ELISA vs Flow Cytometry: A Comprehensive Guide to Immunochemical Methods for Biomedical Research

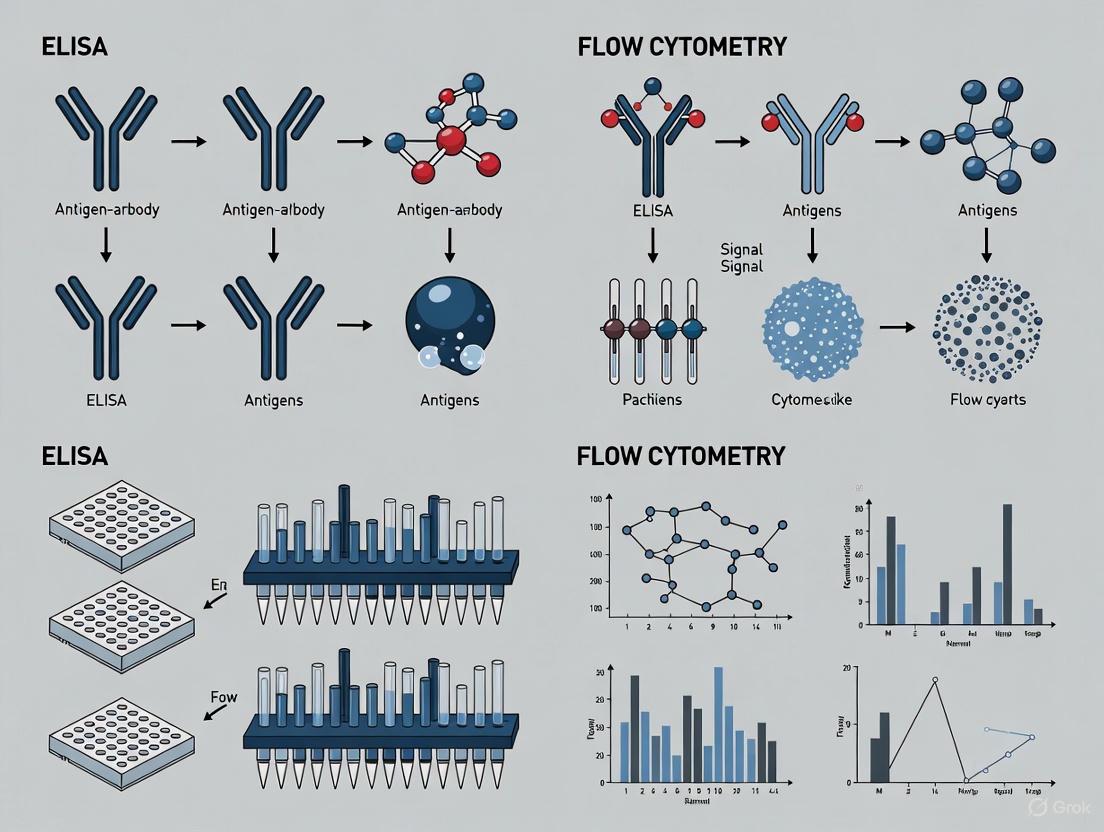

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a thorough exploration of two cornerstone immunochemical techniques: Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) and Flow Cytometry.

ELISA vs Flow Cytometry: A Comprehensive Guide to Immunochemical Methods for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a thorough exploration of two cornerstone immunochemical techniques: Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) and Flow Cytometry. It covers foundational principles, from the quantitative nature of ELISA for soluble molecules to the multi-parametric, single-cell analysis capabilities of flow cytometry. The article delivers detailed methodological protocols, expert troubleshooting advice, and rigorous validation approaches. By presenting a clear comparative analysis, this resource empowers professionals to select the optimal method based on their specific research questions, sample types, and project requirements, ultimately enhancing experimental design and data reliability in immunology, oncology, and drug development.

Core Principles: Understanding the Fundamentals of ELISA and Flow Cytometry

What is ELISA? Defining the Plate-Based Assay for Quantifying Soluble Targets

The Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) is a fundamental pillar in immunochemical methods, serving as a powerful plate-based technique designed for detecting and quantifying soluble substances such as peptides, proteins, antibodies, and hormones [1]. First described by Eva Engvall and Peter Perlmann in 1971, ELISA was developed as a safer alternative to radioimmunoassay (RIA), replacing radioactive labels with enzymes to generate a detectable signal [2] [3]. This innovation paved the way for a versatile and widely adopted technology.

The core principle of ELISA hinges on the specificity of antibody-antigen interactions, coupled with an enzymatic reaction for signal amplification [4] [5]. In essence, one of the immunoreactants is immobilized on a solid surface, typically a polystyrene microtiter plate. Subsequent binding events are then revealed through an enzyme-conjugated antibody that, when incubated with its substrate, produces a measurable colorimetric, fluorescent, or chemiluminescent signal [2] [3]. The intensity of this signal is proportional to the concentration of the target analyte in the sample [5].

ELISA's significance extends across diverse fields. In research laboratories, it is an indispensable tool for quantifying protein levels and analyzing pathway activation [4]. In clinical diagnostics, it is used for detecting infections, autoantibodies, tumor markers, and hormones [2]. Furthermore, its applications encompass drug development, environmental monitoring, and food safety testing [5], solidifying its status as a cornerstone technique in the scientist's toolkit.

Core Principles and Key Components

The robustness of ELISA stems from the seamless integration of immunology and biochemistry. The assay's functionality relies on several key components and principles that work in concert.

- Antibody-Antigen Specificity: The foundation of any ELISA is the highly specific lock-and-key interaction between an antibody and its target antigen. This specificity allows for the precise identification and measurement of a single analyte within a complex mixture, such as serum or cell lysate [1].

- Solid-Phase Separation: As a heterogeneous assay, ELISA requires the separation of bound and free reagents. This is achieved by immobilizing the capture molecule (antigen or antibody) onto a solid surface, most commonly a 96-well microplate [2]. This immobilization facilitates a series of simple washing steps to remove unbound material, thereby reducing background noise and enhancing assay specificity [1].

- Enzymatic Signal Amplification: To detect the often minute quantities of a target analyte, ELISA employs an enzyme (e.g., Horseradish Peroxidase - HRP, or Alkaline Phosphatase - AP) conjugated to a detection antibody [4] [2]. When a substrate is added, the enzyme catalyzes its conversion into a measurable product. A single enzyme can generate many thousands of product molecules, providing significant signal amplification and granting ELISA its exceptional sensitivity [3].

The graph above illustrates the core signaling principle of a sandwich ELISA. The target antigen is specifically captured and bound by antibodies. An enzyme-linked detection antibody then binds, and the introduction of a substrate triggers an enzymatic reaction that generates an amplified, measurable signal. This cascade ensures that even low-abundance targets can be detected with high sensitivity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

A successful ELISA depends on a set of well-characterized reagents. The table below details the essential materials and their critical functions within the assay.

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ELISA

| Component | Function | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Solid-Phase Microplate | Provides a surface for immobilizing capture molecules; facilitates separation and washing [1]. | 96-well or 384-well polystyrene plates [4]. |

| Capture & Detection Antibodies | Provide specificity by binding to the target analyte. The detection antibody is often enzyme-conjugated [4] [1]. | Monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies; matched antibody pairs for sandwich ELISA [4]. |

| Coating Buffer | Solution used to immobilize the antigen or capture antibody onto the plate surface [1]. | Carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.4) or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) [1]. |

| Blocking Buffer | Covers any remaining protein-binding sites on the plate to prevent non-specific binding of other reagents [2]. | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), casein, or other animal proteins [2] [3]. |

| Enzyme Conjugate | Catalyzes the conversion of a substrate into a detectable product, enabling signal amplification [4] [2]. | Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) or Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) [1]. |

| Detection Substrate | Compound acted upon by the enzyme to generate a measurable signal (color, light, or fluorescence) [4]. | TMB (colorimetric for HRP), pNPP (colorimetric for AP) [2]. |

Types of ELISA and Their Methodologies

ELISA can be configured in several formats, each with unique methodologies, advantages, and applications. The choice of format depends on the nature of the analyte, the antibodies available, and the required sensitivity.

Direct ELISA

The direct ELISA is the simplest format, involving a single enzyme-conjugated antibody that binds directly to the target antigen [2].

- Procedure:

- Coating: The antigen is immobilized directly onto the microplate well through passive adsorption [4] [3].

- Blocking: The plate is treated with a blocking protein (e.g., BSA) to prevent non-specific binding in subsequent steps [2].

- Detection: An enzyme-conjugated primary antibody specific to the antigen is added. After incubation and washing, the substrate is added to produce a signal [4] [2].

- Advantages: The protocol is rapid due to fewer steps, and it eliminates potential cross-reactivity from a secondary antibody [1] [2].

- Disadvantages: It has relatively lower sensitivity because there is no signal amplification step. It also requires a specifically conjugated primary antibody for each target, which can be costly and time-consuming to prepare [1]. This method is best suited for applications like immunosorbent staining of tissues and cells, or for detecting high-abundance antigens [1].

Indirect ELISA

The indirect ELISA introduces a secondary antibody for detection, which enhances the assay's flexibility and sensitivity [4] [2].

- Procedure:

- Coating and Blocking: These initial steps are identical to the direct ELISA [4].

- Primary Antibody Incubation: An unlabeled, antigen-specific primary antibody is added and binds to the antigen.

- Secondary Antibody Incubation: An enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody, which is specific to the species and isotype of the primary antibody, is added. This secondary antibody binds to the primary antibody.

- Signal Detection: After washing, the substrate is added to generate a signal [4] [2].

- Advantages: This format offers significant signal amplification, as multiple secondary antibodies can bind to a single primary antibody [1]. It is highly versatile, as the same labeled secondary antibody can be used with various primary antibodies from the same host species [1]. It also preserves the immunoreactivity of the primary antibody since it is not conjugated [1].

- Disadvantages: The additional incubation step increases the total assay time, and there is a risk of cross-reactivity if the secondary antibody binds non-specifically [1]. Indirect ELISA is widely used for screening antibodies, such as in serological tests for infectious diseases like HIV and Lyme disease [2].

Sandwich ELISA

The sandwich ELISA is the most sensitive and specific format. It requires two antibodies that bind to distinct, non-overlapping epitopes on the target antigen, "sandwiching" it in between [4] [2].

- Procedure:

- Capture Antibody Coating: A capture antibody, specific to the target antigen, is immobilized on the microplate well.

- Blocking: The plate is blocked to prevent non-specific binding.

- Sample Incubation: The test sample containing the antigen is added. The antigen binds to the capture antibody.

- Detection Antibody Incubation: An enzyme-conjugated detection antibody, specific to a different epitope on the antigen, is added to form the sandwich complex.

- Signal Detection: After a final wash, the substrate is added to produce a measurable signal [4] [1] [2].

- Advantages: This format offers high sensitivity and specificity because two antibodies are required for detection, minimizing false positives [1]. It is particularly well-suited for complex samples, as the antigen does not need to be purified before the assay [4].

- Disadvantages: It requires a "matched pair" of antibodies that recognize different epitopes, which can be expensive and require significant optimization [4] [1]. Sandwich ELISA is the format of choice for quantifying biomarkers, cytokines, and hormones in clinical and research settings [4] [2].

Competitive/Inhibition ELISA

The competitive ELISA is typically used for measuring small molecules or analytes with only a single epitope. In this format, the signal generated is inversely proportional to the concentration of the target in the sample [4] [1].

- Procedure:

- Antibody Coating: A specific capture antibody is immobilized on the plate.

- Competitive Incubation: The sample antigen and a known amount of enzyme-conjugated antigen are added simultaneously to the well. The two compete for a limited number of binding sites on the capture antibody.

- Signal Detection: The plate is washed, and substrate is added. A lower signal indicates a higher concentration of the target antigen in the sample, as it has out-competed the conjugated antigen for antibody binding [1].

- Advantages: This method is highly suitable for small antigens that cannot accommodate two antibodies simultaneously [4]. It is also less susceptible to sample matrix effects and can be used with partially purified samples [2].

- Disadvantages: It may have lower specificity compared to sandwich ELISA, and the dynamic range can be narrower [2]. Competitive ELISA is often used to measure hormone levels, therapeutic drugs, and small environmental contaminants [2].

Table: Comparison of Major ELISA Types

| Feature | Direct ELISA | Indirect ELISA | Sandwich ELISA | Competitive ELISA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Low | High | Highest | Variable |

| Specificity | Moderate | Moderate | High | High for small analytes |

| Complexity | Low (fewer steps) | Medium | High | Medium |

| Time Required | Short | Medium | Long | Medium |

| Antibody Requirements | Labeled Primary | Unlabeled Primary + Labeled Secondary | Matched Antibody Pair | Labeled Antigen/Antibody |

| Primary Application | Antigen detection, immunohistochemistry | Antibody screening (e.g., serology) | Quantifying proteins in complex samples | Measuring small molecules (hormones, drugs) |

Experimental Protocol: Running a Sandwich ELISA

The following detailed protocol outlines the standard workflow for a sandwich ELISA, which is the most commonly used format for quantitative protein analysis.

The flowchart above visualizes the sequential steps of a sandwich ELISA protocol, from plate coating to final signal measurement.

Step-by-Step Protocol

Plate Coating:

- Prepare a solution of the capture antibody (typically 2-10 μg/mL) in a coating buffer such as carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.4) or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) [1].

- Dispense the solution into the wells of a polystyrene microtiter plate (ensure you are using a protein-binding assay plate, not a tissue-culture-treated plate) [1].

- Seal the plate and incubate for several hours at 37°C or overnight at 4°C to allow for passive adsorption of the antibody to the plastic surface [1] [2].

Washing:

- Discard the coating solution by inverting the plate.

- Fill each well with a wash buffer, typically PBS containing a mild non-ionic detergent (e.g., 0.05% Tween 20). The detergent helps to remove weakly adsorbed proteins.

- Repeat the wash process 2-3 times. For automated processing, a microplate washer can be used. Proper and thorough washing is critical for minimizing background signal [2].

Blocking:

- Add a blocking buffer to every well to cover all remaining unsaturated binding sites on the polystyrene surface. Common blocking agents include 1-5% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), casein, or non-fat dry milk [2] [3].

- Incubate the plate for at least 1-2 hours at room temperature [2].

- After incubation, wash the plate as described in Step 2 to remove excess blocking agent.

Sample and Standard Incubation:

- Prepare a serial dilution of a known standard of the target protein to generate a standard curve for quantification.

- Add the diluted standards, controls, and test samples to the designated wells. Always run samples and standards in duplicate or triplicate to ensure statistical reliability [6] [7].

- Cover the plate and incubate for 90 minutes at 37°C or as optimized for the specific assay, allowing the antigen to bind to the capture antibody [2].

- Wash the plate thoroughly to remove any unbound antigen and other sample components.

Detection Antibody Incubation:

- Add the enzyme-conjugated detection antibody to each well. This antibody must be specific to a different epitope on the target antigen than the capture antibody.

- Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature [2].

- Perform another series of washes to remove any unbound detection antibody.

Signal Development and Measurement:

- Prepare the appropriate substrate solution for the enzyme conjugate (e.g., TMB for HRP, pNPP for AP) [2].

- Add the substrate to each well and incubate in the dark for a defined period (usually 15-30 minutes) to allow color or light development.

- Stop the enzymatic reaction by adding a stop solution (e.g., sulfuric acid for TMB, which changes the color from blue to yellow) [2].

- Immediately measure the signal using a microplate reader. The type of reading depends on the detection method: optical density (OD) for colorimetric substrates, fluorescence intensity for fluorescent substrates, or relative light units (RLU) for chemiluminescent substrates [4] [1].

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Accurate data analysis is crucial for transforming the raw signal from an ELISA into meaningful quantitative results. This process involves generating a standard curve and using it to interpolate the concentrations of unknown samples.

Standard Curve and Curve Fitting

The standard curve is the cornerstone of quantitative ELISA. It is created by plotting the mean absorbance (or other signal type) of the serial dilutions of the known standard against their corresponding concentrations [6].

- Curve Fitting Models: The relationship between concentration and signal is often non-linear. Several curve-fitting models can be applied, and the best one should be selected based on which provides the best fit for the data points [6].

- Linear and Log/Log: Simple but often only fit the central, linear portion of the curve, compressing data at the lower end [6].

- Semi-Log: Plots the log of the concentration against the linear signal, often resulting in a sigmoidal curve that distributes data points more evenly [6].

- Four- or Five-Parameter Logistic (4PL/5PL): These are the most sophisticated and recommended models for immunoassays. They account for the upper and lower asymptotes and the inflection point of the sigmoidal curve. The 5PL model also accounts for asymmetry, providing a superior fit for most ELISA data [6].

Table: Quantitative Data Analysis from a Standard Curve

| Standard Concentration | Mean Absorbance (450 nm) | Interpolated Concentration (Back-Calculated) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 pg/mL | 0.050 | (Blank) |

| 31.25 pg/mL | 0.150 | 30.1 pg/mL |

| 62.5 pg/mL | 0.280 | 63.8 pg/mL |

| 125 pg/mL | 0.550 | 122.1 pg/mL |

| 250 pg/mL | 1.100 | 255.3 pg/mL |

| 500 pg/mL | 1.800 | 488.0 pg/mL |

| 1000 pg/mL | 2.200 | 1050.0 pg/mL |

Note: The above table demonstrates how a standard curve is constructed and validated. The "Interpolated Concentration" is derived by treating the standard's OD value as an unknown and reading its concentration from the curve, a process called "back-fitting." A good fit is indicated when the back-calculated values are within +/- 10% of the expected values [7].

Calculating Sample Concentration and Assay Validation

- Interpolation of Unknowns: To determine the concentration of an unknown sample, first calculate the average absorbance of its replicates. Locate this value on the y-axis of the standard curve, draw a horizontal line to the curve, and then a vertical line down to the x-axis to read the corresponding concentration [6] [7]. If the sample was diluted, multiply the interpolated concentration by the dilution factor.

- Assessing Precision: Coefficient of Variation (CV): The precision of replicate measurements is assessed by calculating the CV. The CV is the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean, expressed as a percentage. A CV of ≤20% for duplicates is generally considered acceptable. A higher CV indicates greater inconsistency, potentially caused by pipetting errors, contamination, or temperature fluctuations across the plate [6] [7].

- Assessing Accuracy: Spike-and-Recovery: To determine if the sample matrix (e.g., serum, cell culture media) is interfering with the assay, a spike-and-recovery experiment is performed. A known amount of the target antigen is spiked into the sample matrix and a reference buffer. The recovery percentage is calculated by comparing the measured concentration in the matrix to the concentration in the buffer. Significant deviation from 100% recovery indicates matrix interference, and may require using a matrix-matched standard curve or further sample dilution [6].

Applications in Research and Diagnostics

ELISA's versatility, specificity, and sensitivity have cemented its role as an indispensable tool in both basic research and clinical diagnostics.

Research Applications

In the research laboratory, ELISA serves as a fundamental tool for biological discovery [4]. Key applications include:

- Protein Quantification and Pathway Analysis: Researchers use ELISA to precisely measure the concentration of specific proteins, such as cytokines, chemokines, and signaling proteins, in complex samples like cell lysates or tissue culture supernatants. This allows for the study of cellular signaling pathways and their activation states [4].

- Detection of Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs): Specialized ELISA kits can detect and quantify specific PTMs, such as phosphorylation, acetylation, or ubiquitination, providing insights into the regulatory mechanisms controlling protein function [4].

- Hybridoma Screening and Antibody Characterization: ELISA is the standard method for screening hybridoma cell lines to identify those producing monoclonal antibodies of the desired specificity. It is also used to characterize antibody affinity and specificity [5].

Clinical and Diagnostic Applications

The ELISA platform is a cornerstone of modern clinical diagnostics, enabling the detection of biomarkers for a wide array of diseases [2].

- Infectious Disease Serology: ELISA is widely used to detect patient antibodies against viral, bacterial, and fungal pathogens, aiding in the diagnosis of infections such as HIV, hepatitis A/B/C, and Lyme disease [4] [2].

- Autoimmune Disease Diagnostics: Detection of autoantibodies, such as antinuclear antibodies (ANA), anti-dsDNA, and others, is critical for diagnosing autoimmune disorders like systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [2] [8].

- Cancer and Hormone Biomarker Monitoring: ELISA tests are used to measure tumor markers like Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) and Carcinoembryonic Antigen (CEA) for cancer screening and monitoring [2]. They are also used to quantify hormone levels (e.g., hCG for pregnancy tests, luteinizing hormone, testosterone) for assessing endocrine function [2].

- Therapeutic Drug Monitoring and Toxicology: ELISA can measure the concentration of drugs and their metabolites in patient serum to ensure therapeutic levels are maintained. It is also employed in screening for drugs of abuse [2].

Flow cytometry stands as a powerful analytical technology that enables the detailed characterization of individual cells within a heterogeneous population. The core principle of this technique involves analyzing single cells as they pass in a fluid stream through a laser beam, allowing for simultaneous measurement of multiple physical and chemical properties at rates of thousands of cells per second [9]. This capability for high-throughput, multiparametric analysis at the single-cell level has established flow cytometry as an indispensable tool in biomedical research, clinical diagnostics, and drug development [10].

The fundamental workflow involves three interconnected systems: a fluidics system that transports and focuses cells single file in a stream, an optics system that illuminates cells with lasers and collects resulting light signals, and an electronics system that converts these signals into digital data for analysis [11]. Unlike bulk measurement techniques that provide population averages, flow cytometry preserves cellular heterogeneity, enabling identification of rare cell populations and detailed immunophenotyping that has revolutionized our understanding of complex biological systems [12].

Core Principles and Instrumentation

Fundamental Working Mechanism

The operational principle of flow cytometry centers on the hydrodynamic focusing of cells within a rapidly flowing fluid stream. This process forces cells to pass single-file through one or more focused laser beams, where each cell scatters light and may emit fluorescence from associated dyes or antibodies [11]. The fluidics system creates a laminar flow that precisely positions cells through the center of the laser interrogation point, ensuring consistent illumination and signal detection [13].

As each cell intersects the laser beam, it produces two types of light scattering: forward scatter (FSC), which correlates with cell size, and side scatter (SSC), which provides information about cellular granularity and internal complexity [9]. Simultaneously, if the cell is labeled with fluorescent markers, these fluorochromes absorb light at specific wavelengths and emit light at longer wavelengths, providing quantitative information about specific cellular components or markers [13].

Figure 1: Core Workflow of Flow Cytometry Analysis

Key Instrumentation Components

Modern flow cytometers incorporate sophisticated integrated systems that work in concert to generate high-quality data:

Fluidics System: This critical component manages sample introduction and transport. The system utilizes sheath fluid to create hydrodynamic focusing, precisely aligning cells through the laser interrogation point. This ensures that cells pass through the laser beam individually, preventing clogs and maintaining consistent analysis conditions across all cells in a sample [13].

Optics System: The optics consist of excitation sources (typically multiple lasers emitting at different wavelengths) and light collection pathways. Lasers illuminate cells as they pass through the interrogation point, while sophisticated arrays of lenses, filters (including dichroic mirrors and bandpass filters), and detectors collect the resulting light signals. Advanced systems can measure up to 50 parameters simultaneously, providing comprehensive cellular characterization [10].

Electronics System: This component converts detected light signals into digital data. Photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) or avalanche photodiodes (APDs) detect photons and convert them to electrical signals, which are then digitized by analog-to-digital converters. The electronics system also manages signal amplification and compensation to address spectral overlap between fluorochromes, ensuring accurate multicolor analysis [9] [13].

Key Applications in Research and Drug Development

Immunophenotyping and Disease Research

Flow cytometry serves as the gold standard for immunophenotyping—the identification and characterization of immune cells based on specific surface and intracellular markers. By using antibodies conjugated to fluorescent dyes against cluster of differentiation (CD) markers, researchers can precisely quantify different immune cell populations (T cells, B cells, NK cells, monocytes) and their activation states in peripheral blood, tissues, or culture systems [12]. This application has proven essential for:

- Cancer Diagnostics: Detection and classification of hematological malignancies such as leukemia and lymphoma through aberrant marker expression patterns [14].

- Immunodeficiency Diseases: Monitoring CD4+ T-cell counts in HIV patients to track disease progression and treatment efficacy [15].

- Autoimmune Disorders: Characterizing dysregulated immune cell populations in conditions like rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis [10].

The technology's capacity for multiparametric analysis allows researchers to examine complex immune profiles beyond simple cell counting, providing insights into cellular function, differentiation states, and pathological mechanisms [12].

Drug Discovery and Development

The pharmaceutical industry increasingly relies on flow cytometry throughout the drug development pipeline, from target identification to clinical trials [10]. High-throughput flow cytometry systems capable of processing 384-well plates in automated workflows have dramatically accelerated drug screening [12]. Key applications include:

- Target Validation: Confirming presence of drug targets on specific cell types and quantifying receptor density [16].

- Mechanism of Action Studies: Assessing intracellular signaling pathways, phosphorylation events, and transcriptional changes in response to drug treatment [10].

- Immunotherapy Development: Characterizing CAR-T cells and other engineered cellular therapies by measuring transduction efficiency, proliferation, and functional markers [10].

- Toxicity Assessment: Evaluating drug-induced apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, and mitochondrial membrane potential changes [13].

The technology's single-cell resolution provides crucial information about heterogeneous responses to therapeutic compounds that would be masked in bulk measurements, enabling more informed decisions about candidate selection and dosing [12].

Comparative Analysis with ELISA

While both flow cytometry and ELISA are essential immunochemical methods, they serve distinct purposes and provide complementary information. The table below summarizes their key differences:

Table 1: Comparison Between Flow Cytometry and ELISA

| Parameter | Flow Cytometry | ELISA |

|---|---|---|

| Analysis Level | Single-cell resolution [17] | Population average [17] |

| Sample Type | Cell suspensions [9] | Serum, plasma, supernatants [17] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | High (up to 50 parameters simultaneously) [10] | Limited (typically single analyte) [17] |

| Throughput | Moderate to high (up to thousands of cells/second) [12] | High (96-384 well plates) [17] |

| Data Output | Multidimensional: size, granularity, fluorescence [9] | Unidimensional: concentration [17] |

| Primary Applications | Cell classification, phenotyping, functional assays [14] | Soluble protein quantification [17] |

| Cost Considerations | Higher instrument and reagent costs [15] | Cost-effective for routine screening [17] |

A methodological comparison study examining cytokine measurements (IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α) demonstrated that while regression analysis showed general compatibility between flow cytometry and ELISA, Bland-Altman plots revealed significant differences in measurements for IL-1β and TNF-α, highlighting the importance of selecting the appropriate method based on the specific research question [18].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful flow cytometry experiments require carefully selected reagents optimized for specific applications. The following table outlines essential materials and their functions:

Table 2: Essential Flow Cytometry Reagents and Their Functions

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity Reagents | Fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies [16] | Target specific cellular antigens for immunophenotyping; largest segment of flow cytometry reagents market (38.50% share in 2024) [16] |

| Dyes & Stains | Viability dyes (PI, 7-AAD), DNA binding dyes (DAPI), calcium indicators (Indo-1) [13] | Assess cell viability, apoptosis, cell cycle status, and functional assays; fastest-growing product segment [16] |

| Calibration & Validation Reagents | Compensation beads, calibration beads [16] | Standardize instrument performance, ensure reproducibility and accuracy; essential for quality control [16] |

| Buffers & Media | Staining buffer, fixation buffer, permeabilization buffer [13] | Maintain cell integrity during processing, enable intracellular staining, preserve sample for analysis [13] |

The global flow cytometry reagents market, valued at USD 2,925.75 Million in 2024, reflects the critical importance of these specialized reagents, with projections estimating growth to USD 5,536.69 Million by 2032 at a CAGR of 8.3% [16]. Antibodies constitute the largest product segment, while dyes and stains represent the fastest-growing category, driven by increasing demand for multiplexed panels and high-parameter experiments [16].

Experimental Protocols

Sample Preparation Protocol

Proper sample preparation is critical for obtaining reliable flow cytometry data. The following protocol outlines key steps for preparing peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) for immunophenotyping:

Cell Harvesting and Suspension: Obtain single-cell suspension from blood, tissue, or culture. For solid tissues, enzymatic digestion (collagenase, trypsin) or mechanical dissociation may be required. Filter through 35-70μm mesh to remove clumps and ensure single-cell suspension [13].

Cell Staining:

- Surface Marker Staining: Aliquot 1×10^6 cells per tube. Add Fc receptor block to prevent nonspecific antibody binding. Add titrated antibody cocktails and incubate for 30 minutes in the dark at 4°C [13].

- Viability Staining: Include viability dye (e.g., propidium iodide, 7-AAD) to exclude dead cells from analysis [13].

- Intracellular Staining: For intracellular markers (cytokines, signaling proteins), fix cells with 4% paraformaldehyde, then permeabilize with methanol or saponin-based buffers before antibody staining [13].

Washing and Resuspension: Wash cells twice with cold flow cytometry buffer (PBS + 1% BSA + 0.1% sodium azide) to remove unbound antibody. Resuspend in 300-500μl buffer for acquisition [13].

Controls Setup: Include unstained cells, single-color controls for compensation, fluorescence-minus-one (FMO) controls for gating, and isotype controls for assessing nonspecific binding [13].

Instrument Setup and Quality Control

Proper instrument setup ensures optimal data quality and reproducibility:

Daily Startup and QC: Perform instrument quality control using calibration beads (e.g., CS&T beads) to verify laser alignment, fluidics, and optical detection stability. Document performance metrics [9].

Voltage Optimization: Adjust photomultiplier tube (PMT) voltages to place negative populations on-scale while avoiding signal saturation. Use reference samples to establish consistent voltage settings across experiments [13].

Compensation Setup: Acquire single-color stained controls for each fluorochrome in the panel. Calculate compensation matrices to correct for spectral overlap between detection channels. Apply compensation during acquisition or post-acquisition [13].

Gating Strategy: Establish hierarchical gating approach: (1) FSC-A vs SSC-A to identify cell population of interest, (2) FSC-A vs FSC-H to exclude doublets, (3) viability dye to exclude dead cells, (4) sequential marker gates to identify subpopulations [13].

Figure 2: Hierarchical Gating Strategy for Immunophenotyping

Future Directions and Emerging Applications

Flow cytometry technology continues to evolve with several emerging trends shaping its future applications in research and drug development:

Technological Innovations

High-Parameter Cytometry: Advanced spectral flow cytometers now enable simultaneous measurement of 40+ parameters per cell using full spectrum fingerprinting and sophisticated unmixing algorithms [10]. The Cytek Aurora system exemplifies this capability with its five-laser, 64-detector configuration [9].

High-Throughput Automation: Integrated systems like the ZE5 Cell Analyzer can process 96-well plates in less than 15 minutes and 384-well plates in under one hour, enabling large-scale compound screening and integration with robotic workcells [12].

Imaging Flow Cytometry: Instruments like the ImageStream MKII combine flow cytometry with microscopy, capturing high-resolution images of each cell in flow, enabling spatial analysis of protein localization and cell morphology [9].

Data Analysis and Integration

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: AI algorithms are revolutionizing flow cytometry data analysis through automated population identification, rare event detection, and quality control. These tools help manage the complexity of high-dimensional datasets and reduce operator-dependent variability [10] [15].

Multi-Omics Integration: The combination of flow cytometry with genomic and proteomic approaches provides comprehensive cellular characterization. Mass cytometry (CyTOF) uses metal-conjugated antibodies and time-of-flight detection, dramatically expanding parameter capacity without spectral overlap [10].

The global flow cytometry market reflects these technological advancements, with projections estimating growth from USD 5.71 billion in 2024 to USD 12.11 billion by 2034, driven by increasing applications in drug development, biomarker discovery, and clinical diagnostics [15]. This expansion is particularly pronounced in the Asia-Pacific region, which is expected to register the fastest CAGR of 8.35% from 2025 to 2034, fueled by rapid healthcare infrastructure development and growing biotechnology sectors in China and India [15].

In the realm of immunochemical methods, Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) and Flow Cytometry stand as two foundational techniques that, while sometimes overlapping in application, serve distinct primary purposes. ELISA is predominantly used for the sensitive quantification of soluble molecules, whereas flow cytometry excels at cellular phenotyping and the analysis of cell populations at a single-cell level. Understanding their specific capabilities, optimal applications, and inherent limitations is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals designing robust experimental workflows. This guide provides an in-depth technical comparison of these methodologies, framing them within the context of selecting the right tool for specific research questions in immunology and biomedical science.

Core Principles and Technical Specifications

ELISA: Soluble Molecule Quantification

The Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) is a plate-based assay technique designed for detecting and quantifying soluble substances such as peptides, proteins, antibodies, and hormones in a solution [1] [2]. The core principle relies on the specific binding of an antibody to its target antigen, with detection achieved via an enzyme-linked conjugate that produces a measurable signal, typically a color change, upon substrate addition [19]. The key differentiator of ELISA is that it provides an average concentration of the analyte within the bulk sample, without preserving cellular context [20].

Common ELISA Formats:

- Direct ELISA: Uses a single enzyme-conjugated antibody for direct detection, offering speed but lower signal amplification [2].

- Indirect ELISA: Employs an unlabeled primary antibody and an enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody, providing greater sensitivity through signal amplification [1] [2].

- Sandwich ELISA: Requires two antibodies binding to different epitopes of the target antigen, resulting in high specificity and sensitivity, making it the preferred format for complex samples [1] [19].

- Competitive ELISA: Used for detecting small molecules; the sample antigen competes with a labeled reference antigen for a limited number of antibody-binding sites [1] [2].

Flow Cytometry: Single-Cell Analysis and Phenotyping

Flow cytometry is a laser-based technology that analyzes the physical and chemical characteristics of cells or particles as they flow in a fluid stream through a beam of light [21] [22]. It is a powerful tool for multiparameter analysis, allowing simultaneous measurement of multiple parameters—such as cell size, granularity, and the presence of specific surface or intracellular proteins—for individual cells within a heterogeneous population [20] [22]. This capability to assess thousands of cells per second provides unparalleled insight into cellular heterogeneity.

Advanced Flow Cytometry Modalities:

- Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS): A specialized form of flow cytometry that physically separates cell populations based on their fluorescent or light-scattering properties for downstream analysis [22].

- Intracellular Staining (ICS): Permits the detection of intracellular cytokines, transcription factors, and phospho-proteins (phospho-flow) following cell fixation and permeabilization [22].

- Multiplex Bead Arrays: Utilizes multiple sets of beads with distinct fluorescence intensities to simultaneously quantify multiple soluble analytes in a single sample, akin to a multiplexed ELISA [21] [23].

Comparative Analysis: Application Scope and Data Output

The decision to employ ELISA or flow cytometry hinges on the research question. The table below summarizes the core applications and strengths of each technique.

Table 1: Core Applications and Data Output of ELISA vs. Flow Cytometry

| Feature | ELISA | Flow Cytometry |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Application | Quantification of soluble analytes (e.g., cytokines, hormones, antibodies) [20] [2] | Cellular phenotyping, cell counting, and analysis of cell surface and intracellular markers [21] [22] |

| Sample Type | Serum, plasma, cell culture supernatant, tissue lysates [1] | Single-cell suspensions (e.g., blood, bone marrow, dissociated tissues) [22] |

| Data Output | Average concentration of the analyte in the sample [20] | Multi-parameter data for every individual cell analyzed |

| Key Strength | High sensitivity for quantifying low-abundance soluble molecules; high-throughput; cost-effective for large sample batches [20] | Analysis of cellular heterogeneity and identification of rare cell populations; functional assays (e.g., signaling, apoptosis) |

| Throughput | High (96 or 384-well plate format) [1] | Medium to High (rapid analysis of 30,000+ cells/second, but sample preparation can be time-consuming) [21] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Low (typically single-analyte per well) | High (simultaneous measurement of 10-50+ parameters per cell) [21] |

Decision Framework: Selecting the Appropriate Assay

When to Prioritize ELISA

- Quantifying Secreted Factors: Use ELISA when your goal is to measure the concentration of a specific protein (e.g., a cytokine like IL-6, a hormone like hCG, or a clinical biomarker like PSA) in a biological fluid [2]. For example, assessing vaccine efficacy by measuring anti-Mtb antibody levels in serum is a classic ELISA application [24].

- Large Sample Batch Analysis: When processing hundreds of samples for a single analyte, ELISA's 96- or 384-well plate format and simpler data analysis make it more efficient and cost-effective [20].

- Limited Cell Numbers or Sample Volume: If the sample is a crude lysate or supernatant with limited cell numbers, ELISA is preferable as it does not require a single-cell suspension.

When to Prioritize Flow Cytometry

- Immunophenotyping: Use flow cytometry to identify and characterize different cell types in a heterogeneous mixture. This is indispensable in immunology for profiling immune cells (e.g., T-cell subsets via CD4/CD8 staining) and in hematology for diagnosing and classifying leukemias and lymphomas [21].

- Analyzing Cellular Heterogeneity: When you need to understand the distribution of a marker within a population (e.g., what percentage of cells are positive, and how intensely do they express the protein?), flow cytometry is the only suitable choice [22].

- Complex Functional Studies: For assays that require correlating multiple parameters at a single-cell level—such as intracellular cytokine staining coupled with cell surface marker analysis, phospho-signaling studies, or apoptosis assays—flow cytometry is essential [22].

Table 2: Technical and Practical Considerations for Assay Selection

| Consideration | ELISA | Flow Cytometry |

|---|---|---|

| Budget & Cost | Lower instrument and per-assay cost; cost-effective for large batches [20] | High instrument acquisition and maintenance costs; expensive fluorescent reagents [20] [15] |

| Required Expertise | Straightforward protocol and data analysis; requires standard laboratory skills [20] | Requires significant technical expertise for panel design, instrument operation, and complex data analysis [20] |

| Dynamic Range & Reproducibility | High sensitivity with a broad dynamic range for concentration measurements [23] | Excellent for detecting relative expression levels across cells; highly reproducible for population frequencies [23] |

| Sample Processing | Simple; often requires no special processing beyond centrifugation | Complex; requires a high-quality single-cell suspension; may need cell staining, fixation, and permeabilization [22] |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The success of both ELISA and flow cytometry is critically dependent on the quality of reagents used. The following table outlines the core components required for each technique.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ELISA and Flow Cytometry

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application |

|---|---|---|

| Coated Microplates | 96- or 384-well polystyrene plates that passively bind proteins or antibodies to immobilize the capture reagent [1] [19] | ELISA |

| Matched Antibody Pairs | A set of two antibodies that bind to non-overlapping epitopes on the target antigen, used for capture and detection [1] | Sandwich ELISA |

| Enzyme Conjugates | Reporter enzymes (e.g., Horseradish Peroxidase-HRP, Alkaline Phosphatase-AP) linked to detection antibodies or streptavidin to catalyze signal generation [1] [2] | ELISA |

| Fluorochrome-Conjugated Antibodies | Antibodies tagged with fluorescent dyes (e.g., FITC, PE, APC) to detect specific cell markers. | Flow Cytometry |

| Viability Dyes | Fluorescent dyes (e.g., propidium iodide, LIVE/DEAD fixable stains) that exclude dead cells from analysis to improve data accuracy [22] | Flow Cytometry |

| Cell Stimulation & Fixation/Permeabilization Kits | Chemical agents to activate cellular processes (e.g., PMA/lonomycin) and buffers to fix cells and permeabilize membranes for intracellular staining [22] | Intracellular Flow Cytometry |

| Sheath Fluid | A buffered saline solution that hydrodynamically focuses the sample stream, ensuring single-cell interrogation by the laser [21] [22] | Flow Cytometry |

Experimental Workflow Protocols

Detailed Protocol: Sandwich ELISA

The following diagram outlines the key steps in a standard sandwich ELISA protocol.

Step-by-Step Methodology [19] [2]:

- Coating: Dilute the capture antibody in a carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.4) or PBS (pH 7.4) to a concentration of 2–10 μg/mL. Add 100 μL per well to a 96-well microplate. Seal the plate and incubate for 15-18 hours at 4°C or for 1-2 hours at 37°C.

- Washing and Blocking: Discard the coating solution and wash the plate 3 times with a washing buffer (e.g., PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20). Add 200-300 μL of a blocking buffer (e.g., 1-5% BSA or non-fat dry milk in PBS) to each well. Incubate at 37°C for 1-2 hours to cover any remaining protein-binding sites.

- Sample and Standard Incubation: Wash the plate 3 times. Prepare a serial dilution of your standard for a standard curve. Add 100 μL of standards or diluted samples to appropriate wells. Incubate at 37°C for 1-2 hours.

- Detection Antibody Incubation: Wash the plate 3-5 times. Add 100 μL of the biotinylated or enzyme-conjugated detection antibody (diluted in blocking buffer) to each well. Incubate at 37°C for 1 hour.

- Enzyme Conjugate Incubation (if needed): Wash the plate 3-5 times. If using a biotinylated detection antibody, add 100 μL of streptavidin-HRP (diluted per manufacturer's instructions). Incubate at 37°C for 30-60 minutes.

- Signal Development and Detection: Wash the plate 3-5 times. Add 100 μL of substrate solution (e.g., TMB for HRP) to each well. Incubate in the dark at room temperature for 5-30 minutes until color develops. Stop the reaction by adding 50-100 μL of stop solution (e.g., 1M H₂SO₄ for TMB). Immediately measure the absorbance at the appropriate wavelength (e.g., 450 nm for TMB) using a microplate reader.

Detailed Protocol: Immunophenotyping by Flow Cytometry

The workflow for a typical cell surface immunophenotyping experiment is as follows.

Step-by-Step Methodology [21] [22]:

- Sample Preparation: Isolate cells (e.g., Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) from blood using density gradient centrifugation) and resuspend in a FACS buffer (PBS with 1-2% FBS and 0.1% sodium azide). Filter cells through a 70-μm nylon mesh to obtain a single-cell suspension and remove clumps. Count cells and determine viability.

- Cell Staining (Cell Surface):

- Viability Staining (Optional but Recommended): Resuspend cell pellet in a viability dye (e.g., fixable viability dye) diluted in PBS. Incubate for 15-30 minutes at 4°C in the dark. Wash with FACS buffer.

- Fc Receptor Blocking: Incubate cells with an Fc receptor blocking agent (e.g., human or mouse IgG) for 10-15 minutes at 4°C to reduce non-specific antibody binding.

- Antibody Staining: Prepare a master mix of fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies diluted in FACS buffer. Add the antibody mix to the cell pellet, mix gently, and incubate for 20-30 minutes at 4°C in the dark.

- Washing and Fixation: Wash cells twice with FACS buffer to remove unbound antibody. Resuspend the cell pellet in FACS buffer, often with the addition of 1-4% paraformaldehyde for fixation (optional, stabilizes the sample for later analysis).

- Data Acquisition: Resuspend the final cell pellet in an appropriate volume of FACS buffer for acquisition. Pass the cells through the flow cytometer. Ensure proper instrument performance by running calibration beads before sample acquisition. Collect data for a sufficient number of events (e.g., 10,000 events for the population of interest).

- Data Analysis: Use flow cytometry analysis software (e.g., FlowJo, FCS Express). First, gate on cells based on forward scatter (FSC-A, correlates with size) and side scatter (SSC-A, correlates with granularity) to exclude debris. Then, gate on single cells using FSC-H vs FSC-A to exclude doublets. Finally, apply fluorescent markers to identify and quantify specific cell populations (e.g., CD3+CD4+ T-cells).

ELISA and flow cytometry are not competing techniques but rather complementary pillars of modern biomedical research. ELISA remains the gold standard for the sensitive and quantitative measurement of soluble biomarkers, hormones, and cytokines in a high-throughput manner. In contrast, flow cytometry is the unequivocal choice for the dissection of cellular heterogeneity, immunophenotyping, and complex functional single-cell analyses. The choice between them is not a matter of which is superior, but which is the right tool for the specific biological question at hand. A well-designed research plan, particularly in complex fields like immunology and drug development, will often leverage the unique strengths of both methodologies to build a comprehensive and data-rich understanding of biological systems.

Immunochemical methods such as Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) and flow cytometry form the cornerstone of modern biomedical research and clinical diagnostics. These techniques leverage the specific binding between antigens and antibodies to detect and quantify biological molecules, providing crucial insights into disease mechanisms, immune responses, and therapeutic efficacy. The instrumentation required to perform these analyses ranges from fundamental plate readers to sophisticated cell sorters, each offering distinct capabilities and applications. ELISA operates primarily through plate-based systems where detection occurs via enzymatic reactions, while flow cytometry utilizes laser-based technology to analyze physical and chemical characteristics of cells or particles in suspension [25] [20]. This instrumentation overview examines the core technologies, their operating principles, and their complementary roles in advancing immunology research and drug development.

Understanding the capabilities and limitations of each platform enables researchers to select appropriate methodologies for their specific experimental needs. Plate readers provide high-throughput quantification of soluble analytes, flow cytometers offer multi-parameter analysis at single-cell resolution, and cell sorters add the capability to physically isolate specific populations for downstream applications. Recent technological advancements have further blurred the lines between these platforms, with spectral flow cytometry expanding multiplexing capabilities and integrated systems offering unprecedented analytical power [26] [27]. This guide explores these instruments within the context of ELISA and flow cytometry workflows, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for method selection, experimental design, and data interpretation.

Core Instrumentation Platforms

Plate Readers and ELISA Systems

Plate readers represent the fundamental instrumentation for ELISA methodologies, providing the platform for detecting and quantifying soluble analytes across multiple samples simultaneously. These systems operate by measuring light absorption, fluorescence, or luminescence in microplate formats, typically processing 96 or 384 samples in a single run. The standard ELISA workflow involves immobilizing antigens or antibodies to plate surfaces, applying samples and detection reagents, and finally measuring the signal generated by enzyme-substrate reactions [20]. This process makes plate readers ideal for high-throughput quantification of proteins, antibodies, hormones, and cytokines in various biological matrices including serum, plasma, and cell culture supernatants.

The analytical strength of plate reader-based ELISA systems lies in their robustness, sensitivity, and cost-effectiveness for processing large sample batches. Modern plate readers can detect minute quantities of target molecules, with sensitivities often reaching picogram per milliliter levels, making them sufficiently sensitive for most clinical and research applications [20]. However, a significant limitation of conventional ELISA is its lack of cellular context, as the technique provides bulk measurement of analyte concentrations without information about the cells producing the molecules or their heterogeneity within samples [20]. This constraint has driven the development of more advanced cellular analysis platforms while maintaining ELISA's position as a workhorse technique for quantitative bioanalysis.

Flow Cytometers

Flow cytometers represent a significant technological advancement beyond plate readers, enabling multi-parameter analysis at the single-cell level. These instruments operate on the principle of hydrodynamic focusing, where a single-cell suspension is injected into a stream of fluid and precisely aligned to pass through multiple laser beams at rates of thousands of cells per second [25]. As cells intersect with these lasers, they scatter light and emit fluorescence from labeled antibodies or intrinsic cellular components, generating rich data profiles for each individual event. Detectors then capture this light, converting it into digital signals that can be analyzed to characterize complex cell populations based on size, granularity, and biomarker expression.

Conventional flow cytometers utilize a compensation approach to account for spectral spillover between fluorophore detectors, but this method historically limited the number of parameters that could be simultaneously measured. The emergence of spectral flow cytometry has revolutionized the field by capturing the full emission spectrum of each fluorophore across multiple detectors, then using sophisticated algorithms to "unmix" these overlapping signals [26] [27]. This technological advancement enables researchers to simultaneously analyze dozens of parameters on a single cell, transforming the study of cellular, functional, and phenotypic diversity in immunology research [26]. The increased dimensionality of data generated by spectral flow cytometers has correspondingly driven the development of advanced computational analysis techniques, including dimensionality reduction and clustering algorithms, to extract meaningful biological insights from these complex datasets [26].

Cell Sorters

Cell sorters represent the most advanced category of flow-based instrumentation, combining analytical capabilities with physical cell separation. These systems detect cells of interest based on their light scattering and fluorescence properties, then use sophisticated mechanisms to deflect these cells into collection tubes or plates for downstream applications. The most common sorting technology, electrostatic droplet sorting, involves charging fluid droplets containing target cells as they break from the stream, then deflecting these charged droplets into collection containers using electrostatic fields [27]. This process enables researchers to obtain highly pure populations of specific cell types from heterogeneous mixtures, supporting applications including functional assays, cell line development, and single-cell analysis.

Modern cell sorters have addressed historical challenges including effects on cell viability, long run times, and purity issues through technological innovations. Instruments like the Bigfoot Spectral Cell Sorter can sort a 96-well plate in less than 8 seconds thanks to multi-way plate sorting deflection capability and integrated monitoring systems [27]. The incorporation of spectral unmixing technology into cell sorters has further enhanced their utility, allowing researchers to design more complex panels that identify rare cell populations with greater precision. These advancements make cell sorting an increasingly powerful tool for immunology research, particularly as the field moves toward more sophisticated analyses requiring isolated cell populations for functional studies or -omics applications [27].

Comparative Analysis of Platforms

Technical Specifications and Applications

The selection between plate readers, flow cytometers, and cell sorters depends fundamentally on research objectives, as each platform offers distinct advantages and limitations. ELISA systems with plate readers excel at quantifying soluble analytes in sample supernatants, while flow cytometers provide detailed cellular phenotype information at single-cell resolution, and cell sorters add the capability to isolate specific populations for further study. The following table summarizes the key characteristics, strengths, and limitations of each platform:

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Immunochemical Instrumentation Platforms

| Platform | Key Applications | Key Strengths | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plate Readers (ELISA) | Quantifying soluble proteins, antibodies, hormones; high-throughput screening | Simplicity, robustness, cost-effectiveness for large sample batches, high sensitivity for analyte detection | Lack of cellular context, fixed parameters per assay, limited multiplexing in conventional formats |

| Flow Cytometers | Immunophenotyping, intracellular signaling analysis, cell cycle studies, apoptosis detection | Multi-parameter single-cell analysis, high-throughput cellular profiling, dynamic fluorescence range | Instrument cost and complexity, technical expertise required, data analysis challenges for high-parameter panels |

| Cell Sorters | Isolation of specific cell populations, single-cell cloning, progenitor cell isolation, rare cell population sorting | Combines analysis with physical separation, high purity cell populations, supports downstream functional studies | Higher instrument cost, potential impacts on cell viability and function, longer setup and optimization times |

Methodological Comparison: ELISA vs. Flow Cytometry

The methodological differences between ELISA and flow cytometry extend beyond their instrumentation to encompass their fundamental approaches to biomarker detection. Several studies have directly compared these techniques for specific applications, particularly in cytokine measurement. While regression analysis often shows good correlation between the methods, more sophisticated statistical approaches like Bland-Altman plots reveal more nuanced differences in their agreement [28]. One study comparing IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α measurements found that while both methods showed compatibility for IL-6, they demonstrated dissimilarity for IL-1β and TNF-α measurements when analyzed with Bland-Altman methodology [28].

The emergence of bead-based flow cytometry assays has further expanded the applications of flow cytometry to include soluble analyte detection, traditionally the domain of ELISA. These multiplex assays use fluorescently-coded microspheres as solid supports for capture antibodies, enabling simultaneous quantification of multiple analytes in small sample volumes [29]. Recent innovations have simplified these assays through lyophilization of reagents and one-step detection protocols, reducing operational time from over 3 hours to approximately 1.5 hours while maintaining performance comparable to conventional approaches [30]. This advancement demonstrates how technological improvements continue to enhance the efficiency and accessibility of flow cytometry-based methodologies.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

ELISA Protocol and Validation

The standard ELISA protocol involves multiple critical steps that must be carefully optimized and validated to ensure reliable results. A comprehensive validation process assesses key parameters including precision, accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and robustness [31]. The following workflow outlines the core steps in a sandwich ELISA procedure, which is commonly used for quantitative protein detection:

Table 2: Key Steps in ELISA Validation and Optimization

| Validation Parameter | Assessment Method | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Precision | Intra-assay: multiple replicates on same plate; Inter-assay: replicates across different days | Coefficient of variation (CV) typically <10-15% |

| Accuracy | Spike-and-recovery experiments with known analyte concentrations | Recovery rates of 80-120% generally acceptable |

| Sensitivity | Analysis of standard deviation of blank samples and standard curve slope | Lower limit of detection (LLOD) and quantification (LLOQ) established |

| Specificity | Testing cross-reactivity with related molecules | Minimal interference from structurally similar compounds |

| Linearity | Serial dilutions of samples across assay range | Consistent measured concentrations after accounting for dilution |

Figure 1: ELISA Experimental Workflow. Critical wash steps (red circles) remove unbound reagents between major procedure stages.

Flow Cytometry Staining Protocol

Flow cytometry sample preparation requires meticulous attention to cell viability, antibody titration, and controls to ensure accurate data interpretation. The following protocol outlines the key steps for intracellular staining, which enables detection of cytokines and other internal proteins [25]:

Figure 2: Flow Cytometry Intracellular Staining Workflow. The protocol diverges based on whether researchers are targeting extracellular markers only or both surface and intracellular proteins.

For intracellular targets, fixation is typically performed using 1-4% paraformaldehyde (15-20 minutes on ice) or 90% methanol (10 minutes at -20°C), while permeabilization uses detergents like Triton X-100 (0.1-1%) for nuclear antigens or saponin (0.2-0.5%) for cytoplasmic targets [25]. Centrifugation steps typically occur at 200-300 × g for 5 minutes at 4°C to preserve cell integrity [25]. Recent innovations have simplified these protocols through lyophilized reagent spheres that combine capture beads and detection antibodies, enabling one-step incubation that reduces total assay time from over 3 hours to approximately 1.5 hours while maintaining performance [30].

Advanced Applications and Integration

High-Parameter Analysis and Computational Approaches

The evolution of flow cytometry toward high-parameter analysis has fundamentally transformed data analysis strategies. While traditional flow cytometry data has been analyzed using a hierarchy of two-dimensional plots with manual gating, spectral flow cytometry datasets with dozens of parameters require computational techniques for meaningful interpretation [26]. These approaches include dimensionality reduction methods like t-Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) and Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP), which visualize high-dimensional data in two-dimensional maps while preserving the main data structure [26]. Clustering algorithms such as FlowSOM and PhenoGraph automatically identify cell populations based on marker expression patterns, reducing subjectivity and uncovering populations that might be overlooked through manual analysis [26].

The integration of machine learning with flow cytometry data continues to advance the field's analytical capabilities. Supervised learning approaches including logistic regression, random forest, and support vector machines can predict clinical outcomes or disease severity based on complex cytokine profiles or immunophenotyping data [30]. For example, researchers have used these models to predict HBV viral load or COVID-19 severity using cytokine panels, demonstrating the clinical utility of these computational integrations [30]. The application of unsupervised learning techniques further enables biomarker discovery and patient stratification without prior hypotheses, accelerating the identification of novel biological insights from high-dimensional datasets.

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

The ongoing innovation in immunochemical instrumentation focuses on increasing multiplexing capacity, improving accessibility, and enhancing integration between platforms. Spectral flow cytometry represents one major advancement, with systems now capable of detecting up to 60 parameters simultaneously by analyzing full emission spectra rather than relying on traditional compensation approaches [27]. The development of simplified, lyophilized reagent formats addresses cold chain requirements and enhances assay robustness, potentially expanding access to flow cytometry-based testing in resource-limited settings [30]. Integrated systems that combine cell sorting with downstream molecular analysis, such as single-cell sequencing, further bridge the gap between protein-level and gene-level analyses.

The convergence of ELISA and flow cytometry technologies continues through advanced bead-based platforms that offer the multiplexing advantages of flow cytometry with the operational simplicity approaching traditional ELISA. These systems use fluorescently barcoded beads of varying sizes and fluorescence intensities to simultaneously detect multiple analytes in single samples, significantly increasing throughput while conserving precious clinical specimens [29]. One recently developed assay enables simultaneous measurement of IgM, IgG, and IgA antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 across 624 samples within 2 hours, demonstrating the powerful throughput capabilities of these integrated approaches [29]. As these technologies continue to evolve, they promise to further blur the traditional boundaries between plate-based and flow-based immunochemical methods.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of ELISA and flow cytometry methodologies depends on carefully selected reagents and materials optimized for each platform. The following table details key reagent solutions and their specific functions in experimental workflows:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Immunochemical Methods

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Functions and Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Capture & Detection Antibodies | Primary antibodies, secondary antibody conjugates | Specific antigen recognition; signal amplification through enzyme or fluorophore conjugation |

| Cell Staining Reagents | Viability dyes (7-AAD, DAPI), fixation buffers (1-4% PFA), permeabilization detergents (Triton X-100, saponin) | Live/dead cell discrimination; cellular structure preservation; intracellular antigen access |

| Signal Detection Systems | Enzyme substrates (TMB, ABTS), fluorophore-conjugated antibodies (PE, APC, FITC) | Signal generation through colorimetric, fluorescent, or chemiluminescent detection |

| Assay Buffers and Solutions | Coating buffers, blocking buffers (BSA, serum), wash buffers (PBS with Tween-20) | Optimal antibody binding; reduction of non-specific binding; removal of unbound reagents |

| Bead-Based Multiplexing Systems | Fluorescently-coded microspheres, carboxylated beads for protein coupling | Multiplex analyte detection; high-throughput screening; minimal sample volume requirements |

The instrumentation landscape for immunochemical methods encompasses complementary technologies that address distinct research needs. Plate readers serving ELISA methodologies provide robust, cost-effective solutions for soluble analyte quantification, while flow cytometers enable deep cellular profiling at single-cell resolution. Cell sorters extend these analytical capabilities to include physical separation of target populations for downstream functional studies. The ongoing technological innovations in spectral analysis, computational methods, and reagent engineering continue to expand the applications and accessibility of these platforms. Researchers can leverage this instrumentation overview to make informed decisions about method selection, experimental design, and data interpretation within the broader context of their immunology research objectives and resource constraints. As these technologies continue to converge and evolve, they promise to further enhance our understanding of immune function and accelerate the development of novel therapeutic interventions.

Understanding Light Scatter and Fluorescence in Flow Cytometric Analysis

Flow cytometry is a laser-based technology that provides rapid multi-parametric analysis of single cells in solution as they flow past single or multiple lasers [32]. This technique enables researchers to simultaneously measure both physical and chemical characteristics of a population of cells or particles, making it indispensable in modern immunology, molecular biology, and drug development research [33]. The core principle involves illuminating individual cells with laser light and detecting the resulting light scatter patterns and fluorescence emissions that provide rich information about cellular properties.

When integrated into a broader research strategy involving immunochemical methods like ELISA, flow cytometry offers complementary single-cell resolution that bulk measurement techniques cannot provide. While ELISA excels at quantifying soluble proteins in sample supernatants, flow cytometry reveals cellular heterogeneity and identifies rare cell populations within complex mixtures [20] [17]. This technical guide explores the fundamental principles of light scatter and fluorescence detection in flow cytometry, providing researchers with the knowledge needed to design, execute, and interpret robust flow cytometric assays.

Fundamental Principles of Light Scatter

Light Scatter Measurements

As cells pass through the laser beam in a flow cytometer, they interact with the laser light, causing the light to scatter in various directions. This phenomenon of light scattering provides two primary types of structural information about each cell without requiring any fluorescent labels [32] [34].

Forward Scatter (FSC): FSC measures light that is scattered along the same axis as the laser beam, approximately 0.5-10 degrees from the laser's path. This parameter primarily correlates with cell size and volume, as larger cells cause more light to be scattered in the forward direction. The measurement is typically detected by a photodiode positioned in front of the laser intercept [32] [33].

Side Scatter (SSC): SSC measures light that is scattered at approximately 90 degrees to the laser beam. This parameter indicates cellular granularity and internal complexity, as light is refracted and reflected by internal structures such as granules, nucleus, and organelles. Cells with more complex internal structures will produce higher SSC signals. SSC is collected by lenses positioned perpendicular to the laser path and is detected by photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) for enhanced sensitivity [32] [34].

The combination of FSC and SSC measurements allows researchers to distinguish between major cell populations in a heterogeneous sample, such as blood, where lymphocytes, monocytes, and granulocytes each exhibit distinctive light scattering signatures [35].

Figure 1: Light Scatter Detection in Flow Cytometry

Data Visualization of Light Scatter

Light scatter data is typically visualized using density plots or dot plots that display FSC versus SSC, with each dot representing an individual cell event [35]. These plots enable researchers to identify distinct cell populations based on their physical characteristics and establish electronic "gates" around populations of interest for further fluorescence analysis.

Principles of Fluorescence Detection

Fluorescence in Flow Cytometry

While light scatter provides structural information, fluorescence detection enables the measurement of specific molecular markers on or within cells. Fluorescence analysis requires cells to be labeled with fluorochrome-conjugated reagents that emit light at specific wavelengths when excited by the laser [32].

The fluorescence process involves three key stages:

Excitation: When a fluorochrome-conjugated antibody or dye attached to a cellular component (e.g., surface protein, DNA) passes through the laser beam, it absorbs light energy at a specific wavelength, elevating electrons to an excited state [34].

Emission: As the excited electrons return to their ground state, they release energy in the form of photons of longer wavelength (lower energy) than the excitation light. This emitted light constitutes the fluorescence signal [32] [33].

Detection: The emitted fluorescence is collected by lenses and directed through a series of optical filters to specific detectors (typically PMTs or avalanche photodiodes). Dichroic filters steer fluorescent light to specific detectors, while bandpass filters determine the precise wavelengths of light that reach each detector, allowing measurement of specific fluorochromes [32].

Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS)

A specialized application of flow cytometry is Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS), which physically separates cells based on their light scattering and fluorescence characteristics [33]. In FACS, the stream containing cells is broken into droplets, and droplets containing cells with desired characteristics are electrically charged and deflected into collection tubes using electrostatic deflection plates [32] [33].

Instrumentation and Detection Systems

Flow Cytometer Components

Traditional flow cytometers consist of three integrated systems that work together to analyze cells [32] [34] [33]:

Fluidics System: This system consists of sheath fluid (typically buffered saline) that is pressurized to hydrodynamically focus the sample core, ensuring that cells pass through the laser intercept in single file. Precise fluidic control is essential for consistent illumination and measurement.

Optical System: The optical system includes excitation sources (lasers of various wavelengths) and collection optics (lenses, filters, and detectors). Modern flow cytometers commonly feature multiple lasers (e.g., 405nm violet, 488nm blue, 640nm red) to excite different fluorochromes simultaneously. The collection optics include dichroic mirrors that reflect or transmit specific wavelengths and bandpass filters that isolate narrow wavelength ranges for specific detectors.

Electronics System: This system converts the analog light signals detected by the PMTs into digital signals that can be processed by computer software. The electronic components also control the sorting mechanisms in cell sorters and manage the timing correlations between different measurements on the same cell.

Advanced Cytometry Platforms

Recent technological advances have led to specialized cytometry platforms [32]:

Spectral Analyzers: These instruments measure the entire emission spectrum of each fluorochrome to create a "spectral fingerprint," then computationally "unmix" these signals during analysis. This approach reduces the need for compensation and enables more parameters to be measured simultaneously.

Mass Cytometers (CyTOF): These systems replace fluorescent tags with heavy metal ion-tagged antibodies and detect cells using time-of-flight mass spectrometry. This eliminates spectral overlap issues but does not allow for cell sorting.

Imaging Cytometers: These instruments combine flow cytometry with fluorescence microscopy, capturing images of individual cells as they flow through the system, allowing for subcellular localization studies.

Table 1: Common Lasers and Their Applications in Flow Cytometry

| Laser Wavelength | Common Name | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|

| 355 nm | Ultraviolet (UV) | DNA content analysis, calcium flux studies |

| 405 nm | Violet | Vital dyes, fluorescent proteins (CFP, mCerulean) |

| 488 nm | Blue | FITC, PE, GFP, cell viability, side scatter |

| 532 nm | Green | PE dye analogs, some fluorescent proteins |

| 561 nm | Green-Yellow | PE, PI, mOrange, mCherry |

| 640 nm | Red | APC, Cy5, Alexa Fluor 647 |

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful flow cytometry experiments depend on appropriate fluorochrome-conjugated reagents and controls [32] [17]. The key reagents include:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Flow Cytometry

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorochrome-Conjugated Antibodies | CD3-FITC, CD4-APC, CD8-PE | Detection of specific cell surface or intracellular markers |

| Viability Dyes | Propidium Iodide, 7-AAD | Exclusion of dead cells from analysis |

| DNA Binding Dyes | DAPI, Hoechst 33342 | Cell cycle analysis, DNA content measurement |

| Ion Indicator Dyes | Indo-1, Fluo-3 | Measurement of calcium flux and ion concentrations |

| Fluorescent Proteins | GFP, mCherry, mOrange | Reporter gene expression, transfection efficiency |

When designing multi-color flow cytometry panels, careful consideration must be given to fluorochrome brightness, antigen density, and spectral overlap to ensure optimal resolution of all parameters [33]. Antibody titration experiments are essential to determine the optimal concentration for staining while minimizing background signal [34].

Experimental Protocol for Cell Surface Staining

The following protocol provides a standardized methodology for the detection of cell surface antigens using fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies, a fundamental application in immunophenotyping studies [32] [35]:

Sample Preparation