Immunochemistry Principles and Techniques: From Basic Concepts to Advanced Applications in Biomedical Research

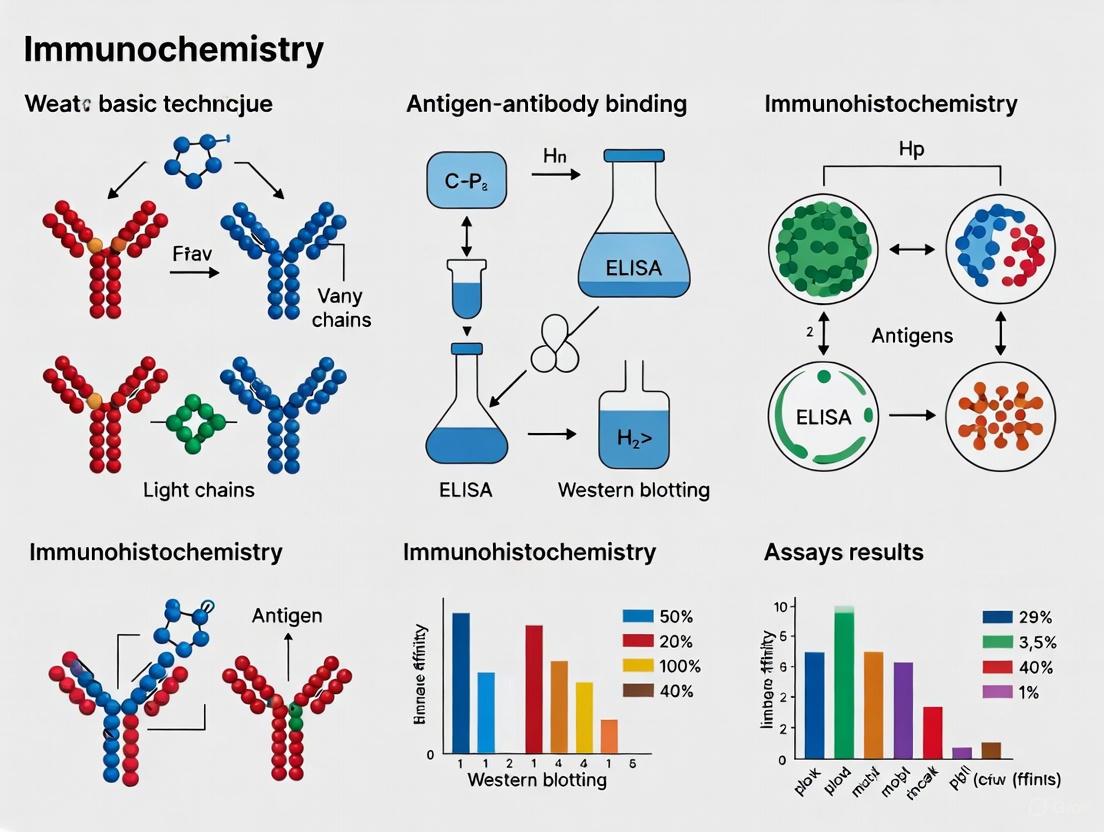

This article provides a comprehensive overview of immunochemistry, a cornerstone technique that combines anatomical, immunological, and biochemical principles to detect specific antigens within cells and tissues.

Immunochemistry Principles and Techniques: From Basic Concepts to Advanced Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of immunochemistry, a cornerstone technique that combines anatomical, immunological, and biochemical principles to detect specific antigens within cells and tissues. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational concepts of antibody-antigen interactions, detailed methodological protocols for applications in disease diagnosis and drug development, practical troubleshooting for common issues, and rigorous standards for assay validation. By synthesizing current methodologies with emerging trends like artificial intelligence and multiplexed analysis, this guide serves as an essential resource for leveraging immunochemistry in both research and clinical settings.

Core Principles and Evolutionary Journey of Immunochemistry

Immunochemistry represents the interdisciplinary fusion of immunology, anatomy, and biochemistry, employing antibody-based techniques to detect and localize specific antigens within their anatomical context. This technical guide explores the core principles, methodologies, and applications of immunohistochemistry (IHC) as a quintessential immunochemical technique. We examine the complete workflow from tissue fixation to quantitative analysis, highlighting the critical convergence of disciplinary knowledge required for successful experimental outcomes. Recent advances in digital image analysis and automated quantification demonstrate the evolving sophistication of the field, offering enhanced reproducibility over traditional pathologist visual scoring. This whitepaper provides detailed protocols and resource guidance to support researchers in implementing robust immunochemical analyses for basic research and drug development applications.

Immunochemistry operates at the unique intersection of three fundamental biological disciplines. From immunology, it derives the exquisite specificity of antibody-antigen interactions. From anatomy, it incorporates the critical importance of structural and spatial context within tissues and cells. From biochemistry, it applies principles of molecular interactions, enzyme kinetics, and chemical staining reactions. This convergence enables the precise localization and quantification of specific molecules within their native morphological environment, providing insights that cannot be gleaned from techniques that homogenize tissues.

The foundational technique of immunohistochemistry (IHC) exemplifies this interdisciplinary approach. IHC exploits the specific recognition of an epitope by an antibody to visualize protein expression in situ while preserving the anatomical and structural features of a tissue sample [1]. First developed in the 1940s by Albert Coons, who created a fluorescein-labeled anti-pneumococcal antibody, the technique has evolved through numerous technical optimizations including enzyme-conjugated antibodies, antigen retrieval methods, and now digital quantification [2]. IHC's exceptional utility lies in its ability to bridge discovery research with clinical application, particularly in biomarker validation and cancer diagnostics [3] [4].

Core Principles and Methodological Framework

Antibody-Antigen Interactions: The Immunological Foundation

The specificity of immunochemical techniques stems from fundamental antibody-antigen interactions. Antibodies are immunoglobulins capable of binding specifically to a wide array of natural and synthetic antigens, including proteins, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids [5]. The strength of this interaction is defined by two key properties: affinity, referring to the thermodynamic energy of interaction between a single antibody-combining site and its corresponding epitope, and avidity, describing the overall binding strength including all combining sites on an antibody molecule [5].

Two principal types of antibodies are used in immunochemistry:

- Polyclonal antibodies: Heterogeneous mixtures derived from different B-cell clones, recognizing multiple epitopes on a target antigen.

- Monoclonal antibodies: Products of a single clone or plasma cell line, recognizing a single epitope with uniform specificity [5].

The antigen-to-antibody ratio significantly impacts complex formation, with optimal precipitation occurring at the equivalence zone where neither free antibody nor free antigen remains in solution [5].

Anatomical Preservation: Tissue Integrity and Architecture

Preservation of tissue architecture is paramount in immunochemistry, distinguishing it from solution-based immunoassays. Proper tissue fixation maintains anatomical relationships while preventing degradation. The choice of fixative represents a critical balance: under-fixed tissues may undergo proteolytic degradation, while over-fixed tissues can experience epitope masking through excessive cross-linking [2].

Common fixation approaches include:

- Formaldehyde-based fixatives: Create methylene cross-links between proteins, offering strong tissue penetration with relatively low background [2].

- Precipitative fixatives (e.g., methanol, ethanol): Cause protein precipitation by altering dielectric points but preserve cell morphology less effectively than cross-linking fixatives [2].

- Perfusion vs. immersion: Perfusion fixation through the vascular system allows rapid fixation of organs, while immersion fixation is suitable for smaller tissue specimens [2].

Following fixation, tissues are typically embedded in paraffin (FFPE) or optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound for sectioning, preserving anatomical relationships for microscopic examination.

Biochemical Detection Systems: Signal Generation and Amplification

Detection methodologies in immunochemistry employ biochemical principles to generate measurable signals from antibody binding events. Two primary detection modalities are employed:

- Chromogenic detection: Utilizes enzyme-conjugated antibodies (e.g., horseradish peroxidase, alkaline phosphatase) that generate colored precipitates at the antigen site [6].

- Fluorescent detection: Employs fluorophore-conjugated antibodies directly visualized through fluorescence microscopy, enabling multiplexed detection of multiple targets [2].

Three principal method architectures govern antibody application:

- Direct method: Primary antibodies are directly labeled with fluorescent dyes or enzymes, shortening experimental time but potentially reducing signal [6].

- Indirect method: Unlabeled primary antibodies are detected using labeled secondary antibodies, providing signal amplification through multiple secondary antibodies binding to each primary [6].

- Amplification method: Incorporates additional amplification steps such as biotin-avidin complexes to enhance signal detection for low-abundance targets [6].

Experimental Workflow: From Tissue to Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for immunohistochemical analysis of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues, integrating critical steps from multiple disciplines:

Sample Preparation and Fixation Protocols

Proper sample preparation preserves anatomical context while maintaining biochemical antigenicity. For FFPE tissues, the following protocol is recommended [6] [1]:

- Fixation: Immerse tissue in 10% neutral buffered formalin (approximately 4% formaldehyde) for 2-24 hours at room temperature, depending on tissue size.

- Embedding: Process fixed tissues through graded ethanol series (70%-100%), clear in xylene, and infiltrate with molten paraffin at 56-58°C.

- Sectioning: Cut paraffin blocks into 4-5 μm sections using a microtome, float in a water bath, and mount on coated glass slides.

- Baking: Dry slides at 60°C for several hours to several days to enhance tissue adhesion.

Alternative approaches include frozen section preparation, where tissues are embedded in OCT compound and sectioned using a cryostat, preserving antigenicity but potentially compromising morphological detail.

Antigen Retrieval and Epitope unmasking

A critical advancement in immunochemistry, antigen retrieval techniques reverse formaldehyde-induced cross-links that mask epitopes. Two primary approaches are employed [6] [1]:

- Heat-Induced Epitope Retrieval (HIER): Incubate slides in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) or Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 9.0) using a microwave oven, water bath, pressure cooker, or autoclave. For microwave retrieval, heat for 10 minutes twice with a 5-minute cooling interval.

- Proteolytic-Induced Epitope Retrieval (PIER): Treat sections with proteinase K (5-20 μg/mL) or pepsin (0.1-0.5%) for 5-20 minutes at room temperature.

Optimization of antigen retrieval method, pH, temperature, and duration is essential for each antibody-epitope combination, as demonstrated by the variable performance of different retrieval methods with specific antibodies [1].

Immunostaining and Detection

The core immunodetection process requires precise optimization of conditions to maximize specific signal while minimizing background [1]:

- Blocking: Incubate sections with 0.5% BSA and 5% serum from the secondary antibody host species for 30 minutes at room temperature to reduce non-specific binding.

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Apply primary antibody diluted in blocking buffer for 1-2 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. Optimal concentration must be determined empirically for each antibody.

- Secondary Antibody Incubation: Incubate with enzyme-conjugated or fluorophore-labeled secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Signal Development:

- For chromogenic detection: Incubate with DAB substrate for 3-10 minutes, monitoring development microscopically.

- For fluorescent detection: Protect from light and proceed to mounting.

Counterstaining, Mounting, and Visualization

Final processing steps contextualize specific staining within tissue morphology [6]:

- Counterstaining: Apply Mayer's hematoxylin for 5 minutes for nuclear staining, followed by bluing in running water for 20 minutes.

- Dehydration and Clearing: Process through graded ethanol series (80%-100%) and xylene.

- Mounting: Apply coverslip using xylene-based hydrophobic mounting medium for long-term preservation.

- Visualization: Image using brightfield microscopy (chromogenic) or fluorescence microscopy with appropriate filter sets.

Quantitative Analysis in Immunochemistry

Traditional pathologist visual scoring of IHC staining has limitations in subjectivity, cost, and generation of ordinal rather than continuous data [3] [4]. Digital image analysis approaches overcome these limitations through automated quantification.

Digital Image Analysis Versus Visual Scoring

A comparative study of 215 ovarian serous carcinoma specimens stained for S100A1 demonstrated strong correlation between digital analysis and pathologist scoring [3] [4]. The table below summarizes key quantitative comparisons:

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of IHC Staining Assessment Methods

| Assessment Metric | Correlation Type | Correlation Coefficient | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of Carcinoma with S100A1 Staining (%Pos) | Spearman | 0.88 | p < 0.0001 |

| Staining Intensity × Percentage Positive (OD*%Pos) | Spearman | 0.90 | p < 0.0001 |

The study utilized Genie Histology Pattern Recognition software for tissue classification and Color Deconvolution algorithms for stain separation, demonstrating that computer-aided methods can produce data highly similar to pathologist evaluation [4].

Automated Quantitative Analysis Algorithms

Recent advances employ deep learning techniques for precise cellular and subcellular quantification. A fully automated method combining CellViT nuclear segmentation with region-growing algorithms accurately quantifies nuclear, membrane, and cytoplasmic expression patterns in whole-slide images [7]. Optical density separation techniques differentiate hematoxylin and DAB staining components, enabling precise quantification of biomarker expression.

Essential Reagents and Research Solutions

Successful immunochemistry requires optimization of multiple reagent systems. The following table outlines key solutions and their functions in the experimental workflow:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Immunochemistry

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Optimization Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixatives | 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin, 4% Paraformaldehyde | Preserve tissue architecture and antigenicity | Duration and temperature critical; overfixation masks epitopes |

| Antigen Retrieval Buffers | Citrate Buffer (pH 6.0), Tris-EDTA Buffer (pH 9.0) | Reverse formaldehyde cross-links | pH optimal for specific epitopes; heating method affects efficiency |

| Blocking Agents | BSA, Serum, Non-fat Dry Milk | Reduce non-specific antibody binding | Match serum species to secondary antibody host |

| Detection Systems | HRP-DAB, Alkaline Phosphatase-Fast Red | Generate visible signal from antibody binding | Enzyme inactivation essential for endogenous activity |

| Counterstains | Hematoxylin, Methyl Green | Provide anatomical context | Differentiation and bluing steps affect nuclear detail |

| Mounting Media | Xylene-based, Aqueous | Preserve staining and optimize microscopy | Match refractive index to microscopy method |

Applications in Research and Drug Development

Immunochemistry serves critical functions across biomedical research and therapeutic development:

- Biomarker Validation: IHC validates genomic discoveries through direct protein visualization in histologically relevant tissue regions, overcoming limitations of homogenization-based assays [4].

- Clinical Diagnostics: IHC identifies pathogenic features including neoplasia, metastasis, infection, and inflammation, with applications in companion diagnostic development [1].

- Therapeutic Target Verification: Spatial localization of drug targets within tissue microenvironments informs target engagement strategies and candidate selection.

- Tumor Microenvironment Analysis: Multiplexed IHC characterizes immune cell infiltration, stromal interactions, and cellular heterogeneity within tumors, guiding immunotherapy development [8].

Immunochemistry represents the essential convergence of immunology's specificity, anatomy's structural context, and biochemistry's detection principles. This interdisciplinary integration enables the precise spatial localization of biomolecules within their native tissue environments, providing insights inaccessible to reductionist approaches. As the field advances with automated quantification, multiplexed detection, and computational integration, immunochemical techniques will continue to expand their vital role in basic research, translational science, and therapeutic development. The continued refinement of standardized protocols and analytical frameworks will enhance reproducibility and quantitative rigor across applications.

Immunochemistry represents a cornerstone of modern biological science and therapeutic development, fundamentally reliant on the specific interaction between antibodies and antigens. This specific binding event serves as the foundational principle for a vast array of techniques essential for disease diagnosis, biomedical research, and drug development. Antibodies, also known as immunoglobulins, are large Y-shaped glycoproteins produced by B-cells as a primary immune defense, capable of specifically recognizing and binding unique molecular patterns on pathogens called antigens [9]. The exquisite specificity of this interaction enables researchers to detect single proteins within complex biological mixtures, localize biomarkers within tissues with microscopic precision, and quantify minute concentrations of analytes critical for assessing disease states.

The significance of antibody-antigen interactions extends far beyond basic research into clinical applications. Immunoassays form the basis for diagnosing infectious diseases, autoimmune disorders, and cancers, while also monitoring therapeutic drug levels and immune responses. In drug development, these principles are harnessed for target validation, pharmacokinetic studies, and the development of biologic therapies themselves, particularly monoclonal antibodies. The kinetics and affinity of these interactions directly influence assay sensitivity and therapeutic efficacy, making their thorough understanding paramount for professionals in these fields [10]. As biological therapies and precision medicine continue to advance, the principles governing antibody-antigen reactions remain fundamentally important for innovating new detection technologies and therapeutic strategies.

Structural and Biochemical Principles

Antibody Structure and Function

The characteristic Y-shaped antibody molecule consists of four polypeptide chains: two identical heavy chains and two identical light chains, stabilized by disulfide bonds [9]. These chains organize into distinct structural and functional domains:

- Variable regions (V) located at the amino-terminal ends of both heavy and light chains form the antigen-binding site (paratope). This region contains three hypervariable complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) that create the unique molecular surface complementary to the antigen's epitope.

- Constant regions (C) form the Fragment crystallizable (Fc) region and determine the antibody's isotype, which dictates its functional properties and interactions with other immune system components [9].

The antibody structure can be divided functionally into F(ab) and Fc regions. Proteolytic cleavage with enzymes like papain separates these domains: the F(ab) region contains the antigen-binding sites, while the Fc region mediates effector functions such as complement activation and binding to Fc receptors on immune cells [9]. This structural duality enables antibodies to simultaneously recognize specific antigens while recruiting immune responses, a feature exploited in many immunoassay designs.

Antigen Characteristics and Epitope Recognition

Antigens are substances that can elicit an immune response and be specifically recognized by antibodies or T-cell receptors. Effective antigens typically possess several key characteristics:

- Molecular complexity with areas of structural stability

- Minimal molecular weight of 8,000-10,000 Da, though haptens (small molecules) can become immunogenic when conjugated to carrier proteins

- Immunogenic amino acids such as lysine, arginine, glutamic acid, aspartic acid, glutamine, and asparagine in significant proportions [9]

The specific portion of the antigen recognized by an antibody is called an epitope. Epitopes can be classified as:

- Linear epitopes: consisting of a contiguous sequence of amino acids

- Conformational epitopes: formed by spatially adjacent amino acids from different regions of the antigen brought together by protein folding

The antibody-antigen interaction occurs between the paratope of the antibody and the epitope of the antigen, maintained by non-covalent forces including van der Waals interactions, hydrogen bonds, electrostatic attractions, and hydrophobic effects [9]. The strength of this interaction is defined by affinity (the binding strength between a single paratope-epitope pair) and avidity (the overall binding strength when multiple interactions occur simultaneously, as with multivalent antibodies like IgM).

Table 1: Antibody Isotypes and Their Functions

| Isotype | Heavy Chain | Structure | Molecular Weight (kDa) | Primary Functions and Locations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgA | α | Monomer - tetramer | 150-600 | Mucosal immunity; found in gut, respiratory, urogenital tracts; secreted in milk |

| IgD | δ | Monomer | 150 | B cell receptor; function not fully defined |

| IgE | ε | Monomer | 190 | Allergy response; protection against parasitic worms |

| IgG | γ | Monomer | 150 | Most abundant in serum; provides majority of antibody-based immunity |

| IgM | μ | Pentamer | 900 | First response antibody; high avidity; B cell receptor |

Antigen Processing and Presentation

For T-cell dependent immune responses, the antibody-antigen reaction is preceded by critical processing and presentation steps. The immune system employs two major pathways for presenting antigenic peptides to T-cells:

- MHC Class I Pathway: Processes endogenous antigens (intracellular proteins from viruses or self-proteins). Proteins are degraded by the proteasome, transported into the endoplasmic reticulum by TAP transporters, and loaded onto MHC-I molecules for presentation to CD8+ T-cells [11].

- MHC Class II Pathway: Processes exogenous antigens (extracellular proteins). Antigens are internalized by antigen-presenting cells, degraded in increasingly acidic endosomal compartments, and loaded onto MHC-II molecules with the assistance of the invariant chain for presentation to CD4+ T-cells [12] [11].

These pathways ensure that protein antigens are appropriately processed into peptide fragments and presented in the context of MHC molecules to initiate and shape adaptive immune responses, ultimately leading to antibody production by B-cells.

Diagram 1: Antigen Processing and Presentation Pathways. The MHC Class I pathway processes intracellular antigens for CD8+ T-cell recognition, while the MHC Class II pathway processes extracellular antigens for CD4+ T-cell recognition.

Key Experimental Techniques and Methodologies

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

The Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) is a plate-based technique designed for detecting and quantifying soluble substances such as peptides, proteins, antibodies, and hormones [13]. In an ELISA, the antigen is immobilized on a solid surface (typically a polystyrene microplate) and complexed with an antibody linked to a reporter enzyme. Detection is accomplished by measuring the enzyme's activity via incubation with an appropriate substrate to produce a measurable product. The key steps in a standard ELISA protocol include:

- Coating: Direct or indirect immobilization of antigens to microplate wells

- Blocking: Addition of irrelevant protein to cover all unsaturated binding sites

- Probing: Incubation with antigen-specific antibodies

- Detection: Measurement of signal generated via enzyme-substrate reaction [13]

ELISA formats vary based on experimental needs:

- Direct ELISA: Uses a labeled primary antibody for detection; faster but less sensitive

- Indirect ELISA: Uses an unlabeled primary antibody followed by a labeled secondary antibody; offers signal amplification

- Sandwich ELISA: Employs two antibodies recognizing different epitopes on the target antigen; offers high specificity and sensitivity

- Competitive ELISA: Measures antigen concentration by detecting signal interference from competing labeled and unlabeled antigens; ideal for small antigens with single epitopes [13]

Table 2: Comparison of ELISA Formats

| Format | Sensitivity | Specificity | Steps | Time | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | Moderate | High | Fewest | Shortest | High-abundance targets; quick screens |

| Indirect | High | Moderate | More | Longer | General purpose; enhanced sensitivity |

| Sandwich | Highest | Highest | Most | Longest | Complex samples; low-abundance targets |

| Competitive | High | High | Moderate | Moderate | Small molecules; haptens |

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) combines histological, immunological, and biochemical techniques to detect specific antigens in tissue sections, preserving spatial and morphological context [14] [15]. This technique is indispensable in pathology for disease diagnosis, classification, and prognostic assessment, particularly in oncology. The standard IHC protocol involves:

- Tissue Collection and Fixation: Tissues are typically fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin to preserve cellular morphology and antigenicity.

- Tissue Processing: Embedding in paraffin wax and sectioning into thin slices (4-6 μm) using a microtome.

- Deparaffinization and Rehydration: Removal of paraffin with xylene followed by rehydration through graded alcohol solutions.

- Antigen Retrieval: Application of heat-induced epitope retrieval (HIER) or enzymatic digestion to unmask antigenic sites obscured by formalin fixation.

- Blocking: Incubation with serum or BSA to prevent non-specific antibody binding.

- Antibody Incubation: Sequential incubation with primary antibody and enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody.

- Detection: Application of chromogenic substrate (e.g., DAB for horseradish peroxidase) to produce a colored precipitate at the antigen site.

- Counterstaining and Mounting: Application of hematoxylin to visualize cell nuclei followed by coverslipping for microscopic examination [14] [15].

Recent advances in IHC include multiplex immunohistochemistry, which allows simultaneous detection of multiple targets using different fluorophores, and the integration of digital pathology with AI-based image analysis to improve accuracy and consistency of interpretation [14].

Diagram 2: IHC Experimental Workflow. Key steps in immunohistochemistry from tissue preparation through analysis, highlighting critical antigen retrieval and detection phases.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) for Kinetic Analysis

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) has emerged as a powerful label-free technique for real-time analysis of biomolecular interactions, particularly valuable for determining the kinetic parameters of antibody-antigen interactions [10]. Unlike endpoint assays like ELISA, SPR provides detailed information about association (k~on~) and dissociation (k~off~) rates, from which the equilibrium dissociation constant (K~D~) can be calculated. Recent advances have dramatically improved SPR throughput; for instance, the LSA instrument from Carterra Inc. can simultaneously measure 384 interactions, enabling high-throughput screening of antibody libraries [10].

A notable application of SPR in antibody engineering involves deep mutational scanning of complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) to optimize affinity and specificity. In one study, researchers performed alanine and tyrosine scanning mutagenesis of all CDR residues in an anti-human PD-1 antibody, followed by high-throughput SPR analysis against human and mouse PD-1 [10]. This approach identified specific mutations that enhanced affinity for mouse PD-1 by over 100-fold, demonstrating the power of data-driven antibody design.

Quantitative Analysis of Antibody Kinetics

Understanding the kinetic parameters of antibody-antigen interactions is crucial for both diagnostic and therapeutic applications. Recent longitudinal studies have mapped the kinetics of binding IgA and IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins following booster vaccination, revealing important insights into the duration of protection [16].

Table 3: Antibody Kinetic Parameters and Protection Against Infection

| Parameter | IgG (Wild-Type) | IgG (Omicron BA.1) | IgA (Wild-Type) | IgA (Omicron BA.1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak Response | Day 28 post-booster | Day 28 post-booster | Day 28 post-booster | Day 28 post-booster |

| Waning Rate | Slower for mRNA-1273 | Faster for BNT162b2 | Slower for mRNA-1273 | Faster for BNT162b2 |

| Protection Correlation | High levels at day 28 associated with reduced infection risk (HR: 0.47) | Moderate correlation | Moderate correlation | High levels at day 28 associated with reduced infection risk (HR: 0.36) |

| Duration of Protection | ~155 days to maintain 80% protection at medium incidence | Shorter duration compared to WT | ~155 days to maintain 80% protection at medium incidence | Shorter duration compared to WT |

Key findings from longitudinal antibody studies include:

- Antibody responses wane more rapidly following Pfizer/BioNTech BNT162b2 booster compared to Moderna mRNA-1273 booster [16]

- Higher antibody levels at day 28 post-booster are associated with significantly reduced infection risk

- For BA.1 IgA, a response of at least 20% is needed to sustain 80% protection over 155 days post-booster at medium COVID-19 case incidence [16]

- Mathematical modeling of antibody kinetics can predict durations of protection and inform optimal booster timing

Validation and Quality Control

Antibody Validation Strategies

The reproducibility of research findings using antibody-based techniques depends critically on rigorous antibody validation. The International Working Group for Antibody Validation (IWGAV) has established guidelines to address concerns about antibody specificity and reproducibility [17]. Key validation strategies include:

- Genetic controls: Using knockout cells or tissues to confirm specificity

- Independent-epitope strategies: Employing antibodies targeting different regions of the same antigen

- Orthogonal methods: Verifying results with different methodological approaches

- Bioinformatic validation: Comparing expression patterns with existing databases [17]

For Western blotting, knockout validation is considered the gold standard, while for IHC, proper validation requires demonstration of specific staining patterns in tissues with known expression profiles [17]. Additional considerations include:

- Batch-to-batch variation: A significant source of irreproducibility, particularly with polyclonal antibodies

- Recombinant antibodies: Offer superior consistency compared to traditional hybridoma-derived antibodies

- Application-specific validation: Antibodies must be validated for each specific experimental context [17]

Controls and Standardization

Appropriate controls are essential for ensuring the validity of immunoassay results:

- Positive controls: Validate protocol success using cell lines or tissues known to express the target

- Negative controls: Assess background staining by omitting the primary antibody

- Biological controls: Include tissues with known expression patterns

- Standard reference materials: Enable inter-laboratory comparison and standardization [14]

In IHC, standardization efforts face challenges due to variability in tissue processing, antigen retrieval methods, and detection systems. Recent initiatives promoting automated staining platforms, digital pathology, and algorithm-assisted scoring are improving reproducibility across laboratories [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Antibody-Based Techniques

| Reagent/Category | Function | Examples/Formats | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Antibodies | Bind specifically to target antigen | Monoclonal, polyclonal, recombinant | Specificity validation critical; consider host species for multiplexing |

| Secondary Antibodies | Bind to primary antibodies; conjugated to detection moieties | Enzyme-linked, fluorescent, biotinylated | Must be specific for host species of primary antibody |

| Detection Enzymes | Catalyze signal generation from substrates | Horseradish peroxidase, Alkaline phosphatase | HRP offers higher sensitivity but can be inhibited by azide |

| Chromogenic Substrates | Produce colored precipitate upon enzyme catalysis | DAB (brown), AEC (red), NBT/BCIP (blue-purple) | DAB is most common; produces permanent stain |

| Fluorescent Dyes | Emit light upon excitation at specific wavelengths | FITC, TRITC, Alexa Fluor series | Enable multiplexing; require fluorescence microscope |

| Blocking Reagents | Reduce non-specific binding | BSA, non-fat dry milk, animal sera | Choice affects background; optimize for each application |

| Antigen Retrieval Reagents | Unmask epitopes obscured by fixation | Citrate buffer, EDTA, enzymes | Critical for FFPE tissues; heat-induced methods most common |

| Microplates | Solid phase for assay immobilization | 96-well, 384-well; high binding capacity | Polystyrene with protein binding capacity >400 ng/cm² recommended |

| Sensor Chips | Surface for immobilization in SPR | CM5, NTA, hydrogel-based | Different surfaces optimized for various biomolecules |

The antibody-antigen reaction remains the fundamental principle underlying numerous techniques essential to biomedical research and clinical diagnostics. From the basic structural principles governing this specific interaction to advanced applications in drug development and quantitative kinetic analysis, understanding these interactions enables researchers to design more sensitive, specific, and reproducible experiments. As technology advances, particularly in high-throughput screening, multiplex detection, and computational analysis, the field continues to evolve, offering ever more powerful tools to explore biological systems and develop novel therapeutics. However, these advances must be grounded in rigorous validation and quality control practices to ensure the reliability and reproducibility of the data generated. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering both the fundamental principles and contemporary applications of antibody-antigen interactions remains essential for driving innovation in human health and disease treatment.

The evolution of immunostaining techniques represents a cornerstone of modern biomedical science, enabling researchers and clinicians to visualize specific molecular components within cells and tissues with exceptional precision. From its origins in the early 1940s, immunofluorescence (IF) has expanded into a sophisticated family of methodologies that bridge immunology, histology, and biochemistry [18] [19]. These techniques have become indispensable tools for both fundamental research and clinical diagnostics, particularly in the classification of neoplasms, diagnosis of immunobullous disorders, and understanding of complex cellular environments [18] [20]. This review traces the technical evolution from basic immunofluorescence to contemporary multiplexed imaging and artificial intelligence-driven approaches, framing these developments within the broader context of immunochemistry principles and their applications in research and therapeutic development.

Historical Development of Immunofluorescence

The conceptual foundation for immunofluorescence was established in 1941 by Albert Hewett Coons and his colleagues, who first constructed a fluorescein-isocyanate compound to visualize pneumococcal antigens in infected tissue [18] [21] [19]. This pioneering work demonstrated that antibodies could be tagged with fluorescent markers and used as specific histological stains, creating a new paradigm for antigen localization [19].

For approximately two decades, the field progressed gradually until a significant advance came in 1964, when Beutner and Jordon utilized indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) to detect antibodies in sera from patients with pemphigus vulgaris [18] [21]. This innovation amplified detection signals and expanded the technique's diagnostic utility. Around the same period, in 1963, researchers first described granular deposits of IgG and C3 along the dermo-epidermal junction in lupus erythematosus lesions, establishing immunofluorescence as a crucial diagnostic tool for autoimmune connective tissue diseases [18].

The subsequent development of complement binding indirect immunofluorescence further enhanced sensitivity by exploiting the amplification potential of complement activation. This three-step technique generates numerous C3 molecules at antigen-antibody binding sites, enabling detection even when few IgG or IgM antibodies bind to tissue antigens [18].

Core Immunofluorescence Techniques and Principles

Fundamental Principles

Immunofluorescence techniques share a common principle: exploiting the specific binding between antibodies and antigens to localize target molecules within biological samples, with detection enabled by fluorophore tags [19]. The specific region an antibody recognizes on an antigen is called an epitope, and antibodies differ in their binding affinity for these epitopes [19]. The conjugated fluorophore absorbs light at a specific shorter wavelength and emits it at a longer wavelength, producing detectable fluorescence when examined under appropriate microscopy systems [18] [19].

Direct Immunofluorescence (DIF)

Direct immunofluorescence is a one-step histological staining procedure that identifies in vivo antibodies bound to tissue antigens [18]. In this method, a single fluorophore-conjugated antibody directly binds to the target antigen [19]. The procedure involves obtaining tissue specimens (typically via punch biopsy), snap-freezing them, cutting frozen sections (4-6μm), and overlaying the sections with FITC-conjugated antibodies specific to immunoglobulins (IgG, IgM, IgA), complement components (C3), or fibrin [18].

The key advantage of DIF lies in its procedural simplicity and reduced non-specific background signal, as fewer processing steps minimize potential errors and antibody cross-reactivity [19]. However, its limitation includes potentially reduced sensitivity due to the limited number of fluorophore-labeled antibodies that can bind to each antigen [19].

Indirect Immunofluorescence (IIF)

Indirect immunofluorescence employs two types of antibodies: an unlabeled primary antibody that binds specifically to the target epitope, and a fluorophore-tagged secondary antibody that recognizes and binds to the primary antibody [18] [19]. This technique provides significant signal amplification because multiple secondary antibodies can bind to a single primary antibody, increasing the number of fluorophore molecules per antigen [19]. This enhanced sensitivity makes IIF particularly valuable for detecting low-abundance antigens and for serological studies identifying circulating antibodies in body fluids [18].

The standard IIF protocol involves incubating substrate sections with serial dilutions of the patient's serum, followed by application of FITC-conjugated anti-IgG or other antibody conjugates of defined specificity [18]. Appropriate positive and negative control sera must be tested simultaneously to ensure result validity [18].

Table 1: Comparison of Direct and Indirect Immunofluorescence Techniques

| Parameter | Direct Immunofluorescence (DIF) | Indirect Immunofluorescence (IIF) |

|---|---|---|

| Steps | One-step procedure | Two-step procedure |

| Antibodies Used | Single fluorophore-conjugated antibody | Primary unlabeled antibody + fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody |

| Procedure Time | Shorter | Longer |

| Sensitivity | Lower | Higher due to signal amplification |

| Specificity | High | Potentially reduced due to additional step |

| Background Signal | Lower | Potentially higher |

| Flexibility | Limited | High (different secondary antibodies can be used with same primary) |

| Common Applications | Detecting in vivo antibody deposition in tissue | Detecting circulating antibodies in serum, research applications |

Specialized Immunofluorescence Variations

Several sophisticated IF variations have been developed to address specific diagnostic and research challenges:

Salt Split Technique: This method distinguishes between subepidermal blistering conditions with similar DIF findings by incubating normal human skin in 1M NaCl for 48-72 hours to split it at the lamina lucida level. Bullous pemphigoid antibodies bind to the roof (epidermal side) and floor (dermal side) of the split skin, while epidermolysis bullosa acquisita antibodies bind solely to the dermal side [18].

Antigenic Mapping: Used to differentiate between major forms of epidermolysis bullosa, this method involves creating a mechanically induced blister and performing indirect immunofluorescence with antibodies against different antigenic components of the dermal-epidermal junction (bullous pemphigoid antigen, laminin, type 4 collagen). The cleavage plane is determined by noting which antigens are detected on the roof versus the floor of the induced blisters [18].

Complement Indirect Immunofluorescence: This three-step technique increases detection sensitivity by exploiting complement activation. First, tissue sections are incubated with heat-inactivated serum to destroy complement-fixing activity. Sections are then treated with a complement source (fresh human serum), followed by fluorescein-labeled anti-human C3 antibodies. The method detects C3 molecules generated at antigen-antibody binding sites, providing enhanced sensitivity when minimal specific antibodies are present [18].

The Emergence and Evolution of Immunohistochemistry

While immunofluorescence revolutionized antigen detection, it faced limitations in routine clinical settings due to requirements for fluorescence microscopy and specialized expertise. This prompted the development of immunohistochemistry (IHC), which utilizes enzyme-substrate reactions (e.g., horseradish peroxidase or alkaline phosphatase) rather than fluorophores for signal detection [14] [21]. IHC offers the significant advantage of being viewable with standard light microscopy without specialized equipment [14].

The critical breakthrough for IHC came with the development of antigen retrieval (AR) methods by Shi et al., which reversed the cross-linking effects of formalin fixation and paraffin embedding, making epitopes more accessible to antibody binding [20]. This advancement dramatically expanded IHC applications to archived formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue samples, which are easily stored and widely available in clinical settings [20].

Table 2: Evolution of Key Immunostaining Milestones

| Time Period | Technological Development | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 1941 | First immunofluorescence by Coons et al. | Enabled specific antigen visualization in tissue |

| Early 1960s | Application to autoimmune skin diseases | Established diagnostic utility for immunobullous diseases |

| 1964 | Indirect immunofluorescence by Beutner and Jordon | Signal amplification for enhanced sensitivity |

| 1970s-1980s | Monoclonal antibody development | Increased specificity and reproducibility |

| 1990s | Antigen retrieval techniques | Enabled IHC on archived FFPE tissues |

| 2000s | Automated staining systems | Improved standardization and throughput |

| 2010s | Multiplex immunofluorescence | Simultaneous detection of multiple markers |

| 2020s | AI-powered image analysis and virtual staining | Enhanced quantification and prediction capabilities |

Modern Techniques and Current Status

Multiplex Immunofluorescence (mIF)

A paradigm shift in immunostaining occurred with the development of multiplex immunofluorescence, which enables simultaneous detection of numerous markers within a single tissue section [22] [23]. This capability is particularly valuable for analyzing complex cellular environments, such as the tumor microenvironment, where understanding spatial relationships between different cell types is crucial [22]. Technologies such as Co-Detection by Indexing (CODEX), cyclic immunofluorescence (CyCIF), and multiplexed immunohistochemistry (mIHC) now permit visualization of dozens of proteins simultaneously, providing unprecedented insights into cellular interactions and functional states [22] [23].

However, mIF presents substantial challenges, particularly technical variations in staining intensities arising from differences in tissue fixation, antibody concentrations, and imaging conditions [22]. These variations necessitate robust normalization procedures to ensure accurate biological interpretations across samples and batches.

Normalization and Standardization Approaches

Recent computational advances have addressed normalization challenges in multiplex imaging. The UniFORM pipeline represents a significant innovation—a non-parametric, Python-based method for normalizing multiplex tissue imaging data at both feature and pixel levels [22]. UniFORM employs automated rigid landmark registration tailored to the distributional characteristics of MTI data, aligning biologically invariant negative populations to remove technical variation while preserving tissue-specific expression patterns in positive populations [22]. Benchmarking across multiple platforms (CyCIF, ORION, COMET) demonstrates that UniFORM consistently outperforms existing methods in mitigating batch effects while maintaining biological signal fidelity [22].

Artificial Intelligence and Virtual Staining

The integration of artificial intelligence represents the current frontier in immunostaining technology. ROSIE (RObust in Silico Immunofluorescence from H&E images) is a deep-learning framework that computationally imputes the expression and localization of dozens of proteins from standard H&E images [23]. Trained on a massive dataset of over 1,300 tissue samples co-stained with H&E and CODEX (spanning over 16 million cells), ROSIE can predict 50 different biomarkers from H&E input alone [23]. This approach demonstrates particular utility in identifying immune cell subtypes like B cells and T cells that are not readily discernible with H&E staining alone, offering a powerful tool for enhancing standard histopathological practice without additional costly staining procedures [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Their Functions

| Reagent/Material | Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Antibodies | Bind specifically to target antigens | Monoclonal (higher specificity) or polyclonal (higher sensitivity); require optimization of dilution [20] |

| Secondary Antibodies | Bind to primary antibodies; conjugated with fluorophores or enzymes | Enable signal amplification; must match host species of primary antibody [19] |

| Fluorophores | Emit light at specific wavelengths when excited | FITC, TRITC, Alexa Fluor series; choice depends on microscope filters and experimental design [18] [19] |

| Enzymatic Labels | Catalyze color-producing reactions | Horseradish peroxidase (HRP) or alkaline phosphatase (AP); used with chromogens like DAB [21] [20] |

| Fixatives | Preserve cellular structure and prevent degradation | Paraformaldehyde (PFA), methanol; choice affects epitope preservation [21] [20] |

| Antigen Retrieval Buffers | Reverse cross-linking from fixation | Citrate-based, EDTA, or commercial solutions; critical for FFPE tissues [20] |

| Blocking Reagents | Reduce non-specific antibody binding | BSA, normal serum, or commercial blockers; minimize background staining [21] [20] |

| Mounting Media | Preserve samples for microscopy | May include anti-fading agents for fluorescence; choice affects signal preservation [18] |

Experimental Protocols

Standard Direct Immunofluorescence Protocol

For detecting in vivo antibody deposition in skin diseases [18]:

- Sample Collection: Obtain perilesional skin via 3-5 mm punch biopsy or surgical biopsy.

- Preservation: Snap-freeze specimen immediately in liquid nitrogen or cold solid carbon dioxide. If delay occurs, keep in cold saline. Alternatively, use Michel's medium for transport at ambient temperature.

- Sectioning: Cut frozen 4-6μm sections using a cryostat and place on glass slides. Air-dry for 15 minutes.

- Staining: Rinse in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.2. Overlay slides in a moist chamber with FITC conjugates having specificities for anti-IgG, anti-IgM, anti-IgA, anti-C3, and anti-fibrin (testing each reagent on separate slides).

- Visualization: Rinse in PBS, mount in buffered glycerin, and examine under a fluorescence microscope.

Immunohistochemistry Protocol for FFPE Tissues

For detecting specific antigens in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues [20]:

- Slide Preparation: Section FFPE blocks at 4-7μm thickness, mount on adhesion-treated slides, and dry at 60°C for at least 2 hours (preferably overnight).

- Deparaffinization and Rehydration:

- Immerse slides in 3 changes of xylene (10 minutes each)

- Dip in graded alcohols sequentially (100%, 100%, 80%, to 70%)

- Immerse in deionized water

- Antigen Retrieval:

- Place slides in retrieval buffer (e.g., 10mM citrate)

- Heat using microwave oven (100°C for 5-10 minutes) or pressure cooker

- Cool slides for 15 minutes

- Blocking:

- Inhibit endogenous peroxidase with 3% hydrogen peroxide (5 minutes)

- Apply blocking reagent to decrease nonspecific background staining (e.g., Background Sniper)

- Antibody Incubation:

- Apply optimized concentration of primary antibody for appropriate duration

- Rinse and apply labeled secondary antibody (if using indirect method)

- Detection:

- Apply enzyme substrate (e.g., DAB for peroxidase)

- Counterstain with hematoxylin

- Dehydrate, clear, and mount for light microscopy

Visualization of Technique Evolution and Relationships

The journey from Coons' initial fluorescent antibody conjugates to contemporary multiplexed imaging and AI-powered virtual staining reflects a remarkable technological evolution in immunostaining. Throughout this progression, the fundamental principle has remained constant: exploiting the specific binding between antibodies and antigens to visualize molecular components within biological samples. What has evolved dramatically is the sensitivity, multiplexing capability, quantitative precision, and accessibility of these techniques. Current research focuses not only on developing new fluorophores and detection methods but also on computational approaches that extract unprecedented information from existing staining methods or even predict immunofluorescence patterns from standard H&E stains. As these technologies continue to advance, they will further bridge the gap between morphological observation and molecular characterization, enhancing both fundamental biological understanding and clinical diagnostic capabilities in anatomic pathology, drug development, and personalized medicine.

In the field of immunochemistry, antibodies are indispensable tools for detecting, quantifying, and localizing specific antigens within biological samples. These reagents form the foundation of numerous diagnostic and research applications, from basic science to drug development. Antibodies are broadly classified into two categories based on their origin and specificity: polyclonal antibodies (pAbs), a heterogeneous mixture produced by multiple B-cell clones, and monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), a homogeneous population derived from a single B-cell clone [24] [25]. The strategic selection between these antibody types, along with appropriate labeling strategies, is critical for experimental success, influencing outcomes in techniques such as immunohistochemistry (IHC), immunofluorescence (IF), western blotting, and flow cytometry.

Immunohistochemistry, the most common immunostaining technique, perfectly exemplifies the importance of antibody choice. IHC amalgamates principles from histology, immunology, and biochemistry to precisely localize target antigens within tissue samples, offering a unique advantage over other molecular biology techniques by preserving spatial and morphological context [14]. This technical guide provides an in-depth comparison of monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies, details their production and labeling methodologies, and outlines their applications within modern research and therapeutic contexts, providing scientists with the knowledge to make informed reagent decisions.

Fundamental Differences Between Monoclonal and Polyclonal Antibodies

The core distinction between monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies lies in their specificity and heterogeneity. Polyclonal antibodies are produced by multiple different B cell lineages within an immunized host animal. They recognize a wide array of epitopes—distinct molecular regions—on a single target antigen. This results in a diverse mixture of antibody molecules with varying paratopes and affinities for the antigen [24] [25]. In contrast, monoclonal antibodies originate from a single, immortalized B cell clone. Consequently, every mAb molecule is identical, exhibiting uniform structure and unparalleled specificity for a single, unique epitope on an antigen [24] [25].

This fundamental difference drives their respective strengths and weaknesses, making each type suitable for different experimental scenarios. The following table summarizes the key characteristics and comparative advantages of each antibody type.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Monoclonal vs. Polyclonal Antibodies

| Characteristic | Monoclonal Antibodies (mAbs) | Polyclonal Antibodies (pAbs) |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Single B cell clone [24] [25] | Multiple B cell clones [24] [25] |

| Epitope Specificity | Single, defined epitope [24] [25] | Multiple, different epitopes [24] |

| Specificity & Cross-Reactivity | High specificity; low cross-reactivity [24] | Broader specificity; increased potential for cross-reactivity [24] |

| Homogeneity & Batch Variability | Homogeneous population; minimal lot-to-lot variability [24] | Heterogeneous population; significant batch variability [24] |

| Typical Production Time | ~6 months (complex process) [24] | ~3 months (straightforward process) [24] |

| Development Cost | High [24] [25] | Low to moderate [24] [25] |

| Best Uses | Detecting specific antigens or single protein family members; assays requiring high consistency (e.g., flow cytometry, IF, diagnostics, therapeutics) [24] [25] | Detecting low-abundance targets, denatured proteins, or multiple isoforms; capturing antigen (e.g., immunoprecipitation); western blotting [24] |

Antibody Production Methodologies

Monoclonal Antibody Production via Hybridoma Technology

The production of monoclonal antibodies is a more complex and protracted process, with the classic method being hybridoma technology. The workflow begins with the immunization of a host animal, typically a mouse or rabbit, with the target antigen to elicit an immune response [24]. Once a sufficient immune response is mounted, B-cells are isolated from the animal's spleen. These B-cells are then fused with immortalized myeloma cells (cancerous B-cells) to create hybrid cells known as hybridomas [24]. This fusion step is critical, as it confers the B-cell's ability to produce a specific antibody with the myeloma cell's capacity for indefinite division.

The resulting pool of hybridomas is subsequently diluted and screened in a process called limiting dilution cloning to isolate single cells producing the antibody of desired specificity. Each selected hybridoma clone is then propagated, creating a stable and renewable source of genetically identical monoclonal antibodies [24]. These antibodies are secreted into the culture supernatant, from which they can be harvested and purified. For large-scale production, hybridomas can be injected into the peritoneal cavity of a mouse to produce antibody-rich ascites fluid [24].

Diagram 1: Monoclonal Antibody Production Workflow

Recombinant Monoclonal Antibodies

An advanced and increasingly prevalent method for mAb production bypasses hybridomas altogether, leveraging recombinant DNA technology. This involves cloning the genes encoding the variable regions of the antibody from B-cells and expressing them in controlled host systems, such as mammalian or microbial cells [24] [26]. Recombinant mAbs offer significant advantages, including superior batch-to-batch consistency, defined amino acid sequences, the potential for animal-free production, and the ability to be engineered for enhanced properties like humanization or altered effector functions [24] [27].

Polyclonal Antibody Production

The production of polyclonal antibodies is a more direct process. A host animal—such as a rabbit, goat, or sheep—is immunized with the target antigen following a scheduled protocol over several weeks [24] [25]. This triggers a natural immune response, activating multiple B-cell clones that each produce antibodies against different epitopes of the antigen. After the immunization period, the polyclonal antibodies are harvested by drawing blood and purifying the IgG fraction from the serum [24]. While faster and less expensive than mAb production, this method results in a heterogeneous antibody mixture with inherent batch-to-batch variability, as a new animal must be immunized for each production run [24].

Antibody Labeling Techniques and Kits

For detection in most experimental applications, antibodies must be conjugated to detectable labels, such as enzymes, fluorescent dyes, or other markers. The choice of labeling strategy profoundly impacts the sensitivity, specificity, and signal-to-noise ratio of an assay.

Conventional Labeling Methods

Traditional antibody labeling kits often rely on amine-reactive chemistry. These kits use reactive dyes that covalently bind to free lysine residues (primary amines) on the antibody molecule [28]. While effective, this is a non-site-specific method. Since antibodies contain multiple lysines, this can result in heterogeneous labeling, with dyes potentially attaching to the antigen-binding site (paratope) and impairing antibody affinity [28]. Examples of such kits include the Alexa Fluor Antibody Labeling Kits and Zip Rapid Antibody Labeling Kits, which offer protocols ranging from 15 to 60 minutes [28].

Site-Specific Labeling Methods

To overcome the limitations of conventional chemistry, advanced site-specific labeling methods have been developed. A prominent example is the SiteClick Antibody Labeling Kit [28]. This technology targets the carbohydrate groups located on the Fc region of the antibody heavy chain, well away from the antigen-binding sites. It uses a copper-free click chemistry reaction to attach labels specifically to this site [28]. This approach ensures uniform labeling, preserves antigen-binding affinity, and produces highly consistent conjugates. The trade-off is a longer protocol time, typically 6 to 18 hours, but it yields superior reagents for sensitive applications [28].

Table 2: Comparison of Common Antibody Labeling Kit Types

| Kit Type / Characteristic | Zenon (Affinity) | Zip Rapid (Amine-Reactive) | SiteClick (Site-Specific) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Label Target/Method | Fc portion of IgG / Antibody affinity [28] | Free lysines / Covalent amine-reactive chemistry [28] | Carbohydrates on IgG heavy chain / Click chemistry [28] |

| Protocol Time | ~5 minutes [28] | ~15 minutes [28] | 6-18 hours [28] |

| Site-Specific? | No [28] | No [28] | Yes [28] |

| Conjugate Storage | Not recommended (>24 hr) [28] | Yes [28] | Yes [28] |

| Requires Purification? | No [28] | No [28] | Yes (included) [28] |

| Optimal Applications | Rapid screening, IF, FC [28] | IF, FC, WB, HCA [28] | Highly sensitive IF, FC, HCA requiring minimal background [28] |

Applications in Research and Therapeutics

Research Applications: A Guide to Selection

The choice between monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies is dictated by the specific requirements of the experimental application.

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC): Both antibody types are widely used. Polyclonals are often preferred for detecting low-abundance targets due to their signal amplification from multiple epitope binding. Monoclonals are favored when high specificity is needed to distinguish between closely related protein isoforms, offering lower background staining [24] [14]. Rigorous validation using positive and negative controls is essential for reliable IHC results [14] [29].

- Western Blotting: Polyclonal antibodies are excellent for detecting denatured proteins, as they can bind multiple linear epitopes exposed upon protein denaturation. Monoclonals are ideal for confirming the identity of a specific band or when probing for post-translational modifications like phosphorylation [24].

- Flow Cytometry / Immunofluorescence (IF): Monoclonal antibodies are generally the gold standard. Their singular specificity results in clean staining with low background, which is crucial for accurately quantifying protein expression levels. The use of polyclonals in flow cytometry can lead to incorrect quantification due to signal amplification [24].

- Immunoprecipitation (IP): Polyclonal antibodies are superior for "pulling down" a target protein from a complex solution because their ability to bind multiple epitopes increases the efficiency of antigen capture [24].

Therapeutic and Diagnostic Applications

Monoclonal antibodies have revolutionized medicine, forming the backbone of precision medicine by targeting specific disease mechanisms.

- Oncology: mAbs like trastuzumab (targeting HER2) and pembrolizumab (a PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor) have transformed cancer treatment. Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs), such as trastuzumab emtansine, combine the targeting ability of a mAb with the cell-killing power of a cytotoxic drug, delivering the payload directly to cancer cells [26] [30].

- Bispecific Antibodies: These engineered mAbs can engage two different targets simultaneously. For example, some bispecifics physically bridge T-cells with cancer cells to induce a targeted immune attack, creating novel therapeutic mechanisms [26].

- Autoimmune & Infectious Diseases: mAbs like adalimumab are used to modulate immune responses in rheumatoid arthritis, while others like sipavibart provide passive immunity against pathogens such as SARS-CoV-2 for immunocompromised individuals [30].

- Neurological Disorders: mAbs like aducanumab and lecanemab target amyloid-beta plaques in Alzheimer's disease, representing a promising approach to slowing disease progression [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

Successful immunochemistry experiments rely on a suite of core reagents and solutions beyond just the primary antibody.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Immunochemistry Workflows

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Primary Antibodies (mAb/pAb) | The key reagent that provides specificity by binding the target antigen [24]. |

| Labeled Secondary Antibodies | Enable detection by binding to the primary antibody and carrying a label (enzyme, fluorophore) [14]. |

| Blocking Buffers | Contain irrelevant proteins (e.g., BSA) to adsorb to non-specific sites, minimizing background staining [14] [29]. |

| Antigen Retrieval Solutions | Critical for IHC on FFPE tissues; reverse formaldehyde-induced cross-links to unmask hidden epitopes (e.g., Heat-Induced Epitope Retrieval) [14] [29]. |

| Fixatives | Preserve tissue architecture and prevent antigen degradation (e.g., formalin) [14] [29]. |

| Chromogenic Substrates | Enzymes (HRP, AP) on antibodies convert these substrates into an insoluble, colored precipitate for visualization [14]. |

| Detection Kits (e.g., Polymer-Based) | Multi-component systems that significantly amplify the detection signal, enhancing sensitivity [14] [29]. |

| Mounting Media | Preserve the stained sample under a coverslip for microscopy; may contain antifade agents for fluorescence [14]. |

The field of antibody technology is dynamic, with several key trends shaping its future. There is a marked shift from traditional monospecific mAbs toward more complex bispecific antibodies and antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), which now constitute a significant portion of new approvals [26]. Concurrently, nanobodies—small, stable antibody fragments derived from camelids—are gaining traction for their superior tissue penetration and unique epitope recognition [26]. Underpinning all these advancements is the transformative role of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning, which are revolutionizing antibody discovery and engineering by predicting structures, optimizing properties, and generating novel candidates de novo, thereby dramatically reducing development timelines and costs [26] [30].

In conclusion, understanding the fundamental distinctions between monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies, along with their appropriate labeling strategies, is a cornerstone of experimental design in immunochemistry. Monoclonal antibodies offer unparalleled specificity and consistency, making them ideal for targeted therapies and quantitative assays. Polyclonal antibodies provide robust signal amplification and versatility, suited for antigen capture and detection of denatured targets. The ongoing innovation in antibody formats, production methods, and conjugation technologies promises to further empower researchers and clinicians, continuing to drive progress in biomedical science and personalized medicine.

Immunodetection methods form the cornerstone of modern biomedical research and diagnostic development. Among these, direct and indirect detection strategies represent two fundamental approaches, each with distinct advantages and limitations in sensitivity, simplicity, and application suitability. This technical review provides a comprehensive comparison of these methodologies, examining their underlying principles, procedural workflows, and performance characteristics. Within the framework of immunochemistry principles, we analyze how researchers and drug development professionals can strategically select between these methods based on experimental requirements, focusing specifically on their differential signal amplification capabilities and operational complexity. The article incorporates detailed experimental protocols, quantitative performance data, and practical implementation guidelines to facilitate optimal method selection for various research scenarios.

Immunodetection methodologies leverage the specific binding between antibodies and antigens to identify and quantify biological molecules of interest. These techniques have become indispensable tools in research laboratories, clinical diagnostics, and drug development pipelines. The fundamental distinction between direct and indirect detection approaches lies in the configuration of the detection system, particularly in how the signal-generating moiety is incorporated into the assay architecture [31] [32]. Direct detection methods utilize primary antibodies that are directly conjugated to a detection label (enzyme, fluorophore, etc.), while indirect methods employ an unlabeled primary antibody followed by a labeled secondary antibody that recognizes the primary antibody [33] [34].

The choice between these approaches significantly impacts multiple experimental parameters, including sensitivity, specificity, time requirements, and cost-effectiveness. Understanding the core principles and mechanistic differences between these methods is essential for optimizing experimental design in immunochemistry applications [35]. This review systematically examines both methodologies, providing a technical foundation for researchers to make informed decisions based on their specific project requirements, whether for basic research, assay development, or diagnostic applications.

Fundamental Principles and Methodologies

Core Principles of Direct Detection

Direct detection methods operate on a straightforward principle: a single incubation step with a primary antibody that is directly conjugated to a detection molecule [33]. This configuration creates a direct physical link between the antigen-binding site and the signal-generating moiety, resulting in a simplified experimental workflow. In this approach, the labeled primary antibody binds specifically to the target antigen, and the resulting complex can be immediately visualized or quantified without additional binding steps [34].

The conceptual simplicity of direct detection translates into several practical advantages. The method involves fewer procedural steps, reducing total hands-on time and potential sources of error [33]. With only one antibody required, there is minimal risk of cross-reactivity with non-target proteins, leading to reduced background signal in many applications [35]. Additionally, the streamlined protocol makes direct detection particularly suitable for multiplexing experiments, where multiple targets are detected simultaneously using different conjugated primary antibodies with distinct labels [33].

Core Principles of Indirect Detection

Indirect detection employs a two-tiered antibody system consisting of an unlabeled primary antibody that specifically binds the target antigen, followed by a labeled secondary antibody that recognizes the constant region of the primary antibody [35] [34]. This layered approach introduces a signal amplification mechanism absent in direct detection, as multiple secondary antibodies can bind to a single primary antibody, dramatically increasing the signal output [33].

The signal amplification inherent in indirect detection significantly enhances sensitivity, making it particularly advantageous for detecting low-abundance targets [34]. This methodology also offers greater flexibility and cost-effectiveness, as a single conjugated secondary antibody can be used with various primary antibodies from the same host species [33]. This universality reduces the need for multiple labeled primary antibodies, expanding experimental possibilities without proportionally increasing reagent costs [32]. The indirect approach does, however, introduce additional complexity to the experimental workflow and requires careful optimization to minimize non-specific binding [34].

Figure 1: Comparative Workflows of Direct and Indirect Detection Methods. Direct detection requires fewer steps with only primary antibody incubation, while indirect detection involves sequential primary and secondary antibody incubations with additional wash steps, providing signal amplification but increased complexity.

Comparative Analysis: Sensitivity and Simplicity

The strategic selection between direct and indirect detection methods requires careful consideration of their relative performance characteristics, particularly regarding sensitivity and operational simplicity. The table below summarizes the core advantages and disadvantages of each approach across multiple experimental parameters:

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Direct and Indirect Detection Methods

| Parameter | Direct Detection | Indirect Detection |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Lower (limited signal amplification) | Higher (significant signal amplification via multiple secondary antibodies) [33] [34] |

| Simplicity | Higher (fewer steps, shorter protocols) [33] | Lower (additional incubation and wash steps required) [33] |

| Time Requirements | Shorter (single incubation step) [33] | Longer (multiple incubation steps) [33] [34] |

| Cost Considerations | Higher (conjugated primary antibodies more expensive) [33] | Lower (inexpensive secondary antibodies work with multiple primaries) [33] |

| Flexibility | Lower (each target requires specific conjugated primary) [34] | Higher (same secondary antibody works with multiple primaries from same host) [33] |

| Background Signal | Generally lower (fewer non-specific binding opportunities) [33] | Potentially higher (risk of secondary antibody cross-reactivity) [33] [34] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Simplified (minimal species cross-reactivity concerns) [33] | Complex (requires primary antibodies from different species) [33] |

| Antigen Conservation | Better (fewer processing steps) | Reduced (extended processing may affect antigen integrity) |

| Optimization Requirements | Lower (fewer variables to optimize) | Higher (both primary and secondary antibodies require optimization) |

The sensitivity advantage of indirect detection stems from its inherent signal amplification mechanism. Each primary antibody provides multiple epitopes for secondary antibody binding, with each secondary antibody typically carrying several reporter enzymes or fluorophores [35]. This multi-layer amplification can increase signal intensity by an order of magnitude or more compared to direct methods, making indirect detection particularly valuable when working with low-abundance targets or when maximal detection sensitivity is required [34].

Conversely, direct detection offers significant advantages in procedural simplicity and time efficiency. The single incubation step reduces total experimental time and minimizes potential error introduction [33]. The absence of secondary antibodies eliminates concerns about species cross-reactivity, which is particularly beneficial in multiplexing experiments where multiple protein targets are simultaneously detected using different conjugated primary antibodies [35]. This streamlined approach also typically yields lower background signal since fewer reagents are employed, reducing opportunities for non-specific binding [33].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Detailed Protocol for Direct ELISA

The direct ELISA format provides a straightforward approach for antigen detection and quantification. The following protocol outlines the key steps for implementing this methodology:

Plate Coating: Dilute the antigen of interest in carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (50 mM, pH 9.6) to an appropriate concentration. Add 100 μL/well to a 96-well microtiter plate and incubate overnight at 4°C [31].

Blocking: Remove the coating solution and wash the plate three times with PBS-T (phosphate-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween-20). Add 200 μL/well of blocking buffer (typically 1-5% BSA or non-fat dry milk in PBS) and incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature [31].

Primary Antibody Incubation: Prepare the enzyme-conjugated primary antibody in blocking buffer at the predetermined optimal dilution. Add 100 μL/well to the plate after washing three times with PBS-T. Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature [31] [34].

Signal Detection: Wash the plate three times with PBS-T. Add 100 μL/well of appropriate enzyme substrate. For horseradish peroxidase (HRP), use TMB substrate, which produces a blue color that turns yellow after stopping with acid. For alkaline phosphatase (AP), use pNPP substrate, which produces a yellow color [31].

Signal Measurement: Stop the reaction at the optimal time point (typically 15-30 minutes) by adding stop solution (e.g., 1M H₂SO₄ for TMB). Measure the absorbance at the appropriate wavelength (450 nm for TMB, 405 nm for pNPP) using a microplate reader [31].

Detailed Protocol for Indirect Immunofluorescence

Indirect immunofluorescence leverages the signal amplification properties of the indirect method for enhanced sensitivity in cellular localization studies:

Sample Preparation: Culture cells on sterile glass coverslips or use tissue cryosections. Fix samples with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 minutes at room temperature. Permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 minutes if intracellular targets are being detected [35].

Blocking: Incubate samples with blocking buffer (typically 1-5% BSA in PBS with 0.05% Tween-20) for 30-60 minutes at room temperature to reduce non-specific binding [35].

Primary Antibody Incubation: Dilute the unlabeled primary antibody in blocking buffer to the appropriate concentration. Apply to samples and incubate in a humidified chamber for 1-2 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C for enhanced specificity [35].

Secondary Antibody Incubation: Wash samples three times with PBS-T (5 minutes per wash). Apply fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488, Cy3) diluted in blocking buffer. Incubate for 45-60 minutes at room temperature in the dark [35].

Nuclear Counterstaining and Mounting: Wash samples three times with PBS-T. Optional: incubate with DAPI (1 μg/mL) for 5 minutes to stain nuclei. Wash with PBS and mount coverslips onto glass slides using antifade mounting medium [35].

Imaging and Analysis: Visualize using a fluorescence microscope with appropriate filter sets. Capture images using consistent exposure settings across experimental conditions for quantitative comparisons [35].

Detection Labels and Reagent Systems

The selection of appropriate detection labels is critical for optimizing both direct and indirect detection methodologies. Different labels offer distinct advantages depending on the specific application requirements and detection instrumentation available:

Table 2: Common Detection Labels and Their Applications

| Label Type | Examples | Primary Applications | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymatic | Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP), Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) | ELISA, Western Blot, Immunohistochemistry [31] [33] | Signal amplification through enzyme-substrate reaction, colorimetric or chemiluminescent detection [31] |

| Fluorescent | FITC, Alexa Fluor series, Cy dyes [35] | Immunofluorescence, Flow Cytometry, Fluorescent Western Blot [35] [33] | Direct signal detection, multiplexing capability, requires specific excitation/emission filters [35] |

| Biotin | Biotinylated antibodies | ELISA, Western Blot, Immunohistochemistry [33] | Secondary amplification with enzyme-streptavidin conjugates, extremely high sensitivity |

| Luminescent | Luciferase, Acridinium esters | High-sensitivity ELISA, Automated immunoassay systems [32] | Very high sensitivity, broad dynamic range, specialized instrumentation required |