IHC vs Western Blot: A Comprehensive Guide to Protein Detection Methods

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a detailed comparison of Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and Western Blot, two cornerstone techniques for protein analysis.

IHC vs Western Blot: A Comprehensive Guide to Protein Detection Methods

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a detailed comparison of Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and Western Blot, two cornerstone techniques for protein analysis. It explores their foundational principles, distinct methodological workflows, and ideal applications, from cancer diagnostics to infectious disease detection. The content delivers practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for both techniques, emphasizes the critical role of antibody validation and controls for reproducibility, and concludes with a forward-looking perspective on their place in the evolving proteomics landscape.

Core Principles: How IHC and Western Blot Work from Sample to Signal

In the fields of molecular biology and biomedical research, the specific interaction between an antibody and its target antigen is a foundational principle that enables the detection and analysis of proteins. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and Western blot (WB) are two cornerstone techniques that exploit this specificity, yet they deliver fundamentally different information about the protein of interest. While IHC provides precise spatial localization within a tissue context, Western blot offers quantitative data on protein molecular weight and expression levels. This guide objectively compares the performance, applications, and limitations of these two widely used methods to inform researchers and drug development professionals in selecting the appropriate technique for their experimental goals.

Historical Development and Technical Principles

A Shared Foundation in Immunodetection

Both IHC and Western blotting rely on the specific binding of antibodies to target antigens, a principle pioneered by Albert H. Coons in the 1940s when he developed fluorescently-labeled antibodies to detect pneumococcal antigens in tissues [1] [2]. The core concept shared by both techniques is the utilization of primary antibodies that recognize specific epitopes on the target protein, followed by detection with labeled secondary antibodies or other detection systems.

Western blotting emerged later in 1979, developed from DNA blotting techniques and named in reference to its predecessor methods [3] [4]. The technique was refined by multiple research groups, including Towbin et al. and Burnette, who established the standard protocol of separating proteins by electrophoresis followed by transfer to membranes for antibody detection [4].

Fundamental Technical Differences

Despite their shared reliance on antibody-antigen interactions, IHC and Western blot differ significantly in their approach to sample preparation and protein detection:

- IHC preserves the structural integrity of tissues through fixation and embedding, allowing visualization of protein distribution within their native morphological context [1] [2].

- Western blot involves denaturing proteins through lysis and boiling in SDS-containing buffers, separating them by molecular weight via electrophoresis, then transferring to membranes for detection [3] [4].

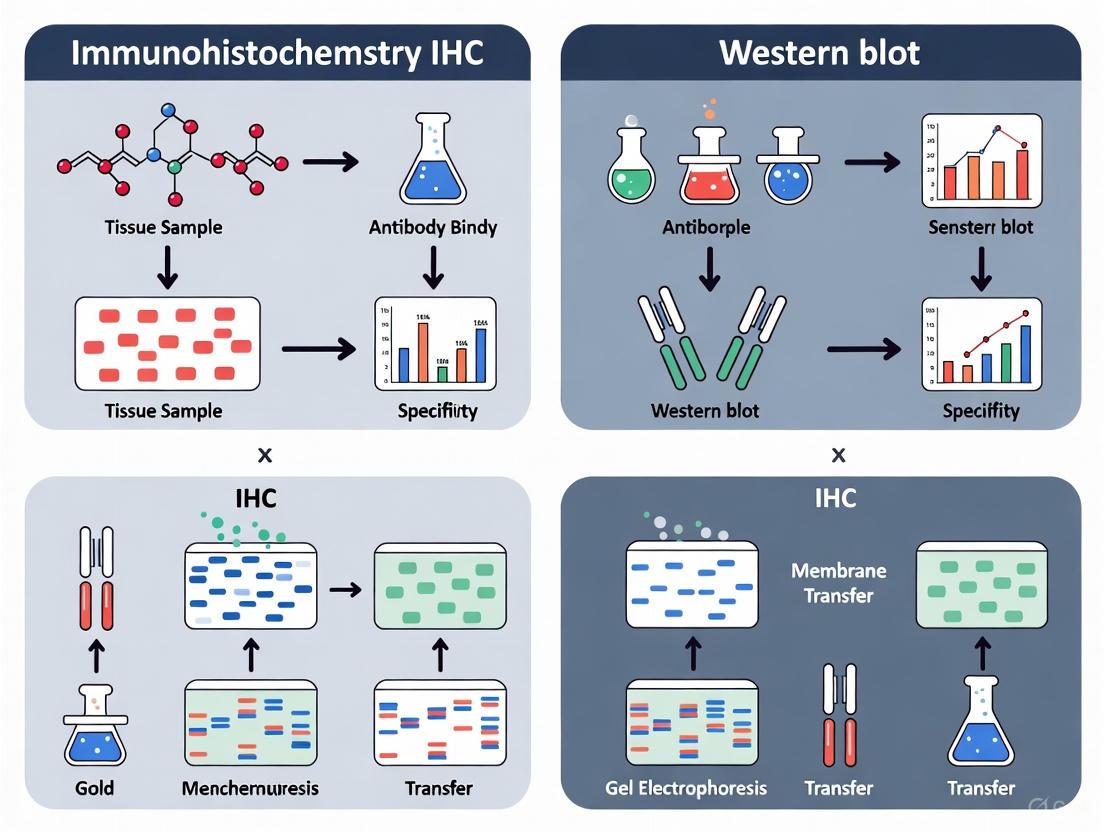

Figure 1: Comparative Workflows of IHC and Western Blot Techniques

Comparative Performance Analysis

Application-Specific Strengths and Limitations

The choice between IHC and Western blot depends heavily on the research question, as each technique offers distinct advantages and suffers from particular limitations.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of IHC and Western Blot

| Parameter | Immunohistochemistry (IHC) | Western Blot |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Information | Preserves tissue architecture and subcellular localization [1] [5] | Destroys tissue context; provides molecular weight information [6] [4] |

| Quantification Capability | Semi-quantitative at best; subjective interpretation [1] | Semi-quantitative to quantitative; can compare expression levels between samples [3] [4] |

| Sensitivity | High with signal amplification methods (e.g., ABC, polymer-based) [7] | Very high; can detect low abundance proteins [5] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Limited for chromogenic; better for fluorescent detection (3-4 targets) [2] [7] | Limited by antibody species and molecular weight; typically 2-3 targets [2] |

| Throughput | Lower throughput; manual assessment often required [1] | Medium throughput; can process multiple samples simultaneously [3] |

| Protein State | Proteins in near-native state within tissue context [2] | Denatured proteins; epitopes may be altered [3] |

| Diagnostic Utility | Essential for pathological diagnosis; provides morphological context [1] [6] | Limited diagnostic use; primarily research tool [6] [4] |

Detection Methods and Signal Visualization

Both techniques employ similar detection strategies but with different practical implementations:

IHC Detection Systems:

- Chromogenic detection: Enzymes like HRP convert substrates (DAB, AEC) to insoluble colored precipitates at antigen sites [7]. Advantages include permanent slides and common microscope compatibility.

- Fluorescent detection: Fluorophore-conjugated antibodies emit light at specific wavelengths when excited [2] [7]. Allows multiplexing but susceptible to photobleaching.

- Signal amplification: Methods like Avidin-Biotin Complex (ABC) or polymer-based systems enhance sensitivity through enzyme clustering [7].

Western Blot Detection:

- Chemiluminescent: HRP-conjugated antibodies catalyze light emission upon substrate addition, detected by X-ray film or digital imagers [3].

- Fluorescent: Direct detection with fluorophore-conjugated antibodies enables multiplexing and digital quantification [3] [5].

- Colorimetric: Less common; produces colored precipitates on the membrane [3].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Detailed IHC Protocol for Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) Tissues

Sample Preparation and Fixation:

- Tissue fixation: Immerse tissue in 10% neutral buffered formalin (approximately 4% formaldehyde) for 24-48 hours [1] [2]. Adequate fixation preserves morphology but overfixation may mask epitopes.

- Processing and embedding: Dehydrate through graded alcohols, clear in xylene, and embed in paraffin wax [1].

- Sectioning: Cut 3-5 μm sections using a microtome and mount on charged slides [2].

Staining Procedure:

- Deparaffinization and rehydration: Heat slides at 60°C for 30 minutes, followed by xylene and graded alcohol series [1].

- Antigen retrieval: Heat slides in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) or EDTA buffer (pH 8.0) using a pressure cooker, microwave, or steamer for 20 minutes [1] [2]. This step reverses formaldehyde-induced cross-links that mask epitopes.

- Endogenous enzyme blockade: Incubate with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 minutes to quench endogenous peroxidase activity [1].

- Blocking: Apply 5-10% normal serum from secondary antibody host species for 30 minutes to reduce non-specific binding [2].

- Primary antibody incubation: Apply optimized antibody dilution in antibody diluent and incubate overnight at 4°C in a humidity chamber [2].

- Secondary antibody application: Apply species-specific secondary antibody conjugated to HRP or AP for 30-60 minutes at room temperature [7].

- Chromogen development: Incubate with DAB (brown precipitate) or AEC (red precipitate) substrate until desired intensity [7].

- Counterstaining: Apply hematoxylin for 1-2 minutes to visualize nuclei [1].

- Dehydration and mounting: Dehydrate through graded alcohols, clear in xylene, and mount with permanent medium [1].

Detailed Western Blot Protocol

Sample Preparation:

- Cell lysis: Use RIPA buffer (for whole cell extracts) or NP-40 buffer (for cytoplasmic proteins) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors [3] [4]. Maintain samples on ice throughout.

- Protein quantification: Perform BCA or Bradford assay to determine protein concentration [3].

- Sample denaturation: Mix lysate with Laemmli buffer containing DTT or β-mercaptoethanol, then heat at 95°C for 5 minutes [3].

Electrophoresis and Transfer:

- Gel electrophoresis: Load 20-40 μg protein per well on SDS-PAGE gel (8-16% acrylamide depending on protein size) and run at 100-150V until dye front reaches bottom [3] [4].

- Protein transfer: Transfer proteins to nitrocellulose or PVDF membrane using wet or semi-dry transfer systems [4].

Immunodetection:

- Blocking: Incubate membrane in 5% non-fat milk or BSA in TBST for 1 hour at room temperature [3] [4].

- Primary antibody incubation: Incubate with optimized antibody dilution in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C [3].

- Secondary antibody incubation: Apply HRP or fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature [3].

- Signal detection: For chemiluminescence, incubate with ECL substrate and expose to film or digital imager [3] [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of either technique requires carefully selected reagents and appropriate controls to ensure specificity and reproducibility.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for IHC and Western Blot

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Fixatives | 10% neutral buffered formalin, 4% PFA, ethanol, methanol [1] [2] | Preserve tissue architecture and prevent degradation; impact epitope availability |

| Antigen Retrieval Reagents | Citrate buffer (pH 6.0), EDTA/EGTA buffer (pH 8.0-9.0) [1] | Reverse formaldehyde cross-links; critical for FFPE tissue epitope exposure |

| Blocking Agents | Normal serum, BSA, non-fat dry milk [2] [3] | Reduce non-specific antibody binding and background signal |

| Detection Systems | HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies, ABC kit, polymer-based systems [7] | Amplify signal and enable target visualization; impact sensitivity |

| Protease Inhibitors | PMSF, aprotinin, leupeptin, EDTA [3] | Prevent protein degradation during sample preparation |

| Protein Assays | BCA, Bradford, Lowry assay [3] | Quantify protein concentration for equal loading |

| Validation Controls | Knockout tissues/cells, isotype controls, positive control tissues [8] [9] | Verify antibody specificity and experimental reliability |

Technical Challenges and Troubleshooting

Common Pitfalls and Solutions

IHC-Specific Issues:

- High background staining: Often caused by inadequate blocking, overfixation, or endogenous enzyme activity. Solution: Optimize blocking conditions and implement appropriate quenching steps [1].

- Weak or absent signal: May result from insufficient antigen retrieval, antibody concentration too low, or overfixation. Solution: Titrate antibodies and optimize retrieval methods [1] [2].

- Non-specific staining: Frequently due to antibody cross-reactivity. Solution: Include appropriate negative controls and validate antibodies with knockout tissues [8].

Western Blot-Specific Issues:

- Non-specific bands: Often caused by antibody cross-reactivity or incomplete blocking. Solution: Use more stringent blocking conditions and validate antibodies [4] [9].

- High background: Typically results from insufficient washing or membrane drying. Solution: Increase wash frequency and volume [3].

- No signal: May be due to transfer issues, inappropriate antibody dilution, or protein degradation. Solution: Verify transfer efficiency with Ponceau S staining and titrate antibodies [3].

Antibody Validation Concerns

A significant challenge in both techniques is antibody specificity. Studies have shown that many commercial antibodies lack sufficient validation, with one analysis of Tau antibodies revealing that over half showed non-specific binding to other proteins [8]. Similarly, issues with tissue factor antibodies have been reported, where commonly used antibodies failed to detect the target in mouse models [9].

Validation Recommendations:

- Use genetic controls (knockout cells or tissues) when possible [8] [9]

- Compare multiple antibodies against non-overlapping epitopes [8]

- Verify expected molecular weight and cellular localization patterns [4]

- Utilize orthogonal methods to confirm findings [9]

Future Perspectives and Technological Advances

Both IHC and Western blotting continue to evolve with technological advancements:

IHC Innovations:

- Digital pathology and AI: Automated image analysis algorithms are reducing subjectivity in interpretation [1]

- Multiplexing technologies: Methods like multiplexed ion beam imaging (MIBI) and cyclic immunofluorescence enable detection of dozens of markers simultaneously [1]

- Enhanced signal amplification: Novel polymer-based systems continue to improve sensitivity [7]

Western Blot Advancements:

- Capillary electrophoresis: Systems like Protein Simple's Jess allow automated, quantitative western blotting with reduced sample handling [4]

- Single-cell western blot: Enables protein analysis at single-cell resolution [4]

- Improved quantification: Fluorescent detection methods with linear dynamic ranges facilitate more accurate quantification [3] [5]

IHC and Western blot, while sharing the fundamental principle of antibody-antigen specificity, serve complementary roles in protein detection and analysis. IHC excels in providing spatial context within tissues, making it indispensable for diagnostic pathology and morphological correlation. Western blot offers superior capabilities for protein size determination and semi-quantitative analysis of expression levels. The choice between these techniques should be guided by the specific research question, with many studies benefiting from employing both methods to obtain comprehensive protein characterization. As antibody validation remains a critical concern for both techniques, rigorous controls and verification of specificity are essential for generating reliable, reproducible data in both research and diagnostic applications.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and Western blot (WB) are foundational techniques in protein detection that exploit the specific binding of antibodies to their target antigens. Despite this shared principle, they represent two fundamentally different philosophies in experimental approach: tissue preservation versus protein separation [6].

IHC is designed to provide spatial context within intact tissue architecture, allowing researchers to visualize protein distribution within specific cells and subcellular compartments in their morphological context [2]. In contrast, Western blot emphasizes molecular separation, breaking down tissues to separate proteins by molecular weight for quantitative analysis [10]. This fundamental difference in philosophy dictates their respective workflows, applications, and the type of data they generate.

The historical development of these techniques reflects their distinct purposes. IHC traces its origins to the early 1940s when Albert H. Coons developed fluorescently conjugated antibodies to detect bacteria within macrophages [2]. Western blot emerged later, first described by Dr. Burnette in 1981 as an adaptation of the Southern blot for DNA and Northern blot for RNA [10].

Technical Workflows: From Sample to Signal

Immunohistochemistry Workflow

IHC Workflow Diagram Title: IHC Tissue Preservation Pathway

IHC begins with tissue fixation using formaldehyde-based fixatives like formalin or paraformaldehyde, which create methylene cross-links between proteins to preserve tissue integrity and morphology [2]. Fixed tissues are then embedded in paraffin wax and sectioned into thin slices (3-5 μm) placed on slides [6]. A critical antigen retrieval step follows, where heat-induced epitope retrieval reverses formaldehyde-induced cross-links that may mask target epitopes [2]. After blocking to prevent non-specific antibody binding, samples undergo sequential incubation with primary antibodies (either monoclonal or polyclonal) specific to the target antigen, followed by secondary antibodies conjugated to enzymes (e.g., HRP) or fluorophores [6]. Finally, counterstaining with dyes like hematoxylin (for nuclei) or eosin (for cytoplasm) provides morphological context, with visualization via microscopy [11].

Western Blot Workflow

Western Blot Workflow Diagram Title: WB Protein Separation Pathway

Western blot starts with protein extraction using cell lysis buffers containing detergents (e.g., NP-40, Triton X-100) and protease/phosphatase inhibitors to maintain protein integrity [12]. The extracted protein concentration is precisely measured using colorimetric assays like Bradford or BCA, then denatured in Laemmli buffer containing SDS and β-mercaptoethanol to linearize proteins and mask their intrinsic charge [10]. SDS-PAGE electrophoresis separates proteins solely by molecular weight as they migrate through a polyacrylamide gel matrix [10]. Separated proteins are then transferred to a membrane (nitrocellulose or PVDF) via electrophoresis [10]. Similar to IHC, the membrane is blocked, incubated with primary and secondary antibodies, and detected using chemiluminescent, colorimetric, or fluorescent methods [6] [12].

Comparative Analysis: Technical Specifications and Performance

Table 1: Direct Comparison of IHC and Western Blot Characteristics

| Parameter | Immunohistochemistry (IHC) | Western Blot |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Type | Intact tissue sections (3-5 μm) | Protein extracts from lysed cells/tissues |

| Protein State | In situ, fixed | Denatured, linearized |

| Separation Basis | Cellular and subcellular localization | Molecular weight |

| Detection Method | Chromogenic (DAB) or fluorescent | Chemiluminescent, fluorescent, or colorimetric |

| Data Output | Spatial distribution within morphology | Molecular weight with quantitative potential |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Up to 4 targets with careful panel design | Multiple targets per blot (limited by antibody compatibility) |

| Throughput | Medium | Low to medium |

| Key Advantage | Preserves tissue architecture and location | Confirms target identity by molecular weight |

Quantitative Performance and Detection Limits

Table 2: Quantitative Performance and Validation Approaches

| Aspect | Immunohistochemistry | Western Blot |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative Capacity | Semi-quantitative; novel qIHC methods emerging [13] | Principally quantitative with proper validation [14] |

| Linear Range | Limited dynamic range | 8-fold to two orders of magnitude when validated [14] |

| Detection Specificity | Spatial pattern within tissue context; requires counterstains for orientation [11] | Molecular weight confirmation via ladder comparison [6] |

| Validation Controls | Tissue known to express/not express target; no-primary antibody control; isotype controls [15] | Knockout/knockdown lysates; positive control lysates; no-primary antibody control [16] |

| Loading Controls | Not applicable | Housekeeping proteins (β-actin, GAPDH); total protein staining [15] [12] |

Advantages and Limitations in Research Applications

IHC excels in diagnostic pathology and when investigating protein localization patterns within complex tissues. Its ability to preserve morphological context makes it indispensable for cancer diagnostics, where abnormal cellular patterns are visually apparent [6]. However, IHC has limitations in quantification precision and cannot confirm target identity by molecular weight, potentially leading to false positives from non-specific binding [6].

Western blot provides molecular weight verification, which serves as an additional specificity check. Recent studies demonstrate that properly validated antibodies can achieve excellent quantitative performance with linear ranges spanning up to two orders of magnitude [14]. The technique also allows for simultaneous detection of multiple targets when carefully designed. However, Western blot loses all spatial and subcellular localization information and requires protein denaturation, which may destroy some conformational epitopes [6].

Experimental Design: Controls and Validation

Essential Controls for Reliable Results

IHC Controls:

- Positive tissue controls: Tissues known to express the target protein [15]

- Negative tissue controls: Tissues known not to express the target protein [15]

- No-primary antibody controls: Assess non-specific secondary antibody binding [15]

- Isotype controls: Non-immune antibodies matching primary antibody isotype [15]

- Absorption controls: Primary antibody pre-absorbed with immunogen [15]

Western Blot Controls:

- Positive control lysates: Cell lines or tissues known to express the target protein [15]

- Negative control lysates: Knockout/knockdown cell lines or tissues lacking the target [15] [16]

- No-primary antibody controls: Assess secondary antibody specificity [15]

- Loading controls: Housekeeping proteins (β-actin, GAPDH) or total protein stains [15] [12]

- Molecular weight markers: Verify target size matches expected molecular weight [10]

Antibody Validation Strategies

Both techniques require rigorous antibody validation, preferably using a binary approach that tests antibodies in biologically relevant positive and negative expression systems [16]. Genetic knockout models (CRISPR, siRNA) provide ideal negative controls, while treatments that induce target expression or modification can serve as positive controls [16]. Critically, antibodies must be validated separately for each application, as performance in one technique doesn't guarantee specificity in another [16].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Their Functions

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Fixation Agents | Formalin, Paraformaldehyde, Ethanol, Methanol | Preserve tissue architecture and prevent degradation [2] |

| Antigen Retrieval Reagents | Citrate buffer, EDTA, Tris-EDTA | Reverse formaldehyde cross-links to expose epitopes [2] |

| Counterstains | Hematoxylin, Eosin, DAPI, Nuclear Fast Red | Provide morphological context and contrast to primary signal [11] |

| Protein Lysis Buffers | RIPA buffer, NP-40 buffer | Extract proteins while maintaining integrity for WB [12] |

| Gel Electrophoresis Reagents | Acrylamide, Bis-acrylamide, SDS, Tris buffers | Create molecular sieve for protein separation by size [10] |

| Blocking Agents | BSA, non-fat milk, casein | Reduce non-specific antibody binding [12] |

| Detection Substrates | DAB, Enhanced chemiluminescence, Fluorescent tags | Generate detectable signal from antibody-antigen complexes [6] |

The choice between IHC and Western blot ultimately depends on the research question. IHC is unequivocally superior when spatial context, cell-specific expression patterns, or tissue morphology are relevant to the biological hypothesis. It remains the technique of choice for clinical diagnostics, tumor classification, and subcellular localization studies.

Western blot provides critical advantages when molecular weight confirmation, quantitative precision, or post-translational modification detection are prioritized. It excels in signaling pathway analysis, protein expression quantification, and validation of genetic manipulations.

Increasingly, these techniques are used complementarily, with Western blot validating antibody specificity and providing quantitative framework, while IHC places these findings in their proper biological context. This integrated approach leverages the respective strengths of both techniques while mitigating their individual limitations, providing a more comprehensive understanding of protein expression and function in health and disease.

In the fields of cell biology and biomedical research, immunohistochemistry (IHC) and Western blot (WB) stand as two foundational techniques for protein detection. Despite sharing a common principle—exploiting the specific binding of antibodies to target antigens—they provide fundamentally different types of information [6]. IHC excels at visualizing the precise spatial localization of proteins within the context of intact tissue architecture, typically using chromogenic or fluorescent detection [2] [17]. In contrast, Western blot is unparalleled in its ability to confirm a protein's molecular weight and provide semi-quantitative data on its expression levels in a complex mixture [10] [4]. This guide offers an objective comparison of these two techniques, detailing their respective performances, optimal applications, and underlying protocols to inform research and development decisions.

Core Principle Comparison: Spatial Context vs. Molecular Size

The fundamental divergence between IHC and Western blot lies in their starting material and the primary information they deliver.

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC) preserves the tissue's structural integrity. Proteins are detected in situ within fixed tissue sections, allowing researchers to see which cells express the protein, its subcellular compartment (e.g., nucleus, cytoplasm, membrane), and its distribution patterns across a heterogeneous tissue sample [2] [17]. This makes IHC an indispensable tool for pathology and developmental biology.

- Western Blot (WB) begins with a homogenized tissue or cell lysate, destroying all spatial context. Proteins are denatured, separated by molecular weight via gel electrophoresis, and then transferred to a membrane for antibody probing [10] [4]. Its key strength is confirming a protein's identity based on its size and providing a semi-quantitative measure of its abundance.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of IHC and Western Blot

| Feature | Immunohistochemistry (IHC) | Western Blot (WB) |

|---|---|---|

| Protein State | In situ, within intact tissue/cells [2] | Denatured [10] |

| Primary Output | Protein localization and spatial distribution [17] | Molecular weight confirmation and semi-quantification [4] |

| Tissue/Cellular Context | Preserved | Destroyed |

| Key Advantage | Visualizes protein expression in complex tissues and different cell types [2] | Verifies protein identity via size; can detect post-translational modifications [4] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Easily multiplex 2-4 targets with fluorescent detection [18] | Possible with fluorescent probes, but more limited [17] |

Performance and Experimental Data Analysis

The performance of IHC and Western blot must be evaluated against different metrics, as they are designed to answer distinct biological questions.

Antibody Performance is Context-Dependent

A critical consideration is that an antibody's performance is highly application-specific. A study analyzing 13,000 antibodies found that while 45% yielded supportive staining in Western blot, 43% showed bands of the wrong size, indicating potential cross-reactivity or non-specificity [19]. Importantly, the study demonstrated that antibody performance does not directly translate between applications; an antibody that works well in Western blot may not be effective for IHC and vice versa [19]. This underscores the necessity of using antibodies validated for the specific application.

Detection Limits and Specificity

Western blot generally offers high specificity because the combination of separation by molecular weight and antibody binding provides two layers of validation [2]. If a band appears at the expected size, it strongly supports the correct identification of the target protein. IHC, while providing exquisite localization, lacks this internal size check. The staining pattern is taken as evidence for the target's presence, but without the molecular weight confirmation, there is a risk of misinterpreting non-specific or cross-reactive staining [6].

Table 2: Performance and Validation Metrics

| Performance Metric | Immunohistochemistry (IHC) | Western Blot (WB) |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Medium; can be enhanced with signal amplification (e.g., polymer-based methods) [18] | High; can detect very small quantities of protein [17] |

| Specificity | Medium; relies solely on antibody specificity without molecular weight confirmation [2] | High; confirmation via molecular weight increases confidence [6] |

| Quantification | Semi-quantitative at best [2] | Semi-quantitative; good for comparing relative levels between samples [4] |

| Key Validation | Colocalization with known cellular markers | Coincidence with expected molecular weight on the blot |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) Workflow

The IHC protocol aims to preserve tissue morphology while making the target antigen accessible for antibody binding.

- Sample Preparation and Fixation: Tissue is collected and fixed immediately, most commonly with formaldehyde-based fixatives like formalin or paraformaldehyde. This step preserves tissue architecture and prevents degradation [2]. The tissue is then embedded in paraffin and thinly sectioned, or frozen and sectioned for cryostat use.

- Antigen Retrieval: For formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues, a crucial antigen retrieval step is often required. Heat-induced epitope retrieval (HIER) using a buffer solution breaks the methylene cross-links formed during fixation, which can mask epitopes and reduce antibody binding [2].

- Blocking and Antibody Incubation: Sections are incubated with a blocking serum to reduce non-specific background staining. This is followed by incubation with the primary antibody specific to the target protein. An enzyme-conjugated (e.g., HRP) or fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody is then applied [2] [18].

- Detection and Visualization:

- Chromogenic Detection: An enzyme substrate (e.g., DAB for HRP) is added, which produces an insoluble colored precipitate at the site of the target antigen. The staining can be observed with a standard light microscope [20] [18].

- Fluorescent Detection: The fluorophore is directly excited by light of a specific wavelength, and the emitted light is detected using a fluorescence microscope. This allows for multiplexing by using antibodies conjugated to different fluorophores [20] [18].

IHC Experimental Workflow

Western Blot (WB) Workflow

The Western blot protocol is designed to separate proteins by size and then specifically detect a target within the complex mixture.

- Sample Preparation: Cells or tissues are lysed using a detergent-based lysis buffer. Protease and phosphatase inhibitors are added to prevent protein degradation. The total protein concentration of each sample is measured (e.g., via Bradford assay) and normalized to ensure equal loading across the gel [10] [4].

- Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE): The normalized protein samples are mixed with Laemmli buffer, which contains SDS to denature proteins and give them a uniform negative charge, and a reducing agent to break disulfide bonds. The samples are then loaded onto a polyacrylamide gel. An electric current is applied, causing proteins to migrate through the gel matrix and separate strictly by their molecular weight [10].

- Electrophoretic Transfer (Blotting): The separated proteins are transferred from the gel onto a membrane (typically nitrocellulose or PVDF) using an electric current. This creates a replica of the gel's protein pattern on the membrane [10].

- Blocking and Antibody Probing: The membrane is incubated in a blocking solution (e.g., non-fat milk or BSA) to prevent non-specific antibody binding. It is then probed sequentially with a primary antibody against the target protein and an enzyme-conjugated (e.g., HRP) secondary antibody [10] [4].

- Detection: A chemiluminescent substrate for HRP is added to the membrane. The enzyme catalyzes a light-producing reaction, which is captured by a digital imager. The resulting band's position is compared to a molecular weight ladder, confirming the target protein's size, and the band intensity can be used for semi-quantitative analysis [17] [4].

Western Blot Experimental Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of IHC and Western blot relies on a suite of critical reagents. The table below details essential materials and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for IHC and Western Blot

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixatives | Formalin, Paraformaldehyde [2] | Preserves tissue architecture and antigenicity by creating protein cross-links. | IHC |

| Embedding Media | Paraffin wax, Cryomedia/OCT [2] | Provides structural support for thin sectioning of tissues. | IHC |

| Lysis Buffers | RIPA Buffer [10] | Breaks open cells and solubilizes proteins for extraction. | WB |

| Protease Inhibitors | Cocktails (e.g., PMSF) [10] | Prevents protein degradation by endogenous proteases during sample prep. | WB |

| Gel Components | Acrylamide, Bis-acrylamide [10] | Forms the porous gel matrix for size-based protein separation. | WB |

| Membranes | Nitrocellulose, PVDF [10] | Binds proteins after transfer for antibody probing. | WB |

| Primary Antibodies | Monoclonal, Polyclonal [19] | Binds specifically to the target protein of interest. | IHC, WB |

| Detection Enzymes | Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) [18] | Conjugated to secondary antibody; catalyzes signal production. | IHC, WB |

| Chromogenic Substrates | DAB (brown), AEC (red) [18] | Enzyme converts this to an insoluble colored precipitate. | IHC |

| Chemiluminescent Substrates | Luminol-based reagents [4] | Enzyme converts this to a light signal for digital imaging. | WB |

| Fluorophores | Alexa Fluor dyes [18] | Emits light at a specific wavelength when excited. | IHC (IF) |

IHC and Western blot are complementary, not competing, techniques in the protein detection arsenal. The choice between them is dictated by the research question.

- Choose Immunohistochemistry (IHC) when the primary goal is to understand the spatial distribution, cellular context, and subcellular localization of a protein within a complex tissue. It is the preferred method for diagnostic pathology, tumor marker identification, and developmental biology studies [6] [17].

- Choose Western Blot (WB) when the goals are to confirm a protein's identity based on its molecular weight, obtain semi-quantitative data on its expression levels across different samples, or detect specific post-translational modifications that alter molecular weight [4].

For the most robust conclusions, particularly when working with a new antibody or an uncharacterized protein, the combined use of both techniques is highly powerful. Western blot can verify the antibody's specificity and the protein's size, while IHC can then be used with greater confidence to reveal the protein's precise location within the tissue.

Inherent Strengths and Limitations of Each Technique

In the fields of molecular biology and biomedical research, protein detection techniques are fundamental tools for understanding cellular function, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic development. Among the most established methods are Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and Western blotting, both leveraging the specific binding of antibodies to target antigens [6]. Despite this shared principle, each technique offers distinct capabilities and suffers from unique constraints that directly influence their application in research and diagnostics. IHC provides spatial context within tissue architecture, preserving morphological information that is destroyed by Western blot's requirement for tissue homogenization [1] [6]. Conversely, Western blot excels at providing molecular weight confirmation and semi-quantitative data about protein expression levels, advantages not inherent to standard IHC protocols [6] [4]. This article objectively compares the technical performance, applications, and limitations of IHC and Western blot to guide researchers in selecting the appropriate method for their specific experimental questions.

Fundamental Principles and Workflows

The core difference between IHC and Western blot lies in their treatment of the sample and the consequent information they can deliver. Understanding their fundamental workflows is essential for appreciating their respective strengths and limitations.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) Workflow

IHC is designed to visualize the precise localization and distribution of antigens within intact tissue structures [1]. The process begins with tissue collection followed by chemical fixation—typically using formaldehyde-based fixatives—to preserve tissue architecture and prevent degradation [1] [2]. Fixed tissues are then embedded in paraffin or optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound and sectioned into thin slices (3-5 µm) using a microtome or cryostat [2]. These sections are mounted on slides and may undergo antigen retrieval to reverse the cross-links formed during formalin fixation, which can mask epitopes and reduce antibody binding [1] [2]. Subsequent steps include blocking to prevent non-specific antibody binding, incubation with a primary antibody specific to the target antigen, and detection using enzyme-conjugated (e.g., HRP) or fluorescently-labeled secondary antibodies [1]. Finally, the stained tissues are visualized under a light or fluorescence microscope, allowing researchers to assess protein expression within specific cell types and subcellular compartments [1] [6].

Figure 1: IHC Workflow. The process preserves tissue architecture through fixation and thin sectioning, enabling spatial protein localization.

Western Blot Workflow

Western blot, in contrast, analyzes proteins from homogenized tissue or cell lysates, sacrificing spatial information for the ability to separate proteins by molecular weight [4] [10]. The initial step involves sample preparation using denaturing lysis buffers containing detergents like SDS and reducing agents such as DTT or β-mercaptoethanol to disrupt protein structures and break disulfide bonds [3] [10]. The protein concentration of the lysate is quantified using assays like Bradford or BCA to ensure equal loading across gels [10]. Proteins are then separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), which resolves complex protein mixtures into discrete bands based on molecular weight [10]. The separated proteins are subsequently transferred (blotted) onto a membrane, typically nitrocellulose or PVDF, creating an replica of the gel [4] [10]. The membrane is blocked to prevent non-specific antibody binding and then probed with a primary antibody against the protein of interest, followed by an enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody [10]. Detection is achieved through chemiluminescent or fluorescent substrates, generating a signal that corresponds to the abundance of the target protein at its specific molecular weight [3] [10].

Figure 2: Western Blot Workflow. The process involves tissue/cell homogenization, protein separation by size, and transfer to a membrane for detection.

Comparative Analysis: Strengths and Limitations

The distinct methodologies of IHC and Western blot endow each technique with a unique profile of advantages and disadvantages. The table below provides a structured comparison of their inherent strengths and limitations.

Table 1: Direct comparison of IHC and Western blot techniques

| Parameter | Immunohistochemistry (IHC) | Western Blot |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | High - Preserves tissue morphology and enables subcellular localization [1] [6] | None - Proteins are homogenized; no spatial information retained [6] |

| Quantitative Capability | Semi-quantitative at best - Subjective scoring (intensity, distribution); limited dynamic range [1] | Semi-quantitative/Quantitative - Densitometry allows for relative quantification between samples [4] [10] |

| Specificity & Validation | Lower - Staining is not checked against molecular weight; risk of off-target binding [6] | Higher - Size separation confirms target identity via molecular weight [6] [8] |

| Throughput & Automation | Moderate - Automated staining systems available (e.g., Tissue-Tek Genie) [21] | Moderate - Capillary electrophoresis systems enable automation [4] |

| Multiplexing Potential | Easily up to 4 targets; more possible with specialized unmixing [2] | Possible with fluorescent multiplexing or sequential blotting [2] |

| Sensitivity | Medium - Capable of detecting low abundance proteins in a localized context [2] | High - Can detect low abundance proteins, especially with prior enrichment [2] [3] |

| Sample Integrity | Analyzes proteins in their natural, fixed state [1] | Proteins are denatured and reduced; native state is lost [10] |

| Key Diagnostic Applications | Cancer subtyping, infectious disease identification, neurodegenerative disease diagnosis [1] [21] | HIV confirmatory testing, autoimmune disease diagnosis, BSE (prion disease) [6] [10] |

Key Strengths and Limitations Elaborated

Spatial Information vs. Molecular Weight Confirmation: The most significant trade-off lies between IHC's ability to localize proteins within a tissue context and Western blot's capacity to confirm a protein's identity based on its size. IHC is unparalleled for determining whether a protein is expressed in a specific cell type, its subcellular localization (nuclear, cytoplasmic, membrane), and its distribution pattern across a tissue section [1] [6]. This is critical in pathology for identifying tumor margins or characterizing the microenvironment. Western blot, however, provides an essential control for antibody specificity because the target protein should appear as a band at its expected molecular weight. This helps distinguish the actual protein from non-specific signals or proteolytic fragments, a validation not inherent to IHC [6] [8].

Quantitative Analysis and Dynamic Range: Western blot has a clear advantage in semi-quantification. Using densitometric analysis of band intensity, researchers can compare relative protein levels across different samples (e.g., treated vs. untreated) or assess post-translational modifications when combined with phospho-specific antibodies [4] [10]. The linear range of detection depends on the method but is generally broader than IHC. In contrast, IHC quantification is typically semi-quantitative, relying on scoring systems that categorize staining intensity (e.g., 0, 1+, 2+, 3+) and the percentage of positive cells [1]. This scoring is subjective and prone to inter-observer variability, though digital pathology and AI are emerging to address this limitation [1].

Sensitivity and Specificity Challenges: Both techniques are susceptible to antibody-related issues, a major contributor to the reproducibility crisis in science. A 2024 study systematically validating Tau antibodies found that performance is highly application-specific; many antibodies that worked well in Western blot failed in IHC and vice versa [8]. Over half of the Tau antibodies tested by Western blot showed non-specific binding to other proteins, while others failed to detect the target at endogenous levels [8]. This underscores the critical need for rigorous antibody validation for each specific application.

Experimental Data and Validation

Empirical data highlights the practical performance differences and complementarity of IHC and Western blot. A systematic investigation of 79 Tau antibodies for Western blot and 35 for IHC revealed critical application-specific performance issues [8]. While most antibodies detected overexpressed Tau, many failed at lower, physiological concentrations. Furthermore, over 50% of antibodies tested by Western blot showed non-specific binding to other proteins, and phosphorylation of Tau residues partially inhibited binding for many "total" Tau antibodies, including the popular Tau-5 clone [8]. This study underscores that antibody performance is context-dependent and that rigorous validation for each specific technique is paramount for reliable results.

Table 2: Key research reagents for IHC and Western blot analysis

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Formaldehyde/PFA | Crosslinking fixative for IHC | Preserves tissue structure; can mask epitopes, often requiring antigen retrieval [2] |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denaturing detergent for Western blot | Coats proteins with negative charge, allowing separation by molecular weight [10] |

| Primary Antibodies | Bind specifically to target antigen | Must be validated for the specific application (IHC or WB); clones perform differently [8] |

| HRP-Conjugated Secondary Antibodies | Detect bound primary antibodies | Enable enzymatic (DAB) or chemiluminescent detection in both techniques [1] [10] |

| Antigen Retrieval Buffers | Reverse formaldehyde cross-links | Critical for recovering antigenicity in FFPE tissues for IHC [1] |

| Protease & Phosphatase Inhibitors | Added to Western blot lysis buffers | Prevent protein degradation and maintain phosphorylation states during sample prep [3] [10] |

| Blocking Reagents (BSA, Non-fat Milk) | Reduce non-specific background | BSA is preferred for phospho-specific antibodies in WB due to casein in milk [10] |

| PVDF/Nitrocellulose Membranes | Immobilize proteins for Western blot | PVDF offers higher protein binding capacity and chemical resistance [10] |

IHC and Western blot are complementary, not interchangeable, techniques in the protein detection arsenal. The choice between them should be dictated by the specific research question. IHC is the superior technique when the experimental goal requires understanding the spatial distribution and cellular context of protein expression, such as in diagnostic pathology, characterizing tumor heterogeneity, or mapping protein expression in complex tissues like the brain [1] [6]. Western blot is the more appropriate method when the objectives include confirming a protein's identity based on molecular weight, obtaining semi-quantitative data on expression levels, or detecting specific proteoforms and post-translational modifications [4] [10]. For the most comprehensive analysis, particularly when investigating novel proteins or using unvalidated antibodies, employing both techniques in parallel can provide a more robust and validated dataset. IHC can reveal the biological context of expression, while Western blot can confirm the specificity of the detection and offer quantitative insights, together providing a more complete understanding of protein expression and function.

Methodology in Action: Choosing the Right Technique for Your Research Goal

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) stands as a cornerstone technique in molecular biology, combining principles from histology, immunology, and biochemistry to detect specific antigens or proteins within tissue samples while preserving their spatial context [22]. Unlike other protein detection methods like western blotting or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) that require tissue homogenization, IHC offers the unique advantage of precisely locating target proteins within intact tissue architecture without digestion [22]. This spatial preservation makes IHC indispensable for both clinical diagnostics and research, particularly in the analysis of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues - the gold standard for surgical and pathological sample preservation worldwide [23] [22].

The extensive collections of FFPE samples in biobanks and pathology archives represent an invaluable yet underutilized resource for human biology and translational research [23]. Recent advances in spatial biology have further amplified IHC's importance, enabling researchers to visualize and quantify proteins exactly where cells produce and use them within complex tissues like the brain, where cellular heterogeneity and regional specialization play crucial roles in function [24]. This guide examines the complete IHC workflow for FFPE tissues, objectively compares its performance with western blotting, and explores emerging spatial multi-omics approaches that integrate protein localization with transcriptomic data.

Core Technique Comparison: IHC vs. Western Blot

Fundamental Principles and Applications

Table 1: Core Characteristics of IHC and Western Blot

| Characteristic | Immunohistochemistry (IHC) | Western Blotting |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Context | Preserved - enables protein localization within tissue architecture | Destroyed - requires tissue homogenization |

| Protein Detection | Visualized in situ without digestion [22] | Requires protein extraction and denaturation |

| Primary Output | Protein localization and distribution patterns | Relative protein quantity and molecular weight |

| Tissue Requirements | FFPE or frozen sections [22] | Homogenized cell or tissue lysates [4] |

| Key Applications | Diagnostic pathology, spatial biology, cell typing [22] | Protein expression quantification, post-translational modification detection [4] |

| Advantages | Maintains tissue morphology, clinical relevance | Provides size information, semi-quantitative data [4] |

| Limitations | Semi-quantitative, subjective interpretation [22] | Loses spatial information, more complex sample prep [4] |

Technical Performance and Data Output

Table 2: Technical Comparison of Protein Detection Methods

| Performance Metric | IHC | Western Blot | ELISA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | High (single-cell detection possible) | Moderate to high [4] | High |

| Specificity | Dependent on antibody validation [25] | Dependent on antibody validation [4] | High |

| Quantification Capability | Semi-quantitative (scoring systems) [22] | Semi-quantitative to quantitative [4] | Fully quantitative |

| Molecular Weight Information | No | Yes - key advantage [4] | No |

| Multiplexing Potential | Moderate (recent advances to 8+ markers) [24] [26] | Low (typically single-plex) | Moderate |

| Throughput | Moderate to high (TMAs) [26] | Low to moderate [4] | High |

| Equipment Requirements | Standard microscopy (light or fluorescence) [22] | Electrophoresis and transfer systems [4] | Plate reader |

Western blotting provides critical information about protein size that IHC cannot offer, making it preferable for confirming the identity of specific protein isoforms or detecting cleavage products [4]. However, IHC's preservation of spatial context makes it indispensable for understanding tissue heterogeneity and cellular organization in both healthy and disease states [22].

The Complete IHC Workflow for FFPE Tissues

Sample Preparation and Fixation

The IHC workflow begins with proper tissue handling and fixation, which are crucial steps for preserving cellular integrity and preventing degradation during sample processing [22]. For FFPE tissues, chemical fixation - typically with 10% neutral buffered formalin - stabilizes cells and tissues while preserving morphological detail for diagnosis and specialized testing [22]. Effective fixation requires adequate sample size and sufficient fixative volume to ensure thorough penetration [22]. Following fixation, tissues undergo dehydration through increasing ethanol concentrations, clearing in xylene, and embedding in paraffin wax to create blocks that can be stored for decades and sectioned for analysis [23] [22].

Critical Protocol Steps and Optimization

Deparaffinization and Antigen Retrieval

For FFPE tissues, sections must be deparaffinized through heating at 60°C for 20 minutes followed by submersion in xylene for 15 minutes, then rehydrated through a graded ethanol series (100% to 50%) [26]. Antigen retrieval is crucial for reversing formaldehyde-induced crosslinks that obscure epitopes. Two main approaches exist:

- Heat-induced epitope retrieval (HIER): Using Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 9.0) at 65°C overnight, or citrate buffer (pH 6.0) [23] [26]

- Proteolytic-induced epitope retrieval (PIER): Utilizing proteinase K or pepsin treatments [23]

Recent spatial FFPE-ATAC-seq research has demonstrated that optimal retrieval conditions using Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 9.0) at 65°C with proteinase K digestion (10 ng/μl for 45 minutes) significantly improve biomolecule accessibility while preserving tissue architecture [23].

Blocking and Antibody Incubation

Non-specific binding is minimized through blocking with proteins like bovine serum albumin (BSA) at 2-5% concentration, normal serum, or commercial blocking buffers [27]. BSA's chemical inertness, high solubility, and low cross-reactivity make it particularly effective for blocking unoccupied surfaces while maintaining antibody stability [27]. Primary antibody incubation typically occurs overnight at 4°C in a moist chamber, followed by species-appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated to enzymes (HRP or AP) or fluorophores [22] [26].

Detection and Counterstaining

Signal detection employs chromogenic substrates (DAB for brown, Fast Red for red) for brightfield microscopy or fluorophores (Alexa Fluor dyes) for fluorescence detection [24] [26]. Counterstaining with hematoxylin (for chromogenic) or DAPI (for fluorescent) provides structural context, helping antibody-stained cells "stand out more" and pinpointing their exact location in the tissue [27].

Advanced Spatial Multi-Omics: Integrating IHC with Transcriptomics

Dual RNA-Protein Detection Techniques

The integration of IHC with in situ hybridization (ISH) represents both a significant opportunity and technical challenge in spatial multi-omics [24]. This approach enables researchers to correlate gene expression patterns with protein abundance and localization in the same tissue section, providing unprecedented insights into coordinated molecular changes in normal development and disease [24]. However, standard IHC and ISH conditions directly conflict - IHC antibodies degrade during protease treatments that ISH requires, while RNases present during IHC protocols destroy RNA targets [24].

Recent protocol modifications successfully address these competing demands:

- RNase inhibition: Using recombinant ribonuclease inhibitors to preserve RNA during antibody incubation [24]

- Antibody crosslinking: Fixing antibodies to tissues after IHC labeling to protect protein signals during ISH pretreatments [24]

- Sequential detection: Careful optimization of detection order and conditions to preserve both biomolecules

These advances enable robust dual detection of both protein and mRNA targets in the same tissue section, as demonstrated in mouse brain studies successfully mapping both RNA (Gad2, Ppib) and protein (GFAP, HuC/HuD) markers in hippocampal regions [24].

High-Throughput and Automated IHC Approaches

Traditional IHC analysis has been limited by subjective manual assessment, inter-observer variability, and low throughput [26]. Recent advances in ImmunoHistoFluorescence (IHF) combine IF, automated microscopy, and AI-based image analysis to enable precise investigation of complex protein localization patterns in tissue samples at scale [26]. This approach overcomes previous limitations of tissue IF including limited antibody penetration, autofluorescence artifacts, and weak signals through optimized antigen retrieval, automated acquisition, and computational analysis [26].

Research Reagent Solutions and Experimental Materials

Essential Reagents for IHC Workflows

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for IHC Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Fixation Agents | 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin [22] | Preserves tissue architecture and antigen integrity |

| Antigen Retrieval Buffers | Tris-EDTA (pH 9.0), Citrate Buffer (pH 6.0) [23] | Reverses formaldehyde crosslinks, exposes epitopes |

| Blocking Agents | BSA (2-5%), Normal Serum, Non-fat Dry Milk [27] | Reduces non-specific antibody binding |

| Primary Antibodies | Validated monoclonal/polyclonal antibodies [25] | Specifically binds target antigens |

| Detection Systems | HRP-conjugated secondaries, Alexa Fluor dyes [24] [26] | Enables visualization of bound antibodies |

| Mounting Media | Fluoromount with DAPI [26] | Preserves samples and provides nuclear counterstain |

| Validation Tools | Knock-out cell lines, isotype controls [25] | Confirms antibody specificity and assay reliability |

Antibody Validation and Performance Considerations

Antibody quality remains a critical factor in IHC reproducibility and reliability. Independent validation studies comparing commercial antibodies across common applications reveal significant performance variations [25]. Recent comprehensive assessments show recombinant antibodies demonstrate up to 30% higher pass rates compared to polyclonal antibodies, with success rates of 97% for western blot, 55% for immunoprecipitation, and 83% for immunocytochemistry using standardized protocols [25]. These findings underscore the importance of using properly validated reagents, with recombinant antibodies offering superior consistency between batches due to their sequence-defined nature [25].

IHC and western blotting serve complementary roles in protein detection research. IHC excels when spatial context, cellular heterogeneity, and tissue architecture preservation are paramount, particularly for clinical diagnostics and spatial biology applications [22]. Western blotting remains preferable for protein quantification, molecular weight determination, and post-translational modification studies where spatial information is less critical [4]. The emerging integration of IHC with transcriptomic techniques through spatial multi-omics approaches represents a powerful frontier in biological research, enabling unprecedented correlation of protein localization with gene expression patterns in intact tissues [24]. As antibody validation efforts improve and spatial technologies advance, IHC will continue to evolve as an indispensable tool for bridging microscopic anatomy with molecular mechanisms in health and disease.

Western blotting remains a cornerstone technique in molecular biology and biochemistry for identifying and quantifying specific proteins within a complex mixture. This method combines the size-based separation power of gel electrophoresis with the specificity of antibody-based immunodetection, allowing researchers to analyze protein expression, post-translational modifications, and molecular weight. When compared alongside immunohistochemistry (IHC) for protein detection research, western blot provides complementary information; while IHC excels at visualizing protein localization within tissue architecture, western blot offers superior capabilities for determining molecular weight and semi-quantitative analysis of protein abundance [6] [28] [2]. The technique was first coined by Dr. Burnette in 1981 and has since evolved into a standardized protocol utilized across research and clinical laboratories worldwide [10].

A critical consideration in protein detection research is understanding that antibody performance is highly context-dependent [19] [29]. An antibody that performs well in western blot may not function adequately in IHC applications due to differences in protein conformation, target accessibility, and sample processing methods [19] [30]. This application-specific performance underscores the importance of technique selection based on research objectives and proper validation of reagents within the intended experimental context.

Western Blot Workflow: Step-by-Step Methodology

Stage 1: Sample Preparation and Protein Extraction

Proper sample preparation is fundamental for successful western blotting, as inadequate preparation can compromise subsequent steps and result in unreliable data [10] [31].

Cell Culture Lysate Preparation:

- Lysis Buffer Composition: Use appropriate lysis buffers such as RIPA buffer for total protein extraction or non-denaturing buffers for native proteins. Include protease inhibitor cocktails to prevent protein degradation and phosphatase inhibitors when studying phosphorylated proteins [31].

- Cell Processing: Wash suspension cells twice with PBS by centrifugation (100–500 × g, 5 min, 4°C) and resuspend in ice-cold lysis buffer. For adherent cells, detach mechanically or enzymatically before similar washing and resuspension [31].

- Lysis Protocol: Incubate cells in lysis buffer for 10 minutes at 4°C with rocking, followed by sonication to ensure complete cell disruption. Centrifuge at 14,000–17,000 × g for 5 minutes at 4°C to pellet insoluble debris, then transfer the supernatant (containing soluble proteins) to a fresh tube [31].

Tample Preparation:

- Rapidly dissect tissue with clean tools on ice to prevent protease degradation [31].

- Homogenize tissue samples using automated homogenizers with glass beads in lysis buffer (approximately 1,200 μL buffer per 200 mg tissue) for approximately 3 minutes at 4°C [31].

- Centrifuge homogenate at 14,000–17,000 × g for 5–10 minutes at 4°C and collect supernatant for analysis [31].

Protein Quantification and Normalization:

- Determine protein concentration using Bradford or BCA colorimetric assays against known protein standards [10] [31].

- Normalize samples to equal protein concentrations using cell lysis buffer, then add an equal volume of Laemmli sample buffer (1:1 ratio) [10].

- Laemmli buffer components serve specific functions: glycerol adds density for gel loading, bromophenol blue provides a visible dye front, SDS denatures proteins and imparts negative charge, beta-mercaptoethanol reduces disulfide bonds, and Tris-HCl buffers the system [10].

- Heat samples at 100°C for 10 minutes to fully denature proteins before loading [31].

Stage 2: Gel Electrophoresis and Protein Separation

Protein separation by molecular weight occurs through sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), which utilizes a discontinuous buffer system to achieve sharp protein bands [10].

Table 1: Gel Selection Guidelines Based on Protein Size

| Protein Size Range | Recommended Gel System | Running Buffer | Loading Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10–30 kDa | 4–12% acrylamide gradient Bis-Tris | MES | 10–40 μg lysate protein; 10–500 ng purified protein |

| 31–150 kDa | 4–12% acrylamide gradient Bis-Tris | MOPS | 10–40 μg lysate protein; 10–500 ng purified protein |

| >150 kDa | 3–8% acrylamide gradient Tris-Acetate | Tris-Acetate | 10–40 μg lysate protein; 10–500 ng purified protein |

| General purpose | 10–15% fixed-concentration Tris-Glycine | Tris-Glycine | 10–40 μg lysate protein; 10–500 ng purified protein |

Electrophoresis Procedure:

- Load equal protein quantities alongside molecular weight markers ("protein ladder") in adjacent lanes to enable molecular weight determination [10] [31].

- Apply electrical current to drive protein migration through the gel matrix. Smaller proteins migrate faster through the porous gel, while larger proteins migrate more slowly [10] [31].

- The Laemmli discontinuous buffer system uses a stacking gel with larger pores and acidic pH to concentrate proteins into a narrow band before they enter the resolving gel with smaller pores and basic pH where separation occurs [10].

- Run gels according to manufacturer recommendations, optimizing time and voltage based on the specific apparatus and target protein size [31].

Diagram 1: Complete Western Blot Workflow from Sample Preparation to Analysis

Stage 3: Protein Transfer and Membrane Blocking

Following electrophoresis, separated proteins are transferred from the gel onto a solid membrane support for antibody probing [10].

Transfer Methods:

- Wet Transfer: Uses tank system with large buffer volume, typically performed at low voltage overnight. Provides high efficiency across a wide range of protein sizes and is particularly effective for large proteins (>100 kDa) [10].

- Semi-Dry Transfer: Uses pre-soaked filter sandwiches with transfer time under one hour. More time-efficient but may have reduced efficiency, especially for large proteins [10].

- Transfer Buffer: Towbin buffer (25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 20% methanol, pH 8.3) is standard. Methanol facilitates protein binding to membranes but can reduce transfer efficiency for large proteins; SDS can be added to improve large protein transfer [10].

Membrane Selection:

- Nitrocellulose: Traditional choice with good protein binding capacity. Fragile and less durable for reprobing [10].

- PVDF (Polyvinylidene Difluoride): Superior protein binding capacity, chemical resistance, and mechanical strength. Allows membrane stripping and reprobing. Requires pre-wetting in methanol before use [10].

Blocking:

- Incubate membrane with blocking agents such as 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) or non-fat dry milk in TBST to prevent non-specific antibody binding [31] [32].

- Blocking time typically ranges from 1 hour at room temperature to overnight at 4°C, depending on target abundance and antibody specificity [31].

Stage 4: Immunodetection and Signal Development

Antibody probing enables specific detection of the target protein through antigen-antibody interactions [31] [32].

Primary Antibody Incubation:

- Dilute primary antibody in blocking buffer or specialized antibody diluents according to manufacturer recommendations [31].

- Incubate membrane with primary antibody for 1–2 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C for enhanced sensitivity [31].

- Wash membrane thoroughly with TBST (3 × 5–10 minutes) to remove unbound primary antibody [31].

Secondary Antibody Selection:

- Choose enzyme-conjugated (HRP or AP) or fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies directed against the host species of the primary antibody [32].

- Indirect detection using conjugated secondary antibodies provides signal amplification, as multiple secondary antibodies can bind to each primary antibody [32].

- For western blotting after immunoprecipitation, use light chain-specific secondary antibodies to avoid interference from IP antibody heavy chains when detecting proteins around 50 kDa [32].

- Incubate with appropriately diluted secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature, followed by thorough washing with TBST [31].

Detection Methods:

- Chemiluminescent: HRP-conjugated antibodies catalyze oxidation of luminol substrates, producing light detectable by X-ray film or digital imaging systems. Offers high sensitivity and dynamic range [31].

- Fluorescent: Fluorophore-conjugated antibodies enable direct detection without substrates. Allows multiplexing of multiple targets and provides stable signals for quantitative analysis [28] [33].

- Colorimetric: Enzyme substrates produce insoluble colored precipitates at the target location. Less sensitive but provides permanent visual record [6].

Comparative Analysis: Western Blot vs. Immunohistochemistry

When designing protein detection experiments, understanding the complementary strengths and limitations of western blot and IHC is essential for appropriate technique selection [6] [28].

Table 2: Western Blot vs. Immunohistochemistry Comparison

| Parameter | Western Blot | Immunohistochemistry (IHC) |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Type | Cell or tissue lysates [28] | Intact tissue sections [28] |

| Protein State | Denatured, linearized epitopes [31] | Native conformation in cellular context [2] |

| Key Strengths | Molecular weight determination, semi-quantification, post-translational modification detection [33] | Cellular and subcellular localization, tissue architecture preservation [28] |

| Limitations | No spatial information, requires protein extraction [6] | Semi-quantitative at best, no molecular weight information [6] |

| Throughput | Medium, limited multiplexing capability [33] | Low to medium, but enables multiplexing [2] |

| Data Output | Band intensity proportional to protein amount [6] | Cellular staining patterns indicating protein distribution [2] |

| Antibody Concerns | Recognizes denatured linear epitopes [19] | Requires antibodies recognizing native conformation [19] |

Technique Selection Criteria:

- Choose Western Blot when research questions involve protein molecular weight confirmation, semi-quantitative comparison of protein abundance between samples, detection of post-translational modifications, or analysis of protein expression in homogeneous cell populations [33].

- Choose IHC when research questions involve determining protein localization within tissue architecture, analyzing protein expression in heterogeneous cell populations, or examining subcellular distribution patterns [28] [2].

Essential Reagents and Research Solutions

Successful western blotting requires optimized reagents and materials at each workflow stage [10] [31] [32].

Table 3: Essential Western Blot Reagents and Their Functions

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Lysis Buffers | RIPA buffer, Non-denaturing lysis buffers | Extract proteins from cells or tissues while maintaining integrity of target epitopes [31] |

| Protease Inhibitors | PMSF, Complete protease inhibitor cocktails | Prevent protein degradation during extraction by inhibiting endogenous proteases [31] |

| Electrophoresis | SDS-PAGE gels, Tris-Glycine/MOPS/MES running buffers | Separate denatured proteins based on molecular weight [10] [31] |

| Transfer Systems | Nitrocellulose membranes, PVDF membranes, Towbin transfer buffer | Immobilize separated proteins for antibody probing [10] |

| Blocking Agents | BSA, non-fat dry milk | Prevent non-specific antibody binding to membrane [31] [32] |

| Detection Antibodies | HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies, fluorescent secondaries | Enable specific target detection with signal amplification [32] |

| Detection Substrates | ECL, SuperSignal West Dura, fluorescent scanners | Generate measurable signal corresponding to target protein abundance [31] [33] |

Troubleshooting and Quality Considerations

Common Challenges and Solutions:

- High Background: Increase blocking time, optimize antibody concentrations, extend wash times, or change blocking agents [31] [32].

- Weak or No Signal: Check antibody specificity using positive controls, increase protein loading, enhance detection sensitivity with signal amplification, or verify antigen accessibility [19] [30].

- Non-Specific Bands: Include isotype controls, use monoclonal instead of polyclonal antibodies, or try different antibody clones [30].

- Poor Transfer Efficiency: Verify membrane compatibility with transfer method, adjust methanol concentration in transfer buffer, or extend transfer time for high molecular weight proteins [10].

Antibody Validation Concerns: Recent comprehensive studies highlight that antibody performance is highly context-dependent, with significant variability between applications [19] [29] [30]. Systematic validation of 79 Tau antibodies revealed that over half exhibited non-selective binding to other proteins in western blot applications, emphasizing the necessity of application-specific antibody validation [30]. When selecting antibodies, prioritize those specifically validated for western blotting rather than assuming cross-application functionality [19] [29].

Quantitative Considerations: While western blot provides semi-quantitative data, several factors affect quantitative accuracy:

- Ensure linear range of detection by testing multiple exposure times and protein loads [33].

- Include loading controls (e.g., housekeeping proteins) to normalize for variations in total protein loading [10].

- Use appropriate image analysis software for densitometric measurement of band intensity [10].

- For precise quantification, consider complementary techniques such as ELISA which may offer better quantitative accuracy for absolute protein concentration determination [33].

The western blot workflow, from cell lysis to semi-quantitative band detection, provides researchers with a powerful tool for protein analysis that complements rather than replaces techniques like IHC. While western blot excels at determining molecular weight and providing semi-quantitative data on protein abundance, IHC offers superior spatial context within tissues and cells [6] [28]. The technique's enduring value lies in its ability to specifically detect target proteins in complex mixtures, provide information on protein size and modification state, and generate reproducible, semi-quantifiable data [33].

Understanding the application-specific limitations of antibodies is crucial for experimental design and data interpretation [19] [30]. As research continues to advance, western blotting maintains its position as an essential technique in the molecular biology toolkit, particularly when applied alongside complementary methods like IHC to provide a more comprehensive understanding of protein expression and function.

In the fields of cancer research and diagnostics, the ability to accurately detect and localize specific proteins is paramount. Two of the most pivotal techniques for protein analysis are Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and Western blot. While both leverage the specific binding of antibodies to target antigens, they provide fundamentally different types of information [6]. IHC excels at visualizing the spatial distribution of proteins within the context of intact tissue architecture, making it indispensable for diagnostics and biomarker mapping [1] [34]. In contrast, Western blot is a quantitative technique that separates proteins by molecular weight, providing information on protein presence and relative amount in a lysate [10]. This guide offers a detailed, objective comparison of these two techniques, focusing on their application in cancer research and the critical role of IHC in advancing personalized medicine.

Technical Comparison: IHC vs. Western Blot

The core difference between these techniques lies in their output: IHC provides contextual, spatial data, while Western blot provides quantitative, size-based data.

The table below summarizes their key characteristics:

| Feature | Immunohistochemistry (IHC) | Western Blot |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Type | Tissue sections (frozen or paraffin-embedded) [6] [34] | Cell or tissue extracts (lysates) [6] [34] |

| Protein State | In situ, fixed [2] | Denatured [10] |

| Key Output | Localization and distribution of protein within tissue structure [1] | Presence and relative quantity of protein based on molecular weight [6] |

| Spatial Context | Preserved; allows visualization in morphological context [1] [34] | Lost during sample homogenization [6] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Easily multiplexed to detect multiple targets simultaneously (e.g., 4+ colors) [2] | Limited multiplexing; possible with fluorescent tags but challenging [2] |

| Quantification | Semi-quantitative (based on staining intensity and distribution) [1] | Quantitative (densitometric analysis of bands) [10] |

| Primary Applications | Diagnostics, biomarker discovery and mapping, subcellular localization, tumor classification [1] [35] | Confirmatory protein detection, measuring expression levels, studying protein modifications [36] [34] |

A key advantage of IHC is its ability to determine the subcellular compartmentalization of proteins and analyze expression in mixed cell populations directly from tissue, which is highly limited in Western blot [2]. Conversely, Western blot's most prominent advantage is its ability to generate a signal proportional to the amount of target protein and confirm its molecular weight [6].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflows for each technique, highlighting their distinct processes from sample to result:

IHC in Action: Cancer Biomarker Mapping

IHC is a cornerstone technique in modern pathology, playing a critical diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive role in oncology [1].

Key Clinical Applications of IHC

- Diagnosis and Tumor Classification: IHC is used to identify the cell type and origin of a cancer, which is crucial for determining the appropriate treatment strategy. For example, it is used to distinguish between different subtypes of carcinoma, lymphoma, and sarcoma [1].

- Prognostic Biomarkers: The technique helps identify biomarkers that provide information about the likely course of the disease, such as the proliferation marker Ki-67, which indicates how quickly tumor cells are dividing [1] [2].

- Predictive Biomarkers: IHC is vital for detecting proteins that predict response to specific targeted therapies. The most established examples are the detection of hormone receptors (ER/PR) and the HER2 protein in breast cancer, which directly determine eligibility for hormone therapy or HER2-targeted drugs like trastuzumab [1] [37].

- Infectious Disease Identification: IHC can pinpoint the presence of infectious agents within tissues, such as viruses associated with cancer (e.g., HPV in cervical cancer) [1].

Experimental Data: p53 Detection as a Case Study

The performance of IHC as a detection method can be evaluated by comparing its results with genetic sequencing. A study on urothelial bladder carcinoma provides quantitative data on the sensitivity and specificity of IHC for detecting p53 protein overexpression, using polymerase chain reaction-single strand conformational polymorphism (PCR-SSCP) as the genetic "gold standard" [38].

- Overall Performance: The study found IHC had a sensitivity of 65.8% and a specificity of 62.9% when using a 20% cutoff for immunopositivity [38].