Navigating IHC Assay Validation: A Comprehensive Guide to CLIA Requirements and Best Practices

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a current and actionable guide to Immunohistochemistry (IHC) assay validation within the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) framework.

Navigating IHC Assay Validation: A Comprehensive Guide to CLIA Requirements and Best Practices

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a current and actionable guide to Immunohistochemistry (IHC) assay validation within the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) framework. It covers foundational regulatory concepts, step-by-step methodological protocols for assay setup, strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing performance, and essential validation procedures for compliance. The content synthesizes the latest guidelines, including the 2024 CAP update and 2025 CLIA regulatory changes, to offer a complete resource for developing robust, reliable, and clinically actionable IHC assays.

Understanding the IHC and CLIA Regulatory Landscape: A Foundation for Validated Assays

Defining IHC Assay Validation and Verification in a Clinical Context

In clinical diagnostics and therapeutic decision-making, Immunohistochemistry (IHC) serves as a critical bridge between cellular morphology and specific protein identification. The clinical utility of any IHC assay, however, is entirely dependent on the rigorous assessment of its performance characteristics. Within a regulated clinical laboratory environment, this assessment is formalized through two distinct but related processes: validation and verification. Validation applies to laboratory-developed tests (LDTs) and entails a comprehensive establishment of performance specifications. In contrast, verification is the process of confirming the stated performance characteristics of a U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-cleared or approved assay within one's own laboratory setting [1] [2]. Adherence to these processes is mandated under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) of 1988, which set the federal standards for all laboratory testing in the United States [1] [3]. The College of American Pathologists (CAP) has further elaborated on these requirements through evidence-based guidelines, the most recent update of which was published in February 2024, ensuring that laboratory practices evolve to meet new challenges and incorporate the latest evidence [1] [4]. This guide objectively compares the performance requirements for different types of IHC assays within this regulatory framework, providing the experimental data and protocols essential for researchers and drug development professionals.

Regulatory Framework and Key Definitions

The foundation of clinical IHC testing is built upon a clear understanding of the regulatory landscape and its specific terminology. Compliance is not optional; it is a prerequisite for patient testing.

CLIA Requirements: CLIA regulations establish the baseline federal standards that all clinical laboratories must follow to ensure the accuracy, reliability, and timeliness of patient test results. While CLIA mandates that laboratories must validate/verify the performance characteristics of all assays before reporting patient results, it does not typically prescribe the detailed methods for doing so [1] [3].

CAP Guidelines: The College of American Pathologists provides detailed, evidence-based guidelines that laboratories use to satisfy CLIA requirements. The 2024 update to the "Principles of Analytic Validation of Immunohistochemical Assays" harmonizes and clarifies previous recommendations, offering a robust framework for laboratories [1] [4]. It is important to note that while these guidelines represent best practices, CAP-accredited laboratories must comply with the current edition of the Laboratory Accreditation Program (LAP) Checklist, which may not immediately incorporate all new guideline recommendations [1].

Key Definitions:

- Validation: The comprehensive process used by a laboratory to establish the performance characteristics of a laboratory-developed test (LDT) before it is used for patient testing. This includes defining analytical sensitivity, specificity, precision, and reportable range [2].

- Verification: The process of confirming that a previously validated or FDA-cleared/approved assay performs as expected within the laboratory's own environment. The extent of verification is generally less extensive than a full validation [5] [2].

- Analytic Validation: This focuses on proving the assay itself reliably detects the target antigen. It answers the question, "Does the test work?" This is distinct from clinical validation, which determines the test's ability to predict a clinical outcome or response to therapy.

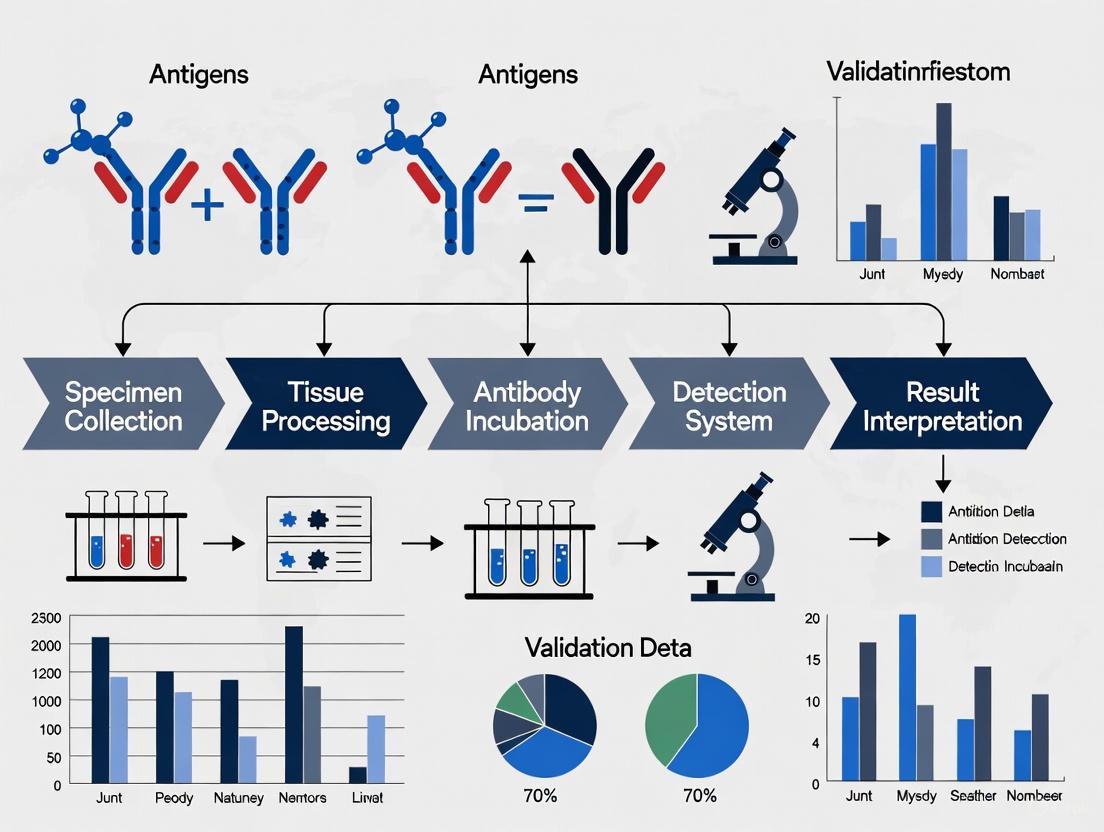

The following workflow diagram outlines the key decision points and processes for IHC assay validation and verification as per current guidelines:

Comparative Performance Data for IHC Assays

The CAP guidelines provide specific, quantitative requirements for the initial validation and verification of IHC assays. These requirements vary based on the assay type and its clinical application. The table below summarizes the key performance criteria for different assay categories.

Table 1: Summary of Analytic Validation and Verification Requirements from CAP Guidelines

| Assay Category | Minimum Case Requirements | Target Concordance | Key Considerations & Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory-Developated Non-Predictive Assays [2] | 10 positive and 10 negative cases | ≥90% overall concordance | Validation set should include high and low expressors and span the expected range of clinical results. |

| Laboratory-Developed Predictive Marker Assays [2] | 20 positive and 20 negative cases | ≥90% overall concordance | Applies to all predictive markers, harmonizing previous varying requirements for ER, PR, HER2. |

| FDA-Cleared/Approved Predictive Marker Assays [2] | Follow manufacturer's instructions; if none, use 20 positive and 20 negative cases | ≥90% overall concordance | Applies to unmodified FDA-approved/cleared assays. |

| Predictive Assays with Distinct Scoring Systems (e.g., PD-L1, HER2) [1] [2] | 20 positive and 20 negative cases per assay-scoring system combination | ≥90% overall concordance | Each unique antibody clone and scoring system combination must be separately validated. |

| IHC on Cytology Specimens with Alternative Fixation [1] [2] | 10 positive and 10 negative cases per fixation method | ≥90% overall concordance | Required for specimens not fixed identically to initial validation tissues (e.g., alcohol-fixed smears, cell blocks). |

A pivotal update in the 2024 guideline is the harmonization of the minimum concordance threshold to 90% for all IHC assays, including predictive markers like estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER2 performed on breast carcinoma, superseding previous differing thresholds [4]. Furthermore, the guideline introduces a strong recommendation for the separate validation of each unique antibody clone and scoring system combination for complex predictive markers like PD-L1 and HER2, which may employ different scoring criteria based on tumor site or type [1] [6].

Experimental Protocols for Validation Studies

Core Validation Study Design and Comparators

A fundamental component of validation is designing a study that robustly compares the new assay's performance against a reliable standard. The CAP guideline provides a list of acceptable comparators, ordered here from most to least stringent [1]:

- Cell Line Calibrators: Comparison to IHC results from cell lines with known protein quantities.

- Orthogonal Methods: Comparison with a non-immunohistochemical method (e.g., flow cytometry, fluorescent in-situ hybridization).

- External Laboratory Testing: Comparison with results from testing the same tissues in another laboratory using a validated assay.

- Prior Testing in Same Lab: Comparison with results from prior testing of the same tissues with a validated assay within the same laboratory.

- Clinical Trial Laboratory: Comparison with results from a laboratory that performed testing for a clinical trial.

- Antigen Localization: Comparison with the expected architectural and subcellular localization of the target antigen.

- Published Clinical Trials: Comparison against percent positive rates documented in published clinical trials.

- Proficiency Testing Challenges: Comparison with previously graded tissue challenges from a formal proficiency testing program.

Protocol for Validating Loss-of-Protein Expression Assays

Assays designed to detect the loss of protein expression, such as those for Succinate Dehydrogenase B (SDHB) and H3K27me3, present unique technical challenges during optimization and validation. The standard protocols optimized for detecting protein presence may not be suitable for interpreting loss of expression [7].

- Objective: To establish an IHC protocol that reliably distinguishes true loss of protein expression from weak or heterogeneous staining in tumor cells, while maintaining robust staining in internal positive control tissues.

- Methodology:

- Tissue Selection for Validation: Include known positive cases (with normal tissue serving as internal control), known negative cases (with confirmed genetic mutations leading to protein loss), and challenging cases with potential heterogeneous or "intermediate" staining patterns [7].

- Antibody Protocol Calibration: Titrate antibody dilution and antigen retrieval conditions to achieve optimal signal-to-noise ratio. The goal is a protocol that produces intense, specific staining in internal control elements (e.g., non-neoplastic cells, blood vessels) while showing definitive absence of staining in tumor cells of known negative cases. Avoid protocols that yield weak staining in controls, as this can make loss of expression in tumors difficult to distinguish [7].

- Platform Comparison: Run the validation set on different autostainer platforms if available, as staining results, particularly for heterogeneous markers, can vary significantly between instruments [7].

- Microscopic Analysis and Interpretation: Multiple pathologists should review the stained slides, focusing on the stark contrast between internal positive controls and the tumor. "Intermediate" staining patterns (weak or heterogeneous) should be noted and used to refine the diagnostic threshold [7].

- Key Experimental Controls:

- Positive Control Tissue: Tissue with known protein expression and reliable internal control elements.

- Negative Control Tissue: Tissue with a confirmed genetic alteration causing protein loss.

- Technical Control: Omission of the primary antibody to confirm absence of non-specific signal from the detection system.

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Successful IHC validation is contingent upon the use of well-characterized reagents and materials. The following table details essential components and their functions in the validation process.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for IHC Validation

| Item | Function in Validation | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Antibodies | Specifically binds to the target antigen of interest. | Clone specificity is critical. Switching clones requires full revalidation; changing vendor for the same clone requires a smaller verification [5] [2]. |

| Control Tissue Microarrays (TMAs) | Contain multiple positive and negative tissue specimens on a single slide for efficient validation. | Must include tissues with varying expression levels (high, low, negative) and should represent the intended clinical use cases [2]. |

| Antigen Retrieval Solutions | Unmask hidden epitopes altered by tissue fixation. | Changes in retrieval method (e.g., pH, buffer, heat platform) require extensive verification to ensure consistent results [5] [2]. |

| Detection System | Visualizes the antibody-antigen complex, typically using enzymatic reactions (e.g., HRP). | Changing the detection system requires verification with a sufficient number of cases to ensure performance is maintained [5]. |

| Cell Line Calibrators | Provide a standardized source of material with known antigen expression levels. | Serves as the most stringent comparator for validation study design [1]. |

| Automated Staining Platforms | Provide standardized and reproducible assay conditions. | Validation should account for platform-specific performance. Changing platforms requires verification [5] [2]. |

Navigating Verification for Modified IHC Procedures

Laboratories often need to modify existing IHC assays. The CAP guideline provides a pragmatic framework for the verification process, distinguishing between minor and major changes. The following diagram illustrates the decision-making pathway and corresponding actions for common procedural modifications.

As outlined in the pathway, the extent of verification required is proportional to the significance of the change [5] [2]:

- Minor Changes (Verification with 2 positive & 2 negative cases):

- Antibody dilution

- Antibody vendor (for the same clone)

- Incubation or retrieval times (with the same method)

- Major Changes (Verification with sufficient cases to ensure consistency):

- Fixative type

- Antigen retrieval method (e.g., change in pH, different buffer, different heat platform)

- Detection system

- Tissue processing or automated testing equipment

- Environmental conditions (e.g., laboratory relocation, water supply)

- Critical Change (Requires Full Revalidation):

- Changing the antibody clone

Within the clinical context, the rigorous processes of IHC assay validation and verification are non-negotiable prerequisites for ensuring diagnostic accuracy and patient safety. The updated 2024 CAP guidelines provide a clear, harmonized framework for laboratories, emphasizing a 90% minimum concordance for all assays, separate validation for complex predictive markers with multiple scoring systems, and specific guidance for cytology specimens and assay modifications. For researchers and drug developers, a deep understanding of these requirements is not merely about regulatory compliance; it is the foundation upon which reliable, reproducible, and clinically impactful IHC data is built. By adhering to these structured protocols and utilizing the appropriate reagents and controls, laboratories can ensure their IHC assays perform as intended, directly supporting precise therapeutic decision-making and advancing the field of personalized medicine.

Core CLIA Requirements for Laboratory-Developed Tests (LDTs) and FDA-Cleared Assays

For researchers and drug development professionals, navigating the regulatory landscape for immunohistochemistry (IHC) assays is fundamental to ensuring reliable and reproducible biomarker data. The U.S. regulatory framework primarily involves two distinct pathways: the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) clearance or approval process [3]. CLIA establishes quality standards for all laboratory testing performed on human specimens, focusing on the analytical validity of the testing process itself, regardless of whether the test is a laboratory-developed test (LDT) or an FDA-cleared assay [8]. In contrast, the FDA regulates commercial in vitro diagnostic (IVD) products, assessing their safety and effectiveness before they are marketed [8].

Understanding the distinction between LDTs and FDA-cleared assays is critical. An LDT is a test that is developed, validated, and used within a single laboratory [8]. These tests are crucial for personalized medicine, especially for novel biomarkers where no commercial test exists. They are validated under CLIA regulations, with specific analytical performance characteristics established by the laboratory director. An FDA-cleared or approved assay is a commercial product that has undergone rigorous FDA review to demonstrate its safety and effectiveness for its intended use [3]. When a laboratory introduces such a test, it must perform a verification process to confirm the manufacturer's claims under its own CLIA-certified conditions [1] [2]. The core distinction lies in the regulatory focus: CLIA ensures the quality of the laboratory's testing process, while FDA oversight for IVDs ensures the safety and effectiveness of the commercial test product itself.

Comparative Analysis of Core CLIA Requirements

The validation and verification requirements for IHC assays under CLIA differ significantly between LDTs and FDA-cleared tests, primarily in scope, sample size, and performance benchmarks. The table below summarizes the key requirements based on the latest College of American Pathologists (CAP) guidelines.

Table: Core CLIA Validation and Verification Requirements for IHC Assays

| Requirement | Laboratory-Developed Tests (LDTs) | FDA-Cleared/Approved Assays |

|---|---|---|

| General Principle | Must undergo full analytic validation before reporting patient results [1] [2]. | Must undergo analytic verification to confirm manufacturer's stated performance [1] [2]. |

| Overall Concordance | Must achieve at least 90% overall concordance with the comparator method [2]. | Must achieve at least 90% overall concordance with the expected results [2]. |

| Non-Predictive Markers | Minimum of 10 positive and 10 negative tissue cases [2]. | Follow manufacturer's instructions; if none, minimum of 20 positive and 20 negative tissues is recommended [2]. |

| Predictive Markers | Minimum of 20 positive and 20 negative tissue cases [2]. | Follow manufacturer's instructions; if none, minimum of 20 positive and 20 negative tissues is recommended [2]. |

| Assays with Multiple Scoring Systems | Each assay-scoring system combination must be separately validated with 20 positive and 20 negative tissues [1] [2]. | Each assay-scoring system combination must be separately verified with 20 positive and 20 negative tissues [1] [2]. |

| Cytology Specimens (Alternative Fixatives) | Separate validation required; minimum of 10 positive and 10 negative cases recommended for each fixation method [1] [2]. | Not explicitly stated, but laboratories should ensure performance is verified for alternative fixatives if used. |

Key Considerations for Validation and Verification

- Validation Study Design: For LDTs, the CAP guideline outlines multiple comparator options for validation study design, listed here from most to least stringent: comparison to protein-calibrated cell lines; non-IHC methods (e.g., flow cytometry); testing in another validated lab; prior testing in the same lab; expected antigen localization; results from clinical trials; published positive rates; and formal proficiency challenges [1] [2].

- Revalidation Triggers: CLIA requires laboratories to confirm assay performance after specific changes. A full revalidation (equivalent to an initial validation) is required when the antibody clone is changed. Other changes, such as in antibody dilution, vendor (same clone), incubation times, fixative type, antigen retrieval method, detection system, or testing platform, require a sufficient number of tissues to be tested to ensure consistent performance [2].

- Personnel Qualifications: CLIA regulations set strict personnel standards for laboratory directors, technical consultants, and testing personnel. Recent updates, effective in 2025, have refined the definitions of qualified degrees and experience, generally requiring education in chemical, biological, or clinical laboratory science and experience obtained in a CLIA-compliant facility [9] [10].

Experimental Protocols for IHC Assay Validation

This section details standard experimental methodologies used to generate the validation data required for compliance with CLIA standards.

Standard Validation Protocol for a Predictive IHC LDT

The following protocol is aligned with CAP guidelines for validating a predictive, laboratory-developed IHC assay, such as HER2 or PD-L1 [2].

Objective: To establish the analytical validity of a new LDT for a predictive biomarker by determining its concordance with a validated comparator method.

Materials and Reagents:

- Tissue Selection: A minimum of 40 unique, de-identified FFPE tissue blocks (20 positive, 20 negative) that span the expected range of clinical results, including high and low expressors where appropriate [2]. Tissues must be processed with the same fixative and methods intended for clinical use.

- Primary Antibody: The antibody clone and detection system under validation.

- Comparator Method: The gold-standard method for comparison (e.g., a different validated IHC assay, FISH, or NGS) [1].

Methodology:

- Sectioning and Staining: Cut sections from all 40 FFPE blocks. Process all slides in a single batch using the fully defined LDT protocol to minimize run-to-run variation.

- Comparison Testing: Subject the same set of cases to the established comparator method, ideally within a short timeframe.

- Blinded Evaluation: A pathologist, blinded to the results of the comparator method, scores all slides from the LDT. A second pathologist should independently score a significant subset to assess inter-observer reproducibility.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the overall percent agreement, positive percent agreement, and negative percent agreement between the LDT and the comparator. The overall concordance must meet or exceed the 90% threshold to be acceptable [2].

Protocol for an Interlaboratory Concordance Study

Interlaboratory studies are critical for verifying the reproducibility of an assay, a key aspect of robust validation [3] [11].

Objective: To evaluate the consistency of IHC results for a specific biomarker across different laboratories using the same or different antibody assays.

Materials and Reagents:

- Common Tissue Set: A series of FFPE tissue samples with a range of biomarker expression levels (e.g., HER2-zero, HER2-low, HER2-positive).

- Standardized Protocols: Participating laboratories may use their established, validated protocols, including different antibody clones (e.g., A0485 vs. 4B5 for HER2) and staining platforms [11].

Methodology:

- Sample Distribution: Distribute the common tissue set to all participating laboratories.

- Independent Staining and Scoring: Each laboratory processes, stains, and scores the tissues according to their standard clinical protocols. Pathologists in each lab score the samples without knowledge of other labs' results.

- Data Consolidation and Analysis: A central team collects all scores and calculates the concordance rates between laboratories. Statistical analysis, such as Cohen's kappa for inter-rater reliability, is performed.

- Interpretation: The study can reveal assay-specific differences. For example, the cited study showed a significantly higher detection rate for HER2-low expression using the Ventana 4B5 assay compared to the Dako A0485 antibody [11].

Emerging Methodologies and AI in IHC Validation

Advanced computational approaches are revolutionizing IHC biomarker prediction and validation, offering paths to enhanced standardization.

AI-Assisted Biomarker Prediction Workflow

Artificial intelligence models, particularly those using dual-modality learning, show promise in improving the accuracy and objectivity of IHC interpretation [12].

Diagram: AI-Powered Biomarker Prediction from H&E and IHC

This workflow illustrates a dual-modality AI framework that integrates both H&E and IHC stained whole slide images to predict biomarker status with high accuracy (AUROC >0.96) [12]. The model extracts features from both image types, aggregates them, and generates a prediction that has demonstrated superior prognostic precision compared to standard biomarker assessments in some studies [12].

Experimental Protocol for AI Model Validation

Objective: To validate the performance of an AI tool in predicting a key biomarker (e.g., PD-L1) from H&E and IHC whole slide images.

Materials and Reagents:

- Dataset: A large, retrospective cohort of WSIs (H&E and matched IHC) with confirmed biomarker status determined by standard methods (e.g., PCR for MSI, IHC with CPS scoring for PD-L1) [12].

- Computational Resources: High-performance computing clusters with GPUs suitable for deep learning.

- Software: Image analysis pipelines (e.g., QuPath for tissue segmentation) and deep learning frameworks (e.g., PyTorch, TensorFlow).

Methodology:

- Data Preprocessing: Train pixel classification models to segment tissues from H&E and IHC WSIs. Extract smaller image patches from the segmented tissue regions [12].

- Model Training: Train a transformer-based model on the image patches to extract relevant features. Use a separate aggregation algorithm to combine patch-level features into a single slide-level prediction [12].

- Performance Evaluation: Evaluate the model's performance on a held-out test set of WSIs by calculating the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC), sensitivity, and specificity. Compare the AI-predicted biomarker status against the ground-truth clinical status.

- Clinical Correlation: Assess the clinical utility of the AI prediction by analyzing outcomes such as time-on-treatment and overall survival for patients treated with targeted therapies, comparing the stratification achieved by the AI model to that of conventional IHC [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for IHC Assay Development and Validation

| Item | Function in IHC Assay Validation |

|---|---|

| Primary Antibodies | Key reagent that binds specifically to the target antigen. Validation requires careful selection of clone, vendor, and optimal dilution [2] [11]. |

| Control Cell Lines | Cell lines with known protein expression levels used as calibrators; one of the most stringent comparators for validation [1] [2]. |

| FFPE Tissue Microarrays (TMAs) | Contain multiple tissue cores on a single slide, enabling high-throughput screening of antibody performance across many tissues during validation [12]. |

| Detection Kits | Reagent systems that generate a detectable signal from antibody-antigen binding; changing the detection system requires revalidation [2]. |

| Automated Staining Platforms | Instruments that standardize the staining process; changing platforms requires confirmation of assay performance [2] [11]. |

| Image Analysis Software | AI and digital pathology tools that provide quantitative, objective scoring of IHC staining, reducing inter-observer variability [13] [12]. |

In the field of diagnostic pathology and therapeutic development, Immunohistochemistry (IHC) assays serve as critical tools for detecting protein biomarkers in tissue samples. The accuracy and reliability of these assays are paramount, as they directly influence patient diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment decisions. Within the framework of the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA), two principal guideline systems govern the validation of IHC assays: the College of American Pathologists (CAP) "Principles of Analytic Validation of Immunohistochemical Assays" 2024 update and the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) standards, particularly ILA28. These guidelines provide complementary but distinct pathways to ensure that IHC assays perform with the precision, accuracy, and reliability required for clinical use. This guide objectively compares these foundational frameworks, examining their respective requirements, experimental approaches, and applications within the context of modern laboratory medicine and drug development.

Comparative Analysis: CAP 2024 Update vs. CLSI Standards

The CAP 2024 Guideline Update and CLSI standards represent two comprehensive but differently focused approaches to IHC assay validation. The table below summarizes their core characteristics and requirements for direct comparison.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of CAP and CLSI IHC Validation Guidelines

| Feature | CAP 2024 Guideline Update | CLSI ILA28 Standard |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Analytical validation of IHC assays for clinical use [1] | Quality assurance for the total test system, including design control and implementation [14] |

| Scope | Focused on analytical validation/verification processes | Covers the total product life cycle: discovery, design, development, verification, and validation [14] |

| Key Applications | Diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive markers; expanded guidance for cytology specimens and predictive markers with distinct scoring systems [1] | Diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive applications on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded material and cytological preparations [14] |

| Validation Cases (Predictive Markers) | 20 positive and 20 negative cases [15] | Not explicitly specified in search results; defers to laboratory director's judgment |

| Validation Cases (Non-predictive Markers) | 10 positive and 10 negative cases [15] | Not explicitly specified in search results; defers to laboratory director's judgment |

| Concordance Threshold | 90% for all IHC assays [1] | Not explicitly specified in search results |

| Cytology Specimen Validation | Minimum 10 positive and 10 negative cases for alternative fixatives [1] | Addresses cytological preparations but specific case numbers not detailed [14] |

| Regulatory Recognition | Informs CAP Laboratory Accreditation Program; not currently mandated in LAP checklist [1] | FDA-recognized consensus standard [14] |

Experimental Protocols for IHC Assay Validation

CAP 2024 Recommended Workflow

The CAP 2024 guideline outlines a structured process for bringing new IHC assays into clinical use, from initial feasibility assessment to ongoing maintenance [15]. This workflow encompasses pre-analytical, analytical, and post-analytical phases to ensure comprehensive validation.

Pre-Validation Investigation: Before validation begins, laboratories must conduct a thorough investigation documenting clinical utility, projected test volumes, cost-effectiveness, and resource availability. This includes literature review of clone-specific performance data from sources like NordiQC and consultation with ordering pathologists and clinicians [15].

Optimization Phase: For laboratory-developed tests (LDTs), this involves selecting an appropriate antibody clone, identifying tissues with known expression of the target antigen, and iteratively adjusting reaction conditions (dilution, incubation, pretreatment parameters) until optimal staining is achieved. FDA-cleared/approved assays typically skip this phase and are used according to manufacturer specifications [15].

Validation/Verification Execution: The validation study tests the assay against a predetermined number of known positive and negative cases. CAP recommends 20 positive and 20 negative cases for predictive markers and 10 each for non-predictive markers. For rare antigens, collaborative approaches or cell lines may be necessary [15].

Analysis and Acceptance Criteria: Results are analyzed for overall concordance, with a target threshold of 90% for all IHC assays. Discordant results are scrutinized to identify potential issues with assay sensitivity or specificity [1].

CLSI's Total Test System Approach

CLSI guideline ILA28 emphasizes a comprehensive "total test system" approach, ensuring quality across all phases of the assay lifecycle from design to implementation [14]. The standard provides guidelines for developing validated IHC assays with attention to pre-examination, examination, and post-examination processes to ensure clinical applicability.

Technical Challenges and Special Considerations

Validation of Assays for Loss of Protein Expression

IHC assays designed to detect loss of protein expression, such as Succinate Dehydrogenase subunit B (SDHB) and H3K27me3, present unique validation challenges. These require different optimization strategies compared to assays detecting protein overexpression [7].

- SDHB Validation Challenges: Antibody protocols must produce strong staining in internal controls to effectively distinguish true loss of expression in tumor cells. Suboptimal protocols can result in staining patterns in mutated tumors that are difficult to distinguish from retained expression [7].

- H3K27me3 Heterogeneous Staining: Some tumors, including malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNST), show heterogeneous staining, with results potentially varying between different autostainer platforms. This heterogeneity complicates protocol calibration and diagnostic interpretation [7].

- Tissue Selection for Validation: The choice of validation tissues is particularly critical for these assays. Establishing an optimal balance between analytical sensitivity and specificity during protocol optimization is essential for reliable performance [7].

Specimen-Specific Validation Requirements

The CAP 2024 update provides specific guidance for validating IHC assays on cytology specimens fixed in alternative fixatives, recognizing the variable sensitivity of IHC on such specimens compared to formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues. Laboratories must perform separate validations with a minimum of 10 positive and 10 negative cases for each alternative fixative type used [1].

Platform and Personnel Variability

The CAP guideline recommends that validation plans address potential variability from instruments and personnel. A robust strategy might include running validation sets on different instruments over several days, with each run performed by different laboratory personnel to ensure consistency across operational conditions [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful IHC assay validation relies on a comprehensive toolkit of reagents and materials. The table below details essential components and their functions in the validation process.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for IHC Assay Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Validation | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Antibodies | Specifically binds to target antigen for detection | Clone selection critical; consult NordiQC assessments and CAP proficiency testing data for performance characteristics [15] |

| Control Tissue Arrays | Contain multiple tissue types with known antigen expression on a single slide | Enable efficient validation with reduced reagent use; ideal for including range of expression levels [15] |

| Cell Line Calibrators | Contain known amounts of target protein | Serve as stringent comparators for validation study design; particularly valuable for rare antigens [1] |

| Antigen Retrieval Reagents | Unmask hidden epitopes altered by tissue fixation | Optimization of retrieval conditions (pH, time, method) is often necessary for LDTs [15] |

| Detection Systems | Amplify and visualize antibody-antigen interactions | Selection affects assay sensitivity and background; must be compatible with primary antibody [14] |

| Reference Standards | Provide predetermined expected results for comparison | Can include orthogonal testing methods (e.g., FISH, molecular), results from another laboratory, or published clinical trial data [1] |

Regulatory Pathways and Compliance Framework

CLIA Compliance and Beyond

While CLIA provides federal standards for all laboratory testing, it does not specify detailed methodologies for satisfying performance requirements for IHC assays [3]. Laboratories therefore rely on CAP and CLSI guidelines to demonstrate CLIA compliance. However, manufacturers seeking commercial approval for in vitro diagnostic (IVD) tests must follow more rigorous pathways through the FDA, which often requires studies exceeding basic CLIA requirements [3].

Comparison of US and EU Regulatory Requirements

The regulatory landscape for IHC assays differs significantly between the United States and European Union, affecting validation strategy for globally marketed products.

US Regulatory Pathway: In the United States, companion diagnostics (CDx) may be classified as either Class II or Class III devices, with approval processes involving Premarket Approval (PMA) submissions to the FDA. The FDA favors a modular PMA process with timelines of approximately 12-24 months, requiring compliance with 21 CFR Part 820 and Bioresearch Monitoring (BIMO) audits [3].

EU Regulatory Pathway: Under the In Vitro Diagnostic Regulation (IVDR), companion diagnostics are uniformly classified as Class C devices. The approval process involves submission of a technical dossier to a notified body, with typical timelines of 12-18 months for CE marking, and requires quality management system audits against ISO 13485 [3].

The CAP 2024 Guideline Update and CLSI ILA28 standard provide robust, complementary frameworks for IHC assay validation within CLIA requirements. The CAP guidelines offer specific, evidence-based recommendations for analytical validation with defined case numbers and concordance thresholds, particularly valuable for clinical laboratories implementing both predictive and non-predictive IHC assays. Meanwhile, CLSI standards provide comprehensive guidance covering the entire assay lifecycle, with emphasis on total quality management systems. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding both frameworks is essential for developing clinically reliable assays. The CAP guidelines serve as an immediate resource for validation protocols, while CLSI standards provide the foundation for quality systems supporting regulatory submissions. Together, these guidelines ensure that IHC assays meet the rigorous standards required for both diagnostic use and therapeutic development in an evolving precision medicine landscape.

The Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) regulations underwent their first major update in over three decades, with significant changes to personnel qualifications taking full effect in 2025 [16] [17]. These revisions establish more precise standards for laboratory directors and staff performing moderate- and high-complexity testing, directly impacting how laboratories approach immunohistochemistry (IHC) assay validation and daily operations. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding these updated requirements is essential for maintaining compliance while advancing diagnostic and therapeutic development.

The updated rules reflect a concerted effort to balance addressing healthcare workforce shortages with ensuring patient safety and test reliability [16]. Key modifications include refined educational requirements, new experience mandates, and expanded pathways for certain roles, all while eliminating previous equivalency provisions that allowed for greater interpretation [9] [18]. This guide provides a detailed comparison of the updated standards, offering clarity on qualification pathways for laboratory directors and staff within the context of modern laboratory practice and IHC validation requirements.

Updated Qualification Pathways for Laboratory Directors

Laboratory directors bear ultimate responsibility for all test operations, and the 2025 CLIA rules substantially redefine the qualification pathways for these critical roles [9] [16]. The updates create distinct requirements based on testing complexity and degree type, with an increased emphasis on documented specialized training and specific scientific disciplines.

Comparative Analysis of Director Qualifications

Table: CLIA 2025 Laboratory Director Qualification Pathways

| Position & Complexity | Degree Requirement | Key Experience Requirements | New Training Mandates | Grandfathering Provision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-Complexity Lab Director (Non-Physician) | Doctoral degree (PhD) in chemical, biological, or medical laboratory science [16] | 2 years of laboratory training/experience AND 2 years of experience directing/supervising high-complexity testing [16] | 20 continuing education (CE) hours in laboratory practice covering director responsibilities [16] | Yes, for individuals continuously employed in role since 12/28/2024 [18] |

| Moderate-Complexity Lab Director (Master's Degree) | Master's degree in chemical, biological, clinical, or medical laboratory science [9] | 1 year of laboratory training/experience AND 1 year of supervisory experience in nonwaived testing [16] | 20 CE hours covering director responsibilities [16] | Yes, for individuals continuously employed in role since 12/28/2024 [9] |

| Moderate-Complexity Lab Director (Bachelor's Degree) | Bachelor's degree in chemical, biological, or medical laboratory science [9] | 2 years of laboratory training/experience AND 2 years of supervisory experience in nonwaived testing [16] | 20 CE hours covering director responsibilities [16] | Yes, for individuals continuously employed in role since 12/28/2024 [9] |

Key Changes and Enforcement Discretion

A significant change requires non-physician directors of high-complexity laboratories to hold board certification from an HHS-approved board, such as the American Board of Bioanalysis (ABB) or American Board of Clinical Chemistry (ABCC) [18]. The previously available pathway using "equivalent qualifications" has been eliminated [9] [18].

While the new rules formally mandate 20 CE credit hours in laboratory director responsibilities for most pathways, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has announced it will not currently enforce this CE requirement through a temporary enforcement discretion [18]. This provides a transition period for current personnel, though future compliance is likely expected.

The updated regulations also specify that physical science degrees no longer automatically qualify individuals for director positions or other roles requiring a science degree [16]. CMS now recognizes only degrees in biological sciences, chemical sciences, or clinical/medical laboratory technology [9] [17].

Revised Requirements for Technical Consultants, Supervisors, and Testing Personnel

The updated CLIA regulations extend beyond director roles, significantly modifying qualifications for technical consultants, supervisors, and testing personnel [9] [16]. These changes create new pathways for some roles while restricting others, with important implications for laboratory staffing and workflow management.

Technical Consultants and Supervisors

Technical consultants (for moderate-complexity testing) and technical supervisors (for high-complexity testing) now have more structured qualification pathways. A notable expansion allows individuals with an associate degree in medical laboratory technology plus four years of lab training or experience in nonwaived testing to qualify as technical consultants for moderate-complexity testing [9] [16]. This change helps address workforce shortages while maintaining quality standards.

For high-complexity technical supervisors, the updated rules remove previous qualification mechanisms such as certification by the American Society of Cytology, requiring instead that candidates meet more standardized educational and experience benchmarks [9].

Testing Personnel and Military Training

The updated rules provide clearer equivalency standards for testing personnel with bachelor's degrees, specifying that 120 semester hours from an accredited institution can substitute for a degree if they include specific coursework in medical laboratory science, biology, and chemistry [9].

A significant permanent pathway now exists for military-trained laboratory technicians with the medical laboratory specialist occupational specialty to qualify as testing personnel for moderate- and high-complexity testing [16]. This formal recognition of military training helps create a pipeline for veterans to enter civilian laboratory roles.

Nursing Professionals and High-Complexity Testing

After receiving substantial feedback, CMS reversed its initial proposal that would have allowed individuals with a Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) to perform high-complexity testing without additional training [16] [17]. The final rule requires nurses to complete additional training in biological/chemical sciences and clinical lab science equivalent to an associate degree in laboratory science before performing high-complexity testing [16].

Practical Implications for IHC Assay Validation and Laboratory Workflow

The updated personnel qualifications directly impact how laboratories approach IHC assay validation and daily operations. Understanding the practical implications of these changes is crucial for maintaining compliance while ensuring efficient laboratory workflow and reliable test results.

Integration with IHC Validation Guidelines

The 2025 CLIA personnel requirements complement recent updates to IHC validation standards, particularly the College of American Pathologists (CAP) "Principles of Analytic Validation of Immunohistochemical Assays" guideline update released in early 2024 [1]. Laboratory directors overseeing IHC validation must now ensure that:

- Personnel involved in validation processes meet updated educational and training requirements [9] [16]

- Each assay-scoring system combination (e.g., HER2, PD-L1) is separately validated/verified [1]

- Validations for IHC performed on cytology specimens with alternative fixatives include at least 10 positive and 10 negative cases [1]

The harmonized 90% concordance requirement for all predictive marker IHC assays in the updated CAP guidelines aligns with the CLIA emphasis on standardized quality measures [1].

Modified Assay Verification Protocols

For laboratories modifying existing IHC procedures, the personnel changes coincide with simplified verification protocols for specific changes. When switching antibodies from different vendors while using the same clone, CAP guidelines recommend verification with only 2 known positive and 2 known negative cases rather than full re-validation [5]. This efficient protocol can be implemented by qualified technical staff under the supervision of appropriately credentialed directors.

Table: IHC Assay Modification Requirements Under CAP Guidelines

| Type of Modification | Verification Requirement | Personnel Oversight |

|---|---|---|

| Minor Changes: Antibody dilution, vendor (same clone), incubation/retrieval times (same method) [5] | Confirm performance with 2 known positive and 2 known negative cases [5] | Technical supervisor with updated CLIA qualifications [9] |

| Major Changes: Fixative type, antigen retrieval method, detection system, testing equipment [5] | Comprehensive validation with sufficient cases to ensure consistent performance [5] | Laboratory director meeting updated 2025 CLIA standards [16] |

Implementation Workflow and Compliance Strategy

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for implementing the 2025 CLIA personnel requirements in the context of IHC assay validation:

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for IHC Validation

Implementing proper IHC assay validation under the updated CLIA framework requires specific reagent systems and materials. The following solutions represent core components necessary for developing compliant IHC assays.

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for IHC Validation

| Reagent Solution | Primary Function in IHC Validation | Regulatory Compliance Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Primary Antibodies | Target antigen detection with defined specificity and sensitivity [5] | Must demonstrate 90% concordance for predictive markers; clone-specific verification simplifies process [1] [5] |

| Antigen Retrieval Buffers | Expose epitopes masked by formalin fixation [5] | Changes in retrieval method (pH, buffer) require more extensive verification [5] |

| Detection Systems | Amplify signal with minimal background noise [5] | Switching detection systems necessitates comprehensive re-validation [5] |

| Control Cell Lines | Provide known antigen expression levels for calibration [1] | Serves as stringent comparator for validation study design [1] |

| Reference Standards | Establish expected staining patterns and intensity [1] | Enables comparison against published clinical trial data [1] |

The 2025 CLIA personnel updates represent the most significant regulatory change in decades for laboratory operations, establishing more rigorous and specific qualification pathways for directors and staff. For professionals involved in IHC assay validation and drug development, these changes necessitate careful review of current personnel credentials, strategic planning for staffing needs, and integration with updated analytical validation guidelines from organizations like CAP.

While the new requirements create certain challenges for laboratories, particularly regarding board certification for high-complexity PhD directors and the elimination of physical science degrees as automatic qualifications, they also provide clearer pathways for military-trained personnel and technical consultants. The concurrent updates to IHC validation guidelines offer opportunities to streamline certain verification processes, especially when implementing minor methodological changes.

Successful navigation of this new landscape requires a proactive approach to compliance, including documentation of grandfathering status where applicable, strategic pursuit of board certifications, and development of comprehensive training programs that address both technical competencies and regulatory requirements. By integrating these updated personnel standards with robust analytical validation protocols, laboratories can maintain compliance while advancing the development of reliable diagnostic and therapeutic tools.

For researchers and drug development professionals navigating the complex landscape of In Vitro Diagnostic (IVD) development, understanding how regulatory bodies classify device risk is fundamental to clinical trial planning and regulatory strategy. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) classifies investigational IVDs used in clinical studies as either Significant Risk (SR) or Nonsignificant Risk (NSR), a determination that directly dictates the pathway for regulatory compliance [19] [20].

This classification is critical because it determines whether a manufacturer must obtain an Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) from the FDA before initiating clinical studies [21] [19]. SR device studies require an approved IDE application, subjecting them to full FDA oversight and more stringent regulatory requirements. In contrast, NSR device studies are subject to "abbreviated" IDE requirements and rely primarily on institutional review board (IRB) oversight [19]. This risk assessment is uniquely tied to the device's potential to harm research participants, focusing primarily on the sampling procedures required and the potential consequences of erroneous results [19].

Regulatory Framework and Key Definitions

The regulatory framework for IVDs is established under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, with IVDs defined as reagents, instruments, and systems intended for the diagnosis of disease or other conditions using specimens taken from the human body [21]. Like other medical devices, IVDs are subject to premarket and postmarket controls, and the FDA classifies them into Class I, II, or III based on the level of regulatory control needed to assure safety and effectiveness [21].

For clinical investigations, the key definitions guiding risk assessment are:

- Significant Risk (SR): A clinical investigation is deemed SR when it involves an investigational medical device that presents a potential for serious risk to the health, safety, or welfare of a participant [19]. SR determinations require an IDE submission to the FDA.

- Nonsignificant Risk (NSR): An investigational device that does not carry this potential for serious risk is classified as NSR [19]. NSR studies are subject to abbreviated IDE requirements.

The intended use and indications for use are primary drivers of the risk classification [20]. If an incorrect test result could lead to patient harm—such as a false negative causing a subject to miss a critical treatment—the IRB or FDA may consider the device SR, even if the sampling procedure itself is minimal risk [20].

Table 1: Key Regulatory Definitions for IVD Risk Assessment

| Term | Definition | Regulatory Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Significant Risk (SR) | Presents potential for serious risk to health, safety, or welfare of a participant [19] | Requires an approved Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) from FDA [19] |

| Nonsignificant Risk (NSR) | Does not carry potential for serious risk [19] | Subject to abbreviated IDE requirements; primary oversight by IRB [19] |

| Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) | Allows an investigational device to be used in a clinical study to collect safety and/or effectiveness data [21] | Permits device shipment for research without full compliance with commercial distribution requirements [21] |

Core Components of IVD Risk Assessment

Evaluation of Sampling Procedures

The first critical component in risk assessment involves analyzing the sampling procedures required to obtain specimens for the investigational IVD. If these procedures are performed solely for research purposes and present significant risk, the entire study is typically classified as SR [19].

Table 2: Risk Classification of Common IVD Sampling Procedures

| Typically Significant Risk (SR) Procedures | Typically Nonsignificant Risk (NSR) Procedures |

|---|---|

| Biopsy of a major organ [19] | Blood obtained via finger stick or simple venipuncture [19] |

| Sampling requiring general anesthesia [19] | Saliva collection and buccal swabs [19] |

| Placement of a blood access line into an artery or large vein [19] | Use of existing specimens (archival tissue, biorepository samples) [19] |

| Procedures that prolong standard of care surgery [19] | Use of otherwise-discarded remnant tissue from standard procedures [19] |

| Skin punch biopsies [19] |

It is crucial to note that patient population characteristics—including health status, comorbidities, and medications—can elevate the risk of typically NSR procedures, necessitating careful study-specific evaluation [19].

Impact of Invalid Test Results

When research does not involve SR sampling procedures, the assessment shifts to the potential harm from inaccurate test results. All investigational IVD clinical trials must consider the impact of returning results on participants' clinical care outside the trial [19].

- False Positive Results: May lead to misdiagnosis, unnecessary treatments, unneeded confirmatory testing, and psychological trauma if a participant erroneously believes they have a serious disease [19] [22].

- False Negative Results: Might cause participants to forego or delay needed treatment, with potentially serious health implications [19] [22].

The method of result return also affects risk. IVDs intended for home use may present greater risk than lab-based tests because lay users interpret results without professional training [19]. Furthermore, using investigational IVDs for treatment decisions in therapeutic product trials substantially increases their risk profile [3].

Special Considerations for Therapeutic Product Trials

Clinical trials investigating therapeutic products present additional risk considerations when they utilize investigational IVDs for participant selection, treatment arm assignment, safety monitoring, or outcome prediction [19]. In these contexts, the safety profile of the therapeutic agent itself becomes a significant factor in the risk determination, as its safety and effectiveness have not been fully established [19].

Key protection considerations include:

- Foregoing Established Treatments: Will IVD results lead participants to forego or delay treatments known to be effective? Risk increases when established treatments are available outside the clinical trial [19].

- Exposure to Safety Risks: Will IVD use expose participants to safety risks from the investigational therapeutic that exceed those of standard care? As potential side effects increase in severity, so does the impact of invalid results [19].

- Biomarker-Therapeutic Relationship: Is there a well-established link between the biomarker detected by the IVD and the investigational therapeutic? Using an IVD with unestablished clinical validity to enroll participants increases overall risk [19].

For companion diagnostics specifically, regulatory strategy must account for their classification as Class II or III devices in the U.S., requiring either Premarket Approval (PMA) or 510(k) clearance [3].

Risk Determination Protocols and Regulatory Pathways

The Risk Determination Process

Sponsors and sponsor-investigators have several pathways for obtaining formal risk determinations:

- Sponsor's Initial Assessment: The sponsor performs an initial risk determination based on the potential for harm to subjects, including risks associated with device use [19] [20].

- IRB Review and Determination: IRBs serve as FDA surrogates in device risk determinations. They review the sponsor's assessment and can agree or reclassify the study [19] [20]. If an IRB reclassifies an NSR study as SR, the sponsor must notify the FDA within five working days and submit an IDE application [20].

- FDA Q-Submission Process: The traditional way to obtain a formal device risk determination is through the Q-Submission process [19]. For therapeutic product trials conducted under an IND, sponsors can also contact their FDA program officer for help determining if an investigational IVD is SR [19].

- Dual 510(k) and CLIA Waiver Pathway: For certain devices, manufacturers may pursue a dual submission containing both a 510(k) and CLIA Waiver by Application, with the FDA providing substantive interaction within 90 days [23].

Study Risk Determination for IVDs in Therapeutic Trials

When an IVD assay is used for prospective stratification or clinical decision-making in therapeutic trials, a Study Risk Determination (SRD) is necessary to evaluate if an IDE is required [3]. Manufacturers can submit an SRD Q-submission to the FDA for an official determination, have the IRB assess risk as an FDA surrogate, include the assessment in a pre-IND briefing book, or simply assume significant risk and submit an IDE [3].

Table 3: Methodological Approaches to IVD Risk Determination

| Methodology | Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Risk Analysis | Identification of potential sources of error for the device [23] | Required for CLIA Waiver by Application; fundamental to all IVD risk assessment |

| Risk Evaluation & Control | Description of implemented mitigation measures and validation studies for failure alerts and fail-safe mechanisms [23] | Critical for demonstrating risk control in SRD submissions and IDE applications |

| Flex Studies | Demonstration of test system insensitivity to environmental and usage variations under stress conditions [23] | Particularly important for waived tests and point-of-care devices |

| Clinical Performance Studies | Studies designed to demonstrate insignificant risk of erroneous results in hands of intended users [23] | Required for all IVDs; design varies based on intended use and complexity |

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Regulatory Resources

| Resource | Function/Purpose | Application in IVD Risk Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Q-Submission Program | Formal process for obtaining FDA feedback on regulatory questions [21] [3] | Obtain formal device risk determination from FDA prior to study initiation [19] |

| Pre-Submission Meeting | Forum for sponsor and FDA to discuss proposed study designs [21] [23] | Align on appropriate designs for analytical validation studies and risk assessment [3] |

| ISO 20916:2019 | International standard for clinical performance studies using human specimens [22] [20] | Guidance on planning/conducting IVD clinical performance studies, including interventional designs [20] |

| CLIA Waiver Decision Summaries | Publicly available FDA reviews of successful waiver applications [24] | Understand evidence needed to demonstrate simple, low-risk device characteristics [24] |

| 21 CFR 812 | Investigational Device Exemption regulations [19] [20] | Defines boundaries for researching investigational devices in interstate commerce [20] |

Determining significant versus nonsignificant risk for IVDs is a critical, study-specific process that demands careful evaluation of sampling procedures and potential consequences of erroneous results. The regulatory pathway—and ultimately the timeline to market—depends heavily on this initial risk classification. As IVD technologies evolve and play increasingly prominent roles in therapeutic development, particularly in personalized medicine approaches, understanding these risk assessment principles becomes ever more essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. By systematically addressing both procedural risks and result impact concerns, and by engaging early with regulatory bodies through the available mechanisms, sponsors can navigate this complex landscape more efficiently while maintaining focus on patient safety.

Executing IHC Assay Validation: A Step-by-Step Protocol from Optimization to Go-Live

Within the rigorous framework of Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) research, the pre-validation investigation represents a critical, strategic phase that precedes formal analytical validation. This stage determines an assay's potential for success by systematically evaluating its foundational requirements: clinical utility, market demand, and necessary resources. For researchers and drug development professionals, a robust pre-validation assessment de-risks the subsequent, resource-intensive analytical validation process, which is mandated by CLIA regulations for any test used in patient diagnosis, treatment, or prevention [1] [3]. The 2024 update to the College of American Pathologists (CAP) guidelines emphasizes that while laboratories are not legally bound to follow these specific recommendations, adopting them is a best practice that significantly enhances the quality and safety of clinically important immunohistochemistry (IHC) assays [1]. This guide objectively compares methodologies for conducting this essential preliminary investigation, providing a data-driven foundation for project planning and go/no-go decisions in assay development.

Quantifying Clinical Utility: Methodologies and Comparative Data

Clinical utility is defined as a test's ability to influence clinical decision-making and improve patient outcomes or healthcare efficiency [25]. Establishing this utility is a prerequisite for securing coverage and reimbursement from payers [26]. The following section compares the primary methodologies used to generate evidence of clinical utility.

Comparative Analysis of Clinical Utility Assessment Methods

Table 1: Comparison of Methods for Assessing Clinical Utility

| Method | Key Feature | Best Use Case | Relative Cost & Timeline | Key Strength | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) with Virtual Patients [26] | Randomizes physicians to control/intervention arms; uses virtual patient vignettes. | Demonstrating change in physician behavior and diagnostic/treatment planning. | Lower cost; Shorter timeline (months). | Cost-effective; Measures proximal behavioral change. | Does not directly measure long-term patient outcomes. |

| Traditional Patient-Level RCT [25] [26] | The gold standard; randomizes patients to testing strategies. | Providing the highest level of evidence for regulatory and payer submissions. | Very high cost; Long timeline (years). | Directly measures impact on patient outcomes. | Prohibitively expensive and slow for many diagnostic companies. |

| Systematic Review [25] | Summarizes and pools data from existing published studies. | Early-stage assessment of a test's potential and known drawbacks. | Low cost; Variable timeline. | Comprehensive use of existing evidence. | Limited by the quality and scope of existing literature. |

| Decision Analysis [25] | Uses mathematical models to compare outcomes of different diagnostic strategies. | Informing trial design and estimating value when clinical data is sparse. | Moderate cost; Short timeline. | Models optimal use in clinical practice. | Relies on assumptions which may not hold true. |

| Expert Opinion [25] | Leverages the experience and knowledge of healthcare providers. | Gathering preliminary, real-world insights on test applicability. | Low cost; Short timeline. | Provides practical, clinical context. | Subjective and not considered high-level evidence. |

Experimental Protocol: Virtual Patient Randomized Controlled Trial

The virtual patient RCT is an emerging and efficient method for generating high-quality evidence of clinical utility. The detailed protocol, as implemented in multiple diagnostic studies, is as follows [26]:

- Physician Recruitment and Randomization: A nationally representative sample of board-certified physicians is recruited. Eligible physicians must have no prior experience with the new test. Participants are formally consented and then randomized into a control arm and one or more intervention arms.

- Baseline Assessment (Round 1): All physicians, in both control and intervention arms, care for an initial set of three virtual patient vignettes, known as Clinical Performance and Value (CPV) vignettes. These vignettes are developed by clinical experts to represent the intended use population and contain explicit, evidence-based scoring criteria (typically 40-66 criteria per case) across domains of care: history, physical exam, workup, and diagnosis plus treatment (DxTx).

- Intervention: In the interval between assessment rounds, physicians in the intervention arm receive educational materials about the new diagnostic test. In some study designs, a second intervention arm may be added that not only receives education but is also automatically provided with the test results for their patients in the second round.

- Post-Intervention Assessment (Round 2): All physicians care for a second set of three virtual patients. Intervention physicians have the option (or are required) to order the new test.

- Analysis: The primary outcomes are the changes in overall CPV score and, more specifically, the DxTx domain score between Rounds 1 and 2. A difference-in-difference analysis using multivariate linear regression is employed to compare the improvement in the intervention arm(s) versus the control arm. The study is typically powered to detect a clinically meaningful 3-5% change in CPV scores.

The workflow for this experimental design is standardized and can be visualized as follows:

Navigating the Validation and Regulatory Landscape

A successful pre-validation investigation must align with the regulatory pathway the assay will ultimately follow. The requirements for a laboratory-developed test under CLIA differ from those for a commercially distributed in vitro diagnostic (IVD) kit [3].

Comparative Analysis of Validation Tiers and Regulatory Pathways

Table 2: Comparison of Validation Tiers and Regulatory Pathways for IHC Assays

| Aspect | CLIA Laboratory-Developed Test [1] [3] | FDA-Cleared IVD Kit (US) [3] | CE-Marked IVD (EU) [3] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Governing Body | CMS & CAP (for accredited labs) | FDA (Center for Devices and Radiological Health) | Notified Body (under IVDR) |

| Primary Focus | Analytical validity within a single lab. | Analytical and clinical validity for broad, commercial use. | Analytical and clinical validity under EU risk classification. |

| Key Validation Guidance | CAP "Principles of Analytic Validation" (e.g., 90% concordance for predictive markers) [1]. | CLSI guidelines; Pre-submission meetings with FDA recommended. | IVDR; ISO 13485 (QMS); ISO 14971 (Risk Management). |

| Typical Sample Size for Initial Validation | Varies; e.g., 10 positive & 10 negative for alternative fixatives [1]. | Defined by CLSI guidelines; typically larger, multi-site studies. | Defined by IVDR and harmonized standards; similar to FDA. |

| Modification Process ("Verification") | Simplified verification for same antibody clone (e.g., 2 positive & 2 negative cases) [5]. | Often requires a new submission or supplemental data. | Requires technical documentation and assessment by Notified Body. |

| Risk Assessment for Clinical Trials | SRD (Study Risk Determination) or IRB assessment [3]. | IDE (Investigational Device Exemption) often required for significant risk. | Annex XIV submission to national competent authority [3]. |

The Pre-Validation Workflow: From Concept to Viability Assessment

Integrating the assessments of clinical utility, demand, and resources into a single, coherent pre-validation investigation is crucial. The following workflow provides a logical pathway for researchers to systematically evaluate an IHC assay's potential before committing to formal validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and materials are critical for conducting robust IHC pre-validation and validation studies. Their consistent quality is foundational to generating reliable data.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for IHC Assay Development

| Reagent / Material | Critical Function | Pre-Validation & Validation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Antibodies | Binds specifically to the target antigen of interest. | Clone specificity is paramount. Switching vendors for the same clone requires verification (e.g., 2 positive & 2 negative cases) [5]. |

| Antigen Retrieval Buffers | Unmasks hidden epitopes altered by tissue fixation. | pH, buffer composition, and retrieval method (e.g., heat platform) are critical variables. Changing the method requires extensive verification [5]. |

| Detection Systems | Visualizes the antibody-antigen binding. | Sensitivity and signal-to-noise ratio must be optimized and consistent. Changing the detection system triggers a full verification [5]. |

| Control Tissue Sections | Serves as positive and negative controls for assay performance. | Must include tissues with varying expression levels and known negatives. Sourcing a sufficient number of well-characterized controls is a major challenge [1] [5]. |

| Cell Lines | Used as calibrators or internal controls. | Cell lines with known protein expression levels provide a stringent comparator for validation study design [1]. |

A comprehensive pre-validation investigation is an indispensable strategic exercise in IHC assay development. By objectively comparing and implementing modern methodologies like virtual patient RCTs to assess clinical utility, and by clearly understanding the resource commitments for different regulatory pathways, researchers and drug developers can make data-driven decisions. This rigorous approach ensures that only the most promising assays, with a high probability of clinical adoption and commercial success, advance into the costly and formal analytical validation phase required by CLIA and other regulatory bodies.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) serves as a cornerstone technique in both research and diagnostic laboratories, playing a vital role in identifying biomarkers within tissue samples [3]. The reliability of IHC data, however, is critically dependent on the selection and validation of primary antibodies, with studies indicating that approximately 49% of commercially available antibodies fail validation procedures [27]. This high failure rate has significant scientific and financial implications, contributing to an estimated $800 million wasted annually on poorly performing antibodies and approximately $350 million lost in biomedical research due to irreproducible results [27]. Within clinical laboratories operating under Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) regulations, demonstrating analytic validity for IHC assays is not merely best practice but a fundamental requirement for accreditation and patient testing [1] [28].

The College of American Pathologists (CAP) emphasizes that validation ensures an IHC assay is reliable and reproducible for biomarker detection in clinical settings [1] [3]. The level of validation required correlates directly with the assay's intended purpose, with tests informing patient treatment decisions necessitating more robust validation than those designed for research purposes alone [3]. This guide provides a comprehensive framework for antibody and clone selection, leveraging established quality resources and vendor data to meet the exacting standards required for CLIA-compliant IHC assay validation.

Proficiency Testing and External Quality Assessment

External quality assessment (EQA) programs provide invaluable, real-world data on antibody performance across multiple laboratories and testing conditions. NordiQC (Nordic Immunohistochemical Quality Control) represents a premier EQA resource that aims to "promote the quality of immunohistochemistry and expand its clinical use by arranging schemes for immunohistochemical proficiency testing" [29]. Through its proficiency testing schemes, NordiQC provides participants with performance feedback and publishes recommended protocols, tissue controls, and technical parameter descriptions that laboratories can consult when selecting and validating antibodies [29]. The organization maintains strict independence from commercial interests, ensuring unbiased evaluation data [29].

Antibody Search Engines and Comparison Tools

Several specialized search engines facilitate the initial identification of available antibody clones targeting specific antigens:

- Biocompare, SelectScience, and NCBI antibody search portals allow researchers to find and compare antibodies from multiple vendors simultaneously, saving valuable time compared to visiting individual vendor websites [27].

- BD Biosciences' Clone Comparison Tool enables systematic comparison of antibody clones against the same antigen, presenting scientific details, qualified applications, and available formats in an easy-to-read table format [30].

- Human Cell Differentiation Molecules (HCDM) database provides information on clones characterized through international workshops, detailing which antibodies have been independently tested for specific CD markers [31].

Vendor-Supplied Validation Data

Reputable antibody vendors provide varying levels of validation data, though the completeness and quality of this information must be critically evaluated. When assessing vendor data, laboratories should look for:

- Complete, uncropped western blot images with specified protein loading amounts [27]

- Validation using multiple biologically relevant sample types or tissues [27]

- Demonstration of performance under fixation conditions matching the laboratory's intended use [1]

- Clear specification of the antibody clone and species reactivity [30] [27]

- Data generated using appropriate positive and negative controls [27]

Experimental Design for Antibody Clone Comparison

Establishing Comparison Criteria

When comparing antibody clones for the same target, laboratories should establish standardized evaluation criteria prior to testing. The following table outlines essential parameters for systematic clone comparison:

Table 1: Key Parameters for Antibody Clone Comparison

| Parameter | Assessment Method | Optimal Result |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Western blot with relevant cell lysates; IHC with knockout/knockdown controls | Single band at expected molecular weight; absence of staining in negative controls |

| Sensitivity | Titration series on known positive samples with expected antigen expression levels | Detect antigen at biologically relevant concentrations with minimal background |

| Optimal Dilution | Chessboard titration using a range of antibody concentrations | Highest dilution providing strong specific signal with minimal background |

| Inter-lot Variability | Parallel testing of different manufacturing lots | Consistent performance across lots |

| Platform Compatibility | Testing on different automated IHC platforms | Robust performance across platforms with minimal protocol adjustments |

| Fixation Compatibility | Testing on tissues fixed with different fixatives and fixation times | Consistent performance with intended fixation protocol |

Stepwise Validation Protocol

The CAP guidelines outline a structured approach for analytic validation of IHC assays [1] [28]. The following workflow provides a detailed protocol for comparing antibody clones during assay validation:

Figure 1: Systematic workflow for comparing antibody clones during IHC assay validation. The process begins with clear definition of assay requirements and proceeds through iterative testing phases to identify the optimal reagent.

Define Intended Use and Validation Requirements: Clearly establish whether the assay will be used for predictive, prognostic, or diagnostic purposes, as this determines the stringency of validation needed [3]. For predictive markers, the 2024 CAP guideline update harmonizes concordance requirements to 90% for all IHC assays [1].

Identify Available Clones and Resources: Utilize search engines and comparison tools to identify all commercially available clones against the target antigen [30] [27]. Consult NordiQC and published literature for performance data on specific clones.