements

Implementing compliant IHC validation protocols requires understanding how CLIA and CAP requirements interact in practice. Laboratories should:

- Establish a validation master plan that addresses both CLIA's general performance specifications and CAP's IHC-specific guidelines

- Maintain comprehensive documentation for all validation studies, including protocol parameters, raw data, and interpretation criteria

- Implement appropriate quality controls for daily use, reflecting the conditions established during validation

- Participate in relevant proficiency testing programs for all regulated analytes and clinically reported tests

- Conduct regular method verification when modifying existing assays, following CAP's streamlined approach for minor changes [22]

For laboratories developing IHC assays for companion diagnostic applications, additional FDA requirements may apply, typically following Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines and potentially requiring Premarket Approval (PMA) submissions [27]. These regulatory pathways demand more extensive analytical validation than standard CLIA requirements, including multi-site reproducibility studies for IVD kits [27].

Special Considerations for Predictive Biomarkers

Validation of predictive IHC biomarkers (e.g., PD-L1, HER2) requires additional considerations:

- Separate validation for each indication when different scoring systems apply to different tumor types or clinical contexts [3]

- Harmonized concordance thresholds of 90% for all predictive markers, replacing previous variable standards [25]

- Rigorous pathologist training on scoring criteria to ensure consistent interpretation across readers

- Ongoing monitoring of assay performance through quality assurance programs

The updated CAP guidelines specifically address these requirements, emphasizing that laboratories must separately validate each assay-scoring system combination used for predictive markers [3]. This ensures that staining interpretation aligns with clinical decision thresholds established for specific therapeutic contexts.

By understanding and implementing these regulatory frameworks, researchers and drug development professionals can ensure their IHC assays generate reliable, clinically actionable data that meets current regulatory expectations while supporting advancements in personalized medicine.

The Impact of Poor Validation on Research Reproducibility

The reproducibility crisis represents one of the most significant challenges in modern biomedical research, with poorly validated antibodies identified as a major contributing factor. Antibodies are indispensable tools used to detect and characterize proteins across countless research applications, particularly in immunohistochemistry (IHC) where they serve diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic roles [1] [28]. However, substantial evidence reveals that a concerning percentage of commercial antibodies fail to recognize their intended targets specifically, generating unreliable data that undermines research validity and wastes valuable resources [29]. This comprehensive analysis examines the scope of the antibody validation problem, its financial and scientific consequences, and establishes rigorous validation frameworks essential for restoring research reproducibility.

The Scale of the Problem: Quantitative Evidence

Large-scale systematic studies have quantified the alarming rate of antibody failure, providing concrete evidence for what was previously largely anecdotal knowledge within the research community.

Table 1: Large-Scale Antibody Validation Studies

| Study Scope | Failure Rate | Financial Impact | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 614 commercial antibodies for 65 neuroscience targets | >50% failed in one or more applications | $1 billion wasted annually on ineffective antibodies | ~50-75% of proteins covered by at least one high-performing antibody; recombinant antibodies outperformed monoclonal/polyclonal | [29] |

| 2,500+ commercial antibodies from Human Protein Atlas | >50% did not perform as expected in intended assays | Not quantified | Significant variability in antibody performance across different applications | [30] |

| Commercial antibody market analysis | Not specified | $0.375-$1.75 billion wasted yearly on non-specific antibodies | Hundreds of underperforming antibodies were found to have been used in numerous published articles | [29] |

The implications extend beyond financial waste, as these underperforming reagents have permeated the scientific literature. The study examining 614 neuroscience antibodies found that "hundreds of the underperforming antibodies identified in this study were found to have been used in a large number of published articles, which should raise alarm" [29]. This suggests that a substantial portion of published protein research may be based on unreliable antibody data, creating ripple effects through subsequent studies that build upon these flawed foundations.

Consequences of Poor Antibody Validation

Financial and Resource Impacts

The economic burden of poorly validated antibodies extends far beyond the initial purchase price of ineffective reagents. Researchers conservatively estimate that $1 billion is wasted annually on research involving ineffective antibodies, with other analyses suggesting the figure may range from $0.375 to $1.75 billion yearly [29]. These staggering amounts represent not only direct reagent costs but also the substantial investment of researcher time, laboratory materials, and institutional resources dedicated to experiments compromised by unreliable tools.

The resource waste compounds throughout the research pipeline. A single failed antibody can invalidate months of meticulous work, including sample preparation, data collection, and analysis. Perhaps more damaging is the opportunity cost—the potentially valid research questions that went unexplored due to resources being diverted to dead ends created by antibody failures. This misallocation of scarce research funding substantially slows the pace of scientific discovery across multiple fields, particularly in neuroscience and cancer research where antibody-based methods are foundational [29].

Scientific and Reproducibility Impacts

The scientific consequences of poor antibody validation extend beyond financial considerations to the very integrity of research findings. The fundamental requirement of scientific progress—the ability to reproduce and build upon published findings—is severely compromised when different research groups obtain conflicting results due to variable reagent performance rather than true biological differences.

The problem is particularly acute in immunohistochemistry research, where antibodies are used "as a decision making tool to ascertain those patients who are most likely to benefit from treatment" in clinical contexts [1]. When these critical tools are not properly validated, they can lead to misdiagnosis or inappropriate treatment selection. For example, IHC tests determine whether cancer patients receive specific targeted therapies, with PD-L1 IHC testing alone guiding treatment decisions that cost "on average $150,000 per year" per patient [30].

The reproducibility crisis fueled by poor antibody validation also erodes the scientific community's credibility and slows therapeutic development. As noted in one analysis, "the use of poor-quality antibodies is a major factor in the scientific reproducibility crisis" [29]. This crisis manifests when laboratories cannot replicate published findings, when animal studies fail to translate to human therapies, and when clinical trials proceed based on questionable preclinical data. The cumulative effect is a breakdown in the scientific process that depends on verification and sequential advancement of knowledge.

Antibody Validation Frameworks and Protocols

Tiered Validation Approach

A consortium of academic and pharmaceutical researchers has proposed a structured, tiered framework for antibody validation that categorizes antibodies based on existing evidence and dictates appropriate validation rigor [1].

Table 2: Tiered Antibody Validation System

| Tier | Antibody Characterization | Validation Requirements | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | Well-known antibody with high-quality literature evidence | Minimal additional validation required | Antibodies with extensive published data across multiple applications |

| Level 2 | Well-known antibody used in alternative species or unvalidated tissue | Moderate validation for new context | Antibodies validated for human tissue applied to mouse models |

| Level 3 | Unknown antibody with inconsistent or no literature evidence | Comprehensive validation required | Novel antibodies or those with limited characterization |

This risk-based approach allocates resources efficiently while ensuring appropriate rigor. As outlined in the guidelines, the validation process begins with a thorough understanding of the target through literature review and database mining (e.g., OMIM, Uniprot, Genecards), followed by identification of appropriate control cells and tissues, selection of optimal IHC methods, and determination of the required validation level [1].

Stepwise Validation Protocol

For rigorous immunohistochemistry applications, researchers have developed detailed stepwise validation protocols that integrate multiple complementary strategies [30]:

This structured approach ensures systematic assessment of antibody performance. The initial localization check provides early evidence of specificity, while quantitative titration establishes optimal assay conditions [30]. The critical third step employs one or more validation strategies to confirm specificity, with genetic approaches using CRISPR knockout cell lines representing particularly compelling evidence [29] [30]. Finally, reproducibility testing across technical and operational variables ensures robust performance in real-world conditions.

Multipillar Validation Strategies

Leading antibody manufacturers and research consortia have established comprehensive validation frameworks incorporating multiple evidentiary pillars. Cell Signaling Technology's "Hallmarks of Antibody Validation" exemplifies this approach, incorporating six complementary strategies [31]:

- Genetic Strategies: Using CRISPR/Cas9 knockout cell lines to confirm loss of signal

- Orthogonal Validation: Comparing results with non-antibody methods (e.g., in situ hybridization, mass spectrometry)

- Independent Antibodies: Correlating results from multiple antibodies targeting non-overlapping epitopes

- Biological Context: Ensuring expression patterns match expected biology across tissue types

- Recombinant Protein Expression: Testing with purified recombinant target protein

- Immunoprecipitation Followed by Mass Spectrometry: Identifying all proteins pulled down by the antibody

This multi-faceted approach is necessary because "no single assay is sufficient to validate an antibody, including knockout" [31]. Different applications may require different validation strategies, and performance in one application does not guarantee specificity in another.

Recommended Experimental Protocols

Knockout-Based Validation

Genetic knockout validation using CRISPR/Cas9 technology represents the current gold standard for establishing antibody specificity [29] [32]. This method provides compelling evidence by directly linking the genetic presence of the target protein to the antibody-derived signal.

Protocol Overview:

- Cell Line Selection: Identify parental cell lines expressing the target protein using RNA expression databases (e.g., DepMap) with a threshold of 2.5 log2(TPM+1) [29]

- CRISPR Engineering: Generate isogenic knockout cell lines using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing

- Parallel Testing: Perform IHC on both parental and knockout cell lines under identical conditions

- Result Interpretation: Specific antibodies show signal loss in knockout lines while maintaining appropriate staining in parental lines

This approach effectively controls for non-specific binding and off-target effects, providing high-confidence validation when properly executed [29]. The scalability of this method has been demonstrated in studies validating hundreds of antibodies, establishing it as a robust and reproducible validation platform.

Orthogonal Validation Methods

Orthogonal validation employs non-antibody-dependent methods to verify protein expression patterns detected by IHC [30]. This approach provides independent confirmation of antibody specificity through alternative technological platforms.

Key Orthogonal Methods:

- mRNA In Situ Hybridization: Correlates protein detection with mRNA expression patterns in tissue sections

- Mass Spectrometry: Verifies protein identity and presence in sample types

- Western Blotting: Confirms target molecular weight and detects potential splice variants

- Flow Cytometry: Validates cell type-specific expression in suspension

The power of orthogonal validation lies in its technological independence from IHC, reducing the likelihood that both methods would share the same artifacts or failure modes. When antibody-based protein detection aligns with mRNA expression patterns or mass spectrometry results, confidence in antibody specificity increases substantially.

Quantitative Titration and Optimization

Proper antibody titration represents a fundamental but frequently overlooked aspect of validation [30]. Suboptimal concentration represents a common source of poor specificity and reproducibility in IHC.

Optimization Protocol:

- Serial Dilution: Test antibody concentrations spanning at least two full logs (e.g., 1:100 to 1:10,000)

- Tissue Microarray Screening: Use TMAs containing tissues with expected variable target expression

- Quantitative Analysis: Employ quantitative image analysis (e.g., AQUA, HALO, Visiomorph) rather than subjective scoring

- Dynamic Range Assessment: Identify the concentration providing maximal signal-to-noise ratio

- Condition Optimization: Systematically test antigen retrieval buffers and incubation conditions

This quantitative approach establishes optimal assay conditions that maximize sensitivity while minimizing background, ensuring the antibody operates within its linear dynamic range for subsequent validation steps and experimental use.

Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing rigorous antibody validation requires specific reagents and tools designed to address key challenges in specificity verification.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Antibody Validation

| Reagent/Tool | Function in Validation | Key Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Knockout Cell Lines | Gold standard specificity control; confirms signal dependency on target protein | Western blot, IHC, immunofluorescence, flow cytometry | Requires specialized expertise; potential for compensatory mechanisms |

| Isogenic Control Cell Lines | Provide genetically matched positive controls for knockout validation | All antibody applications | Must be carefully characterized to ensure genetic stability |

| Tissue Microarrays (TMAs) | Enable high-throughput screening across multiple tissue types | IHC antibody optimization and validation | Tissue quality and antigen preservation must be verified |

| Recombinant Antibodies | Defined sequence eliminates batch variability; renewable resource | All applications; particularly valuable for long-term studies | Higher initial development cost; limited availability for some targets |

| Positive/Negative Control Tissues | Verify expected staining patterns and absence of non-specific binding | IHC assay development and quality control | Should represent biological contexts relevant to research questions |

| Automated Image Analysis Platforms | Provide objective, quantitative assessment of staining intensity | IHC validation and quantitative studies | Requires standardization and validation of analysis algorithms |

The future of antibody validation points toward increased standardization, transparency, and data sharing. Community-driven databases and open access to validation data will help researchers identify high-performing reagents and avoid problematic antibodies [33]. The growing adoption of recombinant antibodies with defined sequences addresses the batch-to-batch variability inherent in traditional monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies [29] [32].

Digital pathology and artificial intelligence represent promising technological advancements that will enhance validation rigor through automated, quantitative image analysis, reducing the subjectivity that plagues traditional IHC scoring [28]. Integration of these tools with standardized validation protocols will improve reproducibility across laboratories.

In conclusion, the impact of poor antibody validation on research reproducibility is profound and far-reaching, affecting scientific integrity, clinical decision-making, and resource allocation. The implementation of systematic, multi-tiered validation frameworks incorporating genetic, orthogonal, and independent verification strategies is essential to restore reliability to antibody-based research. As the field moves toward standardized validation requirements and increased data transparency, researchers must adopt these rigorous practices to ensure that their findings contribute meaningfully to scientific advancement rather than exacerbating the reproducibility crisis.

Procedural Frameworks: Implementing Rigorous Validation Methods for IHC

{# This guide explores the universal framework of the Five Pillars of Antibody Validation, providing objective performance data and detailed protocols to enhance reproducibility in immunohistochemistry research. #}

In biomedical research, antibodies are indispensable tools for detecting and visualizing proteins in various experimental contexts, including the critical application of immunohistochemistry (IHC). However, their reliability has been called into question by a well-documented reproducibility crisis, largely fueled by poorly validated antibody reagents [34]. Studies have revealed that a significant portion of commercially available antibodies lack sufficient specificity, with one analysis showing over 50% of antibodies for neuroscience-related proteins failing at least one validation test, and a quarter of antibodies used in epigenetic research proving non-specific [34]. The consequences are far-reaching, leading to irreproducible data, scientific retractions, and entire research fields being misdirected [34].

To address this challenge, the International Working Group for Antibody Validation (IWGAV) established a standardized scientific framework in 2016 [35]. This framework, universally known as the "Five Pillars of Antibody Validation," provides a robust set of strategies to confirm that an antibody binds specifically to its intended target [36] [37]. This guide details these five pillars, provides comparative data on their performance, and outlines specific experimental protocols to empower researchers in their IHC workflow.

The Five Pillars: A Detailed Comparative Analysis

The IWGAV's five pillars offer complementary approaches for demonstrating antibody specificity. Each method has distinct strengths, limitations, and ideal use cases, making them suited for different experimental scenarios [35]. The table below provides a comprehensive comparison.

| Validation Pillar | Core Principle | Key Advantages | Inherent Limitations | Suitability for IHC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Genetic Strategies [35] [34] | Compare signal in wild-type vs. genetically modified (KO/KD) cells/tissues. | Considered a "gold-standard"; provides a true negative control [35]. | Not universal; lethal for essential genes; KD is transient [35] [34]. | High (if viable KO/KD tissue is available) |

| 2. Orthogonal Strategies [35] [38] | Correlate antibody-derived data with an antibody-independent method (e.g., transcriptomics, proteomics). | Can be high-throughput; leverages existing omics data [35]. | mRNA-Protein correlation can be weak; data interpretation can be challenging [35]. | Medium (depends on quality of orthogonal data for tissues) |

| 3. Independent Antibody Strategies [35] [36] | Compare staining patterns of ≥2 antibodies targeting different epitopes on the same protein. | Simple verification; straightforward results [35]. | Risk of correlated false-positives; requires multiple validated antibodies [35] [34]. | High (highly recommended for IHC) |

| 4. Expression of Tagged Proteins [35] [39] | Compare antibody signal against a tagged version of the target (e.g., GFP, c-Myc). | Selective for the target; good for overexpression studies. | Overexpression can cause artifactual localization; tag may alter protein function [35]. | Medium (can confirm specificity but not native context) |

| 5. Immunoprecipitation-Mass Spectrometry (IP-MS) [35] [40] | Identify all proteins bound by an antibody using IP followed by MS. | Identifies the true target and off-targets; can reveal protein complexes [40]. | Technically challenging; not all antibodies work for IP; data can be complex to interpret [35]. | Low (inherently non-spatial, but validates specificity) |

A Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of the five pillars relies on key reagents. The table below lists essential tools referenced in this guide.

| Research Reagent / Tool | Primary Function in Validation | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| KO Cell Lines [35] | Provide a true negative control for genetic validation (Pillar 1). | Ready-made lines accelerate workflow; ensure genetic modification is complete. |

| siRNA/shRNA [34] | Knock down target gene expression for genetic validation (Pillar 1). | Transient effect; incomplete knockdown can leave residual signal. |

| Recombinant Antibodies [35] [39] | Provide a defined, consistent reagent for independent antibody strategies (Pillar 3) and other pillars. | High batch-to-batch consistency; superior for long-term study reproducibility. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Systems [34] | Create permanent knockout cell lines for the most robust genetic validation (Pillar 1). | Requires molecular biology expertise; potential for off-target genomic edits. |

| Tag-Specific Antibodies [35] | Detect expressed tagged proteins (e.g., GFP, c-Myc) for tagged protein validation (Pillar 4). | Crucial for confirming expression and localization of the tagged construct. |

Experimental Protocols for Pillar Implementation

Protocol 1: Genetic Validation (Knockout/Knockdown)

This protocol is widely considered the gold standard for establishing antibody specificity [35].

- Step 1: Cell Line Selection. Choose a cell line that endogenously expresses the target protein at a detectable level.

- Step 2: Genetic Modification.

- Step 3: Sample Preparation. Culture both wild-type and KO/KD cells. Prepare cell pellets for IHC embedding and sectioning, or generate lysates for Western blotting as an initial specificity check [41].

- Step 4: IHC Staining and Analysis. Perform IHC on paired tissue sections (wild-type vs. KO/KD) using standardized conditions. A specific antibody will show a clear and significant reduction in signal in the KO/KD sample compared to the wild-type control [39].

Protocol 2: Orthogonal Validation using Transcriptomics

This method validates antibody specificity by comparing its staining pattern with an antibody-independent measure of target presence [38].

- Step 1: Tissue Panel Selection. Assemble a panel of at least 3-5 tissue samples with known, variable expression levels of the target protein's mRNA, as determined by databases like NCBI Gene or the Human Protein Atlas [34] [38].

- Step 2: IHC Staining. Perform IHC on all tissue samples in the panel using the same protocol.

- Step 3: Quantitative Analysis.

- Quantify the IHC signal (e.g., using an H-score or percentage of positive cells) for each tissue.

- Obtain the corresponding mRNA expression values (e.g., TPM - Transcripts Per Million) for the target gene from transcriptomic databases for the same tissues.

- Step 4: Correlation Assessment. Plot the quantitative IHC scores against the mRNA expression values. A positive Pearson correlation coefficient (ideally >0.5) across the sample set supports the antibody's specificity [38].

Protocol 3: Independent Antibody Validation

This straightforward strategy uses multiple antibodies to build confidence in the observed staining pattern [36].

- Step 1: Antibody Selection. Source at least two independent antibodies that target non-overlapping epitopes on the same protein. Recombinant antibodies are ideal for this purpose due to their high consistency [35].

- Step 2: Parallel Staining. Perform IHC on serial sections of the same tissue sample(s) using each independent antibody under their respective optimized conditions.

- Step 3: Pattern Comparison. Analyze the stained slides for concordance in the cellular localization, sub-cellular distribution, and expression levels of the signal across different tissue structures. Consistent results from multiple antibodies strongly indicate specificity [34].

The logical relationship and application context of these three core validation protocols within an IHC research workflow can be summarized as follows:

Discussion & Best Practices for IHC

For IHC research, no single pillar is sufficient to claim universal validation. The IWGAV recommends using multiple strategies to build a compelling case for antibody specificity [40]. Based on the comparative analysis:

- Genetic strategies (Pillar 1) provide the most definitive evidence if a viable KO tissue model is available.

- Independent antibody validation (Pillar 3) is one of the most practical and highly recommended approaches for IHC, as it directly confirms the expected staining pattern.

- Always include appropriate positive and negative control tissues in every IHC experiment [36].

- Recognize that validation is application-specific. An antibody validated for Western blotting may not work in IHC due to differences in epitope accessibility resulting from formalin fixation and antigen retrieval [41].

The scientific community is increasingly prioritizing antibody validation, with many leading journals and funding agencies requiring detailed validation data. By adopting this universal framework, researchers can generate more reliable and reproducible data, ultimately accelerating the discovery of new biological mechanisms and therapeutic targets.

Antibody validation is a critical process in immunohistochemistry (IHC) research that ensures the accuracy, reproducibility, and reliability of experimental results. This process confirms that an antibody specifically binds to its intended target with minimal cross-reactivity, providing confidence in the data generated [34]. The fundamental principle of antibody validation involves demonstrating that you get a specific signal for your intended target in a given application, going beyond simple detection to provide evidence of minimal off-target binding [34].

The International Working Group on Antibody Validation (IWGAV) has established a framework of five conceptual pillars to guide researchers in thorough antibody characterization [40]. These pillars provide a structured approach to validation, emphasizing that multiple lines of evidence are often necessary to truly confirm antibody specificity for a particular application. The need for rigorous validation is underscored by documented cases where non-specific antibodies have led to paper retractions and have misdirected entire research fields, such as the early work on oestrogen receptor β where only one of thirteen tested antibodies proved specific for IHC [34].

Within clinical and diagnostic applications, organizations like the College of American Pathologists (CAP) provide specific guidelines for analytical validation of IHC assays. The 2024 guideline update affirms and expands on previous recommendations, providing specific requirements for validating predictive markers with distinct scoring systems and offering new guidance for IHC performed on cytology specimens [3]. These guidelines represent the evolving standards in the field, ensuring accuracy and reducing variation in IHC laboratory practices.

Comprehensive Comparison of Validation Strategies

The Five Pillars of Antibody Validation

The IWGAV's five pillars provide a comprehensive framework for antibody validation, each offering distinct advantages and limitations. Genetic strategies involve using knockout or knockdown controls to demonstrate signal loss when the target gene is absent [32]. Orthogonal strategies employ antibody-independent methods to quantify target expression across samples and correlate these findings with antibody-based detection [34]. Independent antibody strategies utilize multiple antibodies recognizing different epitopes on the same target to confirm specificity through consistent results [32]. Tagged protein expression involves modifying the endogenous target gene to include affinity or fluorescent tags, then comparing signals from anti-tag antibodies and the test antibody [40]. Immunoprecipitation with mass spectrometry (IP-MS) identifies proteins captured by the antibody through mass spectrometry, confirming the target and revealing potential off-target interactions [40].

Comparative Analysis of Validation Methods

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Antibody Validation Strategies

| Validation Method | Key Principle | Specificity Confirmation | Best Applications | Technical Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Strategies | Signal reduction in KO/KD systems | High - demonstrates dependency on target presence | Wide range including WB, IHC, ICC, flow cytometry [32] | Not suitable for essential genes; cell line-specific results [34] |

| Orthogonal Strategies | Correlation with antibody-independent quantification | Medium - supports but doesn't definitively prove specificity | Applications where orthogonal data exists (transcriptomics, proteomics) [34] | Protein/RNA expression may not correlate; requires existing data [34] |