Direct, Indirect, and Sandwich ELISA: A Comprehensive Comparison for Researchers

This article provides a detailed comparative analysis of three core ELISA formats—Direct, Indirect, and Sandwich—tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Direct, Indirect, and Sandwich ELISA: A Comprehensive Comparison for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a detailed comparative analysis of three core ELISA formats—Direct, Indirect, and Sandwich—tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, methodological steps, and specific applications for each variant. The scope extends to practical guidance on troubleshooting common issues, optimizing assay performance, and validating results through a critical comparison of sensitivity, specificity, and cost-effectiveness. The objective is to serve as a definitive guide for selecting and implementing the most appropriate ELISA methodology for diverse research and diagnostic goals.

ELISA Fundamentals: Principles, History, and Core Concepts

What is an ELISA? Defining the Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) is a fundamental immunochemical biochemical assay used to detect and quantify substances such as peptides, proteins, antibodies, and hormones in complex biological samples [1] [2]. The method is based on the principle of detecting antigen-antibody interactions, where an enzyme-linked conjugate reacts with a substrate to produce a measurable signal, typically a color change [3] [2]. First developed in the 1970s, ELISA has become a cornerstone technique in research and diagnostic laboratories worldwide due to its high sensitivity and specificity [2].

This guide provides an objective comparison of the four main ELISA variants—direct, indirect, sandwich, and competitive—to help researchers select the optimal method for their specific applications.

Core Principles and Components of an ELISA

At its core, ELISA depends on the highly specific binding between an antibody and its target antigen. The assay is typically performed on a solid phase, such as a 96-well polystyrene microplate, to which antigens or antibodies are immobilized [1] [2]. This solid-phase design facilitates the separation of bound and unbound materials through simple washing steps, making ELISA robust even for crude sample preparations [1].

The key components essential for any ELISA protocol include [2]:

- Solid Phase: Usually a 96-well microplate, which provides a surface for immobilizing the target molecule.

- Capture Molecule: Either an antigen or an antibody that is immobilized to the solid phase to "capture" the analyte of interest from the sample.

- Detection Antibody: An antibody that binds specifically to the captured analyte. This antibody is often linked (conjugated) to an enzyme such as Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) or Alkaline Phosphatase (AP).

- Substrate: A chemical compound that is converted by the enzyme into a detectable product, leading to a colorimetric, fluorescent, or chemiluminescent signal.

- Signal Measurement: The intensity of the final signal is measured using a plate reader and is proportional to the amount of analyte in the sample.

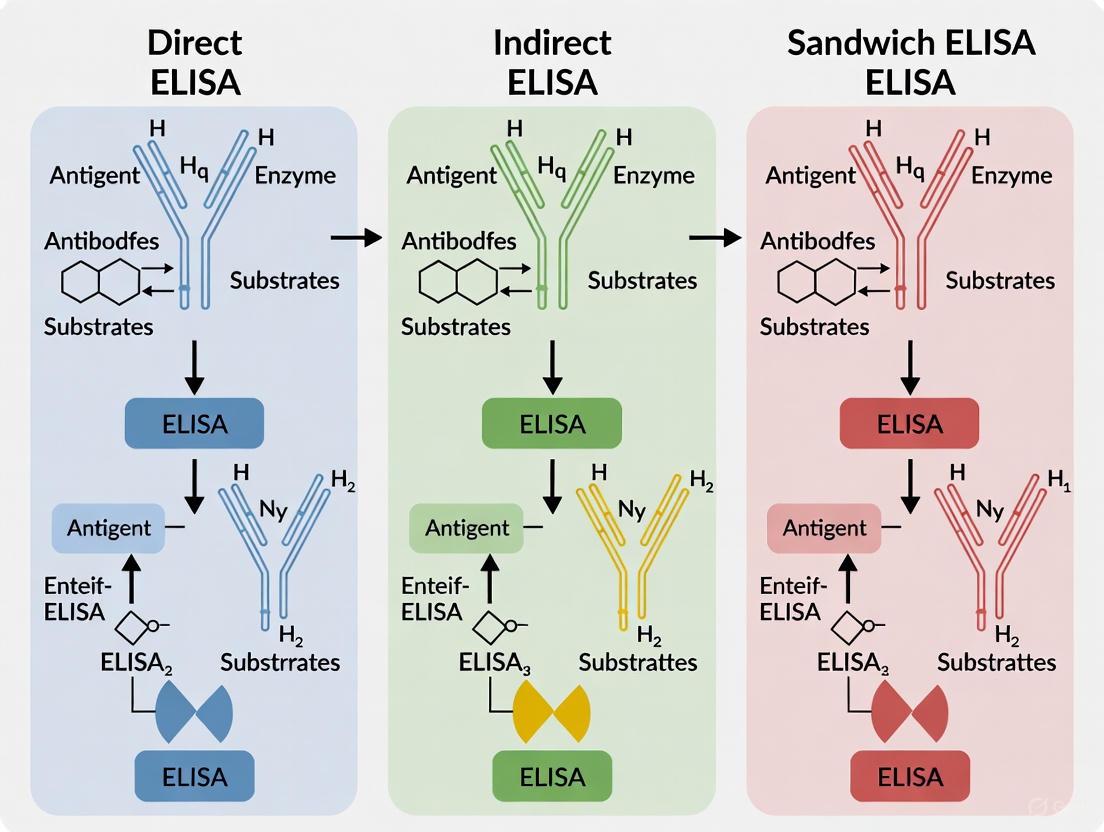

The following diagram illustrates the general logical relationship and workflow common to all ELISA types, from sample immobilization to signal detection.

Comparative Analysis of Major ELISA Types

ELISA methods are primarily categorized into four types, each with distinct mechanisms, advantages, and limitations. The table below provides a structured, quantitative comparison to guide your selection.

| ELISA Type | Detection Strategy | Sensitivity | Specificity | Steps Required | Best For / Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct ELISA [4] [5] | Enzyme-labeled primary antibody binds directly to the immobilized antigen. | Low (no signal amplification) [5]. | High (avoids cross-reactivity from secondary antibodies) [4]. | Fewest (fewer steps, faster protocol) [4] [5]. | Analyzing antigen-antibody immunoreactivity [5]. |

| Indirect ELISA [4] [5] | Unlabeled primary antibody binds antigen, then is detected by an enzyme-labeled secondary antibody. | High (signal amplification via multiple secondary antibodies binding to a single primary) [4] [5]. | Moderate (potential for cross-reactivity from secondary antibody) [4] [5]. | More than Direct (additional incubation and wash step) [5]. | Detecting and quantifying total antibody levels in serum [3] [5]. |

| Sandwich ELISA [6] [4] | Antigen is "sandwiched" between a capture antibody and a detection antibody. | Very High (2–5 times more sensitive than direct/indirect) [5]. | Very High (requires two specific antibodies for a single antigen) [4] [5]. | Most (requires careful optimization of matched antibody pairs) [4] [5]. | Measuring complex or impure samples without antigen purification (e.g., cytokines in cell culture media) [4] [5]. |

| Competitive ELISA [4] [5] | Sample antigen and labeled reference antigen compete for a limited number of antibody-binding sites. | Moderate (overall sensitivity and specificity are lower) [4]. | Moderate | Highly flexible (can be based on direct, indirect, or sandwich formats, but often complex) [5]. | Detecting small antigens or when only one specific antibody is available [3] [5]. |

The following diagram visualizes the fundamental differences in the antigen-antibody binding strategies for each of the four main ELISA types.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducible and high-quality results, adherence to standardized protocols is critical. Below are the detailed step-by-step methodologies for the most common ELISA formats.

Sandwich ELISA Protocol

The sandwich ELISA is renowned for its high sensitivity and specificity and is widely considered the gold standard for quantitative protein detection [3]. The following workflow details its key steps.

Step-by-Step Procedure [6] [3] [1]:

- Coating: Dilute the capture antibody in a coating buffer (e.g., carbonate-bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.4 or phosphate-buffered saline [PBS], pH 7.4) to a concentration typically between 2-10 μg/mL. Add the solution to a polystyrene microplate (≥ 100 μL/well for a 96-well plate). Incubate for several hours at 37°C or overnight at 4°C.

- Blocking: Discard the coating solution. Add a blocking buffer (e.g., 1-5% BSA, non-fat dry milk, or casein in PBS) to cover all unsaturated binding sites on the plastic surface. Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature. Wash the plate 2-3 times with a wash buffer (e.g., PBS or Tris-buffered saline containing a mild detergent like 0.05% Tween 20).

- Sample Incubation: Add the sample or antigen standard, diluted in blocking or sample buffer, to the wells. Incubate for at least 1-2 hours at room temperature to allow the antigen to be captured by the immobilized antibody. Wash as in Step 2 to remove unbound antigens and other sample components.

- Detection Antibody Incubation: Add the enzyme-conjugated detection antibody, specific to a different epitope on the antigen, diluted in blocking buffer. Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature. Wash thoroughly as before to remove any unbound detection antibody.

- Signal Development: Add the enzyme substrate solution (e.g., TMB for HRP). Incubate in the dark for 15-30 minutes, allowing color development.

- Signal Measurement: Stop the enzyme-substrate reaction by adding an acidic stop solution (e.g., 1M H₂SO₄ for TMB, which changes the color from blue to yellow). Immediately measure the absorbance (Optical Density, OD) of each well using a plate reader at the appropriate wavelength (e.g., 450 nm for TMB).

Competitive ELISA Protocol

Competitive ELISA is particularly useful for detecting small molecules or when only one specific antibody is available [3] [5].

Step-by-Step Procedure [4] [1]:

- Coating: Coat the microplate with a known amount of purified antigen (or the specific antibody, depending on the format). Incubate and block as described in the sandwich ELISA protocol.

- Competition Reaction: Pre-incubate a constant amount of the enzyme-labeled antibody (or labeled antigen) with the sample containing the unknown antigen. Alternatively, add both the labeled reagent and the sample simultaneously to the coated plate. During this incubation, the antigen in the sample (unlabeled) and the immobilized antigen (or the labeled antigen) compete for binding to the limited number of antibody-binding sites.

- Washing: Wash the plate to remove any unbound components, including the unbound labeled antigen-antibody complexes.

- Signal Development and Measurement: Add substrate and measure the signal as described previously. The key differentiator is that the signal intensity is inversely proportional to the concentration of the antigen in the sample. A higher antigen concentration in the sample leads to less labeled reagent being bound and, consequently, a weaker signal.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Establishing a reliable ELISA requires a suite of high-quality reagents and equipment. The following table details the essential materials and their functions.

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Critical Function in the Assay |

|---|---|---|

| Solid Phase [1] [2] | 96- or 384-well polystyrene microplates | Provides the solid surface for immobilizing the capture molecule (antigen or antibody). |

| Capture & Detection Molecules [3] [1] | Monoclonal/polyclonal antibodies, purified antigens | Key reagents that provide the assay's specificity by binding to the target analyte. |

| Enzyme Conjugates [1] [2] | Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP), Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) | Enzymes linked to antibodies; catalyze the conversion of substrate to a detectable signal. |

| Substrates [1] [2] | TMB (3,3',5,5'-Tetramethylbenzidine), pNPP (para-Nitrophenyl Phosphate) | Chemicals converted by enzyme conjugates to produce a colorimetric, fluorescent, or chemiluminescent signal. |

| Buffers [1] | Coating buffer (e.g., carbonate, PBS), Blocking buffer (e.g., BSA, casein), Wash buffer (e.g., PBS-Tween) | Enable proper immobilization, reduce non-specific background, and remove unbound material. |

| Laboratory Equipment [6] [2] | ELISA plate reader (spectrophotometer), plate washer, micropipettes | Precisely dispense reagents, automate washing steps, and accurately quantify the output signal. |

The selection of an appropriate ELISA format is a critical determinant of experimental success. The direct ELISA offers simplicity and speed, while the indirect format provides enhanced sensitivity and flexibility. The sandwich ELISA remains the gold standard for specificity and sensitivity in quantifying proteins from complex mixtures, and the competitive ELISA is the method of choice for small molecules or limited reagent availability.

By understanding the comparative strengths, weaknesses, and specific protocols of each method, researchers and drug development professionals can make an informed choice, ensuring robust, reliable, and meaningful data generation in both basic research and clinical diagnostics.

The Radioimmunoassay Revolution and the Emergence of ELISA

The development of radioimmunoassay (RIA) in the 1950s represented a breakthrough in biochemical measurement, enabling scientists to quantify hormones, drugs, and other biologically active substances with unprecedented sensitivity. This method utilized radioactive isotopes as labels to detect antigen-antibody interactions, allowing for the detection of extremely low concentrations of analytes in complex biological fluids [7]. For decades, RIA remained the gold standard for sensitive detection in clinical and research settings.

However, growing concerns about the health risks and regulatory burdens associated with handling radioactive materials created demand for safer alternatives [8]. This need catalyzed the development of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in the 1960s and early 1970s, pioneered by researchers including Engvall, Perlmann, Van Weemen, and Schuurs [2] [9]. The fundamental innovation was replacing radioactive labels with enzyme conjugates that could generate measurable color changes when exposed to appropriate substrates [9]. This transition from radioactivity to enzymatic detection established a new paradigm in immunoassays—one that maintained high sensitivity while eliminating radiation hazards.

A pivotal 1983 study directly compared both methods for detecting antibodies to chromatin components, finding that RIA could detect a human test antiserum at dilutions up to 1:102,400, compared to only 1:3,200 for ELISA, demonstrating RIA's superior sensitivity at the time but also highlighting ELISA's potential as a viable, safer alternative [10]. The first ELISA methodologies employed chromogenic reporters, but the technique has since evolved to incorporate fluorogenic, quantitative PCR, and electrochemiluminescent reporters [9]. The most recent developments include nanoparticle-based reporters that generate color signals visible to the naked eye [9].

Comparative Analysis of Immunoassay Techniques

The transition from RIA to ELISA represented a significant advancement, though each method maintains distinct advantages depending on application requirements.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Immunoassay Platforms

| Assay Type | Detection Principle | Sensitivity | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radioimmunoassay (RIA) | Radioactive isotopes | Very High [10] [7] | High sensitivity for low analyte levels [7] | Radioactive hazards; specialized handling/equipment [7] |

| Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) | Enzyme-colorimetric reaction | High [11] [9] | Cost-effective; safer; high-throughput capability [7] | Generally lower sensitivity than RIA [10] |

| Chemiluminescent Immunoassay (CLIA) | Enzyme-chemical luminescence | Very High [7] | Broad dynamic range; automation friendly [7] | Higher cost; specialized equipment [7] |

| Fluoroimmunoassay (FIA) | Fluorescent compounds | Variable [7] | Fast analysis; highly sensitive with specific probes [7] | Sample matrix interference; limited dynamic range [7] |

While RIA demonstrated superior sensitivity in early comparisons, modern ELISA technologies have narrowed this gap through various amplification systems while offering superior safety profiles and operational convenience. A critical advantage of ELISA over Western blot is its completely quantitative results compared to the semi-quantitative nature of Western blots [11].

Modern ELISA Formats: Principles, Protocols, and Performance Characteristics

The evolution of ELISA technology has produced four principal formats, each with distinct mechanisms and applications suited to different experimental needs.

Direct ELISA

The simplest ELISA format involves immobilizing the antigen directly onto the microplate surface, followed by incubation with an enzyme-conjugated primary antibody that binds specifically to the target antigen [11] [9]. After washing to remove unbound antibody, substrate is added to produce a measurable color change.

Key Protocol Steps:

- Coat microplate with antigen sample (1-2 hours at 37°C or overnight at 4°C)

- Block remaining binding sites with BSA or other proteins (1-2 hours at room temperature)

- Add enzyme-conjugated primary antibody (1-2 hours at room temperature)

- Wash plate to remove unbound antibody

- Add enzyme substrate and measure color development [9] [12]

Advantages: Rapid protocol with fewer steps; eliminates secondary antibody cross-reactivity [11] [12] Disadvantages: Potentially lower sensitivity; higher background from sample proteins; requires labeled primary antibodies for each target [11] [9]

Indirect ELISA

This format introduces an amplification step to increase sensitivity. The antigen is immobilized on the plate, followed by incubation with an unlabeled primary antibody. A secondary antibody conjugated with an enzyme is then added, which binds to the primary antibody [11] [9].

Key Protocol Steps:

- Coat microplate with antigen

- Block nonspecific sites

- Add specific primary antibody

- Add enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody

- Wash and add substrate for detection [9]

Advantages: Enhanced sensitivity through signal amplification; versatile—same labeled secondary can detect various primary antibodies; preserves immunoreactivity of primary antibody [11] [12] Disadvantages: Potential for cross-reactivity with secondary antibody; additional incubation step required [11] [12]

Sandwich ELISA

As the most sensitive ELISA format, this technique captures the target antigen between two specific antibodies—a capture antibody immobilized on the plate and a detection antibody that completes the "sandwich" [11] [9]. This format requires carefully matched antibody pairs that recognize different epitopes on the target antigen.

Key Protocol Steps:

- Coat plate with capture antibody (overnight at 4°C)

- Block plate with BSA (1-2 hours at room temperature)

- Add sample containing target antigen (90 minutes at 37°C)

- Add primary detection antibody (1-2 hours at room temperature)

- Add enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody (1-2 hours at room temperature)

- Wash and add substrate [9]

Advantages: Highest sensitivity and specificity; compatible with complex samples [11] [12] Disadvantages: Time-consuming protocol; requires matched antibody pairs [11] [9]

Competitive ELISA

This format is particularly useful for detecting small molecules with single epitopes. The sample antigen and labeled reference antigen compete for binding to a limited amount of capture antibody. The signal produced is inversely proportional to the amount of antigen in the sample [11] [12].

Advantages: Effective for small molecules; requires less sample purification [11] [12] Disadvantages: Lower specificity; requires conjugated antigen [11]

Experimental Comparisons: Performance Variations Across Commercial ELISA Kits

Recent comparative studies highlight significant performance differences between commercial ELISA kits, emphasizing the importance of careful kit selection and validation.

Corticosterone Measurement in Serum Samples

A 2017 study compared four commercial ELISA kits for quantifying corticosterone in rat serum [8]. The same serum samples yielded significantly different values across kits, with the Arbor Assays kit measuring 357.75 ± 210.52 ng/mL compared to 40.25 ± 39.81 ng/mL for the DRG-5186 kit [8]. Despite high correlations between kits, the absolute concentration values varied substantially, indicating that relative differences within studies may be more reliable than absolute values across different kits [8].

Detection of Bordetella pertussis Antibodies

A recent comparison of six commercial ELISA kits and one in-house assay for detecting anti-pertussis antibodies revealed marked variations in sensitivity and specificity [13]. When testing 40 serum samples, IgA antibodies were detected in 27.5% of samples with the Savyon kit, 25.0% with Euroimmun, 20.0% with the in-house assay, but only 5.0% with the TestLine kit [13]. The study attributed these discrepancies to differences in antigen purity, calibration standards, and cutoff values between manufacturers [13].

SARS-CoV-2 Antibody Detection in Animal Sera

A 2025 evaluation of three ELISA kits for detecting SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in multiple animal species demonstrated that kits targeting the receptor binding domain (RBD) outperformed those detecting nucleoprotein antibodies [14]. ELISA-1 (RBD-targeting) showed the highest diagnostic performance, while ELISA-3 (nucleoprotein-targeting) demonstrated lower sensitivity for detecting seropositive animals [14]. This highlights how antigen choice significantly impacts assay performance, especially across species.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ELISA

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Solid Phase | 96-well polystyrene microplates [2] [12] | Protein binding capacity >400ng/cm²; low CV (<5%) critical for reproducibility [12] |

| Coating Buffers | Carbonate-bicarbonate (pH 9.4), PBS (pH 7.4) [12] | Optimal pH conditions for antigen/antibody immobilization |

| Blocking Agents | BSA, ovalbumin, aprotinin, animal sera [9] | Cover unsaturated binding sites to minimize nonspecific background |

| Detection Enzymes | Horseradish peroxidase (HRP), Alkaline phosphatase (AP) [2] [9] | Generate measurable signals; HRP most common with multiple substrate options |

| Enzyme Substrates | TMB (colorimetric), CDP-Star (chemiluminescent) [9] [12] | Convert enzyme activity to detectable signals; choice affects sensitivity |

| Stop Solutions | HCl, H₂SO₄, NaOH [2] | Halt enzyme-substrate reaction at optimal timepoint |

The evolution from RIA to modern ELISA represents a paradigm shift in immunoassay technology, balancing the imperative for sensitive detection with practical considerations of safety, cost, and throughput. While RIA maintains advantages for certain applications requiring ultra-sensitive detection, ELISA has become the workhorse of modern diagnostics and research due to its versatility, safety profile, and continuous technical improvements.

Current trends suggest ELISA technology will continue evolving toward increased automation, integration with digital platforms, and enhanced sensitivity through novel signal amplification techniques [15]. The 2025 marketplace features diverse providers specializing in different applications, from high-throughput clinical screening to specialized research applications [15]. Future developments will likely focus on multiplexing capabilities and miniaturization to meet growing demands for comprehensive biomarker profiling from limited sample volumes [15].

For researchers and drug development professionals, selection of ELISA formats and commercial kits requires careful consideration of target analyte characteristics, required sensitivity, sample matrix effects, and intended application. The substantial variability between commercial kits underscores the necessity of thorough validation using appropriate standards and controls to ensure data reliability and reproducibility across laboratories.

The Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) is a foundational technique in biomedical research and clinical diagnostics, enabling the detection and quantification of soluble targets like peptides, proteins, antibodies, and hormones. [12] Its operation depends on the precise interplay of four core components: the solid-phase plate, antibodies, enzymes, and substrates. [2] The solid phase, typically a 96-well microplate, serves as the platform for immobilizing the assay reactants. [2] [9] Antibodies provide the critical specificity required to identify the target molecule from a complex mixture. [12] Finally, enzyme and substrate pairs generate a measurable signal, such as a color change, that is proportional to the amount of target present. [2] [9] The quality and compatibility of these components directly determine the performance of an ELISA, impacting its sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these core components, offering experimental data and protocols to inform their selection for various research applications, particularly within the context of comparing direct, indirect, and sandwich ELISA formats.

Comparative Analysis of Core Components

Solid-Phase Plates

The solid-phase plate is the physical foundation of the ELISA, providing a surface for the immobilization of antigens or antibodies. The choice of plate material and its surface properties are crucial for maximizing the assay's binding capacity and consistency.

- Materials and Binding: The most common materials are polystyrene, polyvinyl, and polypropylene. [2] Proteins bind to these plastics via hydrophobic interactions. [12] Polystyrene is the most frequently used due to its excellent optical clarity for colorimetric detection and high protein-binding capacity, typically exceeding 400 ng/cm². [12]

- Plate Selection: Clear polystyrene plates are standard for colorimetric detection. For fluorescent or chemiluminescent signals, black or white opaque plates are used to minimize background interference or to enhance light signal capture, respectively. [12]

- Performance Metrics: A key specification is the coefficient of variation (CV) for protein binding, which should be low (<5% is preferred) to ensure well-to-well and plate-to-plate reproducibility. [12] Imperfections or scratches in the plastic can cause significant aberrations in data acquisition. [12]

Table 1: Comparison of Solid-Phase Plate Properties

| Property | Polystyrene | Polyvinyl | Polypropylene |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common Use | Standard colorimetric ELISA | Similar to polystyrene | Specialized applications |

| Optical Clarity | High (clear) | Variable | Often opaque |

| Protein Binding Capacity | High (>400 ng/cm²) [12] | High | High |

| Typical CV | <5% (preferred) [12] | Information Missing | Information Missing |

| Best For | Colorimetric detection; general use | General use | Fluorescent/Chemiluminescent detection |

Antibodies

Antibodies are the targeting molecules of ELISA, defining its specificity. Their selection and configuration vary significantly between the main ELISA formats.

- Direct vs. Indirect Detection: In a direct ELISA, a single enzyme-conjugated primary antibody is used, making the protocol faster and eliminating potential cross-reactivity from a secondary antibody. [11] [12] However, it is less sensitive, and conjugating primary antibodies is time-consuming and expensive. [12] [16] In an indirect ELISA, an unlabeled primary antibody binds the antigen, and is then detected by an enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody. This allows for signal amplification (as multiple secondaries can bind a single primary) and greater flexibility, as the same labeled secondary can be used with various primary antibodies. [12] [17] The trade-off is an increased risk of cross-reactivity and a longer protocol. [11] [16]

- Sandwich ELISA Pairs: The sandwich ELISA requires two antibodies that bind to distinct, non-overlapping epitopes on the target antigen. [18] One serves as the capture antibody (immobilized on the plate) and the other as the detection antibody. [11] [18] This format provides the highest specificity and sensitivity and is ideal for complex samples, as non-target material can be washed away after the capture step. [11] [12] [17] The main challenge is the need for a "matched pair" of antibodies that do not interfere with each other's binding. [9] [12]

- Antibody Types: Monoclonal antibodies offer high specificity to a single epitope, making them ideal for sandwich assays. [18] Polyclonal antibodies, which recognize multiple epitopes, can increase sensitivity but may have higher cross-reactivity. [18] Recombinant antibodies are increasingly favored for their superior reproducibility and minimal batch-to-batch variation. [18]

Table 2: Antibody Roles in Different ELISA Formats

| ELISA Format | Primary Antibody | Secondary Antibody | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | Enzyme-conjugated | Not used | Single, labeled antibody; simple but less sensitive. [11] [12] |

| Indirect | Unlabeled | Enzyme-conjugated | Signal amplification; flexible but potential for cross-reactivity. [12] [17] |

| Sandwich | Capture antibody (unlabeled) | Detection antibody (may be conjugated or detected by a tertiary conjugate) | Two antibodies for high specificity; requires matched pairs. [9] [18] |

Enzymes and Substrates

The enzyme-substrate system is the signaling engine of the ELISA, converting the antibody-antigen binding event into a quantifiable signal.

- Common Enzymes: The two most widely used enzymes are Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) and Alkaline Phosphatase (AP). [9] [12] HRP is smaller (44 kDa) and has a faster catalytic rate, while AP is known for its high stability. [2] [9] Other enzymes like β-galactosidase are used less frequently. [12]

- Substrates and Detection: The choice of substrate depends on the required sensitivity and the detection instrument available (spectrophotometer, fluorometer, or luminometer). [12]

- Colorimetric: For HRP, TMB (3,3',5,5'-Tetramethylbenzidine) is a common chromogenic substrate that produces a blue color, which turns yellow when stopped with a strong acid. [2] [9] Its absorbance is read at 450 nm. [2] For AP, pNPP (p-Nitrophenyl Phosphate) is a common substrate that produces a yellow product, measurable at 405 nm. [9]

- Other Types: Chemiluminescent substrates (which produce light) offer higher sensitivity than colorimetric ones, while fluorescent substrates enable detection with fluorometers. [17]

- Stop Solution: The enzyme-substrate reaction is typically terminated after 30-60 minutes using an acidic (e.g., H₂SO₄ or HCl) or basic (e.g., NaOH) solution. [2] This stabilizes the signal for measurement.

Table 3: Common Enzyme-Substrate Systems in ELISA

| Enzyme | Common Substrate | Signal Type | Product/Readout | Stop Solution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) | TMB (Tetramethylbenzidine) | Colorimetric | Blue → Yellow; read at 450 nm [2] | Acid (e.g., H₂SO₄, HCl) [2] |

| Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) | Hydrogen Peroxide + other chromogens | Colorimetric | Varies by chromogen | Acid [9] |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) | pNPP (p-Nitrophenyl Phosphate) | Colorimetric | Yellow; read at 405 nm [9] | Base (e.g., NaOH) [2] |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) | BCIP/NBT | Colorimetric | Blue precipitate [2] | Not Specified |

Experimental Protocols for ELISA Variants

The following protocols detail the setup of direct, indirect, and sandwich ELISAs, highlighting how the core components are utilized in each format.

Direct ELISA Protocol

The direct ELISA is the most straightforward format, using a single labeled antibody. [11]

- Coating: Dilute the antigen in a coating buffer (e.g., carbonate-bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.4) to a concentration of 2–10 µg/mL. Add 50–100 µL per well to a 96-well microplate and incubate for several hours to overnight at 4–37°C. [12] Wash the plate with PBS or a wash buffer to remove unbound antigen. [2]

- Blocking: Add a blocking buffer containing an irrelevant protein (e.g., 3–5% BSA in PBS) to all wells to cover any remaining protein-binding sites. Incubate for at least 1–2 hours at room temperature. Wash the plate. [9] [18]

- Detection with Conjugated Antibody: Add the enzyme-conjugated primary antibody specific to the antigen. Incubate for 1–2 hours at room temperature. Wash the plate thoroughly to remove any unbound antibody. [9]

- Signal Development and Reading: Add the appropriate enzyme substrate (e.g., TMB for HRP). Incubate in the dark for 15–30 minutes. Add the stop solution (e.g., 1M H₂SO₄ for TMB) and measure the absorbance immediately with a microplate reader. [9]

Indirect ELISA Protocol

The indirect ELISA introduces a secondary antibody for signal amplification, enhancing sensitivity. [16]

- Coating and Blocking: Perform the coating and blocking steps as described in the Direct ELISA protocol (Steps 1 and 2). [9]

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Add the unlabeled primary antibody specific to the antigen. Incubate for 1–2 hours at room temperature. Wash the plate. [9]

- Secondary Antibody Incubation: Add the enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody that is specific to the host species of the primary antibody (e.g., anti-rabbit IgG-HRP if the primary is from a rabbit). Incubate for 1–2 hours at room temperature. Wash the plate thoroughly. [9]

- Signal Development and Reading: Proceed with signal development and reading as in the Direct ELISA protocol (Step 4). [9]

Sandwich ELISA Protocol

The sandwich ELISA is the most sensitive and specific format, ideal for complex samples like serum or cell lysates. [11] [18] The protocol below is a detailed guide.

- Capture Antibody Coating: Dilute the capture antibody in a coating buffer to 1–10 µg/mL. Add 50–100 µL per well to a 96-well microplate. Cover the plate and incubate with gentle agitation for 2 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. Wash the plate three times with wash buffer. [18]

- Blocking: Block the plate with a protein-based blocking buffer (e.g., PBS with 3–5% BSA) for at least 1–2 hours at room temperature to prevent non-specific binding. Wash the plate. [9] [18]

- Antigen Incubation: Add the samples, standards, and controls to the wells. Incubate for 90 minutes at 37°C to allow the antigen to bind to the capture antibody. Wash the plate to remove unbound material. [9] [18]

- Detection Antibody Incubation: Add the detection antibody specific to a different epitope on the antigen. This antibody can be enzyme-conjugated (direct detection) or unlabeled (requiring a subsequent step with a conjugated secondary antibody for indirect detection). Incubate for 1–2 hours at room temperature and wash. [9] [18]

- Signal Development and Reading: If an indirect detection method was used, add the enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody at this stage, incubate, and wash. [9] Finally, add the substrate, incubate, stop the reaction, and read the absorbance. [18]

Sandwich ELISA Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

A successful ELISA relies on a suite of essential reagents and materials. The following table details key items and their functions for setting up a core ELISA laboratory.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for ELISA

| Item | Function / Description | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Microplate | 96-well or 384-well plate serving as the solid phase. | Clear polystyrene for colorimetry; black/white for fluorescence/chemiluminescence. [12] |

| Coating Buffer | Buffer for diluting antigen or capture antibody for plate adsorption. | Carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.4) or PBS (pH 7.4). [12] |

| Blocking Buffer | Solution of irrelevant protein to cover unused binding sites. | 1-5% BSA, ovalbumin, or casein in PBS to reduce background. [9] [18] |

| Wash Buffer | Buffer for removing unbound reagents between steps. | PBS or Tris buffer, often with a non-ionic detergent (e.g., Tween-20). [2] [9] |

| Antibody Pairs | Matched capture and detection antibodies for sandwich ELISA. | Must bind distinct, non-overlapping epitopes on the target antigen. [18] |

| Enzyme Conjugate | Antibody (or antigen) linked to the reporter enzyme. | HRP- or AP-conjugated primary or secondary antibodies. [2] [12] |

| Substrate | Chemical converted by the enzyme to a detectable signal. | TMB (HRP) or pNPP (AP) for colorimetric detection. [2] [9] |

| Stop Solution | Acidic or basic solution to halt the enzyme-substrate reaction. | 1-2 M H₂SO₄ or HCl; NaOH for some AP substrates. [2] |

| Microplate Reader | Instrument to measure the absorbance, fluorescence, or luminescence. | Spectrophotometer for colorimetric ELISA (read at 450nm for TMB). [2] |

Data Analysis and Best Practices

Accurate data analysis is critical for reliable quantification. Here are key pre- and post-assay considerations:

- Before Running the ELISA:

- Replicates: Run all standards and samples in duplicate or triplicate to assess pipetting error and calculate a coefficient of variation (CV). A CV of less than 20% is a best-practice target. [19]

- Standard Curve: Include a serial dilution of a known standard on every plate to account for inter-assay variability. [19]

- Controls: Use blank samples (buffer only) to subtract background absorbance and positive controls with known concentration to validate the assay. [19]

- Dilutions: Test samples at multiple dilutions to ensure at least one falls within the linear range of the standard curve. [19]

- After Running the ELISA:

- Standard Curve Fitting: Use a 4-parameter logistic (4-PL) curve fit for the standard dilution data, as this model typically provides the best fit for immunoassay data. [19]

- Background Subtraction: Subtract the average absorbance of the blank wells from all other readings. [19]

- Calculation: Use the standard curve to interpolate the concentration of unknown samples, remembering to multiply by any dilution factors applied. [19]

ELISA Data Analysis Steps

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) detects and quantifies biological molecules by exploiting the potent catalytic activity of enzymes to generate an amplified, measurable signal from antigen-antibody interactions. This detection principle transforms an invisible molecular binding event into a quantifiable colorimetric, chemiluminescent, or fluorescent output, providing researchers with a powerful tool for precise protein and antibody measurement. The core of this system relies on enzymes conjugated to detection antibodies that catalyze the conversion of substrates into detectable products, with the signal intensity directly proportional to the target analyte concentration [9] [2].

Core Enzyme-Substrate Systems in ELISA

The specificity and sensitivity of ELISA detection depend on carefully matched enzyme-substrate pairs. The most common systems utilize Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) or Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) due to their high turnover rates and stability when conjugated to antibodies [9] [2].

- Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) catalyzes the reduction of hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) while oxidizing a chromogenic substrate. Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) is a frequently used HRP substrate that produces a blue color during the reaction, which turns yellow when stopped with a strong acid like sulfuric or hydrochloric acid [9] [2]. The absorbance of this yellow solution is measured at 450 nm.

- Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) removes phosphate groups from its substrates. With para-Nitrophenylphosphate (pNPP) as a substrate, AP produces a yellow product, p-nitrophenol, which can be measured directly at 405-410 nm [9].

The remarkable signal amplification achieved stems from the enzyme's catalytic nature. A single enzyme molecule converts thousands of substrate molecules to product, greatly magnifying the signal from each antibody-antigen binding event [20]. For instance, carbonic anhydrase can turn over over 600,000 substrate molecules per second [20].

Detection Pathway Diagrams

The following diagrams illustrate the fundamental signaling pathways for the two primary enzyme systems used in ELISA.

Diagram Title: HRP-TMB Detection Pathway

Diagram Title: AP-pNPP Detection Pathway

Application Across ELISA Formats

The enzyme-substrate reaction is the universal detection endpoint across all major ELISA formats, though the methods for capturing the target and attaching the enzyme differ significantly. The following table compares how this detection principle is integrated into different assay architectures, each offering distinct advantages for specific applications [21] [9].

| ELISA Format | Assay Architecture | Integration of Enzyme-Substrate Detection | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct ELISA | Antigen is immobilized; detected by an enzyme-linked primary antibody. | Enzyme is directly conjugated to the primary antibody. Simplest workflow. | Minimal steps; avoids secondary antibody cross-reactivity. |

| Indirect ELISA | Antigen is immobilized; detected by an unlabeled primary antibody, then an enzyme-linked secondary antibody. | Enzyme is conjugated to a secondary antibody that binds the primary antibody. | Signal amplification through multiple secondary antibodies; highly sensitive; flexible. |

| Sandwich ELISA | Antigen is captured between a surface-bound antibody and a detection antibody. | Enzyme is typically linked via a secondary antibody that binds the detection antibody. | Highest specificity and sensitivity; suitable for complex samples. |

| Competitive ELISA | Sample antigen and labeled antigen compete for limited antibody binding sites. | Enzyme is conjugated to a reference antigen. Signal is inversely proportional to analyte concentration. | Ideal for detecting small molecules or inhibitors. |

Experimental Protocols and Performance Data

Recent research demonstrates the practical application of these detection principles, with sandwich ELISA being a preferred format for its high sensitivity and specificity. The following experimental protocols from current studies highlight the optimization of enzyme-substrate detection for specific targets.

Protocol 1: Sandwich ELISA for Pan-Merbecovirus Detection

A 2025 study established a sensitive sandwich ELISA for detecting the nucleocapsid (N) protein across multiple Merbecoviruses, including MERS-CoV and bat-derived viruses [22].

- Coating: Wells were pre-coated with a monoclonal capture antibody (1A8).

- Blocking: Blocked with a proprietary blocking buffer to prevent non-specific binding.

- Sample Incubation: Sample containing viral antigen was added and captured.

- Detection Antibody Binding: A biotinylated monoclonal detection antibody (10H6), recognizing a different epitope, was added.

- Enzyme Conjugate: Streptavidin conjugated to Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) was used.

- Substrate Reaction: The HRP substrate TMB was added, producing a blue color.

- Signal Stop & Measurement: The reaction was stopped with H₂SO₄, and absorbance was read at 450 nm.

Performance Data: The assay demonstrated high sensitivity with limits of detection (LOD) below 7.81 ng/mL for all tested merbecoviruses, and as low as 1.25 ng/mL for VsCoV-1. It also detected infectious virus at 1.3 × 10³ PFU/mL, showcasing the power of enzyme-mediated signal amplification for sensitive antigen detection [22].

Protocol 2: Sandwich ELISA for Dengue Virus Envelope Protein

A 2025 study developed a sandwich ELISA for the envelope domain III (EDIII) protein of dengue virus type 2 (DENV-2) [23].

- Coating: Wells were coated with a rabbit polyclonal anti-DENV-2_EDIII antibody.

- Blocking: Blocking was performed with 5% skimmed milk powder.

- Sample Incubation: Serial dilutions of the purified DENV-2_EDIII antigen standard or test samples were added.

- Detection Antibody Binding: The same rabbit polyclonal anti-DENV-2_EDIII antibody was used for detection.

- Enzyme Conjugate: An HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody was employed.

- Substrate Reaction: TMB substrate was added.

- Signal Stop & Measurement: The reaction was stopped with 2 M H₂SO₄, and absorbance was read at 450 nm.

Performance Data: This assay achieved an impressive LOD of 1.18 ng/mL and a quantitation range of 3.13–100 ng/mL, confirming that the ELISA format provides a wide dynamic range for accurate quantification [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for ELISA Detection

Successful implementation of ELISA relies on a set of critical reagents, each playing a vital role in the assay's performance and the fidelity of the final enzyme-substrate signal.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Detection |

|---|---|

| Microplate | Solid polystyrene surface for immobilizing capture antibodies or antigens [2]. |

| Coating Antibody | High-affinity antibody that binds and immobilizes the target antigen to the plate (e.g., mouse mAb 1A8) [22]. |

| Blocking Buffer | Protein-based solution (e.g., BSA, skim milk) that covers unused plastic surface to prevent non-specific binding of detection reagents [24] [25]. |

| Detection Antibody | Antibody that binds to a distinct epitope on the captured antigen; may be biotinylated (e.g., mouse mAb 10H6) or directly enzyme-conjugated [22] [23]. |

| Enzyme Conjugate | Critical signal-generating component. Often a Streptavidin-HRP complex (binds biotinylated detection Ab) or an enzyme-linked secondary antibody [22] [24]. |

| Chromogenic Substrate | Molecule (e.g., TMB, pNPP) enzymatically converted into a colored, measurable product [9] [2]. |

| Stop Solution | Strong acid (e.g., H₂SO₄) or base that halts the enzyme-substrate reaction, stabilizing the signal for measurement [2]. |

| Plate Reader | Spectrophotometer that measures the optical density (absorbance) of the colored product in each well, typically at 450 nm for TMB or 405 nm for pNPP [2]. |

The enzyme-substrate reaction remains the cornerstone of ELISA detection, providing the critical link between specific molecular recognition and quantifiable signal output. Ongoing refinements in enzyme conjugates, substrate chemistry, and assay automation continue to push the boundaries of sensitivity and precision, ensuring ELISA remains an indispensable tool for researchers and clinicians in the life sciences.

The Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) is a foundational biochemical technique that leverages the specificity of antigen-antibody interactions to detect and quantify soluble substances such as peptides, proteins, antibodies, and hormones [12] [26]. Since its original description by Engvall and Perlmann in 1971, ELISA has become a gold standard in research and diagnostic laboratories worldwide due to its high sensitivity, specificity, and versatility [12] [9]. The core principle involves immobilizing an antigen on a solid surface and complexing it with an antibody linked to a reporter enzyme; detection is achieved by measuring the enzyme's activity upon substrate introduction [12].

This guide provides an objective comparison of the three major ELISA formats—Direct, Indirect, and Sandwich ELISA. It is designed to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in their selection of the most appropriate assay format for specific applications, supported by experimental data, detailed protocols, and key reagent solutions.

Core Principles and Methodologies

The General ELISA Workflow

All ELISA types share a common sequence of core steps, which ensures the specific binding and detection of the target analyte. The workflow below illustrates these fundamental stages.

Step 1: Plate Coating. The antigen or capture antibody is passively adsorbed onto the surface of a polystyrene microplate well through hydrophobic interactions [12] [9]. Coating is typically performed using a carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.4) or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), with incubation times ranging from several hours at 37°C to overnight at 4°C [12] [27].

Step 2: Blocking. After coating, any remaining unsaturated binding sites on the plastic surface are saturated with an irrelevant protein or molecule, such as Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) or non-fat milk [12] [9]. This crucial step minimizes non-specific binding of detection antibodies in subsequent stages, thereby reducing background signal [28] [9]. Blocking is typically carried out for 1 to 2 hours at room temperature [27].

Step 3: Probing/Detection. The immobilized antigen is incubated with antigen-specific antibodies. The strategy for this step—whether using a labeled primary antibody or a matched set of unlabeled primary and labeled secondary antibodies—defines the type of ELISA and greatly influences its sensitivity and specificity [12] [29].

Step 4: Signal Measurement. A substrate specific to the reporter enzyme (e.g., HRP or AP) is added. The enzyme catalyzes a reaction that generates a measurable product, often a color change [2] [9]. The reaction is stopped with an acidic solution, and the optical density (OD) is measured with a microplate spectrophotometer, typically at 450 nm [30] [27]. The intensity of the signal is proportional to the amount of analyte in the sample.

Comparative Workflows for Direct, Indirect, and Sandwich ELISA

The following diagram details the specific procedural and reagent differences between the three main ELISA types.

Comparative Analysis of ELISA Types

Detection Strategies and Performance

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and disadvantages of each ELISA type to guide format selection.

Table 1: Comparison of Direct, Indirect, and Sandwich ELISA Methods

| Feature | Direct ELISA | Indirect ELISA | Sandwich ELISA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Antigen is immobilized; detected directly by a conjugated primary antibody [12] [29]. | Antigen is immobilized; detected by an unlabeled primary antibody, then a conjugated secondary antibody [12] [27]. | Antigen is captured by an immobilized antibody and detected by a second, specific antibody [12] [9]. |

| Key Steps | Coat antigen → Add conjugated primary Ab → Add substrate [9]. | Coat antigen → Add primary Ab → Add conjugated secondary Ab → Add substrate [9] [27]. | Coat capture Ab → Add antigen → Add detection Ab → (If needed: Add conjugated secondary Ab) → Add substrate [12] [9]. |

| Sensitivity | Lower, as there is no signal amplification [12] [29]. | High, due to signal amplification from multiple secondary antibodies binding to a single primary [12] [29]. | Highest, as the target antigen is bound by two specific antibodies, enhancing specificity and signal [12] [9]. |

| Specificity | High; reduced risk of cross-reactivity from secondary antibodies [12]. | Moderate; potential for cross-reactivity from the secondary antibody must be managed [12] [9]. | Very high; requires two distinct epitopes on the antigen to be bound, minimizing false positives [12] [26]. |

| Time Required | Faster (fewer steps) [12]. | Longer (extra incubation step) [12]. | Longest (multiple binding and incubation steps) [9]. |

| Cost & Flexibility | Higher cost and lower flexibility; each primary antibody must be individually conjugated [12]. | Lower cost and high flexibility; one conjugated secondary antibody can be used with many primary antibodies [12] [29]. | High cost; requires matched antibody pairs that recognize different epitopes on the same antigen [12] [9]. |

| Best For | Quick, initial screens; detecting immune responses in cells/tissues via immunohistochemistry [12]. | Antibody screening (e.g., serological tests), general protein detection, and when signal amplification is needed [2] [9]. | Quantifying complex samples with high precision (e.g., cytokines, hormones, biomarkers) [26] [9]. |

Quantitative Data Analysis and Interpretation

Accurate data analysis is critical for reliable quantification. The relationship between the measured Optical Density (OD) and analyte concentration differs by ELISA type.

- Standard Curve: Quantitative analysis requires a standard curve with known analyte concentrations, typically prepared via serial dilution [30]. The standard curve is plotted with concentration on the x-axis (log scale) and absorbance on the y-axis (linear scale) [2] [9].

- Signal-Concentration Relationship:

- In Sandwich and Indirect ELISA, the OD value is positively correlated with the analyte concentration [30]. More target analyte leads to more enzyme-conjugated antibody binding and a stronger signal.

- In Competitive ELISA (a variant not covered in detail here), the relationship is inverse; a higher sample analyte concentration results in a lower signal [12] [30].

- Curve Fitting: The standard curve is typically fitted using a 4-parameter logistic (4PL) or 5-parameter logistic (5PL) model, which accurately captures the sigmoidal nature of the assay's response across a wide dynamic range [30]. The coefficient of determination (R²) should be >0.98 to validate the curve fit [30]. Sample concentrations are then interpolated from this curve.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of an ELISA requires specific, high-quality reagents and equipment. The following table details the essential components for setting up an ELISA laboratory.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for ELISA

| Item | Function / Description | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Solid Phase | 96-well or 384-well polystyrene microplates that passively bind proteins [12] [2]. | Clear plates for colorimetry; white/black for fluorescence/chemiluminescence. Not tissue culture treated [12]. |

| Coating Buffer | Alkaline buffer for diluting antigen/antibody for plate coating to facilitate adsorption [12] [27]. | Carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.4) or PBS (pH 7.4) [12] [27]. |

| Blocking Buffer | A solution of irrelevant protein to cover any unsaturated binding sites on the plate to prevent non-specific binding [12] [9]. | 1-5% BSA, non-fat dry milk, or other animal proteins in PBS or Tris buffer [28] [9] [27]. |

| Capture & Detection Antibodies | High-affinity, specific antibodies are the backbone of any ELISA. For sandwich ELISA, a "matched pair" is required [12] [31]. | Must be validated for ELISA. Capture and detection antibodies should be from different host species to avoid interference [12]. |

| Enzyme Conjugates | Reporter enzymes linked to the primary or secondary antibody for signal generation [12] [2]. | Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) and Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) are most common [12] [9]. |

| Enzyme Substrate | The compound acted upon by the enzyme to produce a detectable signal [2] [9]. | TMB (turns blue with HRP, then yellow when stopped) and pNPP (turns yellow with AP) are common chromogenic substrates [2] [9]. |

| Wash Buffer | A buffered solution with a mild detergent used to remove unbound reagents between steps [2] [27]. | PBS or Tris buffer with 0.01-0.1% Tween-20 (PBST/TBST) [28] [27]. |

| Stop Solution | An acidic or basic solution to halt the enzyme-substrate reaction at a defined timepoint [2]. | 1M or 2M H₂SO₄ is commonly used for HRP/TMB reactions [2] [27]. |

| Microplate Reader | An instrument that measures the optical density (OD) in each well of the plate [2] [30]. | Spectrophotometer for colorimetric detection; can also be configured for fluorescent or luminescent readouts [30] [31]. |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Even well-optimized ELISAs can encounter problems. The table below outlines common issues and their solutions.

Table 3: Common ELISA Problems and Troubleshooting Strategies

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| High Background Signal | Incomplete plate washing [28].Inadequate blocking [28].Excessive detection antibody concentration [30] [28]. | Increase number of wash cycles; add a short incubation soak during washes [28].Increase blocking buffer concentration (e.g., 1% to 2% BSA) or extend blocking time [28].Titrate the detection antibody to find the optimal dilution [30]. |

| Low or No Signal | Expired or degraded substrate (e.g., TMB) [30].Inaccurate reagent preparation or missing a key reagent [30].Antigen concentration below assay detection limit. | Use fresh substrate and ensure it is stored correctly [30].Double-check protocol and pipetting. Ensure all reagents are added in the correct order [30].Concentrate the sample or use a more sensitive ELISA format (e.g., switch from direct to indirect) [29]. |

| High Variation Between Replicates | Inconsistent pipetting [30].Inhomogeneous samples or reagents [30].Plate edge effects (evaporation). | Calibrate pipettes and ensure proper pipetting technique [30].Vortex samples and centrifuge briefly before use to gather liquid [30].Use a plate seal during incubations and avoid using outer wells if necessary. |

The choice between Direct, Indirect, and Sandwich ELISA is a strategic decision that depends on the specific experimental goals and constraints.

- Direct ELISA offers simplicity and speed, making it suitable for quick antigen detection when a conjugated primary antibody is available and high sensitivity is not the primary concern [12] [29].

- Indirect ELISA provides enhanced sensitivity through signal amplification and greater flexibility, making it ideal for antibody screening applications and when the same secondary antibody can be used across multiple assays [12] [9].

- Sandwich ELISA delivers the highest specificity and sensitivity for antigen quantification, indispensable for measuring low-abundance proteins in complex biological mixtures like serum or cell culture supernatants, despite requiring more resources and optimization [12] [26] [9].

Understanding the principles, advantages, and limitations of each format empowers researchers to select the most appropriate tool for their needs, thereby ensuring robust, reliable, and meaningful experimental results in both basic research and drug development.

Methodology in Action: Step-by-Step Protocols and Applications

The Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) is a foundational technique in biomedical research and clinical diagnostics, enabling the detection and quantification of specific proteins, antibodies, hormones, and other biomolecules within complex mixtures [12]. Among its various formats, the direct ELISA represents the most straightforward approach, characterized by its simplified protocol and minimal procedural steps. In this assay, the antigen is immobilized directly onto a microplate well and detected using a single primary antibody that is conjugated directly to a reporter enzyme [12] [11]. This guide deconstructs the direct ELISA protocol, compares its performance against other common ELISA variants, and provides the visual tools necessary for effective experimental planning and execution.

Visualizing the Direct ELISA Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental steps and molecular interactions in a direct ELISA.

Detailed Step-by-Step Direct ELISA Protocol

Plate Coating: Antigen Immobilization

Procedure: Dilute the purified antigen in a coating buffer. Carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6) or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) are commonly used [12] [32]. Add 50-100 µL of the antigen solution to each well of a 96-well polystyrene microplate [27]. Cover the plate with adhesive plastic to prevent evaporation and incubate for 1 hour at 37°C or overnight at 4°C [32]. The optimal antigen concentration for coating should be determined experimentally but is generally below 20 µg/mL to avoid high background [27].

Mechanism: This step relies on passive adsorption, where hydrophobic interactions between non-polar protein residues and the plastic surface result in irreversible immobilization of the antigen [12].

Blocking: Minimizing Non-Specific Binding

Procedure: Remove the coating solution by flicking the plate over a sink. Add 200-300 µL of blocking buffer per well. Common blocking agents include 1-5% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), non-fat dry milk, or animal sera in PBS [27] [9]. Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature. Wash the plate once with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (wash buffer) [32].

Mechanism: Blocking agents saturate any remaining protein-binding sites on the polystyrene surface that were not occupied during the coating step, thereby preventing non-specific binding of detection antibodies in subsequent steps and reducing background signal [9].

Detection: Antibody Binding

Procedure: Prepare the enzyme-conjugated primary antibody in blocking buffer at the manufacturer's recommended dilution (typically 1-10 µg/mL) [12]. Add 100 µL of the antibody solution to each well. Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature with gentle shaking. Remove the antibody solution and wash the plate 3-5 times with wash buffer (300 µL per well) to remove unbound antibodies [27] [32].

Mechanism: The conjugated primary antibody specifically binds to epitopes on the immobilized antigen. Common enzyme labels include Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) and Alkaline Phosphatase (AP), which will later catalyze the conversion of substrates into detectable products [12].

Signal Development and Detection

Procedure: Add 100 µL of substrate solution to each well. For HRP-conjugated antibodies, use TMB (3,3',5,5'-tetramethylbenzidine), which produces a blue color, or ABTS (2,2'-azino-di-[3-ethyl-benzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid] diammonium salt), which produces a green color. For AP-conjugated antibodies, PNPP (p-Nitrophenyl Phosphate) is commonly used, yielding a yellow product [33] [34]. Incubate for 15-30 minutes at room temperature, protected from light. Stop the reaction when sufficient color develops (for TMB, add an equal volume of stop solution, typically 0.16 M sulfuric acid, which changes the color to yellow) [32]. Measure the absorbance immediately using a microplate reader at the appropriate wavelength (450 nm for acid-stopped TMB, 405 nm for PNPP) [33].

Mechanism: The enzyme conjugated to the detection antibody catalyzes the conversion of the substrate into a colored, fluorescent, or chemiluminescent product. The intensity of the signal is directly proportional to the amount of antigen present in the well [12].

Comparative Analysis of ELISA Formats

Performance Characteristics of ELISA Types

Table 1: Comparative analysis of direct, indirect, sandwich, and competitive ELISA formats

| Parameter | Direct ELISA | Indirect ELISA | Sandwich ELISA | Competitive ELISA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Low to moderate [12] [11] | High (signal amplification) [12] [9] | Highest (typically 2-5x more sensitive than direct/indirect) [33] [11] | Moderate [11] |

| Time Required | ~3-4 hours (fastest protocol) [12] | ~4-5 hours (additional incubation step) [12] | ~5-6 hours (longest protocol) [11] | ~4-5 hours [11] |

| Complexity | Low (fewest steps) [12] | Moderate [12] | High (requires antibody pairing) [12] [11] | Moderate [11] |

| Specificity | Lower (single antibody) [11] | Moderate (potential for secondary cross-reactivity) [12] [9] | Highest (two antibodies required) [12] [11] | Lower (single antibody) [11] |

| Cost | Higher (labeled primary antibodies needed) [9] | Lower (versatile secondary antibodies) [12] [9] | Highest (two specific antibodies) [12] | Moderate [11] |

| Signal Amplification | No amplification (minimal signal) [12] | Yes (multiple secondary antibodies per primary) [12] | Yes (can be combined with indirect detection) [12] | No amplification [11] |

| Antigen Requirements | Must be adsorbable to plate [12] | Must be adsorbable to plate [12] | Must have at least two epitopes [33] | Suitable for small antigens [12] [11] |

| Typical Applications | Antibody affinity/specificity testing [11] | Measuring endogenous antibodies [11] | Quantifying biomarkers in complex samples [11] | Measuring small molecules/hormones [12] [11] |

Visual Comparison of ELISA Methodologies

The following diagram illustrates the key structural and procedural differences between the four main ELISA formats.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key research reagent solutions for direct ELISA

| Reagent/Material | Function | Typical Composition/Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Microplate | Solid phase for immobilization | 96-well polystyrene plates (clear for colorimetric detection) [12] |

| Coating Buffer | Facilitates antigen adsorption | 50 mM carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6) or PBS (pH 7.4) [27] [32] |

| Blocking Buffer | Prevents non-specific binding | 1-5% BSA, non-fat dry milk, or animal serum in PBS [27] [9] |

| Wash Buffer | Removes unbound reagents | PBS or Tris-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween 20 detergent [32] [35] |

| Enzyme-Conjugated Primary Antibody | Specific detection | HRP or AP conjugated to antigen-specific antibody [12] |

| Enzyme Substrate | Generates detectable signal | TMB, ABTS (for HRP); PNPP (for AP) [33] [34] |

| Stop Solution | Terminates enzyme reaction | 0.16-2 M sulfuric acid (for TMB); 2 N NaOH (for PNPP) [33] [32] |

Applications and Strategic Implementation

When to Choose Direct ELISA

The direct ELISA format offers distinct advantages in specific research scenarios. Its streamlined protocol makes it ideal for high-throughput screening applications where speed is prioritized over maximal sensitivity [12]. The method is particularly valuable for assessing antibody affinity and specificity, as it eliminates potential cross-reactivity from secondary antibodies [11]. Additionally, direct detection is commonly employed in immunohistochemical staining of tissues and cells, where the direct labeling approach provides precise localization [12].

Limitations and Considerations

Researchers should recognize the inherent limitations of direct ELISA. The technique generally exhibits lower sensitivity compared to indirect or sandwich formats due to the absence of signal amplification [12]. The requirement for individually conjugated primary antibodies makes assay development time-consuming and expensive [12]. Additionally, the labeling process of primary antibodies with reporter enzymes may potentially affect their immunoreactivity, compromising binding affinity in some cases [12].

The direct ELISA remains an essential technique in the molecular biologist's arsenal, particularly when experimental priorities include protocol simplicity, rapid results, and elimination of secondary antibody cross-reactivity. While it may not offer the sensitivity of sandwich ELISA or the versatility of indirect ELISA, its straightforward approach makes it invaluable for specific applications including initial antibody characterization and high-throughput screening. Understanding the fundamental workflow, as visualized in this guide, along with its performance characteristics relative to other immunoassay formats, enables researchers to make informed methodological selections based on their specific experimental requirements, sample availability, and detection sensitivity needs.

The Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) remains a cornerstone technique in immunology and molecular biology for detecting and quantifying specific proteins or antigens [27] [12]. Since its initial description in 1971, it has evolved into a safer, more convenient alternative to radioimmunoassay and has become indispensable for both research and clinical diagnostics [36]. Among its various formats, the indirect ELISA is particularly renowned for its superior sensitivity and flexibility, making it a preferred choice for applications like quantifying antibody responses in serological studies and vaccine trials [37] [11].

This guide provides an objective comparison of the indirect ELISA against other common variants—direct, sandwich, and competitive ELISA—framed within a broader thesis on ELISA technology. We will delve into the detailed protocol, explore advanced signal amplification strategies, and summarize key performance data to help researchers and drug development professionals select the optimal assay for their specific needs.

Core Principles: Indirect vs. Other ELISA Formats

The fundamental principle of any ELISA is the immobilization of an antigen on a solid surface (typically a microplate) and its detection via antibodies linked to a reporter enzyme, which generates a measurable signal [27] [12]. The formats differ primarily in their approach to capture and detection.

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of the four main ELISA types:

| ELISA Type | Core Principle | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages | Ideal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct ELISA [38] [11] | A labeled primary antibody binds directly to the immobilized antigen. | - Quick and simple protocol [12] [39].- Fewer steps, lower risk of cross-reactivity [29] [12]. | - Less sensitive (no signal amplification) [12] [36].- Requires conjugated primary antibodies [12]. | - Assessing antibody affinity [11].- Rapid antigen screening [38]. |

| Indirect ELISA [38] [11] | An unlabeled primary antibody binds the antigen; a labeled secondary antibody then binds the primary. | - High sensitivity (signal amplification) [29] [12].- Flexible (same secondary can detect many primaries) [12] [11].- Maximum immunoreactivity of primary antibody [12]. | - More complex, longer protocol [39].- Potential for secondary antibody cross-reactivity [12] [11]. | - Measuring endogenous antibodies (e.g., serology) [36] [11].- Antibody titration in vaccine studies [38]. |

| Sandwich ELISA [38] [11] | Two antibodies specific to different epitopes "sandwich" the antigen. The detection can be direct or indirect. | - Highest specificity and sensitivity [12] [11].- Compatible with complex samples (e.g., serum) [11]. | - Requires a matched pair of antibodies [38].- Technically demanding and costly to develop [38]. | - Quantifying specific antigens in complex samples [38].- Biomarker detection in disease diagnostics [38]. |

| Competitive/Inhibition ELISA [12] [38] | Sample antigen and a labeled reference antigen compete for a limited number of antibody binding sites. | - Useful for quantifying small molecules [38] [11].- Flexible, can be adapted from other formats [38]. | - Less sensitive than sandwich ELISA [38].- Requires careful optimization [38]. | - Detecting small molecules (drugs, hormones) [38] [36].- Screening for contaminants [38]. |

Visualizing the Indirect ELISA Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the key steps and reagent interactions in a typical indirect ELISA procedure.

Detailed Indirect ELISA Protocol and Reagent Solutions

The following protocol is adapted from optimized methodologies used in recent research, such as for quantifying virus-specific antibodies [37].

Sample Preparation

Samples like serum, plasma, or cell culture supernatants must be properly prepared. For serum/plasma, collect blood in an appropriate anti-coagulant (e.g., EDTA), centrifuge at 1,000–10,000 x g for 10 minutes at 4°C, and carefully collect the supernatant [27]. Aliquot to minimize freeze-thaw cycles and store at -80°C [27]. Before the assay, heat-inactivate serum or plasma at 56°C for 30 minutes to denature complement proteins, then centrifuge at 1,000 x g for 10 minutes to remove precipitates [37].

Step-by-Step Protocol

- Plate Coating: Dilute the purified antigen in a carbonate-bicarbonate coating buffer (pH ~9.4) to a concentration generally below 20 µg/mL to avoid high background [27]. Add 100 µL per well to a medium-binding 96-well microplate. Cover the plate and incubate with gentle agitation for 2 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C [27] [37].

- Washing: Flick the plate to remove the coating solution. Wash each well three times with a wash buffer, such as PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 (PBST). If washing manually, firmly tap the plate upside down on absorbent paper after each wash to remove residual liquid [27] [37].

- Blocking: Add 200 µL of a blocking buffer to each well to cover all unsaturated binding sites. Common blockers include 1% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) in PBST or commercially available casein blockers [27] [37]. Incubate with gentle agitation for 1–2 hours at room temperature.

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Dilute the primary antibody (e.g., patient serum) in a suitable diluent like BSA or goat serum assay buffer [37]. Add 100 µL of the diluted sample or standard to the wells. Cover the plate and incubate for 2 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C [27].

- Washing: Wash the plate as in step 2, repeating the process three times to remove unbound primary antibody.

- Secondary Antibody Incubation: Dilute an enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody (e.g., Goat anti-human IgG-HRP) in blocking buffer. Add 100 µL per well, cover the plate, and incubate for 2 hours at room temperature [27] [37].

- Washing: Perform a final wash step, again repeating three times to ensure all unbound secondary antibody is removed.

- Signal Detection: Add 100 µL of an appropriate substrate to each well. For Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP), Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) is a common substrate. Incubate for 10-30 minutes at room temperature in the dark [37].

- Stop and Read: Stop the enzymatic reaction by adding 50-100 µL of a stop solution (e.g., 1M H₂SO₄ or a commercial TMB stop solution) [37]. Measure the absorbance immediately using a plate reader at the appropriate wavelength (e.g., 450 nm for TMB).

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents

This table details the key reagents required for a successful indirect ELISA.

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Role | Example / Composition |

|---|---|---|

| Coating Buffer | Provides optimal pH and ionic conditions for antigen adsorption to the plate. | Carbonate-Bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.4) [27] |

| Wash Buffer | Removes unbound reagents and reduces non-specific background signal. | PBS (Phosphate Buffered Saline) + 0.05% Tween-20 (PBST) [37] |

| Blocking Buffer | Covers any remaining protein-binding sites on the plate to prevent non-specific antibody binding. | 1% BSA in PBST, 5% Goat Serum, or Commercial Casein Buffer [27] [37] |

| Primary Antibody | Binds specifically to the target antigen of interest. | Patient serum, monoclonal antibody, or polyclonal antiserum [36] |

| Enzyme-Linked Secondary Antibody | Binds to the primary antibody and produces a measurable signal. Must be specific to the host species of the primary antibody. | Goat anti-human IgG-HRP, Donkey anti-rabbit IgG-AP [27] [37] |

| Enzyme Substrate | Reacts with the enzyme on the secondary antibody to generate a detectable (e.g., colorimetric) product. | TMB (for HRP), pNPP (for Alkaline Phosphatase) [37] |

Advanced Considerations: Signal Amplification and Optimization

Signal Amplification Strategies

The inherent signal amplification in indirect ELISA comes from multiple secondary antibodies binding to a single primary antibody [12]. For detecting low-abundance targets, this can be further enhanced using biotin-streptavidin chemistry [36].

In this advanced format, a biotin-conjugated primary or secondary detection antibody is used. This is followed by the addition of streptavidin conjugated to HRP (SA-HRP) or a poly-HRP-40 conjugate, which can bind multiple biotin molecules, dramatically increasing the number of enzyme molecules per antibody-antigen complex and thus the assay's sensitivity [37]. The diagram below illustrates this powerful amplification system.

Key Optimization Parameters

- Antibody Titration: The optimal dilution for both primary and secondary antibodies must be determined empirically through checkerboard titration to maximize the signal-to-noise ratio [27] [12].

- Specificity and Cross-Reactivity: A major consideration in indirect ELISA is ensuring the secondary antibody is specific only to the primary antibody and does not cross-react with the capture antigen or other components [12] [36]. Using cross-adsorbed secondary antibodies and appropriate blocking buffers is critical [12].

- Sample Matrix Effects: Complex sample matrices like serum can interfere with antibody binding. Using a sample diluent that matches the matrix of the standard curve (e.g., containing a percentage of the relevant serum) can improve accuracy.

Comparative Performance Data and Future Trends

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes objective performance metrics across ELISA formats, illustrating the trade-offs between different methods.

| Performance Metric | Direct ELISA | Indirect ELISA | Sandwich ELISA | Competitive ELISA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assay Time | ~3-4 hours (Fastest) [11] | ~4-6 hours (Moderate) [39] | ~5-8 hours (Longest) [39] | ~4-6 hours (Moderate) |

| Sensitivity | Low (No amplification) [29] [36] | High (Amplification via secondary Ab) [29] [12] | Very High (Amplification & two antibodies) [11] | Moderate (Limited by competition) [38] |

| Specificity | Moderate (Single antibody) [11] | Moderate (Depends on secondary) [11] | Very High (Two distinct antibodies) [12] [11] | Moderate (Single antibody) [11] |

| Flexibility | Low (Each primary must be conjugated) [12] | High (Same secondary for many primaries) [12] [11] | Low (Requires matched pair) [38] | Moderate [38] |

| Cost & Complexity | Low (Fewer steps/reagents) | Low to Moderate | High (Two specific antibodies) [38] | Moderate to High |

The Future: Next-Generation ELISA

The ELISA market is evolving, with a significant shift toward "Next-Generation ELISA" or ELISA 2.0 platforms [40]. Key trends include:

- Multiplexing: Technologies like Luminex and Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) enable the simultaneous quantification of multiple analytes from a single sample, revolutionizing biomarker profiling [40] [38].

- Advanced Detection Methods: The replacement of traditional colorimetric substrates with chemiluminescent, electrochemical, and fluorescent reporters offers superior quantification and sensitivity, crucial for detecting low-abundance biomarkers in early disease diagnosis [40].

- Digital ELISA and Automation: Digital ELISA platforms push sensitivity to the single-molecule level, while integrated automation and microfluidic "lab-on-a-chip" devices enhance throughput, reproducibility, and reduce costs [40].

The indirect ELISA remains a powerful and versatile tool in the scientific arsenal, striking an excellent balance between sensitivity, flexibility, and practicality. Its core strength lies in its signal amplification mechanism, making it ideally suited for quantifying antibody levels in serology, immunology research, and vaccine development.

The choice of ELISA format, however, is fundamentally dictated by the experimental question and available reagents. For maximum specificity and sensitivity for an antigen, a sandwich ELISA is superior. For small molecules, a competitive format is necessary. For straightforward antigen detection where sensitivity is not paramount, a direct ELISA may suffice.

As immunoassay technology advances, the principles of the indirect ELISA continue to be refined and integrated into more powerful, multiplexed, and automated systems, ensuring its continued relevance in both basic research and clinical diagnostics.