ELISA Protocol Optimization: A Comprehensive Guide to Enhance Assay Performance for Researchers

This article provides a systematic guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to optimize Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) protocols.

ELISA Protocol Optimization: A Comprehensive Guide to Enhance Assay Performance for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a systematic guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to optimize Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) protocols. Covering foundational principles, advanced methodological applications, step-by-step troubleshooting, and rigorous validation techniques, it synthesizes current best practices to address common challenges such as cross-reactivity, high background, and poor reproducibility. The content aims to empower users to achieve highly sensitive, specific, and reliable quantitation of proteins, hormones, and antibodies in diverse biological matrices, ultimately improving data quality and efficiency in both research and diagnostic settings.

Mastering ELISA Fundamentals: Principles, History, and Core Components

The Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) represents a cornerstone technology in biomedical research and clinical diagnostics, having evolved from a novel immunoassay into an indispensable tool for protein quantification. First introduced in 1971 by Engvall and Perlmann as a safer alternative to radioimmunoassays, ELISA revolutionized biological detection by replacing radioactive labels with enzymes that produce measurable color changes upon substrate reaction [1] [2]. This transformation established a new paradigm for immunoassays that combined exceptional sensitivity with practical safety. The technique's enduring relevance stems from its powerful antibody-based design that delivers high specificity, sensitivity, and adaptability across diverse applications from virology to drug discovery [2] [3]. Within the context of ELISA protocol optimization research, understanding this evolutionary trajectory provides critical insights into how methodological refinements have expanded the technique's capabilities while maintaining its fundamental principles. This application note traces key historical developments, details optimized protocols, and explores emerging applications that continue to solidify ELISA's role in modern scientific workflows.

Historical Milestones and Technological Evolution

The development of ELISA represents a series of strategic innovations building upon foundational immunoassay principles. The historical trajectory reveals a consistent pattern of problem-solving that addressed limitations in safety, sensitivity, and practicality.

Key Historical Developments

Table 1: Major Historical Milestones in ELISA Development

| Year | Development | Key Innovators/Context | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1941 | Immunofluorescence | Albert H. Coons and team | Pioneered antibody labeling with fluorescent dyes for antigen visualization in tissues [1]. |

| 1960 | Radioimmunoassay (RIA) | Rosalyn Sussman Yalow and Solomon Berson | Enabled detection of minute biological substances using radioactive isotopes; posed health risks [1]. |

| 1971 | Invention of ELISA | Eva Engvall and Peter Perlmann (independently) | Introduced enzyme-based detection as safer alternative to RIA [1] [2] [3]. |

| 1976 | Competitive ELISA | Developed for human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) detection | Allowed measurement of small molecules and hormones with high precision [1]. |

| 1977 | Sandwich ELISA | Introduced for enhanced specificity | Used capture and detection antibodies to "sandwich" antigen; ideal for complex samples [1]. |

| 1978 | Indirect ELISA | Created for human serum albumin detection | Employed secondary antibodies for signal amplification; increased sensitivity [1]. |

| 1985 | HIV Screening | First widely used HIV screening test | Critical public health milestone for controlling HIV/AIDS spread [1] [3]. |

| 1990s | Automation & Multiplexing | Introduction of robotic systems | Enabled high-throughput screening; minimized human error [1]. |

| 2000s | CLIA, ELFA, Microfluidics | Chemiluminescence and fluorescent assays | Provided higher sensitivity and portable point-of-care devices [1]. |

| 2010s | Digital ELISA, Integration | Single-molecule detection | Combined with mass spectrometry and NGS for detailed analyses [1]. |

| 2020s | Point-of-Care, COVID-19 | Pandemic-driven innovations | Rapid SARS-CoV-2 antibody detection; AI integration for data analysis [1]. |

Technological Transitions

The evolution from immunofluorescence to RIA and finally to ELISA marked a deliberate shift toward safer, more practical detection methodologies. While immunofluorescence established the principle of labeled antibodies, and RIA demonstrated exceptional sensitivity for hormone detection, the radiation hazards associated with RIA created a pressing need for alternatives [1]. The critical innovation emerged when researchers discovered that enzymes could effectively replace radioactive isotopes when chemically bound to antibodies, producing detectable signals through colorimetric, chemiluminescent, or fluorescent outputs [4].

The 1990s witnessed a transformative phase with the integration of automation and multiplexing capabilities. Automated ELISA systems featuring robot-assisted liquid handling and microplate readers significantly increased throughput while minimizing inter-assay variability [1]. Concurrently, multiplex ELISA techniques enabled simultaneous detection of multiple analytes within a single sample, dramatically enhancing data density from precious biological specimens [1]. These advancements established the technical foundation for contemporary high-throughput screening applications in drug discovery and clinical diagnostics.

Fundamental ELISA Principles and Formats

ELISA operates on the principle of detecting antigen-antibody interactions through enzyme-mediated signal amplification. The core components include a solid phase (typically 96-well microplates), capture molecules (antibodies or antigens), enzyme-labeled conjugates, and substrates that generate detectable signals [4]. The critical innovation lies in the "sorbent" nature of the assay, where antigens or antibodies adhere to plastic surfaces, and the "enzyme-linked" detection system that produces measurable outputs [4].

Comparative ELISA Formats

Table 2: Key Characteristics of Major ELISA Formats

| Format | Principle | Sensitivity | Applications | Advantages/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct ELISA | Antigen immobilized directly; single enzyme-labeled primary antibody detects target [3]. | Moderate | Antigen detection, screening [5] [6]. | Advantages: Simple, rapid, minimal cross-reactivity [6].Limitations: Lower sensitivity, primary antibody must be labeled. |

| Indirect ELISA | Antigen coated; primary antibody binds, enzyme-linked secondary antibody detects primary [4] [3]. | High | Antibody detection, serology [1] [4]. | Advantages: Signal amplification, flexible, same secondary for multiple primaries [1].Limitations: Potential cross-reactivity. |

| Sandwich ELISA | Capture antibody immobilized; antigen sandwiched between capture and detection antibodies [1] [7]. | Highest | Quantifying proteins, cytokines in complex samples [1] [5]. | Advantages: High specificity/sensitivity, no sample purification [1] [6].Limitations: Requires two epitope-specific antibodies. |

| Competitive ELISA | Sample antigen competes with labeled antigen for limited antibody binding sites [1] [3]. | High for small molecules | Hormones, small molecules, haptens [1] [5]. | Advantages: Suitable for small antigens, consistent [1] [6].Limitations: Inverse signal relationship. |

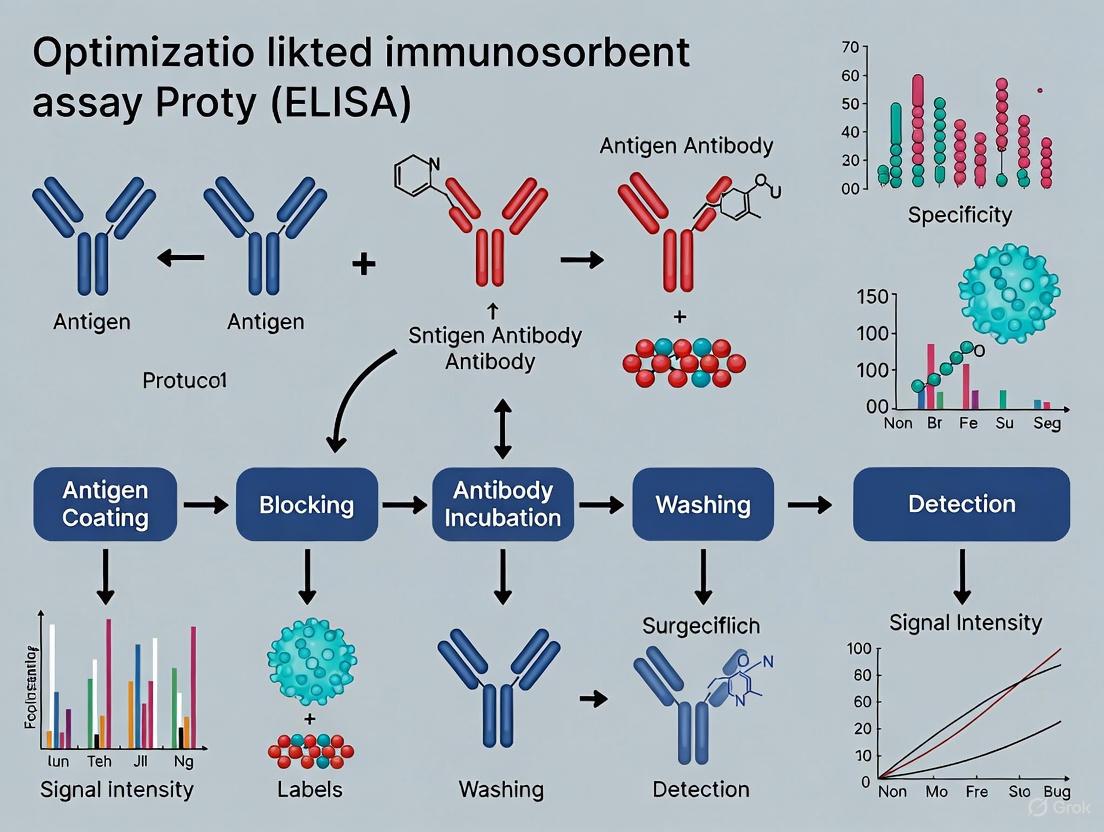

Figure 1: Workflow comparison of major ELISA formats showing key procedural differences and signal generation mechanisms.

Modern Applications and Workflow Integration

Contemporary Application Domains

ELISA maintains critical importance across diverse scientific and diagnostic domains. In infectious disease surveillance, ELISA-based tests revolutionized HIV screening beginning in 1985 and continue to serve as frontline diagnostic tools for diseases including malaria, dengue fever, and influenza [1] [3]. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted ELISA's adaptability, with extensive application for detecting antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, supporting epidemiological studies and vaccine efficacy evaluations [1].

In drug discovery and development, ELISAs provide robust quantification of drug concentrations in biological samples, enabling crucial pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies [3]. The technique's precision supports biomarker validation in preclinical studies, particularly in fields requiring detection of subtle protein changes in complex fluids [2]. Additionally, ELISA formats remain integral to vaccine development through measurement of antibody responses, assessment of immunogenicity, and optimization of vaccine formulations [3].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ELISA Optimization

| Component | Function | Examples & Specifications | Optimization Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solid Phase | Matrix for analyte immobilization | 96-well microplates (polystyrene, polyvinyl) [4] | Plate binding capacity; well-to-well consistency; compatibility with detection system. |

| Capture Molecule | Binds target analyte | Coating antibodies (1-15 µg/mL depending on purity) [7] | Affinity-purified antibodies recommended for optimal signal-to-noise [7]. |

| Blocking Buffer | Prevents non-specific binding | BSA, non-fat milk, or commercial blocking solutions [5] | Concentration optimization critical; test different solutions for minimal background. |

| Detection Antibody | Binds captured analyte | Enzyme-conjugated detection antibody (0.5-10 µg/mL) [7] | Specificity for non-overlapping epitope (sandwich ELISA); concentration titration needed. |

| Enzyme Conjugate | Signal generation | HRP (20-200 ng/mL) or AP (100-200 ng/mL) conjugates [7] | Concentration depends on detection system (colorimetric, chemiluminescent, fluorescent). |

| Substrate | Enzyme substrate conversion | TMB (colorimetric), Luminol (chemiluminescent) [4] [3] | Selection based on sensitivity requirements and available detection instrumentation. |

| Wash Buffer | Remove unbound components | PBS with Tween-20 or commercial wash buffers [4] | Sufficient washes between steps; avoid over-washing that may disrupt bound complexes. |

| Stop Solution | Halts enzyme reaction | Acidic (H₂SO₄, HCl) or basic (NaOH) solutions [4] | Compatible with substrate and reading wavelength; adds reproducibility to timing. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Optimized Sandwich ELISA Protocol

The sandwich ELISA format provides exceptional specificity and sensitivity, making it ideal for quantifying proteins in complex biological samples [1] [6]. The following optimized protocol incorporates critical steps for robust assay performance.

Protocol Workflow

Figure 2: Detailed workflow for optimized sandwich ELISA protocol highlighting critical parameters and incubation conditions.

Stepwise Procedure

Plate Coating: Dilute capture antibody in coating buffer to optimal concentration (1-12 µg/mL for affinity-purified antibodies) [7]. Dispense 100 µL/well into 96-well microplate. Seal plate and incubate overnight at 4°C for maximum binding efficiency.

Washing: Aspirate coating solution and wash plate three times with 300 µL/well of wash buffer (typically PBS with 0.05% Tween-20). Soak wells for 1-2 minutes during each wash cycle to ensure thorough removal of unbound components [5]. After final wash, invert plate and blot against clean paper towels to remove residual liquid.

Blocking: Add 200-300 µL/well of blocking solution (e.g., 1-5% BSA or commercial blocking buffer). Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature with gentle shaking [8]. Blocking is critical for minimizing non-specific binding and reducing background signal.

Sample and Standard Incubation: Prepare serial dilutions of protein standard in diluent that matches sample matrix. Add 100 µL/well of standards, samples, and appropriate controls (blank, positive control). Incubate 2 hours at room temperature with gentle shaking. Include replicate wells for statistical reliability [9].

Detection Antibody Incubation: Dilute biotinylated or enzyme-conjugated detection antibody in standard diluent (optimal concentration typically 0.5-5 µg/mL for affinity-purified antibodies) [7]. After sample incubation and washing, add 100 µL detection antibody/well. Incubate 2 hours at room temperature.

Enzyme Conjugate Incubation: For biotinylated detection antibodies, prepare streptavidin-HRP conjugate dilution in standard diluent (20-200 ng/mL for colorimetric detection) [7]. Add 100 µL/well and incubate 30-60 minutes at room temperature protected from light.

Signal Development: Prepare fresh substrate solution according to manufacturer instructions. Add 100 µL substrate/well and incubate for precisely 15-30 minutes in the dark. Monitor color development for optimal signal intensity within the linear range.

Reaction Termination and Reading: Add 50-100 µL stop solution (typically 0.16M H₂SO₄ for TMB substrate) to each well. Read absorbance at 450 nm with 570 nm or 630 nm reference wavelength within 30 minutes to ensure signal stability [4] [5].

Competitive ELISA Protocol

For small molecules and haptens with single epitope sites, competitive ELISA provides superior quantification [1] [6]. The protocol modifies key steps from the sandwich approach:

Plate Coating: Coat plates with known antigen concentration (2-10 µg/mL) overnight at 4°C [6].

Competition Incubation: Mix constant amount of enzyme-labeled antibody with serial dilutions of standard or sample. Simultaneously add mixture to antigen-coated wells. Alternatively, pre-incubate sample with limited antibody before adding to antigen-coated wells.

Detection: Following competition incubation and washing, proceed directly to substrate addition (skip detection antibody step). The signal intensity is inversely proportional to analyte concentration in the sample [5].

Data Analysis: Generate standard curve with highest concentration corresponding to lowest OD value [9].

ELISA Optimization and Validation Strategies

Systematic Optimization Approaches

ELISA development requires meticulous optimization of each component to maximize assay window (difference between full signal and background) [8]. The checkerboard titration method represents the most efficient approach for simultaneous optimization of multiple parameters.

Figure 3: ELISA optimization strategy using checkerboard titration to simultaneously evaluate multiple parameters for optimal assay performance.

Critical Validation Procedures

Assay validation ensures ELISA results accurately reflect biological reality. Three essential validation approaches include:

Spike and Recovery: Assess matrix effects by adding known analyte amounts to both sample matrix and standard diluent. Compare quantified values after ELISA completion. Ideal recovery ranges between 80-120%; significant deviations indicate matrix interference requiring diluent modification [8] [9].

Dilutional Linearity: Serially dilute high-concentration sample beyond the standard curve's lower limit. Calculate observed versus expected concentrations after accounting for dilution factors. Proper linearity (%CV <15%) confirms consistent antibody affinity across analyte concentrations [8] [5].

Parallelism: Evaluate potential differences in antibody binding affinity between endogenous analyte and standard curve analyte. Serially dilute samples with naturally high analyte concentration and analyze against standard curve. Acceptable parallelism demonstrates consistent %CV across dilutions, validating standard curve applicability to biological samples [8].

Data Analysis and Quality Control

Standard Curve Generation and Analysis

Quantitative ELISA relies on accurate standard curve generation using serial dilutions of known analyte concentrations. Key considerations include:

- Dilution Scheme: Prepare 2-fold, 3-fold, or 5-fold serial dilutions covering the expected sample concentration range. Include at least 6-8 standard points plus blank [5].

- Replicate Measurements: Run standards and samples in duplicate or triplicate to assess precision and identify pipetting errors [9].

- Curve Fitting Models: The 4-parameter logistic (4PL) model typically provides optimal fit for sigmoidal ELISA standard curves:

- Quality Metrics: Standard curves should demonstrate R² > 0.98 for reliable quantification. Samples with OD values outside the standard curve range require dilution or concentration [5].

Troubleshooting Common ELISA Issues

Table 4: ELISA Troubleshooting Guide for Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low OD/No Signal | Expired substrate; inadequate incubation; over-washing; low antibody concentration [5]. | Use fresh substrate; validate incubation conditions; optimize wash stringency; titrate antibodies [5]. | Implement reagent QC; establish optimized protocol; use timer for incubations. |

| High Background | Incomplete washing; excessive detection antibody; inadequate blocking; non-specific binding [5]. | Increase wash cycles/volume; dilute detection antibody; optimize blocking solution; include negative controls [5]. | Test multiple blocking buffers; optimize antibody concentrations; validate wash efficiency. |

| High Variation Between Replicates | Inconsistent pipetting; plate sealing issues; temperature gradients; sample precipitation [9]. | Calibrate pipettes; ensure proper seal; use stable incubation environment; mix samples thoroughly [9]. | Train on pipetting technique; use quality seals; pre-warm reagents; mix samples before addition. |

| Poor Standard Curve Fit | Improper standard dilution; inadequate curve range; uneven coating; enzyme instability [5]. | Verify dilution calculations; expand standard range; ensure consistent coating; use fresh conjugates [5]. | Prepare fresh standard dilutions; include points at curve extremes; validate coating consistency. |

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

ELISA technology continues to evolve with several transformative trends shaping its future applications. Digital ELISA platforms now enable single-molecule detection, dramatically improving sensitivity for low-abundance biomarkers [1]. Integration with microfluidics has miniaturized traditional ELISA formats into portable, point-of-care devices suitable for resource-limited settings [1]. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated development of rapid ELISA-based tests for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and antigens, demonstrating the methodology's adaptability to emerging public health threats [1].

Automation and artificial intelligence integration represent the next frontier in ELISA evolution. Automated systems with robotic liquid handling and advanced microplate readers now facilitate high-throughput screening while minimizing inter-assay variability [1]. Machine learning algorithms enhance data analysis through improved curve-fitting and outlier detection capabilities [1]. These advancements complement rather than replace traditional ELISA approaches, instead expanding the technique's applicability to increasingly complex research questions.

Despite the emergence of alternative proteomic technologies, ELISA maintains distinct advantages in scenarios requiring quantitative accuracy, regulatory compliance, and practical accessibility [2]. The methodology's established infrastructure, well-characterized validation parameters, and compatibility with clinical diagnostic frameworks ensure its continued relevance. Future developments will likely focus on enhancing multiplexing capabilities, reducing sample volume requirements, and integrating with complementary analytical platforms to address increasingly sophisticated research and diagnostic challenges.

The Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) is a foundational technique in biomedical research and diagnostic development, leveraging the specificity of antigen-antibody interactions coupled with enzymatic amplification for detection. For researchers and drug development professionals, a deep understanding of these core principles is not merely academic; it is a prerequisite for rigorous assay optimization, reliable data interpretation, and robust diagnostic or therapeutic outcomes. The fundamental process involves immobilizing an antigen on a solid surface, complexing it with an antibody linked to an enzyme, and then measuring the enzyme's activity via incubation with a substrate to produce a quantifiable product [7]. The exquisite specificity of the assay is governed by the molecular dynamics of immunochemical binding, while its sensitivity is derived from the catalytic power of the signal-generating enzyme. This application note delineates the underlying mechanisms and provides detailed protocols for their practical application in optimizing ELISA performance.

Molecular Basis of Antigen-Antibody Interactions

Structural Foundations of Specificity

The precise interaction between an antibody and its target antigen is a paradigm of molecular recognition. The binding site is formed by the hypervariable regions of the antibody's heavy and light chains, more accurately termed Complementarity-Determining Regions (CDRs). Each antibody possesses three CDRs per chain (CDR1, CDR2, and CDR3), which create a unique molecular surface complementary to the shape and chemical character of its specific antigenic determinant, or epitope [10]. The most significant diversity is concentrated in the CDR3 region, which plays a dominant role in defining binding specificity. The combination of heavy and light chain CDRs determines the final antigen specificity, a mechanism known as combinatorial diversity [10].

Chemical Forces and Binding Dynamics

Antigen-antibody binding is a reversible, non-covalent process mediated by a combination of weak chemical forces operating over extremely short ranges [11] [10]. The contribution of each force varies depending on the specific antibody-antigen pair.

- Electrostatic Interactions: These occur between charged amino acid side chains, forming salt bridges that can be disrupted by high salt concentrations or extreme pH [10].

- Hydrogen Bonds: These bonds bridge oxygen and/or nitrogen atoms, accommodating specific reactive groups and strengthening the overall interaction [11] [10].

- Van der Waals Forces: These short-range forces operate between closely fitting surfaces, requiring a tight complementary "lock-and-key" fit [11].

- Hydrophobic Interactions: These are formed when two hydrophobic surfaces come together to exclude water. The binding energy is proportional to the surface area hidden from water [10].

The strength of an individual antibody-antigen interaction is termed its affinity, often represented by the equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd). A lower Kd indicates a higher affinity and a stronger interaction [11]. In ELISA, where antibodies are often multivalent, the overall strength of binding is referred to as avidity, which is the cumulative effect of multiple affinity interactions.

Table 1: Chemical Forces in Antigen-Antibody Interactions

| Force Type | Molecular Basis | Impact on Binding | Susceptible Disruption Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrostatic | Attraction between oppositely charged ionic groups | Strong, long-range interaction; contributes significantly to specificity | High salt concentration, extreme pH |

| Hydrogen Bonding | Sharing of hydrogen between electronegative atoms | Strengthens binding; requires precise alignment of groups | Extreme pH, denaturing agents |

| Van der Waals | Fluctuating electrical charges between adjacent atoms | Very short-range; requires close surface complementarity | Detergents |

| Hydrophobic | Interaction of non-polar groups in aqueous solution | Strong contributor to binding energy; proportional to buried surface area | Detergents, organic solvents |

Principles of Enzymatic Detection

The Enzyme Conjugate as a Signal Amplifier

The detection moiety of an ELISA is typically an enzyme conjugated to a detection antibody. Common enzymes include Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) and Alkaline Phosphatase (AP). These enzymes act as powerful amplifiers; a single enzyme molecule can catalyze the conversion of many substrate molecules to a detectable product, thereby greatly enhancing the assay's sensitivity [7]. The choice of enzyme depends on the required sensitivity, the detection method, and the need to avoid endogenous enzyme activity in the sample.

Substrate Systems and Detection Modalities

The substrate chosen for the enzyme must yield a measurable signal. The most common detection modes are absorbance (colorimetric), fluorescence, and luminescence [3]. Colorimetric substrates are widely used due to their simplicity and cost-effectiveness, with absorbance read on a standard microplate reader. Fluorescence and chemiluminescence detection generally offer higher sensitivity [3].

Table 2: Common Enzyme-Substrate Systems in ELISA

| Enzyme | Common Substrates | Detection System | Typical Conjugate Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) | TMB (Tetramethylbenzidine), ABTS | Colorimetric | 20–200 ng/mL [7] |

| Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) | Enhanced Luminol | Chemiluminescent | 10–100 ng/mL [7] |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) | pNPP (p-Nitrophenyl Phosphate) | Colorimetric | 100–200 ng/mL [7] |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) | CDP-Star, CSPD | Chemiluminescent | 40–200 ng/mL [7] |

Experimental Protocol: Checkerboard Titration for ELISA Optimization

A critical step in developing a robust in-house ELISA, particularly in the sandwich format, is the optimization of key reagent concentrations. The checkerboard titration is an efficient experimental design that allows for the simultaneous optimization of two parameters, such as capture and detection antibody concentrations [7] [8].

1. Primary Objective: To determine the optimal concentrations of the capture antibody and detection antibody that yield a strong specific signal with low background noise.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Coating Buffer: (e.g., 0.2 M carbonate-bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.4)

- Wash Buffer: (e.g., PBS or Tris-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween 20)

- Blocking Buffer: (e.g., 1-5% BSA or non-fat dry milk in wash buffer)

- Capture Antibody: Serial dilutions prepared in coating buffer.

- Detection Antibody: Serial dilutions prepared in standard diluent/blocking buffer.

- Antigen: A known positive control sample at a medium concentration.

- Enzyme Conjugate: (e.g., Streptavidin-HRP, if using a biotinylated detection antibody).

- Substrate: Appropriate to the enzyme (e.g., TMB for HRP).

- Stop Solution: (e.g., 0.16 M sulfuric acid for TMB).

- 96-well microplate and microplate reader.

3. Procedural Workflow:

4. Detailed Methodology:

Step 1: Plate Coating (Variable: Capture Antibody Concentration)

- Prepare a dilution series of the capture antibody in coating buffer. The range should be based on the antibody type (see Table 3). For example, prepare concentrations of 1, 2, 4, 8, and 12 µg/mL for an affinity-purified monoclonal antibody [7].

- Dispense each concentration of capture antibody in a column of the 96-well plate (e.g., Column 1: 1 µg/mL, Column 2: 2 µg/mL, etc.). Include a control well with coating buffer only.

- Seal the plate and incubate overnight at 4°C or for 1-2 hours at 37°C.

Step 2: Washing

- Aspirate the coating solution and wash the plate 3-5 times with wash buffer (200-300 µL per well per wash) to remove unbound antibody.

Step 3: Blocking

- Add a sufficient volume (e.g., 200 µL) of blocking buffer to all wells.

- Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature or 37°C.

- Wash the plate as in Step 2.

Step 4: Antigen Incubation

- Add a fixed, known concentration of the target antigen (your positive control) to all wells. A volume of 100 µL is standard.

- Incubate for a fixed time (e.g., 2 hours at room temperature).

- Wash the plate as before.

Step 5: Detection Antibody Incubation (Variable: Detection Antibody Concentration)

- Prepare a dilution series of the detection antibody in blocking buffer. For an affinity-purified antibody, a range of 0.5 - 5 µg/mL is a good starting point [7].

- Dispense each concentration of detection antibody in a row of the plate (e.g., Row A: 0.5 µg/mL, Row B: 1 µg/mL, etc.).

- Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature.

- Wash the plate thoroughly.

Step 6: Enzyme Conjugate Incubation

- If the detection antibody is not directly conjugated, add the appropriate enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody or Streptavidin (if the detection antibody is biotinylated) at the manufacturer's recommended dilution or an optimized concentration (see Table 2).

- Incubate for 30-60 minutes at room temperature.

- Wash the plate exhaustively.

Step 7: Signal Development

- Add the enzyme substrate (e.g., 100 µL of TMB) to all wells.

- Incubate in the dark for a fixed period (e.g., 15-30 minutes).

- Stop the reaction by adding an equal volume of stop solution (e.g., 100 µL of 0.16 M H₂SO₄ for TMB).

Step 8: Data Analysis

- Read the absorbance immediately on a microplate reader at the appropriate wavelength (e.g., 450 nm for TMB).

- The optimal concentration pair is the one that gives the highest signal for the positive antigen sample with the lowest signal in the negative control (no antigen) wells, resulting in the highest signal-to-noise ratio.

Table 3: Recommended Antibody Concentration Ranges for Optimization

| Antibody Source | Coating Antibody Range (µg/mL) | Detection Antibody Range (µg/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| Polyclonal Serum | 5–15 | 1–10 [7] |

| Crude Ascites | 5–15 | 1–10 [7] |

| Affinity-Purified Polyclonal | 1–12 | 0.5–5 [7] |

| Affinity-Purified Monoclonal | 1–12 | 0.5–5 [7] |

Assay Validation and Data Analysis

Critical Validation Experiments

Once optimal conditions are identified, the assay must be validated to ensure accuracy and reliability for its intended use.

- Spike and Recovery: Assess the impact of the sample matrix (e.g., serum, cell lysate) on the detection of the analyte. A known amount of analyte is spiked into the sample matrix and a reference diluent. The recovery is calculated by comparing the measured concentration to the expected concentration. Ideal recovery is 80-120% [8] [9].

- Dilutional Linearity: Evaluate the assay's performance across the expected concentration range. A sample with a high analyte concentration is serially diluted. The measured concentrations should be proportional to the dilution factor, demonstrating that the assay accurately quantifies the analyte at different levels [8].

- Parallelism: This confirms that the antibody binding affinity is the same for the endogenous analyte in the sample and the purified standard used for the calibration curve. Serially dilute a sample with a high endogenous level of the analyte. The calculated concentrations after dilution should have a low coefficient of variation (%CV) [8].

Data Analysis and Standard Curve Fitting

For quantitative ELISAs, data are interpreted using a standard curve. The mean absorbance of duplicate or triplicate standards is plotted against their known concentrations [9]. The most appropriate curve-fitting model should be selected for optimal accuracy.

- Linear and Semi-log Plots: Simple but may compress data at the curve's extremes.

- 4- or 5-Parameter Logistic (4PL/5PL): These are the gold standard for immunoassays. The 4PL model assumes symmetry around the inflection point, while the 5PL accounts for asymmetry, often providing a superior fit [9].

The concentration of unknown samples is determined by interpolating their mean absorbance from the standard curve. Any sample falling outside the range of the standard curve should be re-assayed at an appropriate dilution [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Reagents for ELISA Development and Optimization

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Matched Antibody Pairs | A pair of monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies that bind distinct, non-overlapping epitopes on the target antigen for sandwich ELISA [7]. | Essential for specificity; requires empirical testing for pair compatibility. |

| Blocking Buffers (e.g., BSA, Casein) | Proteins or mixtures used to coat all remaining protein-binding sites on the plate after coating with the capture antibody, minimizing non-specific binding [12]. | Different blockers may be optimal for different antibody-antigen systems; testing is required to minimize background. |

| Microplates | Solid phase for immobilization of the capture antibody or antigen. | High protein-binding plates (e.g., polystyrene) are standard. |

| Enzyme Conjugates (HRP, AP) | Catalyze the conversion of a substrate into a detectable signal, providing assay sensitivity through amplification. | Concentration must be optimized to balance signal and background (see Table 2). |

| Chromogenic/Luminescent Substrates | Molecules converted by the enzyme conjugate to a colored, fluorescent, or luminescent product for detection. | Choice depends on required sensitivity and available detection instrumentation [3]. |

| Sample/Diluent Matrix | The solution used to dilute samples and standards. | Should mimic the sample matrix as closely as possible to avoid matrix effects (e.g., using serum diluent for serum samples) [7] [9]. |

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is a foundational plate-based technique designed for the detection and quantification of soluble substances such as peptides, proteins, antibodies, and hormones [13]. First described by Engvall and Perlmann in 1971, this powerful method enables the analysis of protein samples immobilized in microplate wells using specific antibodies, leveraging the high specificity of antibody-antigen interactions [13] [3]. The fundamental principle of ELISA relies on immobilizing an antigen of interest on a solid surface, complexing it with an antibody linked to a reporter enzyme, and detecting the activity of this enzyme via incubation with a substrate to produce a measurable product [7] [13].

ELISAs are particularly valued for their ability to measure specific analytes within crude preparations, achieved through the immobilization of reagents to the microplate surface, which facilitates easy separation of bound from non-bound material during washing steps [13]. The most common ELISA formats include direct, indirect, sandwich, and competitive assays, with the sandwich format being widely regarded as the most robust and sensitive for its use of two primary antibodies that bind distinct epitopes on the target antigen [7] [13]. This application note deconstructs the complete ELISA workflow, with a particular emphasis on the sandwich ELISA format, providing detailed methodologies and optimization strategies to support researchers in developing robust assays for research and development applications.

Key Stages of the ELISA Workflow

The ELISA procedure consists of several sequential stages, each critical to the assay's overall performance, specificity, and sensitivity. The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages of a sandwich ELISA, from plate preparation to data analysis.

Stage 1: Plate Coating and Capture

The initial stage of the ELISA workflow involves immobilizing either the antigen or a capture antibody onto the solid surface of a microplate well through passive adsorption driven by hydrophobic interactions between the plastic and non-polar protein residues [13].

- Coating Buffer Selection: The most common coating buffer is 0.2M carbonate/bicarbonate at pH 8.4-9.6, although phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or Tris-buffered saline (TBS) are sometimes used [14]. The alkaline pH facilitates optimal binding for many proteins.

- Coating Conditions: Proteins are typically diluted to a concentration of 2-10 μg/mL in coating buffer and added to the microplate wells [13]. Plates are then incubated for several hours to overnight at temperatures ranging from 4°C to 37°C [13].

- Alternative Coating Strategies: For oriented antibody binding, plates pre-coated with Protein A, Protein G, or streptavidin can be used, though these should be avoided in sandwich ELISA formats where detection antibodies might also bind to these proteins [14].

Stage 2: Blocking

Following plate coating, the blocking step is crucial to prevent non-specific binding that can cause high background signal. This process involves adding an irrelevant protein or other molecule to cover all remaining unsaturated surface-binding sites of the microplate wells [13].

- Blocking Reagents: Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) is widely used at concentrations of 1-5% [8]. Normal serums (typically 5% v/v) derived from non-immunized animals are also effective, particularly when diluted in the same host species as the labeled antibody to prevent antibody binding to conserved sequences and Fc-receptors [14].

- Quality Considerations: Commercial BSA preparations may contain contaminating bovine IgG or proteases that can cause background or degrade assay components. Selecting BSA certified as IgG- and protease-free is recommended [14].

- Optimization: Different blocking solutions and concentrations should be tested experimentally. Blocking is typically performed for 1-2 hours at room temperature following coating and prior to sample addition [7] [14].

Stage 3: Sample and Antibody Incubation

This stage encompasses the addition of the sample and the antibodies required for antigen capture and detection.

- Sample Considerations: Samples analyzed by ELISA vary extensively and can include cell lysates, cell culture supernatants, tissue homogenates, and bodily fluids such as serum, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid [14]. Proper sample handling is critical, including storage at -80°C, minimizing freeze-thaw cycles, and keeping samples on ice during use [14].

- Matrix Effects: The sample matrix can significantly affect assay readout. Spike-and-recovery experiments should be performed to assess matrix effects, where a known amount of analyte is added to both the sample matrix and the standard diluent, with ideal results showing little difference between the two conditions [8].

- Antibody Selection: For sandwich ELISAs, a matched antibody pair recognizing different epitopes on the target antigen is required [7]. A common strategy employs a monoclonal antibody for capture and a polyclonal antibody for detection [14].

Stage 4: Detection and Signal Development

Detection in ELISA can be categorized as colorimetric, fluorometric, or chemiluminescent, with the choice dictated by sensitivity requirements, multiplexing needs, and available instrumentation [14].

- Enzyme-Substrate Systems: Horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and alkaline phosphatase (AP) are the most commonly used enzyme labels [13]. The selection of substrate depends on the detection method required and the instrumentation available.

- Detection Methods:

- Colorimetric Detection: Provides a simple, cost-effective readout measured by absorbance. Common substrates include TMB (tetramethylbenzidine) for HRP and pNPP (p-Nitrophenyl Phosphate) for AP [14].

- Fluorometric Detection: Offers greater sensitivity and dynamic range than colorimetric methods, enabling multiplexing capabilities [14].

- Chemiluminescent Detection: Provides exceptional sensitivity and broad dynamic range but requires specialized reagents and instrumentation [14].

Table 1: Common Detection Systems in ELISA

| Detection Method | Enzyme | Common Substrates | Signal Measurement | Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorimetric | HRP | TMB, OPD, ABTS | Absorbance | Moderate |

| Colorimetric | AP | pNPP | Absorbance | Moderate |

| Fluorometric | HRP or AP | Fluorescent substrates | Fluorescence | High |

| Chemiluminescent | HRP | Luminol-based | Luminescence | Very High |

Stage 5: Data Analysis and Quantification

The final stage involves quantifying the target analyte by correlating the assay readout to a standard curve generated on the same microplate using known quantities of the target analyte [14] [15].

- Standard Curve: A dilution series of the target analyte of known concentration is run in parallel with samples to generate a standard curve, which is typically plotted using a 4-parameter logistic regression algorithm [8].

- Calculation: The amount of antigen in unknown samples is calculated by comparing their signal to the standard curve, with appropriate background subtraction and consideration of any dilution factors [8].

- Quality Assessment: The average, standard deviation, and coefficient of variation (%CV) should be determined for replicates to monitor assay performance and data integrity over time [8].

ELISA Optimization and Experimental Protocols

While commercial ELISA kits provide pre-optimized components, researchers developing custom ELISAs must systematically optimize each parameter to ensure robust performance. The following diagram illustrates the optimization workflow, highlighting key parameters requiring systematic evaluation.

Checkerboard Titration Protocol

A checkerboard titration is an efficient experimental approach to optimize multiple ELISA parameters simultaneously, particularly antibody concentrations [7] [8].

- Plate Setup: Prepare different concentrations of the capture antibody in coating buffer and apply equal volumes to the plate in a grid pattern.

- Detection Titration: Similarly, prepare different concentrations of the detection antibody.

- Assay Performance: Proceed with the ELISA protocol using a constant antigen concentration.

- Signal Assessment: Check for strong specific signal versus low background across the different concentration combinations.

- Optimal Concentration Selection: Identify the antibody concentrations that provide the optimal signal-to-noise ratio.

Key Optimization Parameters

Systematic optimization of the following parameters is essential for developing a robust ELISA:

- Antibody Concentrations: The table below provides recommended concentration ranges for coating and detection antibodies based on antibody type and purity [7].

Table 2: Recommended Antibody Concentration Ranges for ELISA Optimization

| Antibody Source | Coating Antibody Concentration | Detection Antibody Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| Polyclonal Serum | 5–15 μg/mL | 1–10 μg/mL |

| Crude Ascites | 5–15 μg/mL | 1–10 μg/mL |

| Affinity-Purified Polyclonal | 1–12 μg/mL | 0.5–5 μg/mL |

| Affinity-Purified Monoclonal | 1–12 μg/mL | 0.5–5 μg/mL |

- Incubation Conditions: Optimization of incubation time and temperature for coating, blocking, and antibody binding steps. While standard protocols often use room temperature incubations of 1-2 hours, some applications may benefit from extended incubations at 4°C [13].

- Wash Conditions: The choice of wash buffer, number of washes, and wash duration significantly impact background signal. Typically, PBS or TBS with 0.05% Tween-20 is used as a wash buffer [8].

- Enzyme Conjugate Concentration: The recommended concentration ranges for enzyme conjugates vary based on the detection system used, as shown in the table below [7].

Table 3: Recommended Enzyme Conjugate Concentrations for ELISA

| Enzyme | Detection System | Recommended Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| HRP | Colorimetric | 20–200 ng/mL |

| HRP | Chemifluorescent | 25–50 ng/mL |

| HRP | Chemiluminescent | 10–100 ng/mL |

| AP | Colorimetric | 100–200 ng/mL |

| AP | Chemiluminescent | 40–200 ng/mL |

Assay Validation Protocols

Comprehensive validation is essential to ensure ELISA accuracy, precision, and reliability for quantitative measurements.

Spike-and-Recovery Experiments:

- Add a known amount of purified analyte to both the sample matrix and the standard diluent.

- Run the ELISA and calculate the recovered concentration for both conditions.

- The percentage recovery should be between 80-120%, with little difference between matrix and diluent [8].

Dilutional Linearity:

- Serially dilute a sample containing a high concentration of the analyte.

- Analyze each dilution and calculate the observed concentration.

- The results should show linearity with the dilution factor, confirming consistent analyte detection across the assay range [8].

Parallelism Testing:

- Serially dilute samples with naturally high analyte concentrations.

- Calculate the concentration of each dilution and determine the coefficient of variation (%CV).

- A high %CV indicates potential matrix effects impacting antibody binding affinity [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful ELISA development and implementation requires careful selection of core components. The following table details essential materials and their functions in the ELISA workflow.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for ELISA Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Microplate | Solid phase for immobilization | Polystyrene, flat-bottom; clear for colorimetry, black/white for fluorescence/luminescence [14] [13] |

| Coating Antibody | Captures target antigen | Specificity, affinity, concentration (1-15 μg/mL depending on purity) [7] |

| Detection Antibody | Binds captured antigen | Recognizes different epitope than capture antibody; often enzyme-conjugated [7] |

| Blocking Buffer | Prevents non-specific binding | BSA (1-5%) or normal serum (5%); must be protein-rich [14] [13] |

| Coating Buffer | Stabilizes coating protein | Carbonate/bicarbonate (pH 9.4) or PBS (pH 7.4); protein-free [14] |

| Wash Buffer | Removes unbound reagents | PBS or TBS with 0.05% Tween-20 detergent [8] |

| Enzyme Conjugate | Signal generation | HRP or AP conjugated to detection antibody or secondary antibody [7] |

| Substrate | Enzyme converted to detectable product | Colorimetric, fluorogenic, or chemiluminescent based on detection needs [14] |

| Standards | Quantification reference | Known concentrations of pure analyte for standard curve generation [8] |

The ELISA workflow comprises multiple interconnected stages, each requiring careful optimization to achieve maximal assay performance. From initial plate coating and blocking to final data analysis, attention to technical details at each step is essential for developing a robust, sensitive, and reproducible assay. By systematically optimizing critical parameters such as antibody concentrations, incubation conditions, and detection systems through structured approaches like checkerboard titration, researchers can create ELISAs capable of precise protein quantification across diverse applications. The protocols and guidelines presented in this application note provide a framework for researchers to deconstruct and master each element of the ELISA workflow, supporting advancements in biomedical research, drug development, and diagnostic applications.

The Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) is a powerful, plate-based technique designed for detecting and quantifying soluble substances such as peptides, proteins, antibodies, and hormones [13]. Its fundamental principle relies on the highly specific interaction between an antigen and an antibody, where the antigen is immobilized on a solid surface and complexed with an antibody linked to a reporter enzyme [13]. Detection is accomplished by measuring the activity of this reporter enzyme via incubation with a substrate to produce a measurable product [13]. The performance of an ELISA is critically dependent on the careful selection and optimization of its core components: the solid phase, detection enzymes, substrates, and the reading instrument. Within the context of protocol optimization research, a systematic approach to evaluating these reagents and equipment is paramount for developing assays that are robust, sensitive, and reproducible, thereby providing reliable data for drug development and biomedical research.

Essential Reagents and Their Functions

Solid Phases: Microplates

The solid phase, typically a microplate, serves as the foundational support for the assay, facilitating the immobilization of reactants and the separation of bound from unbound material [13].

- Material and Binding: ELISA plates are usually made of polystyrene and facilitate the passive adsorption of proteins via hydrophobic interactions [13] [16]. This binding is a passive process, and the high protein-binding capacity of the plates is crucial for assay sensitivity.

- Plate Type: For colorimetric detection, clear polystyrene flat-bottom plates are used. For fluorescent or chemiluminescent signals, black or white opaque plates are employed to minimize cross-talk and light reflection [13].

- Selection Criteria: When selecting a plate, key parameters include a high protein-binding capacity (e.g., >400 ng/cm²) and a low coefficient of variation (CV <5%) to ensure well-to-well and plate-to-plate reproducibility [13]. Plates should be visually inspected for imperfections that could cause aberrations in data acquisition [13].

Enzymes and Substrates

The enzyme conjugate and its corresponding substrate form the core of the signal generation system in ELISA. The most commonly used enzyme labels are Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) and Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) [13] [17].

- Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP): A popular choice due to its high specific activity and rapid turnover. Its common substrates include:

- Alkaline Phosphatase (AP): Known for its stability and linear kinetics. A common substrate is pNPP (p-Nitrophenyl Phosphate), which yields a yellow colorimetric product measurable at 405-410 nm [17].

The choice between a colorimetric, chemiluminescent, or fluorescent substrate depends on the required assay sensitivity and the available detection instrumentation [13]. Chemiluminescent substrates generally offer the highest sensitivity [7].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

A successful ELISA requires a suite of carefully formulated buffers and reagents. The table below summarizes the essential materials and their functions.

Table 1: Essential Reagents for ELISA Development and Optimization

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in the Assay |

|---|---|---|

| Coating Buffer | Carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.4), PBS (pH 7.4) [13] | Provides optimal pH and ionic conditions for passive adsorption of antigen or capture antibody to the plate. |

| Blocking Buffer | PBS with 0.1% BSA and 0.05% Tween 20 [16] | Saturates all remaining protein-binding sites on the plate to minimize non-specific binding and reduce background signal. |

| Wash Buffer | PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 [16] | Removes unbound reagents and weakly associated molecules during the washing steps; Tween 20 blocks newly exposed sites. |

| Sample Diluent | Incubation buffer (for cell culture supernatants), specialized ELISA diluent (for serum/plasma) [16] | Dilutes samples and standards in a matrix that mimics the sample to prevent interference and maintain antibody-antigen binding. |

| Detection Antibodies | Biotinylated primary antibody, Enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody, Streptavidin-HRP [16] [7] | Binds specifically to the captured antigen (directly or indirectly) and carries the enzyme label for signal generation. |

| Enzyme Conjugate | Streptavidin-HRP, Anti-species IgG-HRP [7] | Provides the catalytic enzyme (e.g., HRP, AP) that converts the substrate into a detectable signal. |

| Stop Solution | 0.16 M Sulfuric Acid [7] | Halts the enzyme-substrate reaction abruptly at a defined endpoint, stabilizing the signal for measurement. |

Experimental Protocols for Optimization

Protocol optimization is a systematic process to ensure the assay delivers strong, specific signals with low background. The following methodologies are critical for this process.

Checkerboard Titration for Reagent Optimization

A checkerboard titration is an efficient experimental design used to optimize the concentrations of two key reagents simultaneously, such as the capture and detection antibodies [7].

Detailed Protocol:

- Prepare Capture Antibody Dilutions: Dilute the capture antibody in coating buffer across a range of concentrations (e.g., 1-15 µg/mL, depending on source and purity) [7]. Dispense different concentrations in rows of the microplate.

- Coat and Block: Incubate the plate overnight at 4°C, then wash and block the plate using a standard blocking buffer.

- Add Antigen: Add a fixed, known concentration of the target antigen (a purified standard) to all wells.

- Prepare Detection Antibody Dilutions: Dilute the detection antibody in standard diluent across a range of concentrations (e.g., 0.5-10 µg/mL) [7]. Dispense different concentrations in columns of the microplate.

- Complete the Assay: Incubate, wash, and then add the enzyme conjugate (if the detection antibody is not directly conjugated) and substrate following standard procedures.

- Data Analysis: Measure the signal. The optimal combination is the lowest concentration of both antibodies that yields the highest signal-to-noise ratio (strong signal with low background) [7].

Protocol for Assay Validation: Spike-and-Recovery

The spike-and-recovery experiment determines if components in the sample matrix (e.g., serum, cell culture media) interfere with the detection of the target analyte [9].

Detailed Protocol:

- Prepare Spiked Samples: Spike a known concentration of the purified standard protein into both the sample matrix of interest and a standard diluent (e.g., assay buffer). Prepare multiple dilutions.

- Prepare Control Samples: Include a non-spiked sample of the matrix and the diluent as background controls.

- Run the ELISA: Analyze all samples using the optimized ELISA protocol.

- Calculate Percent Recovery: For each spiked sample, use the formula:

- % Recovery = (Measured concentration in spiked matrix / Measured concentration in spiked diluent) × 100

- Interpretation: Recovery values between 80% and 120% are generally acceptable, indicating minimal matrix interference. If recovery is outside this range, the sample matrix may require further dilution, or the standard curve may need to be prepared in the same matrix [9].

Data Analysis and Standard Curve Generation

Accurate quantification in a quantitative ELISA requires the generation of a standard curve from which the concentration of unknown samples is extrapolated [9] [18].

Detailed Protocol:

- Serial Dilution: Perform a serial dilution of the purified antigen standard in the chosen diluent to generate a range of known concentrations.

- Run Standards and Samples: Analyze the standard dilutions and unknown samples in duplicate or triplicate.

- Plot and Curve Fit: Plot the mean absorbance (y-axis) against the protein concentration (x-axis). Use appropriate curve-fitting models:

- Calculate Unknowns: For each unknown sample, find its average absorbance on the y-axis, extend a horizontal line to the standard curve, and then a vertical line down to the x-axis to read the corresponding concentration. Multiply by the dilution factor if the sample was diluted [9] [18].

- Assess Precision: Calculate the coefficient of variation (CV) for sample duplicates. A CV of ≤20% is typically acceptable, with larger values indicating inconsistency or error [9] [18].

Table 2: Recommended Concentrations for ELISA Optimization

| Reagent | Source | Recommended Optimization Range | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coating Antibody | Affinity-purified polyclonal or monoclonal | 1 - 12 µg/mL [7] | Use purified antibodies for optimal signal-to-noise ratio. |

| Detection Antibody | Affinity-purified polyclonal or monoclonal | 0.5 - 5 µg/mL [7] | Must be specific for the primary antibody (in indirect/detection). |

| HRP Conjugate | Colorimetric System | 20 - 200 ng/mL [7] | Concentration must be compatible with the substrate's range. |

| AP Conjugate | Colorimetric System | 100 - 200 ng/mL [7] | Known for stable, linear reaction kinetics. |

Workflow and Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision-making process involved in optimizing and executing a sandwich ELISA, from initial setup to data analysis.

ELISA Optimization and Execution Workflow

The relationships between core ELISA reagents and the resulting signal are fundamental to the assay's function. The diagram below depicts this critical signaling pathway.

ELISA Signal Generation Pathway

Advanced Methodologies and Practical Application Strategies

The Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) remains a cornerstone technology for detecting and quantifying target analytes within complex biological samples. The selection of an appropriate assay format—direct, indirect, sandwich, or competitive—is a critical determinant of experimental success, impacting sensitivity, specificity, workflow efficiency, and data accuracy. This application note provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of these core ELISA formats, underpinned by current optimization research. We present structured quantitative data, detailed experimental protocols, and best-practice reagent specifications to guide researchers and drug development professionals in selecting and optimizing the most suitable ELISA configuration for their specific application needs, thereby enhancing the reliability and reproducibility of data within rigorous scientific and regulatory frameworks.

The fundamental principle of ELISA involves the immobilization of an antigen (Ag) or antibody (Ab) onto a solid phase (typically a polystyrene microplate), followed by a series of binding and amplification steps that ultimately generate a measurable signal proportional to the analyte concentration [13] [4]. The specificity of the assay is conferred by robust antigen-antibody interactions, while sensitivity is achieved by conjugating enzymes, such as Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) or Alkaline Phosphatase (AP), to antibodies or antigens. These enzymes catalyze the conversion of a substrate into a colored, fluorescent, or luminescent product that can be quantified spectrophotometrically [19] [13]. The versatility of ELISA is demonstrated by its compatibility with diverse sample matrices, including serum, plasma, cell culture supernatants, saliva, and tissue lysates [19]. The evolution of the technique from its inception in the 1970s has led to the development of multiple formats, each with distinct advantages and limitations, making format selection a primary consideration in assay design [4].

Comparative Analysis of ELISA Formats

The four principal ELISA formats—direct, indirect, sandwich, and competitive—differ in their configuration of antibody-antigen interactions, which directly influences their application-specific performance. The table below provides a structured comparison of these core characteristics.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Core ELISA Formats

| Format | Key Principle | Best Applications | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct ELISA [19] [20] | A labeled primary antibody binds directly to the immobilized antigen. | Assessing antibody affinity and specificity; blocking/inhibitory studies [19]. | Fast, simple protocol; minimal steps; reduced cross-reactivity risk [19] [13]. | Lower sensitivity; potential for high background; limited antibody options [19] [20]. |

| Indirect ELISA [19] [13] | An unlabeled primary antibody binds the antigen, and is detected by a labeled secondary antibody. | Detecting endogenous antibodies (e.g., serological testing) [19] [21]. | High sensitivity due to signal amplification; versatile; wide range of available secondary antibodies [19] [20]. | Risk of cross-reactivity from secondary antibody; longer protocol [19] [13]. |

| Sandwich ELISA [19] [7] | The antigen is captured between a surface-bound antibody and a detection antibody. | Quantifying specific antigens in complex samples (e.g., cytokines, biomarkers) [19] [21]. | High sensitivity and specificity; compatible with complex samples; no sample purification required [19] [22]. | Requires two matched antibodies; longer development time; challenging to optimize [19] [20]. |

| Competitive ELISA [19] [20] | Sample antigen and labeled antigen compete for a limited number of antibody binding sites. | Quantifying small molecules (e.g., hormones, drugs, contaminants) [19] [21]. | Ideal for small antigens; robust with complex samples; flexible format [19] [20]. | Lower sensitivity; signal is inversely proportional to analyte; requires optimization [19] [20]. |

The strategic selection among these formats hinges on the molecular characteristics of the analyte (e.g., size, availability of epitopes), the required sensitivity and specificity, and the available reagents. The trend in next-generation ELISA (ELISA 2.0) is toward digital detection, single-molecule sensing (e.g., digital ELISA), and multiplexing to overcome the limitations of traditional formats, offering ultra-sensitive, high-throughput analysis crucial for advanced diagnostics and biopharmaceutical quality control [23].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

A successful ELISA requires a meticulously optimized, step-by-step protocol. The following sections detail the standard workflows for the two most common formats: Sandwich and Competitive ELISA.

Detailed Protocol: Sandwich ELISA

The sandwich ELISA is the preferred format for quantifying specific proteins and biomarkers due to its superior specificity [7] [22].

Workflow Overview:

Sandwich ELISA Workflow

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Plate Coating: Dilute the capture antibody in a coating buffer (e.g., carbonate-bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.4 or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4) to a concentration typically between 1–15 µg/mL, with affinity-purified antibodies often optimal at 1–12 µg/mL [7] [13]. Dispense 100 µL/well into a 96-well microplate. Seal the plate and incubate for a minimum of 2 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C.

Blocking: Aspirate the coating solution. Wash the plate three times with 300 µL/well of wash buffer (e.g., PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20, PBST). Add 200–300 µL/well of blocking buffer (e.g., 1–5% BSA or 5% non-fat dry milk in PBST) to cover all unsaturated binding sites. Incubate for 1–2 hours at room temperature [7] [8].

Sample and Standard Incubation: Aspirate the blocking buffer and wash the plate 3 times. Prepare serial dilutions of the protein standard in a diluent that closely matches the sample matrix (e.g., cell culture medium, assay buffer) [7]. Add 100 µL/well of standards, controls, and test samples. Incubate for 1–2 hours at room temperature to allow antigen capture.

Detection Antibody Incubation: Wash the plate 3–5 times to remove unbound antigen. Add 100 µL/well of the biotinylated or enzyme-conjugated detection antibody, diluted in diluent to a concentration of 0.5–10 µg/mL [7]. Incubate for 1–2 hours at room temperature.

Enzyme Conjugate Incubation: Wash the plate as before. If using a biotinylated detection antibody, add 100 µL/well of Streptavidin-HRP conjugate diluted in diluent to the recommended concentration (e.g., 20–200 ng/mL for HRP colorimetric systems) [7]. Incubate for 30–60 minutes at room temperature, protected from light.

Signal Development: Perform a final wash step (5 times is recommended). Add 100 µL/well of a suitable substrate solution (e.g., TMB for HRP). Incubate for 5–30 minutes at room temperature, protected from light, until optimal color development is achieved.

Signal Detection and Analysis: Stop the enzyme-substrate reaction by adding 50–100 µL/well of stop solution (e.g., 0.16M sulfuric acid for TMB) [7]. Immediately measure the absorbance at the appropriate wavelength (e.g., 450 nm for TMB) using a microplate reader. Generate a standard curve by plotting the mean absorbance versus the standard concentration using a 4-parameter logistic (4-PL) regression model to interpolate sample concentrations [8].

Detailed Protocol: Competitive ELISA

Competitive ELISA is primarily used for measuring small molecules and hormones that are too small to be bound by two antibodies simultaneously [19] [20].

Workflow Overview:

Competitive ELISA Workflow

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Plate Coating: Coat the microplate with a known quantity of purified antigen (typically 2–10 µg/mL in coating buffer) [13] [20]. Incubate and wash as described in the sandwich protocol.

Blocking: Block the plate with an appropriate protein-based blocking buffer to prevent non-specific binding.

Competitive Incubation: Pre-incubate a constant, limited concentration of the enzyme-labeled antibody with serially diluted samples or standards containing the target antigen. Then, add this mixture to the antigen-coated plate. Alternatively, the labeled antibody can be added directly to the wells simultaneously with the sample. The key principle is that the antigen in the sample and the immobilized antigen compete for binding sites on the labeled antibody [19] [20]. Incubate for 1–2 hours at room temperature.

Wash: Wash the plate thoroughly to remove any unbound labeled antibody. The amount of antibody bound to the plate is inversely proportional to the concentration of antigen in the sample.

Signal Development and Detection: Add substrate solution to develop the signal. Stop the reaction and read the absorbance. Higher analyte concentration in the sample results in less antibody bound to the plate and, consequently, a lower signal [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The consistency and performance of an ELISA are dependent on the quality and optimization of its core components. The following table outlines the essential reagents required.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ELISA Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Specifications & Best Practices |

|---|---|---|

| Microplate [13] | Solid phase for immobilization of capture antibody or antigen. | Use high-protein-binding polystyrene plates (clear for colorimetric, white/black for chemiluminescent/fluorescent); ensure low well-to-well variation (CV <5%). |

| Coating Antibody [7] | Binds and immobilizes the target antigen from the sample. | Use affinity-purified antibodies; optimize concentration (1–12 µg/mL for purified monoclonals/polyclonals); select an antibody with high affinity and specificity. |

| Detection Antibody [7] [22] | Binds to a different epitope on the captured antigen. | Must be a matched pair with the capture antibody; can be biotinylated or directly conjugated to an enzyme (e.g., HRP); optimize concentration (0.5–5 µg/mL for purified antibodies). |

| Blocking Buffer [7] [8] | Covers unsaturated binding sites to minimize non-specific background signal. | Common agents: 1–5% BSA, 5% non-fat dry milk, or serum in PBST; requires empirical testing for optimal performance with specific antibody-antigen pairs. |

| Enzyme Conjugate [7] | Catalyzes the substrate to generate a detectable signal. | Common enzymes: HRP and Alkaline Phosphatase (AP). Optimize concentration (e.g., 20–200 ng/mL for HRP colorimetric). Streptavidin-HRP is used with biotinylated detection antibodies. |

| Substrate [13] | Converted by the enzyme into a measurable product. | TMB (colorimetric, HRP) is common. For higher sensitivity, use chemiluminescent substrates. Ensure compatibility with the enzyme and detection instrument. |

| Wash Buffer [4] | Removes unbound reagents and reduces background. | Typically PBS or Tris-based buffer with a surfactant (e.g., 0.05% Tween 20). Sufficient wash volume and cycles (3-5x) are critical for low background. |

Critical Protocol Optimization and Validation

Assay development does not end with establishing a workflow; rigorous optimization and validation are imperative for generating reliable, reproducible data, particularly in a drug development context.

Optimization via Checkerboard Titration

A checkerboard titration is the most efficient method for simultaneously optimizing the concentrations of the capture and detection antibodies [7] [8]. Prepare a series of dilutions of the capture antibody and coat them across the plate in rows. Similarly, prepare dilutions of the detection antibody and add them down the columns. After running the assay, analyze the signal-to-background ratio for each well. The optimal condition is the combination of antibody concentrations that yields the strongest specific signal with the lowest background, providing the widest assay dynamic range [7].

Essential Validation Experiments

- Spike and Recovery: Assess the impact of the sample matrix by spiking a known amount of the analyte into the sample matrix and a reference diluent. Calculate the percentage recovery; ideal recovery is 80–120%, indicating minimal matrix interference [8].

- Dilutional Linearity: Serially dilute a sample with a high endogenous concentration of the analyte. The measured concentrations, when corrected for dilution, should be constant. A loss of linearity indicates matrix effects or assay hook effect, necessitating further optimization of the sample diluent [8].

- Parallelism: Compare the standard curve diluted in assay buffer to the standard curve diluted in a matrix similar to the sample (e.g., normal serum). The curves should be parallel, confirming that the antibody affinity is similar for the standard and the endogenous analyte [8].

The strategic selection and meticulous optimization of an ELISA format are foundational to successful research and assay development. The direct and indirect formats offer simplicity and speed for specific applications, while the sandwich ELISA provides unparalleled specificity for quantifying proteins in complex matrices. The competitive format is indispensable for the analysis of small molecules. The ongoing evolution of ELISA, through advancements in detection chemistry, multiplexing, and automation (ELISA 2.0), continues to expand its utility in biomarker discovery, diagnostics, and biopharmaceutical quality control [23]. By adhering to the detailed protocols, optimization strategies, and validation practices outlined in this document, scientists can ensure their ELISA methods are robust, sensitive, and fit-for-purpose.

The Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) remains a cornerstone technique for the quantitative detection of proteins, peptides, antibodies, and hormones in biological samples [4]. Its robustness, however, is critically dependent on meticulous optimization of key procedural steps to ensure high sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility. Within the broader context of ELISA protocol optimization research, this application note delineates three fundamental checkpoints: antibody coating, blocking buffers, and sample diluents. Failures at any of these stages can manifest as excessive background noise, diminished signal strength, poor precision, or inaccurate quantification, ultimately compromising data integrity [14] [7]. This guide provides detailed methodologies and data-driven recommendations to empower researchers in systematically optimizing these parameters for robust assay performance.

Antibody Coating Optimization

The initial immobilization of the capture antibody onto the microplate surface is the foundation of a sandwich ELISA. Passive adsorption via hydrophobic interactions is the most common method, and its efficiency dictates the assay's ultimate capacity [14].

Coating Buffer Composition and pH

The choice of coating buffer is paramount for stabilizing the biomolecule and facilitating its binding to the polystyrene plate. A summary of common coating buffers is provided in Table 1.

Table 1: Common Coating Buffers for ELISA

| Buffer Type | Typical Composition | Optimal pH Range | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbonate/Bicarbonate | 0.2 M carbonate/bicarbonate [14] | 8.4 - 9.6 [14] | Most common; high pH enhances hydrophobic binding for many proteins. pH choice depends on protein isoelectric point [14]. |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) | 10 mM phosphate, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl [24] | 7.2 - 7.4 [24] | Physiological pH; suitable for some antibodies and antigens sensitive to alkaline conditions. |

| Tris-Buffered Saline (TBS) | 25 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl [24] | 7.2 - 7.4 [24] | Alternative to PBS; note that phosphate can interfere with alkaline phosphatase (AP)-based detection systems [25]. |

Critical Consideration: The coating buffer must be protein-free to prevent competitive binding of extraneous proteins to the plate, which becomes a significant source of non-specific background [14].

Experimental Protocol: Checkerboard Titration for Coating and Detection Antibodies

A checkerboard titration is the most efficient method to simultaneously optimize the concentrations of both the capture and detection antibodies [7] [8].

Materials:

- Purified capture antibody

- Coating buffer (e.g., Carbonate-Bicarbonate, pH 9.6)

- Blocking buffer (e.g., 5% BSA or commercial blocker)

- Antigen standard

- Detection antibody (biotinylated or directly conjugated)

- Wash buffer (e.g., PBS or TBS with 0.05% Tween-20)

- Enzyme conjugate (e.g., Streptavidin-HRP)

- Substrate and Stop solution

Method:

- Prepare Capture Antibody Dilutions: Dilute the capture antibody in coating buffer across a range of concentrations (e.g., 1-15 µg/mL for affinity-purified antibodies) [7].

- Coat Plate: Add different concentrations of the capture antibody to the microplate wells in a grid pattern. Incubate overnight at 4°C or for 1-3 hours at 37°C.

- Wash and Block: Wash the plate 2-3 times with wash buffer. Add a sufficient volume of blocking buffer and incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature.

- Add Antigen: Wash the plate. Add a fixed, known concentration of the antigen standard to all wells.

- Prepare Detection Antibody Dilutions: Dilute the detection antibody in blocking or assay buffer across a range of concentrations.

- Detect: Wash the plate. Add different concentrations of the detection antibody to the plate in an orthogonal grid pattern relative to the capture antibody. Incubate and wash.

- Complete Assay: Add the enzyme conjugate, incubate, wash, and then add substrate. Finally, stop the reaction and read the absorbance.

Data Analysis: The optimal condition is the pair of the lowest antibody concentrations that yields the highest signal-to-noise ratio (i.e., strong positive signal with low background in negative controls) [7].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key decision points for optimizing the three critical checkpoints described in this application note.

Blocking Buffer Selection

After coating, any remaining protein-binding sites on the polystyrene plate must be blocked to prevent non-specific adsorption of assay components, a major contributor to high background signal [14] [25].

Types of Blocking Buffers

No single blocking agent is ideal for every application, as each antibody-antigen pair has unique characteristics [25]. The choice often involves a trade-off between blocking efficiency and potential interference with antigen-antibody binding. Key options are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Common Blocking Buffers for ELISA

| Blocking Agent | Typical Concentration | Benefits | Considerations and Potential Interferences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | 1-5% [25] | Highly purified, inexpensive, compatible with biotin-streptavidin systems and phosphoprotein detection [25] [24]. | Generally a weaker blocker than others, which can result in more non-specific binding. Commercial preparations may contain contaminating bovine IgG and proteases [14]. |

| Non-Fat Dry Milk | 2-5% [25] | Inexpensive and effective; contains multiple protein types. | Contains biotin and phosphoproteins, which can interfere with streptavidin-biotin detection and phospho-protein analysis [25]. May mask some antigens. |

| Normal Sera | 2-5% v/v [14] [26] | Excellent for preventing antibody binding to conserved sequences and Fc-receptors. Best if from the same species as the labeled antibody [14]. | Risk of falsely elevated signal if the primary antibody binds to a serum protein [14]. Can be more variable. |

| Casein | 1-2% [25] [24] | Single purified protein; fewer cross-reactions than milk. Good high-performance replacement for milk [24]. | More expensive than milk or BSA. |

| Protein-Free Blockers | Ready-to-use [24] [26] | Contains no animal proteins; ideal for eliminating cross-reactivity from antibodies reacting with blocking proteins. Minimizes background in sensitive assays [24] [26]. | Can be more costly. Performance is formulation-dependent. |

Experimental Protocol: Comparing Blocking Buffer Efficacy

Materials:

- Coated and washed microplate

- Candidate blocking buffers (e.g., 5% BSA, 5% Non-Fat Milk, 1% Casein, Commercial Protein-Free blocker)

- Antigen standard

- Detection system (antibodies, conjugate, substrate)

Method:

- Divide Plate: After coating and washing, divide the plate into sections for each blocking buffer to be tested.

- Block: Add the different blocking buffers to their respective sections. Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature.