IHC vs Immunofluorescence: A Guide to Sensitivity, Applications, and Choosing the Right Method

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and Immunofluorescence (IF) for researchers and drug development professionals.

IHC vs Immunofluorescence: A Guide to Sensitivity, Applications, and Choosing the Right Method

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and Immunofluorescence (IF) for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles, detection methods (chromogenic vs. fluorescent), and inherent sensitivities of each technique. The scope extends to methodological applications in diagnostics and complex research, best practices for troubleshooting and optimization, and guidelines for validation and method selection. The integration of digital pathology and AI is also discussed, offering a complete resource for leveraging these powerful spatial biology tools.

Core Principles: How IHC and IF Work from Antibodies to Detection

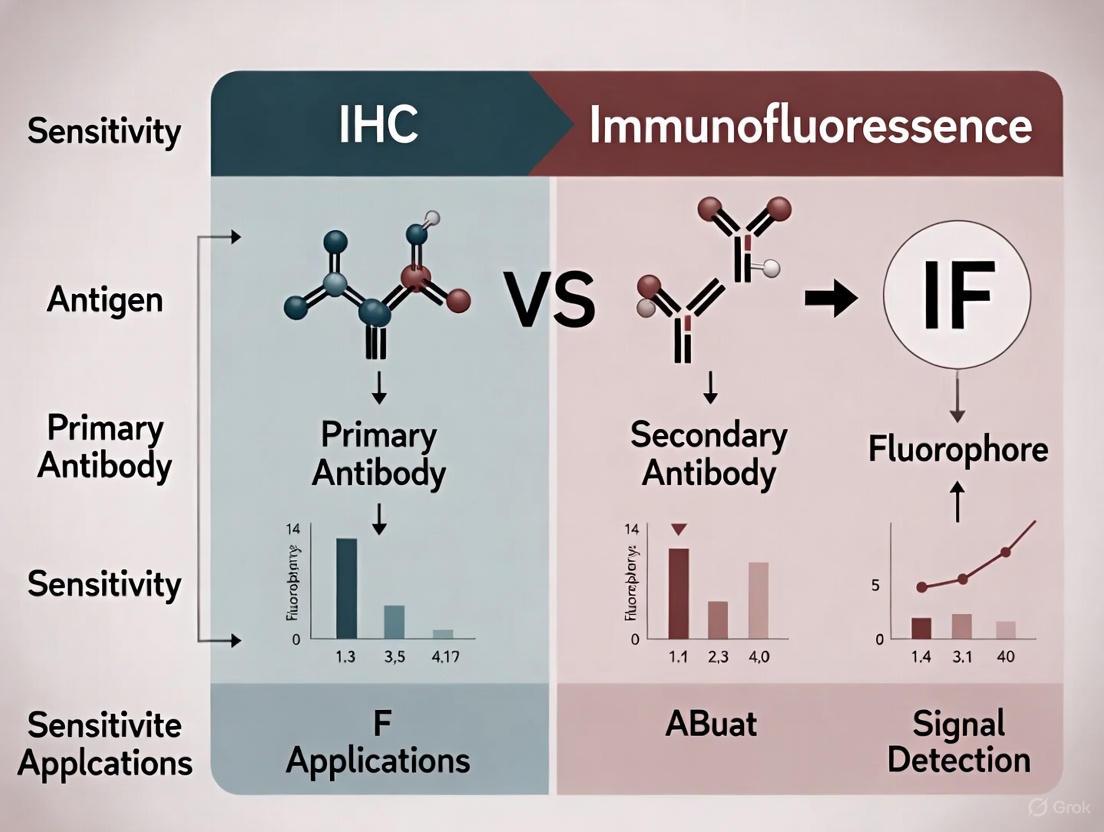

The precise localization and analysis of specific proteins within tissues are fundamental to advancing our understanding of cellular functions, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic development. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate technique for visualizing these targets is a critical decision that directly impacts data quality and interpretability. Two of the most pivotal technologies in this domain are Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and Immunofluorescence (IF). IHC uses enzymatic reactions to produce a permanent, precipitating color signal visible by standard light microscopy, while IF utilizes fluorophore-conjugated antibodies to emit light upon excitation, requiring fluorescence microscopy [1] [2]. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of IHC and IF, focusing on their sensitivity, applications, and performance within modern research and diagnostic contexts. The evolution of these techniques, particularly into multiplexed assays, is reshaping biomarker discovery and validation, offering unprecedented insights into the tumor microenvironment and complex disease states [3] [4].

Fundamental Principles and Key Differences

At their core, both IHC and IF rely on the specific binding of an antibody to a target antigen within a tissue sample. However, their detection methodologies and the resulting data diverge significantly. The foundational difference lies in the label and detection system.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) typically uses enzymes such as Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) or Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) conjugated to an antibody. When a substrate is added, the enzyme catalyzes a reaction that produces an insoluble, colored precipitate at the antigen site [5]. The most common chromogens are 3,3'-Diaminobenzidine (DAB), which produces a brown stain, and compounds that produce a red stain. This stained sample can be viewed with a standard light microscope and produces a permanent slide [1] [5].

Immunofluorescence (IF) employs fluorophores—chemical compounds that re-emit light upon excitation. These fluorophores are conjugated to antibodies, and when excited by light of a specific wavelength, they emit light of a longer wavelength, which is captured using a fluorescence microscope [2] [6]. Common fluorophores include Fluorescein Isothiocyanate (FITC) and Tetramethylrhodamine Isothiocyanate (TRITC) [2].

The table below summarizes the core technical distinctions:

Table 1: Core Technical Principles of IHC and IF

| Feature | Immunohistochemistry (IHC) | Immunofluorescence (IF) |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Enzymatic (Chromogenic) | Optical (Fluorescence) |

| Label Type | Enzyme (e.g., HRP, AP) | Fluorophore (e.g., FITC, TRITC) |

| Signal Output | Colored precipitate | Light emission |

| Microscopy Required | Bright-field/Light microscope | Fluorescence/Confocal microscope |

| Permanence of Signal | Permanent; resistant to fading | Temporary; susceptible to photobleaching |

| Primary Application Context | Diagnostic pathology, clinical diagnostics | Research, cell biology, multiplexing |

A critical advancement for both techniques, particularly for IHC, is antigen retrieval. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues, the most common clinical specimen type, undergo protein cross-linking during fixation that can mask target antigens. To restore antibody binding, two main retrieval methods are employed: Heat-Induced Epitope Retrieval (HIER), which uses heat and buffer to break cross-links, and Protease-Induced Epitope Retrieval (PIER), which uses enzymatic digestion [1] [2]. The choice of method must be optimized for each specific antigen-antibody pair.

Comparative Performance and Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity—the ability to detect low-abundance antigens—is a paramount consideration in technique selection. The inherent signal amplification mechanisms of IHC and IF differ, leading to distinct performance profiles.

IHC Sensitivity: The indirect IHC method, where a labeled secondary antibody binds to a primary antibody, provides the first level of amplification. Modern detection systems further enhance this through polymer-based conjugates, where multiple enzyme molecules are linked to a single antibody, dramatically increasing the number of chromogen molecules deposited per primary antibody [5]. While highly sensitive for many targets, IHC can be limited by enzyme kinetics and the precipitation reaction.

IF Sensitivity: Indirect IF also offers signal amplification, as multiple secondary antibodies can bind to a single primary. Its sensitivity can be vastly increased using methods like the Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA) system. TSA uses the enzyme HRP to catalyze the deposition of numerous fluorophore-labeled tyramide molecules at the antigen site, resulting in a very strong signal that is capable of detecting even low-abundance targets with high clarity [3] [4]. However, IF sensitivity can be compromised by photobleaching, the fading of fluorescence upon prolonged light exposure, which requires the use of anti-fade mounting media [2] [6].

The table below summarizes key performance metrics based on experimental and application data:

Table 2: Performance and Sensitivity Comparison

| Parameter | Immunohistochemistry (IHC) | Immunofluorescence (IF) |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | High (amplified by polymer systems) | Very High (especially with TSA amplification) |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Can be affected by endogenous enzyme activity [5] | Can be affected by tissue autofluorescence |

| Spatial Resolution | Good for cellular and subcellular localization | Excellent; enables super-resolution microscopy |

| Multiplexing Capability | Limited (typically 2-3 markers with different chromogens) | High (5-8+ markers with TSA; 30-60+ with cyclical staining) [3] |

| Quantification Ease | Moderate (color deconvolution required) [3] | High (direct spectral separation per channel) [3] |

| Throughput for Routine Diagnostics | High (compatible with automated stainers) [5] | Lower (requires specialized imaging and analysis) |

Supporting experimental data comes from a 2025 prospective cohort study comparing commercial and in-house assays for detecting neuronal autoantibodies. This study demonstrated that in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), both IFA (Immunofluorescence Assay) and CBA (Cell-Based Assay, often using IF) showed high concordance for key biomarkers. For instance, all samples positive for anti-LGI1 and anti-CASPR2 autoantibodies were successfully detected by both tissue-based IFA and CBA methods, highlighting the robustness of well-validated assays regardless of the core technology [7].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

A successful experiment depends on a rigorously optimized protocol. While IHC and IF share many preliminary steps, their staining and detection phases differ.

Shared Foundational Steps

- Sample Preparation: Tissues are collected and fixed, most commonly in neutral-buffered formalin, to preserve morphology and prevent degradation. For long-term storage and thin sectioning, tissues are embedded in paraffin (FFPE) or frozen in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound [1] [5].

- Sectioning and Mounting: Thin sections (4-5 µm for FFPE) are cut using a microtome (FFPE) or cryostat (frozen) and mounted on glass slides, preferably charged or adhesive-coated to prevent tissue loss [5].

- Deparaffinization and Rehydration: For FFPE sections, paraffin is removed with xylene or xylene-substitutes, followed by a series of ethanol washes to rehydrate the tissue [1].

- Antigen Retrieval: As described in Section 2, HIER or PIER is performed to unmask epitopes [1] [2].

- Blocking: To minimize non-specific background staining, tissues are incubated with a blocking solution. This can be a protein solution like Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), normal serum from the host species of the secondary antibody, or commercial blocking buffers [2] [6]. For IHC, an additional step to block endogenous peroxidase or phosphatase activity is critical [5].

Staining and Detection Protocols

IHC Staining Protocol (Indirect Method with Polymer Detection) [1] [5]:

- Apply primary antibody, optimized for specific dilution and incubation time (e.g., 30-60 minutes at room temperature).

- Wash slides to remove unbound antibody.

- Apply a polymer-conjugated secondary antibody linked to HRP. The polymer technology allows for multiple enzyme molecules per antibody, enhancing sensitivity.

- Wash slides.

- Apply chromogen substrate (e.g., DAB). The enzymatic reaction produces a visible, insoluble precipitate.

- Counterstain with hematoxylin to provide nuclear detail and tissue context.

- Dehydrate, clear, and mount with a permanent mounting medium.

IF Staining Protocol (Indirect Method) [2] [6]:

- Permeabilization: For intracellular targets, a detergent like Triton X-100 is applied post-fixation to allow antibody penetration. (Note: Methanol fixation inherently permeabilizes cells).

- Apply primary antibody (as optimized).

- Wash slides.

- Apply fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody. The incubation must be performed in the dark to prevent photobleaching.

- Wash slides thoroughly in the dark to reduce background.

- Counterstain with a nuclear dye like DAPI.

- Mount with an aqueous, anti-fade mounting medium to preserve fluorescence.

Figure 1: Comparative workflow for IHC and IF staining. While initial sample preparation is shared, detection paths diverge after the blocking step. HIER: Heat-Induced Epitope Retrieval; PIER: Protease-Induced Epitope Retrieval.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The reliability of IHC and IF data is contingent on the quality and appropriate use of key reagents. The following table details essential components for a successful experiment.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for IHC and IF Experiments

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Fixatives (Formalin, Methanol) | Preserves tissue architecture and immobilizes antigens. | Formalin cross-links; Methanol precipitates. Over-fixation can mask epitopes [1] [2]. |

| Primary Antibody | Binds specifically to the target antigen. | Monoclonal (high specificity) vs. Polyclonal (high sensitivity). Validation for specific application (IHC/IF) is critical [5] [6]. |

| Detection System (IHC) | Enzyme-linked polymer conjugates for signal generation. | HRP-polymer systems are common. Blocking of endogenous peroxidase is required [5]. |

| Fluorophore (IF) | Emits light upon excitation for detection. | Brightness, photostability, and spectral overlap must be considered. FITC (green) and TRITC (red) are classics [2]. |

| Chromogen (IHC) | Enzyme substrate that produces a colored precipitate. | DAB (brown) is most common; AP-Red is used for double-staining or melanin-rich tissues [5]. |

| Mounting Medium | Preserves sample and prepares for microscopy. | IF requires anti-fade medium to retard photobleaching [6]. |

| Antigen Retrieval Buffer | Unmasks epitopes obscured by fixation. | Citrate (pH 6.0) and EDTA/ Tris (pH 9.0) are common; optimal pH is antigen-dependent [1] [2]. |

Applications in Research and Drug Development

The choice between IHC and IF is often dictated by the application's primary goal, moving from routine single-analyte detection to complex spatial phenotyping.

Diagnostic and Clinical Applications: IHC is the undisputed gold standard in clinical pathology for tumor classification, subtyping, and biomarker assessment (e.g., PD-L1, HER2) due to its compatibility with bright-field microscopy, permanent record, and resemblance to H&E morphology [8] [5]. IF is primarily a research tool but has critical diagnostic niches, such as detecting autoantibodies in autoimmune diseases like autoimmune encephalitis using tissue-based immunofluorescence assays (IFA) [7].

Drug Development and Biomarker Discovery: IHC is routinely used in preclinical and clinical trials to demonstrate drug efficacy by showing target engagement or downstream pharmacological effects (e.g., down-regulation of a phospho-protein) [1] [8]. The integration of digital pathology and artificial intelligence (AI) is revolutionizing IHC, enabling automated quantification of biomarker expression and minimizing interpretive variability [9] [8].

Multiplexing and Spatial Biology: This is where IF, particularly multiplex Immunofluorescence (mIF), excels. mIF allows for the simultaneous detection of 5-8 (or more) markers on a single tissue section, enabling the detailed characterization of complex cellular interactions and functional states within the tumor microenvironment (TME) [3]. Technologies like Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA) and DNA-barcoded antibodies are at the forefront of this revolution, allowing for high-plex imaging on automated platforms [3] [4]. These spatial biology approaches are generating high-dimensional data that are crucial for identifying novel predictive biomarkers for immunotherapy, such as the density and location of specific T-cell populations [3].

Figure 2: Technique selection guide based on primary application goal. IHC dominates clinical and high-throughput quantitative applications, while IF is preferred for high-resolution and complex multiplexing studies.

IHC and IF are powerful, complementary techniques for protein localization. The decision between them is not a matter of which is universally superior, but which is optimally suited to the specific research or diagnostic question.

IHC remains the cornerstone of diagnostic pathology and is ideal for high-throughput, single-plex biomarker analysis where a permanent record and compatibility with routine laboratory infrastructure are required. Its ongoing integration with digital pathology and AI is enhancing its quantitative power and reproducibility.

IF, particularly in its multiplexed form (mIF), is an indispensable research tool for dissecting complex cellular ecosystems and spatial relationships. Its superior sensitivity and multiplexing capacity make it the technology of choice for advanced biomarker discovery and mechanistic studies in immunology and oncology.

The future of both techniques lies in continued standardization, as championed by organizations like the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer [3], and the deeper integration of automated, high-plex workflows with sophisticated computational analysis. This synergy will undoubtedly unlock deeper biological insights and accelerate the development of novel therapeutics.

The division between Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and Immunofluorescence (IF) represents a fundamental methodological choice in biomedical research and diagnostics, centered on their distinct detection systems. IHC uses chromogenic enzymes to produce permanent, visible stains under brightfield microscopy, while IF employs fluorescent dyes that emit light upon excitation with specific wavelengths [10] [11]. This distinction in detection chemistry creates a cascade of technical differences that dictate their applications, capabilities, and limitations.

The historical development of these techniques reveals their complementary nature. The foundational work began in the 1940s when Albert Coons developed the first fluorescently conjugated antibody, a fluorescein-labeled anti-pneumococcal antibody that could detect bacteria within macrophages [11]. This pioneering work established the basis for IF. The subsequent development of enzyme-conjugated antibodies in the 1960s, particularly with peroxidase and alkaline phosphatase, paved the way for modern IHC, with technical optimizations such as antigen retrieval methods emerging throughout the 1970s and 1980s [11]. Today, both techniques remain indispensable, with IHC dominating clinical diagnostic workflows and IF enabling advanced multiplexing and spatial biology studies.

The core detection principles create this divide. In IHC, antibodies are conjugated to enzymes like Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) or Alkaline Phosphatase (AP). These enzymes catalyze reactions with chromogenic substrates such as 3,3'-Diaminobenzidine (DAB) to form insoluble, colored precipitates at the antigen site [12] [10]. In contrast, IF uses fluorophores - molecules that absorb light at specific wavelengths and emit it at longer wavelengths - directly conjugated to antibodies or detected via fluorescent secondary antibodies [13] [11]. This fundamental difference in detection mechanism creates the performance and application divergence explored in this guide.

Figure 1: Fundamental Detection Principles of IHC and IF. IHC relies on enzyme-mediated chromogenic precipitation, while IF depends on fluorophore excitation and emission properties.

Technical Comparison: Detection Chemistry and Performance

Core Detection Mechanisms

The chromogenic detection system in IHC creates permanent stains through enzymatic amplification. When the enzyme-conjugated antibody binds to its target, it catalyzes the conversion of a colorless chromogenic substrate into a colored, insoluble precipitate that deposits at the antigen site [12] [11]. The most common system uses HRP with DAB, producing a brown precipitate that is easily visible under standard brightfield microscopy. This signal remains stable for years, making IHC ideal for archival purposes and clinical diagnostics requiring long-term sample preservation [10].

In contrast, IF detection relies on the photophysical properties of fluorophores. When a fluorophore absorbs photons at its excitation wavelength, electrons jump to a higher energy state; as they return to ground state, they emit photons at a longer wavelength (lower energy) [13]. This Stokes shift between excitation and emission wavelengths allows separation of signals using optical filters. However, this fluorescence is susceptible to photobleaching when fluorophores permanently lose their ability to fluoresce after prolonged light exposure [13] [10]. The signal stability difference represents a key trade-off: IHC provides permanent archives while IF offers greater sensitivity and multiplexing capability.

Performance Metrics and Limitations

Table 1: Direct Comparison of IHC and IF Performance Characteristics

| Parameter | Immunohistochemistry (IHC) | Immunofluorescence (IF) | Ultra-high-plex IF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Chemistry | Chromogenic enzymes (HRP/AP + DAB, AEC) | Direct or secondary fluorophores | Repeated dye cycles with color separation software |

| Maximum Markers/Slide | 1-2 markers | 2-8 markers | 10-60 markers [10] [3] |

| Signal Stability | Permanent, archivable for years | Moderate (photobleaching risk) | Moderate (software-corrected) |

| Sensitivity/Dynamic Range | Moderate | High | Very high |

| Spatial Resolution | Good (crisp morphology aids pathologist review) | Excellent (subcellular precision) | Excellent (single-cell resolution) |

| Equipment Needed | Brightfield microscope | Fluorescence microscope | Advanced scanner + AI analytics [10] |

| Typical Turnaround Time | 3-5 days | 5-7 days | 7-10 days [10] |

| Best Applications | Diagnostic workflows, GLP archiving, morphology assessment | Spatial biology, co-localization, immune cell typing | Tumor microenvironment, complex immunophenotyping [10] [3] |

The sensitivity advantage of IF stems from the direct relationship between light emission and detector sensitivity, unlike IHC's enzymatic amplification which has a ceiling effect [10]. However, IHC provides superior morphological context that pathologists are trained to interpret, as the chromogenic stain can be easily correlated with tissue architecture in a manner similar to conventional H&E staining [10]. This makes IHC particularly valuable for diagnostic applications where tissue morphology is crucial for interpretation.

A significant limitation of traditional IHC is its restricted multiplexing capability. While attempting to detect multiple markers simultaneously, color overlap complicates analysis, typically limiting standard IHC to 1-2 markers per slide [10]. In contrast, IF's spectral separation enables detection of multiple targets through careful fluorophore selection, with traditional IF handling 2-8 markers and advanced platforms like Akoya PhenoCycler-Fusion reaching 10-60 markers on a single slide [10] [3].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard IHC Protocol for Single-Marker Detection

The following protocol represents a standardized approach for chromogenic IHC, optimized for formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues [11]:

Tissue Preparation and Sectioning: Cut FFPE tissue sections at 4μm thickness using a microtome and mount on charged slides. Bake slides at 60°C for 30 minutes to enhance adhesion.

Deparaffinization and Rehydration: Immerse slides in xylene (2 changes, 10 minutes each), followed by graded ethanol series (100%, 95%, 70% - 2 minutes each), and finally distilled water.

Antigen Retrieval: Perform heat-induced epitope retrieval using citrate buffer (pH 6.0) or Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 9.0) in a pressure cooker or water bath at 90-95°C for 20 minutes. The choice of buffer depends on the antibody epitope characteristics.

Peroxidase Blocking: Incubate with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 minutes to quench endogenous peroxidase activity.

Protein Blocking: Apply serum-free protein block for 10 minutes to reduce non-specific background staining.

Primary Antibody Incubation: Apply optimized primary antibody dilution and incubate for 60 minutes at room temperature or overnight at 4°C.

Secondary Antibody incubation: Apply enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody (typically HRP-polymer systems) for 30 minutes.

Chromogen Development: Incubate with DAB substrate for 3-5 minutes, monitoring development under microscope. Rinse with distilled water to stop reaction.

Counterstaining and Mounting: Counterstain with hematoxylin for 30-60 seconds, dehydrate through graded alcohols and xylene, and mount with permanent mounting medium.

This protocol produces stable, permanent staining suitable for brightfield microscopy and long-term archiving. Validation should include appropriate positive and negative controls to ensure antibody specificity [14].

Standard IF Protocol for Multiplex Detection

The following protocol outlines a standardized approach for multiplex IF, optimized for FFPE tissues [10] [3]:

Tissue Preparation and Sectioning: Cut FFPE tissue sections at 5-7μm thickness and mount on charged slides. The slightly thicker sections compared to IHC help preserve tissue during multiple staining cycles.

Deparaffinization and Rehydration: Same as IHC protocol through xylene and graded ethanol series to distilled water.

Antigen Retrieval: Perform heat-induced epitope retrieval using citrate buffer (pH 6.0) in a pressure cooker at 125°C for 3 minutes, then cool to 90°C.

Autofluorescence Reduction: Optional step using TrueBlack Lipofuscin Autofluorescence Quencher or similar reagent for 30 seconds to reduce background.

Protein Blocking: Apply protein block containing 5% normal serum and 1% BSA for 30 minutes to reduce non-specific binding.

Primary Antibody Incubation: Apply first primary antibody and incubate for 60 minutes at room temperature or overnight at 4°C.

Fluorophore-Conjugated Secondary Antibody: Apply species-specific fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody for 60 minutes at room temperature, protected from light.

Nuclear Counterstaining: Apply DAPI (0.5μg/mL) for 5 minutes to visualize nuclei.

Mounting: Mount with anti-fade mounting medium to reduce photobleaching.

Image Acquisition: Image using fluorescence microscope with appropriate filter sets for each fluorophore, ideally within 24 hours to minimize signal degradation.

For multiplex IF beyond 3-4 markers, more sophisticated approaches are required, such as tyramide signal amplification (TSA) or iterative staining methods that involve antibody stripping between rounds of staining [3]. These advanced methods require specialized equipment and validation to ensure signal specificity across multiple cycles.

Figure 2: Comparative Workflows for IHC and IF. Note the critical differences in section thickness, detection systems, and mounting methods that reflect their distinct applications.

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for IHC and IF

| Category | Specific Reagents/Materials | Function | IHC/IF Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixatives | 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin, Paraformaldehyde (PFA), Ethanol/Methanol | Preserve tissue architecture and antigenicity | Both (choice affects antigen retrieval) |

| Antigen Retrieval Buffers | Citrate Buffer (pH 6.0), Tris-EDTA (pH 9.0) | Reverse formaldehyde cross-linking and expose epitopes | Both (buffer selection is antibody-dependent) |

| Blocking Reagents | Normal Serum, BSA, Serum-Free Protein Block | Reduce non-specific antibody binding | Both |

| Enzymes | Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP), Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) | Catalyze chromogen conversion to colored precipitate | IHC only |

| Chromogenic Substrates | DAB (brown), AEC (red), Vector Blue, Vector Red | Form insoluble colored precipitates at antigen sites | IHC only |

| Traditional Fluorophores | FITC, TRITC, Cy3, Cy5 | Emit fluorescence at specific wavelengths upon excitation | IF only |

| Advanced Fluorophores | Alexa Fluor series, BODIPY, Rhodamine derivatives | High brightness, photostability, and pH resistance | IF only (multiplexing applications) |

| Mounting Media | Permanent Mounting Medium, Anti-fade Mounting Media | Preserve slides and reduce signal degradation | Both (choice critical for signal preservation) |

| Counterstains | Hematoxylin, DAPI, Hoechst | Visualize nuclei and tissue architecture | Both (IHC: hematoxylin; IF: DAPI) |

The selection of appropriate fluorophores is particularly critical for successful IF experiments. Key considerations include the Stokes shift (separation between excitation and emission peaks), quantum yield (emission efficiency), and photostability (resistance to photobleaching) [13] [15]. For multiplex IF, careful spectral separation is essential to minimize cross-talk between channels. The Alexa Fluor series generally offers superior brightness and photostability compared to traditional fluorophores like FITC, while cyanine dyes (Cy3, Cy5) provide narrow emission peaks ideal for multicolor experiments [15].

For IHC, the choice of chromogen depends on the application. DAB produces a permanent, alcohol-insoluble brown precipitate that is ideal for archival material and subsequent analysis. Other chromogens like AEC (red) are alcohol-soluble and require aqueous mounting, but may provide better contrast with certain tissues [11]. The enzyme selection (HRP vs. AP) may be influenced by endogenous enzyme activity in the tissue being studied.

Applications and Experimental Data

Diagnostic Concordance and Validation Studies

The clinical application of IHC is well-established in diagnostic pathology, particularly for biomarker assessment in cancer. A prospective study comparing IHC and Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) for HER2 status in breast cancer demonstrated 82% concordance between the methods [16]. However, significant discordance rates were observed in specific subgroups: 30% in IHC 2+ cases, 7.1% in IHC 3+ cases, and 19.2% in IHC 0/1+ cases [16]. This highlights both the utility and limitations of IHC as a screening tool, with FISH serving as a necessary reflex test for ambiguous cases.

The development of virtual staining technologies using artificial intelligence represents an emerging application that bridges both detection methods. Deep generative models can now digitally generate virtual IHC images from H&E-stained samples, potentially offering a cost-effective alternative for biomarker assessment [12]. These approaches frame virtual staining as an image-to-image translation problem, mapping from H&E (source domain) to IHC (target domain) using both paired and unpaired training data [12]. While still in development, such technologies demonstrate how computational methods may eventually augment both IHC and IF workflows.

Multiplexing Capabilities and Spatial Biology

The superior multiplexing capacity of IF enables sophisticated spatial analysis of the tumor microenvironment (TME). Technologies like multiplexed immunohistochemical consecutive staining on single slide (MICSSS) and DNA-barcoded antibody methods now permit detection of 10-60 markers on a single tissue section [3]. This high-plex capability has revealed complex immunophenotypes with clinical significance, such as the density of CD8+CD39+ T cells in non-small cell lung carcinoma and spatial relationships between PD-1+ and PD-L1+ cells in Merkel cell carcinoma [3].

The analytical requirements for multiplex IF data are substantially more complex than for IHC. Analysis pipelines must include color deconvolution (for brightfield multiplex IHC) or spectral unmixing (for multiplex IF), tissue segmentation, cell segmentation, phenotyping, and spatial analysis [3]. These workflows typically require specialized computational tools and validation at each step to ensure data reliability. For multiplex IHC using brightfield microscopy, color deconvolution algorithms separate the contribution of individual chromogens from red, green, blue (RGB) images, generating separate channels for each stain [3].

Practical Application Guidelines

Selection between IHC and IF should be guided by specific research questions and practical constraints:

Choose IHC when:

- Permanent, archivable slides are required for regulatory compliance or clinical diagnostics

- Only 1-2 markers need to be detected simultaneously

- Brightfield microscopy is the only available imaging modality

- Crisp morphology assessment is prioritized for pathologist review

- Lower cost and complexity are essential factors [10]

Choose IF when:

- 3 or more markers need to be detected on the same slide

- Spatial biology and co-localization studies are research priorities

- High sensitivity and dynamic range are required for target detection

- Access to fluorescence imaging systems is available

- Subcellular localization precision is necessary [10]

For drug development applications, the high-plex capability of IF enables comprehensive characterization of the TME and complex immunophenotypes that may predict therapeutic response. The Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer has developed best practice guidelines for multiplex IHC/IF to standardize these applications across laboratories [3].

The detection divide between chromogenic enzymes in IHC and fluorescent dyes in IF represents more than just technical preferences—it reflects fundamental trade-offs between permanence and multiplexing, accessibility and sensitivity, morphology and spatial resolution. IHC remains the workhorse of clinical diagnostics, providing stable, morphologically rich data that integrates seamlessly into pathological assessment. IF enables sophisticated multidimensional analyses that reveal cellular interactions and complex phenotypes within the tissue microenvironment.

The evolving landscape of both technologies points toward increased integration rather than replacement. Computational approaches like virtual staining may eventually bridge these domains, while advanced multiplexing platforms continue to push the boundaries of what can be measured in a single tissue section. For researchers and drug development professionals, the optimal approach often involves leveraging both technologies strategically—using IHC for validated clinical biomarkers and IF for exploratory spatial biology—to comprehensively understand disease mechanisms and therapeutic responses.

In the fields of biomedical research and diagnostics, the accurate detection and quantification of protein biomarkers directly within their native tissue context is fundamental to understanding disease mechanisms and advancing therapeutic development. Two cornerstone techniques—Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and Immunofluorescence (IF)—enable this vital visualization. Despite sharing a common principle of antibody-antigen recognition, their underlying detection chemistries impart distinct performance profiles, particularly regarding inherent sensitivity and dynamic range. These technical characteristics are not merely academic distinctions; they directly influence which biological questions can be reliably answered. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of IHC and IF, framing the discussion within the broader thesis of how detection methodology dictates application suitability, with a focus on the needs of researchers and drug development professionals.

Fundamental Principles and Key Distinctions

At their core, both IHC and IF rely on the specific binding of an antibody to a target antigen. The critical difference lies in the method of signal generation and detection.

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC) utilizes antibodies conjugated to enzymes (such as Horseradish Peroxidase or Alkaline Phosphatase). When a chromogenic substrate (e.g., DAB or AEC) is introduced, the enzyme catalyzes a reaction that produces a colored precipitate at the antigen site. This signal is visible under a standard brightfield microscope and results in a stable, permanent slide that can be archived [17] [10].

- Immunofluorescence (IF) employs antibodies tagged directly or indirectly with fluorescent dyes (fluorophores). When excited by light of a specific wavelength, these dyes emit light of a longer wavelength, creating a visible signal detected by a fluorescence microscope. This approach enables highly multiplexed experiments but is susceptible to photobleaching, where the fluorescent signal fades over time [17].

Table 1: Core Technical Characteristics of IHC and IF

| Parameter | Immunohistochemistry (IHC) | Immunofluorescence (IF) |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Chemistry | Chromogenic enzyme reaction | Fluorescent dye emission |

| Signal Visualization | Brightfield microscope | Fluorescence microscope |

| Signal Stability | Permanent and archivable [10] | Subject to photobleaching [17] |

| Multiplexing Potential | Limited (typically 1-2 markers) [10] | High (2-8+ with traditional IF; 10-60+ with ultra-high-plex platforms) [10] |

| Inherent Resolution | Lower | Higher, enabling superior subcellular localization [17] |

| Best Suited For | Diagnostic workflows, pathologist review, long-term archiving [17] [10] | Spatial biology, co-localization studies, immune cell phenotyping [18] [10] |

Comparative Performance Data: Sensitivity and Dynamic Range in Practice

The theoretical distinctions between IHC and IF translate into measurable differences in assay performance. Sensitivity refers to the lowest concentration of an antigen that can be reliably distinguished from background, while dynamic range defines the span of antigen concentrations over which the assay provides a quantitative response.

Quantitative Evidence from HER2 Assay Development

The challenge of accurately quantifying low-abundance targets is exemplified by HER2 testing in breast cancer. Traditional IHC, while effective for identifying HER2-high amplified cancers, struggles with the limited dynamic range of chromogenic detection, making it difficult to consistently distinguish between low (IHC 1+) and ultra-low (IHC 0) expression levels. This has direct clinical consequences, as this distinction now determines patient eligibility for novel antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) [19]. One study noted that pathologist concordance for this distinction can be as low as 26%, meaning a patient's treatment could depend more on the assessing pathologist than on the tumor's biology [19].

To overcome these limitations, a High-Sensitivity HER2 (HS-HER2) quantitative assay was developed. This method moves beyond subjective pathologist scoring to objective measurement in attomoles per square millimeter (amol/mm²). In a prospective validation study:

- The HS-HER2 assay demonstrated a coefficient of variation below 10%, indicating high precision and reproducibility [20].

- The assay revealed that 71% of cases traditionally scored as IHC=0 actually had HER2 expression levels above the assay's limit of quantification, highlighting the superior sensitivity of quantitative methods over conventional IHC scoring [20].

- This work underscores a broader shift in the field: moving from treating IHC as a qualitative "stain" to regarding it as a quantitative laboratory assay, a transition that requires calibration standards and rigorous analytic validation similar to other diagnostic disciplines like ligand binding assays [21] [19].

The Multiplexing Advantage of Immunofluorescence

The dynamic range of an experiment is also a function of how many targets can be measured simultaneously in a single sample. Here, IF holds a distinct advantage. While IHC is typically limited to 1-2 markers per slide due to color overlap, traditional IF can easily accommodate 2-8 markers [10]. Furthermore, advanced platforms like the Akoya PhenoCycler-Fusion push this further, allowing for the simultaneous detection of 10 to 60 protein biomarkers on a single slide [10]. This ultra-high-plex capability provides a vast "data range," enabling researchers to comprehensively characterize complex cellular microenvironments, such as the tumor immune landscape, without consuming precious sample material across multiple serial sections.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To illustrate how the inherent properties of these techniques are realized in practice, below are detailed methodologies for a key quantitative IHC protocol and a multiplex IF workflow.

Protocol: High-Sensitivity Quantitative HER2 IHC Assay

This protocol is adapted from a validation study for a quantitative HER2 assay [19].

Objective: To objectively quantify HER2 protein expression in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) breast cancer tissue sections in units of amol/mm².

Materials & Reagents:

- FFPE Tissue Sections: Cut at 4 μm thickness.

- Calibration Cell Line Microarray (CMA): Contains cell lines with HER2 concentrations predetermined by mass spectrometry [19].

- Primary Antibody: Validated anti-HER2 antibody.

- Detection System: Chromogenic detection kit (e.g., HRP-DAB).

- Whole-Slide Scanner: For high-resolution digital imaging.

- Image Analysis Software: For quantitative analysis of stain intensity.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Co-stain a batch of patient FFPE sections and the calibration standard CMA slide.

- Slide Scanning: Digitize all stained slides using a whole-slide scanner at a consistent resolution.

- Image Analysis: Use software to quantify the chromogenic signal intensity in the tumor regions of patient samples.

- Calibration: Generate a standard curve by plotting the known HER2 concentration (amol/mm²) of the calibration cell lines against their measured signal intensities.

- Quantification: Interpolate the signal intensity from the patient's tumor against the standard curve to determine the absolute HER2 concentration.

Data Interpretation: This method transforms subjective scoring (0, 1+, 2+, 3+) into a continuous, objective quantitative measurement, directly addressing the dynamic range limitations of conventional IHC for low-abundance targets [19].

Protocol: Multiplex Immunofluorescence with Cyclic Staining

This protocol outlines the principle behind advanced multiplex IF methods like those used in the ROSIE AI framework [18].

Objective: To simultaneously visualize the expression and spatial distribution of dozens of protein biomarkers in a single FFPE tissue section.

Materials & Reagents:

- FFPE Tissue Sections: Cut at 5-7 μm thickness, slightly thicker than for IHC to preserve tissue [10].

- Antibody Panels: Primary antibodies for multiple targets, validated for IF.

- Fluorophore-Conjugated Secondary Antibodies: Or tyramide signal amplification (TSA) reagents.

- Fluorescence Microscope or Scanner: Equipped with multiple filter sets for different fluorophores.

- CODEX or Similar System: For co-detection by indexing or other cyclic staining platforms [18].

Methodology:

- Staining Cycle 1: Apply a first set of primary antibodies, followed by fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies or TSA reaction.

- Imaging: Image the slide to capture the signal from the first set of markers.

- Fluorophore Inactivation: Gently remove or chemically inactivate the fluorophores without damaging the tissue or the antigens.

- Repetition: Repeat steps 1-3 with a new set of antibodies for different targets.

- Image Alignment and Analysis: Computational alignment of all imaging cycles to generate a composite, highly multiplexed image for cell phenotyping and spatial analysis [18].

Data Interpretation: This cyclic approach overcomes the physical limitation of spectral overlap, allowing for the detection of dozens of markers. The resulting data is rich in spatial context, enabling the identification of complex cell phenotypes and their interactions within the tissue microenvironment.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The execution of high-quality IHC and IF experiments relies on a suite of key reagents and tools.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for IHC and IF

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Primary Antibodies | Specifically binds the target antigen of interest. | Critical to select antibodies validated for the specific application (IHC or IF) and sample type (e.g., FFPE, frozen) [22]. |

| Chromogenic Substrates (DAB, AEC) | Enzyme substrate that produces a colored precipitate in IHC. | DAB provides a permanent, insoluble stain. Requires careful handling as a potential carcinogen. |

| Fluorophores (e.g., FITC, TRITC) | Fluorescent dye that emits light upon excitation in IF. | Prone to photobleaching. Panel design must consider spectral overlap to minimize bleed-through [17]. |

| Calibration Standards | Provides a reference for converting signal intensity to quantitative units. | Essential for quantitative IHC assays (e.g., HER2); enables inter-laboratory reproducibility and analytic rigor [21] [19]. |

| Antigen Retrieval Buffers | Unmasks epitopes cross-linked during formalin fixation. | Citrate and Tris-EDTA are common; optimal buffer and pH are antigen-dependent and require optimization. |

| Image Analysis Software | Quantifies signal intensity, cell counts, and spatial relationships. | For IHC, can outperform pathologist readout in accuracy for quantitative tasks; for IF, enables complex multiplex data deconvolution [21] [18]. |

Visualizing Workflows and Relationships

The following diagrams illustrate the core workflows of IHC and IF, as well as the logical decision process for selecting the appropriate technique.

IHC and IF Core Workflow Comparison

Technique Selection Logic

The technical comparison between IHC and IF reveals a landscape defined by trade-offs. IHC offers permanence, simplicity, and seamless integration into diagnostic workflows, but its utility is constrained by limited multiplexing capability and a subjective, often narrow dynamic range for quantitative applications. IF provides superior sensitivity, a wider effective dynamic range for detecting expression levels, and unparalleled capacity for multiplexing, which is crucial for dissecting complex biological systems, though it requires more sophisticated instrumentation and faces challenges with signal permanence.

The emerging thesis is that the choice between IHC and IF is not about finding a universal "best" technique, but rather about aligning the tool with the question. For diagnostic pathology and archival studies requiring long-term sample stability, IHC remains foundational. For discovery-phase research, spatial biology, and detailed immune profiling, IF and its ultra-high-plex successors are indispensable. The future of protein detection in tissues lies in the continued push towards quantification, standardization, and integration. The development of calibrated IHC assays and computational tools like ROSIE, which can predict protein expression from H&E images, blurs the lines between these techniques, pointing toward a future where the combined strengths of both methods will power a deeper, more quantitative understanding of disease biology [18] [21] [19].

The study of complex tissue microenvironments, particularly in immuno-oncology and drug development, has long been hampered by technological limitations. Traditional immunohistochemistry (IHC), while foundational in pathology, operates within a constrained "one-marker-per-slide" paradigm that provides limited insight into the intricate cellular ecosystems driving disease progression and therapeutic response [8]. The evolution from single-plex assays to multiplexed immunohistochemistry (mIHC) and ultimately to ultra-high-plex immunofluorescence (IF) represents a transformative shift in how researchers visualize, quantify, and understand spatial biology. This progression is fundamentally reshaping biomarker discovery and validation by enabling comprehensive profiling of complex immunophenotypes and spatial relationships within the tumor microenvironment (TME) [3]. The driving thesis behind this technological evolution is that fluorescence-based multiplexing offers superior sensitivity, dynamic range, and multiplexing capacity compared to traditional chromogenic detection, thereby providing previously unattainable insights into disease mechanisms and treatment effects [10] [11]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this evolution is critical for selecting appropriate platforms that balance practical constraints with the necessary biological depth for their specific applications.

Historical Foundations: From Single-Plex IHC to Multiplexed Approaches

The journey toward multiplexed tissue analysis began with foundational techniques that established the core principles of antibody-based antigen detection. Immunofluorescence itself dates to the 1940s, when Albert H. Coons and colleagues developed fluorescein-labeled antibodies to detect pneumococcal antigens in infected tissues [8]. This pioneering work demonstrated the potential of antibody-based detection but remained technically challenging for widespread adoption. Concurrently, the development of enzyme-conjugated antibodies in the 1960s, particularly with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and alkaline phosphatase (AP), provided more accessible and stable detection methods that became the cornerstone of traditional IHC [11] [8].

The limitations of single-plex assays became increasingly apparent as researchers sought to understand complex biological systems. Traditional IHC, while excellent for detecting single antigens with clear morphological context, proved inadequate for studying cell-cell interactions, heterogeneous cell populations, and complex protein co-expression patterns [17] [10]. The initial breakthrough in multiplexing came with sequential staining approaches that allowed limited detection of 2-3 markers, though these were often hampered by antibody cross-reactivity and signal overlap issues [23]. A significant conceptual advance was the development of tyramide signal amplification (TSA) in the 1990s, which provided the sensitivity and signal confinement necessary for true multiplexed detection by enabling iterative rounds of staining, imaging, and signal inactivation [23]. This technological progression established the foundation for contemporary ultra-high-plex platforms, enabling researchers to move beyond simple marker detection toward comprehensive cellular cartography.

Technical Comparison of Multiplexing Platforms

The landscape of multiplexing technologies spans a continuum from basic chromogenic multiplexing to sophisticated cyclic fluorescence approaches, each with distinct advantages, limitations, and appropriate applications. Understanding these technical differences is essential for selecting the optimal platform for specific research questions.

Table 1: Comparison of Multiplexing Platforms and Their Capabilities

| Platform Type | Max Markers per Section | Detection Chemistry | Imaging Area | Key Applications | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Plex IHC | 1-2 | Chromogenic enzymes (HRP/AP + DAB, AEC) | Whole slide | Diagnostic pathology, archival studies | Limited multiplexing; moderate sensitivity [10] |

| Multiplex IHC | 3-5 | Simultaneous/sequential chromogenic without marker removal | Whole slide | Basic cell typing, limited co-localization | Spectral overlap; semi-quantitative [3] [23] |

| Multiplex IF | 5-8 (TSA-based); 30-60 (non-TSA cyclical) | Cyclical stain/stripping, TSA amplification, or DNA barcodes | Up to whole slide | Spatial biology, immune cell interactions | Photobleaching risk; specialized equipment needed [3] [10] |

| MICSSS | 10+ | Iterative immunostaining, scanning, and removal | Whole slide | Deep phenotyping across tissue architectures | Time-intensive; complex protocol optimization [3] |

| Digital Spatial Profiling | 40-50 | UV-cleavable fluorescent DNA tags | ROI (0.28 mm², tiling possible) | Targeted transcriptome/proteome with spatial context | Limited field of view; specialized instrumentation [3] |

The transition from chromogenic to fluorescence-based detection represents a critical inflection point in multiplexing capabilities. Chromogenic IHC, while producing stable, archivable slides compatible with standard brightfield microscopy, faces fundamental limitations in multiplexing capacity due to color spectral overlap and the semi-quantitative nature of optical density measurements [10] [23]. In contrast, fluorescence detection enables superior sensitivity and dynamic range through spectral separation, allowing researchers to distinguish multiple markers simultaneously through discrete emission wavelengths [11]. This fluorescence advantage is further enhanced by signal amplification technologies like TSA, which can improve sensitivity by up to 100-fold compared to conventional methods through covalent, spatially restricted deposition of fluorophores [23]. For ultra-high-plex applications, cyclic approaches that involve repeated rounds of staining, imaging, and fluorophore inactivation or antibody stripping have pushed multiplexing boundaries to 60+ markers on a single tissue section, enabling unprecedented depth in cellular phenotyping and spatial analysis [3] [24].

Figure 1: The Technical Evolution of Multiplexing Platforms

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Considerations

Implementing robust multiplex IF assays requires careful attention to protocol optimization, validation, and quality control across the entire workflow. The following section details key methodological considerations for generating high-quality, reproducible multiplex IF data.

Sample Preparation and Validation

Proper tissue handling begins with appropriate fixation to preserve morphological detail while maintaining antigenicity. Formalin-based fixatives (10% neutral buffered formalin or 4% paraformaldehyde) provide excellent tissue penetration and morphological preservation through methylene cross-links between proteins, though overfixation can mask epitopes and require antigen retrieval [11]. For multiplex IF, tissue sections of 4-5μm thickness are recommended, with careful attention to avoiding folds, tears, or debris during sectioning [24] [10]. Antigen retrieval is particularly critical for formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues, with heat-induced epitope retrieval (HIER) using citrate or Tris-EDTA buffers at pH 6.0 or 9.0 being most common [10] [25]. Validation should include both positive controls (tissues or cell lines with known antigen expression) and negative controls (omission of primary antibody, isotype controls) to establish assay specificity and sensitivity [8] [23]. For ultra-high-plex panels, antibody validation should be performed initially as single-plex stains under the intended experimental conditions to verify specificity, optimal dilution, and subcellular localization before combining into multiplex panels [3] [23].

Staining Protocols for Varying Multiplex Levels

The complexity of staining protocols escalates significantly with increasing plex level, requiring different approaches and quality control measures at each tier.

Table 2: Staining Methodologies Across Multiplexing Levels

| Multiplex Level | Staining Approach | Signal Detection | Key Quality Metrics | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Plex (2-4 markers) | Simultaneous primary antibody application | Fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies | Signal-to-noise ratio; spectral cross-talk | Basic co-localization studies; diagnostic applications |

| Mid-Plex (5-8 markers) | Sequential staining with gentle stripping | TSA amplification with fluorophores | Batch-to-batch variation; stripping efficiency | Immune cell phenotyping; tumor-stroma interactions |

| High-Plex (10-30 markers) | Iterative cycles of staining/imaging | DNA-barcoded antibodies; fluorophore cycling | Marker intensity stability; registration accuracy | Comprehensive TME mapping; cellular neighborhood analysis |

| Ultra-High-Plex (30-60+ markers) | Automated cyclic staining systems | Oligonucleotide cleavage & detection | Tissue integrity throughout cycles; imaging artifacts | Systems-level biology; biomarker discovery; clinical trial analysis |

For mid-to-high-plex experiments employing TSA, the protocol typically involves: (1) initial antigen retrieval and blocking; (2) application of primary antibody against first target; (3) HRP-conjugated secondary antibody incubation; (4) tyramide-fluorophore conjugation and deposition; (5) antibody stripping via low-pH buffer or heat treatment; and (6) repetition of steps 2-5 for subsequent targets [23]. Each cycle requires rigorous validation to ensure complete antibody removal while preserving tissue integrity and antigenicity for subsequent rounds. For ultra-high-plex approaches using DNA barcoding, the process involves labeling primary antibodies with oligonucleotide barcodes, followed by sequential hybridization with complementary fluorescent reporters across multiple cycles [3]. Throughout all protocols, careful panel design is essential, considering species/isotype compatibility, epitope stability across staining cycles, and fluorophore spectral characteristics to minimize cross-talk [23].

Image Acquisition and Analysis Workflows

Image acquisition for multiplex IF requires specialized instrumentation and standardized approaches to ensure data quality. Whole-slide imaging is increasingly preferred over region of interest (ROI) selection to capture tissue heterogeneity and enable automated hotspot detection, though it demands significant computational resources [3]. For fluorescence-based multiplexing, image acquisition protocols must define appropriate microscope objectives, exposure times for each filter set, and z-stacking parameters if needed [3]. Spectral unmixing is critical for resolving fluorophore emission spectra, particularly when using TSA-based approaches with overlapping emission profiles [3] [23]. Following acquisition, image analysis workflows typically involve: (1) color deconvolution or spectral unmixing to generate individual marker channels; (2) tissue and cell segmentation to identify nuclear, cytoplasmic, and membrane boundaries; (3) phenotyping based on marker expression thresholds; and (4) spatial analysis to quantify cell-cell interactions and organizational patterns [3]. Verification of analysis algorithms is essential, particularly for cell segmentation and phenotyping steps, through comparison with pathologist annotation or other validated methods [3].

Figure 2: Comprehensive Workflow for Multiplex IF Analysis with Quality Control Checkpoints

Quality Control and Artifact Management

The complexity of multiplex IF workflows introduces multiple potential sources of artifacts that can compromise data quality and interpretation. Effective quality control (QC) measures are essential throughout the entire process, from tissue preparation to final analysis. Tissue folds, optical aberrations, and staining artifacts such as antibody aggregates can create discrete clusters in single-cell feature space that obscure true biological signals [24]. Similarly, imaging artifacts including out-of-focus regions, tile stitching errors, and fluorescence bleed-through can significantly impact downstream analysis [3] [24]. In cyclic multiplexing approaches, additional artifacts such as tissue loss between rounds and registration errors from tissue movement must be monitored [24].

Advanced computational tools like CyLinter have been developed specifically to identify and remove data associated with these imaging artifacts [24]. This software operates within the Napari image viewer platform and enables interactive quality control by flagging regions affected by folds, debris, antibody aggregates, and other technical artifacts that dramatically impact single-cell analysis [24]. Implementation of such tools is particularly valuable for archival specimens, which are often more susceptible to artifacts due to prolonged storage [24]. Additional QC measures should include batch-to-batch correction to account for technical variation across different staining runs and verification of cell segmentation algorithms through comparison with manual annotation [3]. These comprehensive quality control approaches are essential for generating robust, reproducible data, particularly in multi-institutional studies where harmonization across platforms and laboratories is challenging [3].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of multiplex IF requires careful selection and validation of core reagents that form the foundation of reliable assays. The following table details essential materials and their functions within the multiplex IF workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Multiplex Immunofluorescence

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Antibodies | Recombinant monoclonal antibodies; validated clones | Target antigen recognition | Specificity, lot-to-lot consistency, host species [23] |

| Signal Amplification Reagents | Tyramide conjugates (TSA); polymer systems | Signal enhancement | Sensitivity, spatial resolution, compatibility with multiplex cycles [23] |

| Fluorophores | Alexa Fluor dyes; Cyanine dyes | Signal generation | Spectral properties, brightness, photostability [11] [23] |

| Antigen Retrieval Buffers | Citrate buffer (pH 6.0); Tris-EDTA (pH 9.0) | Epitope unmasking | pH optimization for specific antigens [10] [25] |

| Blocking Reagents | Normal serum; protein blocks; Fab fragments | Reduction of non-specific binding | Compatibility with multiple antibody species [25] |

| Nuclear Counterstains | DAPI; Hoechst stains | Cell segmentation and identification | Spectral separation from marker channels [25] |

| Mounting Media | ProLong Diamond; Vectashield | Slide preservation and signal maintenance | Anti-fade properties; compatibility with imaging [10] |

For ultra-high-plex panels, antibody validation is particularly critical and should include testing on control tissues with known expression patterns, verification of subcellular localization, and assessment of performance under the specific fixation and retrieval conditions to be used in the final assay [23]. Panel design must carefully consider species and isotype compatibility when using secondary detection methods, with optimal panels utilizing primary antibodies from different species to minimize cross-reactivity [23]. For fluorescent detection, fluorophore selection requires attention to spectral overlap, with sufficient separation between emission peaks to enable clear discrimination during imaging and analysis [23]. The emergence of DNA-barcoded antibodies has been particularly transformative for ultra-high-plex applications, as they enable highly multiplexed detection through sequential hybridization approaches while minimizing spectral constraints [3].

Applications and Impact on Biomedical Research

The evolution of multiplexing technologies has opened new frontiers in biomedical research, particularly in immuno-oncology, neuroscience, and inflammatory disease research. In cancer immunotherapy development, multiplex IF has enabled the identification of complex biomarkers that predict treatment response with unprecedented accuracy. For example, quantification of intratumoral CD8+CD39+ cells or the density of CD8+FoxP3+ T cells in non-small cell lung carcinoma has demonstrated area under the curve (AUC) values of approximately 0.8 for predicting response to anti-PD-(L)1 therapies, outperforming traditional single-plex biomarkers like PD-L1 IHC [3]. Similarly, combinatorial biomarkers incorporating multiple cell populations have shown superior predictive value in advanced melanoma [3]. These applications highlight how multiplex IF moves beyond simple cell counting to reveal functional relationships between cell types within the tissue architecture.

The technology has proven equally transformative for understanding disease mechanisms through detailed characterization of the tumor microenvironment (TME). Multiplex IF has enabled categorization of TMEs into distinct geographic "immunotypes" based on the spatial organization and functional orientation of immune cells, providing insights into immune escape mechanisms and potential therapeutic vulnerabilities [3]. In neuroscience, multiplex IF has illuminated complex cell-type interactions in neurodegenerative diseases, while in infectious disease research, it has revealed spatial aspects of host-pathogen interactions [8]. The ability to simultaneously assess immune cell densities, functional marker expression, and spatial distributions within specific tissue compartments (e.g., tumor core vs. invasive margin) provides a systems-level understanding of disease biology that was previously unattainable with sequential single-plex approaches [3] [10]. As these technologies continue to mature, they are increasingly being applied in clinical trial contexts to identify patient subsets most likely to respond to targeted therapies and to understand mechanisms of treatment resistance [24].

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

The evolution from single-plex to ultra-high-plex IF represents a paradigm shift in how researchers approach tissue-based research, moving from reductionist analysis of individual components toward systems-level understanding of cellular ecosystems. This progression has been driven by continuous advances in detection chemistries, imaging platforms, and computational analysis tools that have collectively expanded multiplexing capabilities while improving quantification accuracy and reproducibility. The integration of digital pathology and artificial intelligence represents the next frontier in this evolution, enabling automated interpretation of complex staining patterns and extraction of subtle morphological features that may not be apparent through manual analysis [8]. As these technologies mature, we can anticipate increased standardization and harmonization across platforms, facilitating multi-institutional studies and potentially supporting regulatory decision-making [3].

Despite these advances, challenges remain in making ultra-high-plex technologies accessible to broader research communities, standardizing analytical approaches, and managing the computational demands of whole-slide, high-plex image analysis [3] [24]. The future will likely see continued innovation in both wet-lab methodologies and computational tools, with particular emphasis on integrating multiplex protein detection with transcriptomic and genomic data to create comprehensive molecular portraits of tissue organization and function [24]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this technological evolution is essential for selecting appropriate platforms that balance practical constraints with the necessary biological depth for specific applications. As multiplex IF continues to evolve toward clinical implementation, establishing robust validation frameworks and quality control standards will be paramount for ensuring that these powerful technologies deliver on their promise to transform both basic research and clinical practice.

For researchers in drug development and biomedical sciences, choosing between brightfield and fluorescence microscopy is a critical decision that impacts experimental design, data quality, and resource allocation. This guide provides an objective comparison of both techniques, focusing on their hardware requirements, performance characteristics, and applications in immunohistochemistry (IHC) and immunofluorescence (IF).

Core Technical Specifications

The fundamental differences between brightfield and fluorescence microscopy begin with their basic optical configurations and hardware requirements.

Basic Equipment Requirements for Brightfield and Fluorescence Microscopy

Brightfield Microscopy Equipment

- Light Source: Standard halogen or LED transmitted light source

- Optics: Conventional objectives (e.g., 20x Plan Apochromat), no specialized filters required

- Detector: Standard color CMOS or CCD camera sufficient

- Sample Requirements: Typically requires staining with chromogenic dyes like hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for contrast [8] [26]

Fluorescence Microscopy Equipment

- Light Source: High-intensity sources (lasers, mercury/xenon arc lamps, or high-power LEDs) with specific wavelengths [27]

- Optics: High numerical aperture (NA) objectives, specialized filter sets (excitation/emission/dichroic) [28] [27]

- Detector: Sensitive detectors (sCMOS cameras, PMTs, or GaSP detectors) with high quantum efficiency [28] [27]

- Sample Requirements: Fluorophore-conjugated antibodies or fluorescent proteins required for specific labeling [11]

Performance Comparison & Experimental Data

Direct comparisons of brightfield and fluorescence microscopy reveal significant differences in their analytical capabilities, particularly for mechanism of action (MoA) studies and cellular analysis.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison for MoA Prediction

| Performance Metric | Brightfield Microscopy | Fluorescence Microscopy | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| MoA Prediction Accuracy | Comparable to fluorescence | Reference standard | Deep learning models predicting 10 MoA classes [29] |

| Cellular Contrast | Low native contrast | High specific contrast | U2OS cells, 48h compound treatment [29] |

| Information Content | Additional temporal information in live cells | Limited by phototoxicity | Brightfield superior for live-cell time-lapse [29] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Limited | 3-5 targets (IHC), 5-60+ targets (IF) | Dependent on staining approach [3] |

| Phototoxicity | Minimal | Significant concern | Fluorescence dyes can be toxic to cells [29] |

Table 2: Experimental Considerations for Imaging Applications

| Parameter | Brightfield Microscopy | Fluorescence Microscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Live-Cell Compatibility | Excellent | Limited due to phototoxicity and dye cytotoxicity [29] |

| Spatial Resolution | Diffraction-limited | Diffraction-limited, with super-resolution techniques available [28] |

| Cost & Complexity | Lower | Higher (specialized filters, light sources, detectors) [29] [28] |

| Sample Preparation | Simpler | More complex (fixation, permeabilization, staining) [11] |

| Throughput | High | Moderate (potential for photobleaching) [29] |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Brightfield Image Analysis for Cellular Segmentation

Advanced computational approaches can extract meaningful data from brightfield images, despite their inherent low contrast:

- Z-stack Acquisition: Capture multiple focal planes (typically 6-20 z-slices) at regular intervals [30]

- Contrast Enhancement Projection: Calculate variation measures (standard deviation, interquartile range) across z-dimension to create high-contrast 2D projection images [30]

- Automated Segmentation: Use CellProfiler or deep learning models (U-Net) for cell identification and segmentation [29] [30]

- Validation: Compare results with fluorescent whole-cell stains to verify accuracy [30]

Fluorescence Microscopy Standardization Protocol

For quantitative fluorescence imaging, standardization is essential for reproducibility:

- System Calibration: Regular measurement of illumination power using calibrated power meters [28]

- Spatial Resolution Assessment: Use sub-diffraction sized fluorescent beads (100 nm) to determine point-spread function [28]

- Detector Characterization: Evaluate sensitivity, linearity, and signal-to-noise ratio using reference materials [28]

- Reference Materials: Implement fluorescent-patterned glass slides or DNA-origami probes for routine benchmarking [28]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Microscopy Applications

| Reagent/Category | Function | Brightfield Examples | Fluorescence Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear Stains | Identifies cell locations | Hematoxylin [8] | DAPI, Sytox Green, Hoechst stains [26] [30] |

| Cytoplasmic Stains | Visualizes cell boundaries | Eosin Y [8] [26] | Phalloidin (actin stain) [30] |

| Fixation Methods | Preserves tissue architecture | Formalin, paraformaldehyde [11] | Formaldehyde, methanol [11] |

| Mounting Media | Preserves samples for imaging | Aqueous mounting media | Anti-fade reagents (Prolong Diamond) [27] |

| Antibody Types | Target-specific detection | Enzyme-conjugated (HRP) [8] | Fluorophore-conjugated (Alexa Fluor dyes) [11] |

Advanced Applications & Workflow Integration

The choice between brightfield and fluorescence microscopy often depends on the specific research application and experimental workflow.

Decision Workflow for Microscope Selection Based on Research Application

Brightfield Dominant Applications

- Live-Cell Time-Lapse Experiments: Superior for extended imaging due to minimal phototoxicity [29]

- 3D Histology: Combined with tissue clearing techniques for volumetric analysis of large specimens [26]

- Virtual Staining: Machine learning approaches to predict fluorescent patterns from brightfield images [31] [32]

Fluorescence Dominant Applications

- Multiplexed Target Detection: Simultaneous visualization of multiple cellular targets using spectral separation [3] [11]

- Super-Resolution Imaging: Techniques such as STED and SIM that overcome diffraction limits [28]

- Dynamic Process Tracking: Real-time monitoring of molecular interactions and organelle dynamics [32]

Both brightfield and fluorescence microscopy offer distinct advantages for different research scenarios. Brightfield microscopy provides a cost-effective, live-cell compatible solution that, when enhanced with computational tools, can achieve performance comparable to fluorescence for applications like MoA prediction [29]. Fluorescence microscopy remains essential for high-specificity multiplexed detection and subcellular localization studies, despite its higher complexity and potential phototoxicity [29] [28]. The emerging trend of combining both modalities, using brightfield for primary imaging and fluorescence for validation or specific targeting, represents a powerful approach that maximizes the strengths of both techniques while mitigating their respective limitations [31] [32].

Strategic Applications: Choosing IHC or IF for Diagnostics and Complex Research

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) remains a cornerstone technique in clinical diagnostics, providing critical insights into disease biology by visualizing protein expression within the context of intact tissue architecture. This guide objectively compares IHC's performance against immunofluorescence (IF) and other alternatives, supported by experimental data and validation protocols relevant to researchers and drug development professionals.

Technique Comparison: IHC vs. Immunofluorescence (IF)

The choice between IHC and IF is fundamental and depends on the experimental or diagnostic goals. The core difference lies in their detection methods: IHC uses enzymes to produce a stable, colored precipitate, while IF uses fluorescent dyes that emit light at specific wavelengths [17] [33] [25].

Table: Core Technical and Operational Comparison of IHC and IF.

| Parameter | Immunohistochemistry (IHC) | Immunofluorescence (IF) |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Chemistry | Chromogenic enzymes (e.g., HRP/AP with DAB) [10] [25] | Fluorophores (e.g., FITC, TRITC) [33] [10] |

| Detection Microscope | Brightfield microscope [10] | Fluorescence microscope [33] [10] |

| Signal Duration | Permanent and archivable [17] [10] | Temporary; subject to photobleaching [17] [33] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Limited, typically 1-2 markers [10] | High; traditional IF (2-8 markers), ultra-high-plex IF (10-60 markers) [10] |

| Resolution | Lower resolution for fine structures [33] | High resolution, ideal for subcellular localization [17] [33] |

| Best Applications | Diagnostic pathology, regulatory archiving, crisp morphology review [17] [10] | Spatial biology, co-localization studies, tumor microenvironment analysis [17] [10] |

Experimental Data and Validation Protocols

Robust validation is paramount for deploying IHC in clinical trials and diagnostics. The following data and methodologies illustrate the rigorous processes involved.

Clinical-Grade IHC Assay Validation (NCI-MATCH Trial)

The NCI-MATCH (EAY131) trial established a comprehensive validation framework for therapy-guiding IHC assays [34]. The multi-step protocol ensures analytical validity and reproducibility.

- Primary Antibody Selection: The process begins with a thorough understanding of the target protein and its gene. Antibodies are selected based on peer-reviewed data demonstrating sensitivity and specificity, with preference for commercial vendors adhering to Good Manufacturing Practices to ensure supply continuity and minimal lot-to-lot variation [34].

- Assay Optimization: This step determines the optimal antibody dilution, antigen retrieval conditions (e.g., pH of retrieval solution), and incubation time. The goal is to find the combination that produces the optimal signal-to-noise ratio, often using automated staining platforms for consistency [34].

- Interpretation Criteria and Reporting: Validation includes defining precise interpretation guidelines incorporating biological expectations (e.g., nuclear vs. cytoplasmic staining). To avoid ambiguity, results are reported descriptively (e.g., "loss of expression" or "retained expression" for tumor suppressors like PTEN) rather than simply "positive" or "negative" [34].

Table: Validated Assay Conditions from the NCI-MATCH Trial. [34]

| Biomarker | Clone | Host | Vendor | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTEN | 6H2.1 | Mouse | Dako | 1:100 |

| RB | LM95.1 | Mouse | EMD Millipore/Calbiochem | 1:30 |

| MLH1 | G168-728 | Mouse | Millipore Sigma/Cell Marque | 1:300 |

| MSH2 | FE11 | Mouse | EMD Millipore/Calbiochem | 1:100 |

Calibration for Reproducibility (CASI-01 Study)

A major challenge in IHC, particularly for low-abundance targets like HER2-low in breast cancer, is inter-laboratory variability. The international CASI-01 study demonstrated that calibration using reference standards dramatically improves accuracy and reproducibility. The study found that without calibration, HER2 assay results were highly variable, but calibrated IHC enhanced test reliability and analytical sensitivity, ensuring patients eligible for targeted therapies are correctly identified [21].

AI-Powered IHC Prediction from H&E Stains

Emerging deep learning models can predict IHC biomarker status directly from hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained whole slide images (WSIs), offering a faster and less tissue-consuming alternative. One study developed models for five IHC biomarkers (P40, Pan-CK, Desmin, P53, Ki-67) in gastrointestinal cancers [35].

- Methodology: An automated pipeline, HEMnet, was used to align IHC and H&E WSIs from the same tissue block, transferring IHC labels to the H&E images. A semi-supervised deep learning model (Mean Teacher framework with a ResNet-50 backbone) was then trained on 415,463 tiles extracted from 134 WSIs to predict IHC positivity [35].

- Performance Data: The models achieved high accuracy, demonstrating the potential of AI as an assistive tool in diagnostics [35].

Table: Performance of Deep Learning Models for IHC Biomarker Prediction. [35]

| Biomarker | Area Under the Curve (AUC) | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| P40 | 0.96 | 90.81% |