Spike and Recovery Experiments for ELISA Validation: A Complete Guide to Principles, Methods, and Troubleshooting

This comprehensive guide details the critical role of spike and recovery experiments in validating Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) accuracy and reliability for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Spike and Recovery Experiments for ELISA Validation: A Complete Guide to Principles, Methods, and Troubleshooting

Abstract

This comprehensive guide details the critical role of spike and recovery experiments in validating Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) accuracy and reliability for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of assessing matrix interference, provides step-by-step methodological protocols for execution and data analysis, outlines systematic troubleshooting for common recovery issues, and explores integrative validation through dilutional linearity and parallelism studies. The article synthesizes established guidelines and current best practices to equip scientists with the knowledge to ensure their immunoassay data is fit-for-purpose in biomedical research and regulatory contexts.

Understanding Spike and Recovery: The Foundation of Reliable ELISA Data

Defining Spike and Recovery in the Context of ELISA Validation

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) provides a methodical quantification of specific analytes through antibody-analyte binding affinity and colorimetric development, serving as a fundamental tool in clinical and research laboratories [1]. However, the accuracy of this quantification can be compromised when the complex composition of biological samples interferes with the detection system. Spike and recovery experiments are therefore an essential validation component, determining whether a known amount of analyte can be accurately measured when introduced into a biological sample matrix [2] [3]. This process confirms the assay's accuracy by revealing if sample constituents affect antigen detection by the antibody, which could lead to either underestimation or overestimation of the true concentration [4].

The fundamental question addressed by spike and recovery is whether the percent recovery obtained from the standard diluent is identical to that obtained from the natural sample matrix [1]. When the sample matrix contains components that affect the assay response differently than the standard diluent, the recovered value will differ significantly from the expected concentration, indicating interference [2] [5]. Such interference can manifest from factors such as high or low pH, high protein or salt concentration, or presence of detergents or organic solvents, all known to interfere with ELISA quantification [3]. Conducting this assessment is therefore critical for researchers and drug development professionals to have confidence in their data quality and to qualify their assays in accordance with regulatory guidelines [3].

Core Concepts and Definitions

What is Spike and Recovery?

Spike and recovery involves introducing ("spiking") known amounts of a purified analyte into various sample types and measuring whether the "recovery" measurements are accurate when compared to the same spike in a standard diluent [2] [3]. The process quantitatively evaluates the effect of the sample matrix on the detection of the antigen by the antibody [4]. In a typical experiment, a known quantity of analyte is added to both the biological sample matrix (e.g., serum, plasma, urine) and a standard diluent (the solution used to prepare the standard curve) [2]. The assay is then run to measure the response of the spiked sample matrix compared to the identical spike in the standard diluent [2].

The recovery percentage is calculated using the formula:

% Recovery = (ConcentrationSpiked Sample - ConcentrationEndogenous) / ConcentrationControl Spike × 100% [5]

Where:

- ConcentrationSpiked Sample is the measured concentration of the sample after spiking

- ConcentrationEndogenous is the measured concentration of the endogenous analyte in the sample before spiking

- ConcentrationControl Spike is the measured concentration of the analyte spiked into the standard diluent [5] [4]

Interference: Over-Recovery and Under-Recovery

Interference occurs when components in the product formulation buffer cause inaccuracies in the ability of the assay to detect and quantify impurities, leading to either over-recovery or under-recovery [3].

- Under-recovery is more common and typically manifests as recovery percentages significantly below the acceptable range. This can be caused by matrix components that inhibit antibody binding, degradation of the analyte, adsorption to surfaces, or poor antibody affinity [3] [6].

- Over-recovery, though less common, occurs when recovery percentages exceed the acceptable range. This can result from matrix components that non-specifically enhance the signal or interact with the capture or detection antibody [3].

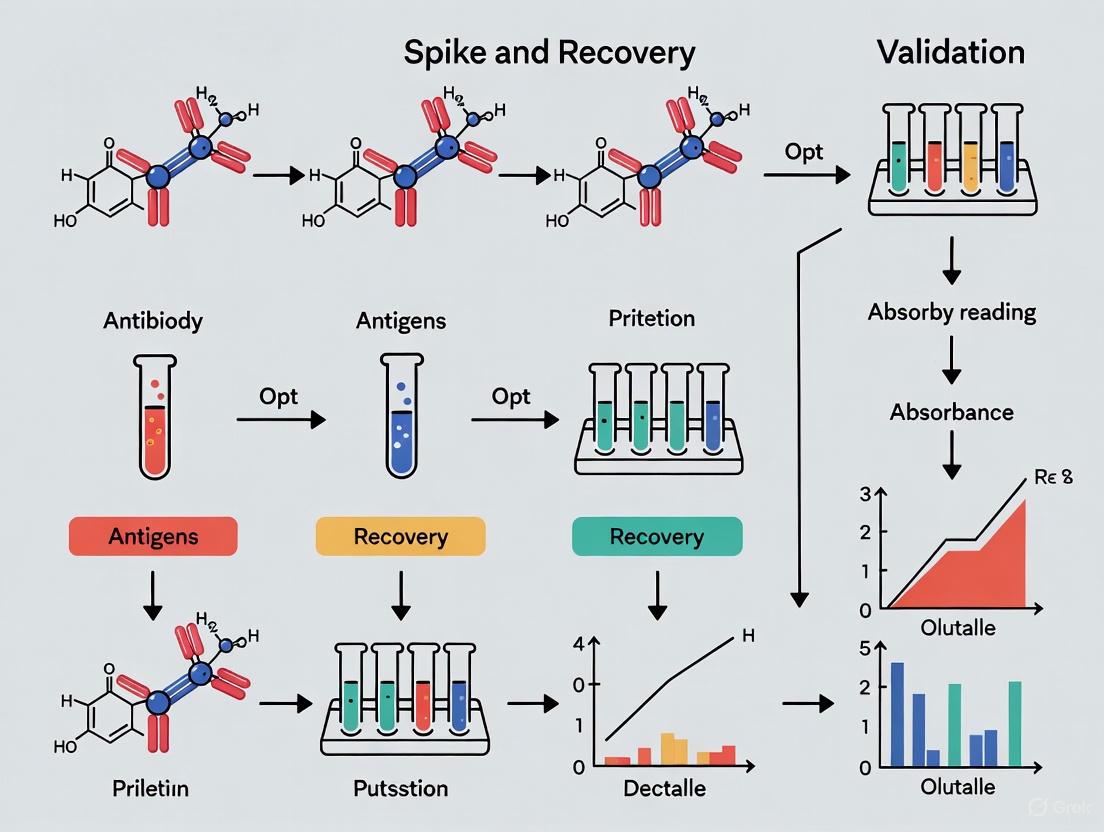

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow and potential interference points in a spike and recovery experiment:

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Step-by-Step Spike and Recovery Protocol

Performing a robust spike and recovery experiment requires systematic execution with appropriate controls. The following protocol provides a detailed methodology:

Sample Preparation:

Spike Solution Preparation:

- Prepare a concentrated stock solution of the purified analyte (recombinant protein or purified native protein) in the standard diluent [2] [3].

- The spike concentration should be selected to achieve 3-4 concentration levels covering the analytical range of the assay when added to the sample [3].

- Ensure the lowest spiked concentration is at least 2 times the Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) of the assay [3].

Experimental Setup:

Assay Execution:

Calculation and Analysis:

- Calculate the concentration of all samples using the standard curve [4].

- Subtract the endogenous contribution (measured from the control sample with zero standard) from the total measured concentration in the spiked sample [3].

- Calculate the percent recovery using the formula provided in Section 2.1 [5].

Linearity of Dilution Assessment

Linearity of dilution is closely related to spike and recovery and is often assessed simultaneously [2]. This experiment provides information about the precision of results for samples tested at different levels of dilution in a chosen sample diluent [2]. The protocol involves:

Traditional Method:

- Use a low-level sample containing a known spike of analyte or a sample with high endogenous levels of the analyte [2] [1].

- Prepare several serial dilutions (e.g., 1:2, 1:4, 1:8) of the sample in the chosen sample diluent [2] [5].

- Test all dilutions in the assay and calculate the observed concentration for each [2].

Alternative Method:

Interpretation:

- For each dilution, multiply the observed concentration by the dilution factor to obtain the normalized concentration [5].

- Calculate the percent recovery for each dilution: ((ConcentrationDiluted Sample / Dilution Factor) / ConcentrationUndiluted Sample) × 100% [5].

- Assess whether the normalized concentrations remain consistent across dilutions [2].

The relationship between spike and recovery and linearity of dilution assessment, along with their experimental workflows, is illustrated below:

Performance Standards and Acceptance Criteria

Quantitative Acceptance Criteria for Spike and Recovery

Establishing clear acceptance criteria is fundamental for interpreting spike and recovery results. The table below summarizes the performance standards from various sources and contexts:

Table 1: Acceptance Criteria for Spike and Recovery Experiments

| Source/Context | Acceptable Recovery Range | Notes & Applications |

|---|---|---|

| General Bioanalytical Guidelines [6] | 90–110% | Ideal range for most biological samples |

| Regulatory Guidelines (ICH, FDA, EMA) [3] | 75–125% | Applied for HCP ELISA and biopharmaceutical applications |

| Food Allergen Testing (AOAC) [7] | 50–150% | Acceptable for challenging food matrices when consistent |

| Commercial ELISA Kit Validation [8] | 80–120% | Typical range for commercial kit quality control |

| Research ELISA Applications [5] | 80–120% | Commonly cited range for research purposes |

Representative Spike and Recovery Data

The following table presents representative spike and recovery data for recombinant human IL-1 beta in nine human urine samples, demonstrating how results are typically compiled and analyzed:

Table 2: Experimental Spike and Recovery Data for Human IL-1 Beta in Urine Samples [2]

| Sample | No Spike (0 pg/mL) | Low Spike (15 pg/mL) | Medium Spike (40 pg/mL) | High Spike (80 pg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diluent Control | 0.0 | 17.0 | 44.1 | 81.6 |

| Donor 1 | 0.7 | 14.6 | 39.6 | 69.6 |

| Donor 2 | 0.0 | 17.8 | 41.6 | 74.8 |

| Donor 3 | 0.6 | 15.0 | 37.6 | 68.9 |

| Donor 4 | 0.0 | 15.1 | 36.9 | 67.8 |

| Donor 5 | 0.5 | 12.5 | 33.5 | 63.6 |

| Donor 6 | 0.0 | 14.0 | 33.5 | 68.7 |

| Donor 7 | 0.0 | 14.4 | 38.5 | 69.6 |

| Donor 8 | 7.1 | 16.3 | 41.4 | 69.5 |

| Donor 9 | 0.7 | 12.4 | 37.6 | 68.2 |

| Mean Recovery (± S.D.) | NA | 86.3% ± 9.9% | 85.8% ± 6.7% | 84.6% ± 3.5% |

Linearity of Dilution Performance Standards

For linearity of dilution experiments, the acceptance criteria are similarly strict. The normalized analyte concentrations (accounting for dilution factors) should remain consistent across different dilutions [5]. The percentage recovery for linearity is calculated as: ((ConcentrationDiluted Sample / Dilution Factor) / ConcentrationUndiluted Sample) × 100% [5]. Values between 80–120% generally demonstrate good assay linearity [5] [8].

The table below shows representative linearity of dilution data for human IL-1 beta in different sample matrices:

Table 3: Experimental Linearity of Dilution Data for Human IL-1 Beta [2]

| Sample | Dilution Factor (DF) | Observed (pg/mL) × DF | Expected pg/mL (neat value) | Recovery % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ConA-stimulated Cell Culture Supernatant | Neat | 131.5 | 131.5 | 100 |

| 1:2 | 149.9 | 114 | ||

| 1:4 | 162.2 | 123 | ||

| 1:8 | 165.4 | 126 | ||

| High-level Serum Sample | Neat | 128.7 | 128.7 | 100 |

| 1:2 | 142.6 | 111 | ||

| 1:4 | 139.2 | 108 | ||

| 1:8 | 171.5 | 133 | ||

| Low-level Serum Sample Spiked with Recombinant IL-1 Beta | Neat | 39.3 | 39.3 | 100 |

| 1:2 | 47.9 | 122 | ||

| 1:4 | 50.5 | 128 | ||

| 1:8 | 54.6 | 139 |

Troubleshooting and Optimization Strategies

Addressing Poor Spike and Recovery Results

When spike and recovery results fall outside acceptable ranges, several adjustment strategies can be implemented to optimize assay performance:

Alter the Standard Diluent:

- Use a standard diluent whose composition more closely matches the final sample matrix [2].

- For example, when testing culture supernatants, use culture medium as the standard diluent rather than a simple buffer [2].

- Consider adding carrier proteins like BSA (1%) to the standard diluent to mimic the protein content in biological samples [2].

Modify the Sample Matrix:

- If neat biological samples produce poor recovery, test the sample upon dilution in standard diluent or other logical "sample diluent" [2].

- For serum samples that produce poor spike and recovery, a 1:1 dilution in standard diluent may correct the issue, provided the analyte concentration remains detectable [2].

- Adjust the pH of the sample matrix to match the optimized standard diluent [2].

Sample-Specific Interventions:

- For challenging matrices like chocolate (high in tannins and polyphenols), add extra protein (e.g., fish gelatine or milk powder) to the extraction buffer. The excess protein binds to interfering compounds and makes allergens available for extraction [7].

- Add surfactants (e.g., 0.05% Tween-20) to reduce adsorption and stabilize low-concentration targets, particularly in low-protein matrices like CSF [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful spike and recovery experiments require specific reagents and materials. The following table details essential research reagent solutions and their functions:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Spike and Recovery Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function & Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Recombinant Protein | Serves as the spike analyte; must be identical to the target protein | Use the same lot for all validation experiments [2] |

| Standard Diluent | Base matrix for preparing standard curves and control spikes | Typically a simple buffer (e.g., PBS) [2] |

| Matrix-Matched Diluent | Standard diluent modified to mimic sample matrix composition | Improves recovery by equalizing matrix effects [6] |

| Carrier Proteins (BSA, Gelatine) | Reduces non-specific binding and surface adsorption | Essential for low-protein samples like CSF or urine [2] [7] |

| Surfactants (Tween-20) | Minimizes hydrophobic interactions and surface adsorption | Typically used at 0.05% concentration [6] |

| Protein Stabilizers | Prevents degradation of spiked analyte during processing | Critical for labile proteins [8] |

Regulatory and Industry Perspectives

Validation in Regulatory Contexts

Spike and recovery experiments hold significant importance in regulatory compliance for pharmaceutical development and clinical diagnostics. Regulatory bodies including the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH), FDA, and European Medicines Agency (EMA) provide guidelines on analytical procedure validation that consider recovery values within 75% to 125% of the spiked concentration as acceptable for host cell protein (HCP) ELISAs and related biopharmaceutical applications [3].

The validation requirements differ based on the application context. For in-house developed methods, a full validation is required, including robustness, precision, trueness, limits of quantification, dilutional linearity, parallelism, recovery, selectivity, and sample stability [9]. For commercial assays, a partial validation is typically sufficient, including all parameters except robustness, which should have been addressed by the manufacturer during method development [9].

Industry Standards Across Applications

Acceptable recovery ranges vary across different industries and applications, reflecting the diverse challenges posed by various sample matrices:

- Clinical Diagnostics: Stringent criteria (typically 85-115%) apply due to the medical decision-making implications [9] [6].

- Biopharmaceutical Development: ICH/FDA guidelines allow 75-125% recovery for HCP ELISA, acknowledging the complexity of drug product matrices [3].

- Food Allergen Testing: The Association of Analytical Communities (AOAC) accepts recoveries between 50-150% for challenging food matrices, provided they are consistent, recognizing the extreme diversity and complexity of food samples [7].

Spike and recovery experiments represent a critical validation component for ELISA methods, providing objective evidence that the assay accurately measures the analyte in specific sample matrices. Through systematic spiking of known analyte amounts into biological samples and comparison with standard diluent controls, researchers can identify and quantify matrix interference effects. The consistent application of standardized protocols, coupled with adherence to industry-specific acceptance criteria (typically 80-120% recovery for most research applications), ensures the generation of reliable, reproducible data. When recovery falls outside acceptable ranges, methodological adjustments—such as matrix-matched standard curves, sample dilution, or addition of carrier proteins—can often optimize performance. As such, spike and recovery validation remains an indispensable practice for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to generate quantitatively accurate ELISA data for both basic research and regulatory submissions.

Matrix interference is an inherent challenge in immunoassays like ELISA, where components within a sample matrix (such as proteins, lipids, or salts) disrupt the specific binding between the target analyte and assay antibodies, leading to inaccurate concentration measurements [10]. For researchers and drug development professionals, identifying and quantifying this interference is not optional—it is a critical pillar of assay validation, ensuring that inaccuracies are detected and corrected, thereby safeguarding the reliability of experimental and clinical data [11] [1]. This guide frames the solutions within the essential context of spike and recovery experiments, providing a comparative analysis of methodologies and their performance in delivering accurate results.

Core Experimental Methodologies for Quantification

Three principal experimental protocols are employed to identify and quantify matrix interference, each serving a distinct purpose in assay validation [1].

Spike and Recovery Experiment

This test determines if the sample matrix inhibits or enhances the antibody-analyte binding interaction, providing a direct measure of matrix interference [10] [12].

- Objective: To assess the difference in percent recovery of a known analyte between the standard diluent and the natural sample matrix [1].

- Protocol:

- Spike: Add a known concentration of the purified standard analyte (the "spike") into both the standard diluent and the sample matrix of interest (e.g., plasma, serum) [10] [1].

- Run Assay: Process both the spiked diluent and the spiked matrix through the ELISA.

- Calculate Recovery: Determine the measured concentration from the standard curve and calculate the percent recovery.

- % Recovery = (Measured concentration in spiked matrix / Measured concentration in spiked diluent) × 100 [1].

- Data Interpretation: Ideal recovery is 100%, indicating no matrix interference. Recoveries within 80–120% are generally considered acceptable. Significant deviations outside this range indicate substantial matrix effects that must be addressed [10] [1].

Dilutional Linearity

This experiment assesses whether the matrix effect can be overcome by diluting the sample, and whether the analyte concentration can be reliably measured across different dilutions [1].

- Objective: To verify that a spiked sample, when serially diluted, provides measured concentrations that align with expected values [1].

- Protocol:

- Spike: Introduce a known quantity of standard analyte into the sample matrix at a concentration above the assay's upper detection limit.

- Dilute: Perform a series of dilutions (e.g., 1:2, 1:4, 1:8) using the assay diluent until the predicted concentration falls within the standard curve's range.

- Analyze: Calculate the observed concentration and the percent recovery at each dilution factor [1].

- Data Interpretation: Samples with ideal linearity will show recoveries close to 100% at every dilution. A consistent recovery within the 80–120% range across dilutions confirms that the chosen dilution factor is suitable for accurate measurement [1].

Parallelism

This method validates that the endogenous analyte in a real sample behaves immunologically similarly to the recombinant or purified standard used for the calibration curve [1].

- Objective: To ensure comparable immunoreactivity between the endogenous analyte in a sample and the standard analyte [1].

- Protocol:

- Select Samples: Identify at least three samples with high endogenous concentrations of the analyte.

- Dilute: Perform serial dilutions of these samples using the assay diluent.

- Analyze: Plot the measured concentrations (after applying the dilution factor) against the dilution level [1].

- Data Interpretation: A plot that produces lines parallel to the standard curve indicates that the endogenous and standard analytes are behaving identically. A loss of parallelism suggests differences in immunoreactivity, potentially due to post-translational modifications or other matrix effects [1].

The logical relationship and decision pathway for these experiments can be visualized below.

Comparative Experimental Data and Performance

The following tables summarize quantitative data and performance outcomes from matrix interference experiments, providing a benchmark for researchers.

Table 1: Example Spike and Recovery Data from Various Matrices

This table illustrates how recovery percentages can vary across different sample types, informing the selection of an appropriate minimum dilution [1].

| Sample Matrix | Spike Concentration | % Recovery | Minimum Recommended Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Serum (Extracted) | 2 ng/mL | 102% | Neat |

| Human EDTA Plasma (Extracted) | 1 ng/mL | 90% | Neat |

| Mouse Serum (Extracted) | 0.5 ng/mL | 105.8% | 1:2 |

| Porcine Serum (Extracted) | 0.6 ng/mL | 107.8% | 1:2 |

| Human Saliva (Extracted) | 2.5 ng/mL | 98.7% | 1:2 |

| Banana (Extracted) | 1.25 ng/mL | 87.6% | 1:2 |

Table 2: Dilutional Linearity Analysis of a Spiked Sample

This table demonstrates how recovery can improve at certain dilutions, helping to identify the optimal working range [1].

| Dilution | Expected (pg/mL) | Observed (pg/mL) | Recovery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neat | — | 390.8 | — |

| 1:2 | 195.4 | 194.6 | 100% |

| 1:4 | 97.7 | 105.1 | 108% |

| 1:8 | 48.8 | 67.0 | 137% |

| 1:16 | 24.4 | 27.9 | 114% |

| 1:32 | 12.2 | 12.1 | 99% |

Table 3: Performance of Mitigation Strategies

A comparison of common techniques used to overcome matrix interference after its identification.

| Mitigation Strategy | Principle | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Dilution [10] [11] | Reduces concentration of interfering components | Simple, cost-effective | Requires analyte to be at a high enough concentration |

| Matrix-Matched Calibration [10] [11] | Uses standards diluted in the analyte-free sample matrix | Corrects for matrix effects on the standard curve | Can be difficult to obtain a true "blank" matrix |

| Buffer Exchange [11] | Physically removes interfering components via chromatography | Effective for salts, lipids, and small molecules | Adds a processing step; risk of analyte loss |

| Sample Neutralization [10] | Adjusts sample pH to the optimal range for the assay | Corrects for pH-specific interference | Does not address other types of interference |

| ELISA Protocol Modification [10] | Alters incubation times, volumes, or steps | Can improve signal-to-noise without extra steps | Requires re-validation of the modified protocol |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successfully navigating matrix interference requires a suite of key reagents and materials. The following table details these essential components and their critical functions in validation and mitigation.

| Item | Function in Identifying/Quantifying Interference |

|---|---|

| Analyte-Free Matrix | Serves as the ideal, but often difficult-to-obtain, negative matrix control and base for spiking experiments [13]. |

| Purified Standard Analyte | The known quantity of protein used for "spiking" in recovery and linearity experiments [1]. |

| Assay Diluent | The buffer used to reconstitute standards and, potentially, to dilute samples. Its composition is critical for minimizing nonspecific binding [10] [11]. |

| Blocking Buffers | Solutions containing proteins (e.g., BSA, skimmed milk) or other agents to cover unsaturated binding sites on the plate, reducing background noise [11] [14]. |

| Positive Control | A sample with a known concentration of analyte, used to verify the assay is functioning correctly [13] [15]. |

| Negative Matrix Control | A sample matrix guaranteed to be free of the analyte, used to determine the signal contribution from the matrix itself [13]. |

The integrated workflow for method selection based on experimental data is outlined below.

The systematic identification and quantification of matrix interference through spike and recovery, dilutional linearity, and parallelism experiments are non-negotiable steps in robust ELISA validation. The data derived from these protocols empower researchers to select evidence-based mitigation strategies, ensuring that the final assay delivers accurate, reliable, and reproducible quantification of biomarkers and therapeutics across diverse biological matrices.

In quantitative Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays (ELISAs), the accurate measurement of analytes depends heavily on the liquid environment in which the assay is performed. Two critical but distinct liquid environments are the sample matrix and the standard diluent. The sample matrix is the natural biological fluid containing the analyte of interest, such as serum, plasma, or urine. Its complex composition can significantly interfere with assay accuracy. In contrast, the standard diluent is a defined buffer solution used to prepare the standard curve from purified analyte. The fundamental challenge in ELISA validation arises from the differences between these two environments, which can lead to inaccurate quantification. Spike and recovery experiments serve as a crucial methodology to detect, quantify, and correct for these discrepancies, ensuring the reliability of assay results [2] [1].

Defining the Key Components

Sample Matrix

The sample matrix refers to the native biological sample in which the analyte is found.

- Composition: A complex mixture of components such as proteins (e.g., albumin, immunoglobulins), lipids, carbohydrates, salts, and metabolites [16] [17] [10].

- Function: Serves as the medium for the test sample, containing the endogenous analyte.

- Sources: Common matrices include serum, plasma, urine, saliva, and cell culture supernatants [14].

- Challenge: Components within the matrix can interfere with the antibody-antigen binding in the ELISA through various mechanisms, leading to what is known as the "matrix effect" [17] [10]. This can cause either an artificial increase (false positive) or decrease (false negative) in the measured analyte concentration [10].

Standard Diluent

The standard diluent is a specially formulated buffer solution.

- Composition: Typically a simple, defined solution like phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), often containing a carrier protein such as Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) and other stabilizing agents [18] [16].

- Function: Used to reconstitute and create serial dilutions of the highly purified standard (calibrator) analyte for generating the standard curve [18] [2].

- Objective: To provide an ideal and consistent environment for the antibody-ant interaction, free from interfering substances, thereby establishing a reference for quantification [2].

The table below summarizes the core differences between these two components.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison Between Sample Matrix and Standard Diluent

| Feature | Sample Matrix | Standard Diluent |

|---|---|---|

| Composition | Complex, variable biological fluid | Simple, defined buffer solution |

| Components | Proteins, lipids, salts, metabolites [17] [10] | Buffer salts, carrier protein (e.g., BSA) [18] |

| Primary Role | Holds the endogenous analyte in its native state | Dilutes the purified standard to create a calibration curve |

| Consistency | Highly variable between individuals and samples | Consistent and reproducible |

| Ideal Use | Measuring unknown analyte concentrations in test samples | Creating the standard curve for quantitative interpolation |

The Interaction Problem: Matrix Effects

A core assumption in ELISA is that the analyte, whether in the standard diluent or the sample matrix, behaves identically. However, the complex composition of the sample matrix can violate this assumption. Matrix effects occur when substances in the sample interfere with the assay, altering the detected signal independently of the actual analyte concentration [17] [10].

These effects can stem from:

- Plasma/serum proteins like albumin, complement proteins, or fibrinogen [10].

- Lipids (e.g., steroids) and carbohydrates [16] [10].

- Variations in pH, salt concentration, or sample viscosity [16] [17].

- Direct interactions where interfering substances bind to the analyte or the antibodies, blocking epitopes [10].

When the standard curve is generated in an idealized diluent but samples are run in a complex matrix, the difference in recovery can lead to systematic over- or under-estimation of the true analyte concentration [2]. The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow designed to diagnose this specific problem.

Experimental Protocol: Spike and Recovery

The spike and recovery experiment is the definitive method to quantify the impact of the sample matrix on assay accuracy [2] [1] [16].

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Spike and Recovery

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Matrix | The test biological fluid being validated. | Pooled or individual donor serum/plasma [2]. |

| Standard Diluent | The buffer used for the standard curve. | PBS with 1% BSA [18] [16]. |

| Purified Analyte Standard | A known quantity of the target protein for spiking. | Recombinant protein [2] [10]. |

| ELISA Kit/Reagents | Core assay components. | Coated plate, detection antibodies, substrate [14]. |

| Sample Diluent | Buffer used to dilute samples; may differ from standard diluent. | Optimized to reduce matrix interference [18]. |

Step-by-Step Methodology

Spike Preparation:

- Sample Matrix Spike: Add a known, physiologically relevant concentration of the purified analyte standard directly into the undiluted sample matrix [2] [1].

- Standard Diluent Spike: Add the same known concentration of the purified analyte standard into the standard diluent used for the standard curve. This serves as the control [2].

Assay Execution:

Data Calculation:

- Calculate the concentration of the spiked samples based on the standard curve.

Determine the % Recovery using the following formula [16]:

% Recovery = (Spiked Sample Concentration - Unspiked Sample Concentration) / Spiked Standard Diluent Concentration × 100

Data Interpretation and Acceptance Criteria

The recovery percentage indicates the degree of matrix interference.

- ~100% Recovery (Ideal): Components in the sample matrix do not interfere with analyte detection. The sample matrix and standard diluent are effectively equivalent for the assay [1].

- >120% or <80% Recovery (Problematic): Indicates significant matrix effects. A low recovery suggests suppression of the signal (e.g., blocking of antibody binding), while a high recovery suggests signal enhancement [1] [16].

The acceptable recovery range is typically 80-120%, though specific assays may have stricter limits [1] [16] [10]. The following table provides a concrete example from published data.

Table 3: Example Spike-and-Recovery Data for Recombinant Human IL-1 beta in Human Urine [2]

| Sample (n=9) | Low Spike (15 pg/mL) | Medium Spike (40 pg/mL) | High Spike (80 pg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diluent Control (Recovered Conc.) | 17.0 pg/mL | 44.1 pg/mL | 81.6 pg/mL |

| Mean Urine Recovery (Recovered Conc.) | 14.7 pg/mL | 37.8 pg/mL | 69.0 pg/mL |

| Mean Recovery % | 86.3% | 85.8% | 84.6% |

| Interpretation | Within acceptable range | Within acceptable range | Within acceptable range |

Resolving Matrix Interference Issues

When spike-and-recovery results fall outside the acceptable range, several strategies can be employed to mitigate matrix effects.

Sample Dilution: Diluting the sample in the standard diluent or a specific sample diluent is the most common and effective approach. This reduces the concentration of interfering substances while ideally keeping the analyte within the detection range of the assay [16] [17] [10]. The optimal Minimum Required Dilution (MRD) must be determined empirically [10].

Matrix-Matched Calibration: The standard curve is prepared in a matrix that closely matches the test sample, such as analyte-free (stripped) serum or a pool of normal serum. This ensures that both standards and samples are exposed to the same matrix environment, normalizing the effects [4] [16] [17].

Alternative Diluents: Using a different, optimized assay diluent specifically formulated for problematic sample types (e.g., plasma or serum) can help. These commercial diluents may contain components that inhibit specific interferents like thrombin or complement activity [18].

Sample Pre-treatment: For specific issues, neutralizing the sample pH, delipidation, or other forms of clean-up can be performed to remove interferents prior to the assay [10].

The distinction between the sample matrix and the standard diluent is a fundamental concept in the rigorous validation of quantitative ELISAs. The sample matrix, with its inherent complexity and variability, is a primary source of interference that can compromise data accuracy. The spike and recovery experiment is an indispensable tool that directly probes the interaction between these two environments, providing a quantitative measure of matrix effects. By systematically employing this validation technique and applying corrective strategies such as sample dilution or matrix matching, researchers can ensure their ELISA results are both accurate and reliable, thereby upholding the integrity of their scientific and diagnostic conclusions.

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) provides a methodical quantification of specific analytes through antibody-analyte binding affinity and colorimetric development, serving as a fundamental tool in both research and diagnostic settings [14]. For samples validated by ELISAs, high accuracy and reliability in analyte quantification is the expectation; however, samples that have not been validated may not display similar degrees of reliability [1]. The spike-and-recovery experiment is a critical validation method designed to determine whether analyte detection is affected by differences between the standard curve diluent and the biological sample matrix [2]. In this procedure, a known amount of analyte is added ("spiked") into the natural test sample matrix, and the assay is run to measure the response ("recovery") compared to an identical spike in the standard diluent [2] [19]. When this recovery deviates significantly from 100%, it indicates matrix interference that can lead to either over-estimation or under-estimation of the true analyte concentration, potentially compromising experimental conclusions and diagnostic decisions.

Mechanisms and Consequences of Analytic Over-Estimation

Over-estimation of analytes occurs when the measured concentration exceeds the actual amount present in the sample. This phenomenon typically manifests as "over-recovery" (recovery >125%) and can significantly impact data interpretation [19]. The primary mechanism behind over-estimation involves non-specific interference from matrix components that artificially enhance the assay signal. When the drug substance or other matrix component interacts with the capture or detection antibody, this can result in over-recovery values [19]. Such interactions may include cross-reactivity with structurally similar molecules present in the sample matrix or binding interactions that enhance the enzymatic reaction beyond what would occur with the target analyte alone.

The consequences of analytic over-estimation in research and development can be severe:

- Inaccurate potency assessments in biopharmaceutical development, leading to incorrect dosing determinations

- False positive results in diagnostic applications, potentially causing misdiagnosis

- Inflation of biomarker concentrations in research studies, compromising data validity

- Incorrect conclusions about biological processes or disease states

For drug development professionals, these inaccuracies can have cascading effects throughout the development pipeline, potentially resulting in costly course corrections or failed clinical trials when the true analyte concentrations are discovered at later stages.

Mechanisms and Consequences of Analytic Under-Estimation

Under-estimation represents the more commonly observed direction of error in spike-and-recovery experiments, typically appearing as "under-recovery" (recovery <75%) [19]. This phenomenon occurs when components in the sample matrix inhibit the detection of the target analyte, leading to measured values that are lower than the actual concentration. In the cases where interference is detected, it typically manifests as under-recovery of the spiked analyte [19]. The sample matrix may contain components that affect assay response to the analyte differently than the standard diluent, and a spike-and-recovery experiment is designed to assess this difference in assay response [2].

Multiple mechanisms can contribute to analytic under-estimation:

- Matrix effects from substances such as salts, detergents, lipids, or heterophilic antibodies that interfere with antigen-antibody binding [1]

- Protein degradation from enzymatic activity in the sample matrix that breaks down the target analyte before detection

- Sequestration of the analyte by binding proteins or other matrix components, rendering it unavailable for detection

- High background protein concentrations that hinder antibody binding and increase signal-to-noise ratio, resulting in underestimation of the target concentration [4]

The consequences of under-estimation present significant risks across applications:

- Failure to detect clinically relevant biomarkers in diagnostic settings, leading to false negatives

- Underestimation of impurity levels in biopharmaceuticals, potentially compromising drug safety

- Inaccurate pharmacokinetic data due to underestimated drug concentrations

- Invalid conclusions in research studies regarding biological concentrations and responses

For scientists and drug development professionals, these inaccuracies can be particularly problematic when they occur with precious samples that cannot be easily replaced, emphasizing the critical need for proper validation before running definitive experiments [20].

Experimental Protocols for Assessment

Standard Spike-and-Recovery Protocol

The fundamental spike-and-recovery experiment follows a systematic approach to quantify matrix effects [2] [19]:

- Step 1: Prepare a known concentration of the purified analyte (standard) in the standard diluent used for the ELISA standard curve.

- Step 2: Spike this known amount of analyte into the natural sample matrix at 3-4 concentration levels covering the analytical range of the assay [19]. The lowest spiked concentration should be at least 2 times the Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) of the assay [19].

- Step 3: In parallel, prepare an identical spike of the analyte into the standard diluent as a control.

- Step 4: Run both the spiked sample matrix and spiked standard diluent in the ELISA according to the established protocol.

- Step 5: Calculate the recovery percentage using the formula: Recovery % = (Measured concentration in spiked sample - Endogenous concentration in unspiked sample) / Known spiked concentration × 100.

Table 1: Example Spike-and-Recovery Data for Recombinant Human IL-1 Beta in Human Urine Samples [2]

| Sample | No Spike (0 pg/mL) | Low Spike (15 pg/mL) | Medium Spike (40 pg/mL) | High Spike (80 pg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diluent Control | 0.0 | 17.0 | 44.1 | 81.6 |

| Donor 1 | 0.7 | 14.6 | 39.6 | 69.6 |

| Donor 2 | 0.0 | 17.8 | 41.6 | 74.8 |

| Donor 3 | 0.6 | 15.0 | 37.6 | 68.9 |

| Donor 9 | 0.7 | 12.4 | 37.6 | 68.2 |

| Mean Recovery | NA | 86.3% | 85.8% | 84.6% |

Linearity of Dilution Assessment

The linearity-of-dilution experiment provides complementary information about the precision of results for samples tested at different levels of dilution in a chosen sample diluent [2]. This protocol determines whether sample matrices spiked with detection analyte above the upper limit of detection can still provide reliable quantification after dilution within standard curve ranges [1].

- Traditional Method: Use a sample containing a known spike of analyte or a sample with high endogenous levels of the analyte, then test several different dilutions of that sample in the chosen sample diluent [2] [1].

- Alternative Method: Prepare several dilutions of a low-level sample and then spike the same known amount of analyte into each one before testing [2].

- Calculation: Assess recovery by comparing observed versus expected values based on non-spiked and/or neat (undiluted) samples [2].

Table 2: Example Linearity-of-Dilution Results for Human IL-1 Beta Samples [2]

| Sample | Dilution Factor | Observed (pg/mL) × DF | Expected (neat value) | Recovery % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ConA-stimulated cell culture supernatant | Neat | 131.5 | 131.5 | 100 |

| 1:2 | 149.9 | 114 | ||

| 1:4 | 162.2 | 123 | ||

| 1:8 | 165.4 | 126 | ||

| High-level serum sample | Neat | 128.7 | 128.7 | 100 |

| 1:2 | 142.6 | 111 | ||

| 1:4 | 139.2 | 108 | ||

| Low-level serum sample spiked with recombinant IL-1 beta | Neat | 39.3 | 39.3 | 100 |

| 1:2 | 47.9 | 122 | ||

| 1:4 | 50.5 | 128 |

Troubleshooting and Correction Strategies

Addressing Poor Recovery Results

When spike-and-recovery experiments reveal significant deviations from the expected 100% recovery, several methodological adjustments can be implemented to improve accuracy:

Alter the Standard Diluent: Use a standard diluent whose composition more closely matches the final sample matrix [2]. For example, culture medium could be used as the standard diluent if the samples will be culture supernatants [2]. While this approach may decrease assay range, sensitivity, or signal-to-noise ratio compared to previously optimized conditions, it often represents a necessary compromise for accurate quantification.

Modify the Sample Matrix: If neat biological samples produce poor spike and recovery, dilution in standard diluent or other logical "sample diluent" may improve results [2]. For instance, if an undiluted serum sample produces poor recovery, a sample diluted 1:1 in standard diluent may perform better, provided the analyte concentration remains detectable [2].

Matrix pH Adjustment: Better results for a sample matrix may be obtained by altering its pH to match the optimized standard diluent [2].

Protein Supplementation: Adding BSA or other purified protein as a carrier/stabilizer can improve recovery in some matrices by reducing non-specific binding [2].

Establishing Acceptance Criteria

Regulatory and industry guidelines provide frameworks for interpreting spike-and-recovery results:

- ICH, FDA, and EMA Guidelines: Consider recovery values within 75% to 125% of the spiked concentration to be in the acceptable range [19].

- Alternative Criteria: Some sources suggest a slightly narrower range of 80-120% as acceptable [1] [4] [21].

- Parallelism Assessment: %CV within 20-30% of expectations generally display successful parallelism, although the exact percentage should be decided by end users based on their specific application requirements [1].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Spike-and-Recovery Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Analyte Standard | Serves as the spike material of known concentration | Should be identical to the native analyte; requires proper storage to prevent degradation [20] |

| Standard Diluent | Matrix for preparing standard curve and control spikes | Optimized for signal-to-noise performance; may need modification to match sample matrix [2] |

| Sample Diluent | Matrix for diluting biological samples | May differ from standard diluent; optimal composition depends on sample type [2] |

| Matrix-Matched Controls | Assess background interference in specific sample types | Should include the same matrix as test samples for accurate recovery assessment [22] |

| Blocking Buffers | Reduce non-specific binding in assay | Composition (BSA, non-fat milk, etc.) may need optimization for different matrices [2] |

| Microplate Reader | Measure absorbance of colorimetric reaction | Capable of reading at appropriate wavelengths (e.g., 450nm); software for curve fitting essential [14] [4] |

Spike-and-recovery experiments represent an essential component of ELISA validation that directly addresses the critical issue of analytical accuracy in complex biological matrices. The consequences of poor recovery—whether leading to over-estimation or under-estimation of analytes—can fundamentally compromise the validity of experimental data and subsequent conclusions. Through systematic implementation of the described protocols and troubleshooting strategies, researchers and drug development professionals can identify matrix effects, implement appropriate corrections, and generate reliable, quantitative data. As ELISA continues to be a cornerstone technology in both research and clinical applications, rigorous attention to recovery validation remains fundamental to scientific rigor and accurate analyte quantification across diverse sample types.

Within the stringent framework of biopharmaceutical development, demonstrating that an analytical method is "fit-for-purpose" is a regulatory imperative. Assay qualification provides objective evidence that a method consistently produces reliable results suitable for its intended use. This guide explores the critical role of spike and recovery experiments, a cornerstone of immunoassay validation, in meeting regulatory standards from agencies like the FDA and EMA. We will examine its fundamental principles, detailed experimental protocols, and its position within the broader validation paradigm, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to ensure regulatory compliance and data integrity.

Fit-for-purpose assay qualification is the process of demonstrating that an analytical method, such as an Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA), fulfills predefined requirements for a specific application [9]. Unlike full validation for in vitro diagnostics, a fit-for-purpose approach tailors the stringency and extent of validation experiments to the assay's intended role, whether for process development, product release, or characterization [23] [24]. The overarching goal is to generate objective evidence that the method is precise, accurate, and robust enough to support critical decisions in a regulated environment.

Regulatory agencies, including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA), provide guidelines that shape these qualification efforts [25] [9]. Adherence to these standards is not merely a bureaucratic hurdle; it is fundamental to ensuring the safety and efficacy of biopharmaceuticals. A well-qualified Host Cell Protein (HCP) ELISA, for example, gives analysts and regulators confidence that a purification process consistently reduces process-related impurities to safe levels [23]. The consequences of poor validation are severe, potentially leading to the generation of false positive or false negative results, which can compromise product quality and patient safety [24].

The Centrality of Spike and Recovery Experiments

Principles and Definitions

The spike and recovery experiment is a fundamental procedure used to assess the accuracy of an ELISA [2] [25]. Accuracy refers to the closeness of agreement between the measured value and the true value of the analyte [9]. In this experiment, a known amount of a purified reference analyte is introduced ("spiked") into a sample matrix of interest. The assay is then performed, and the measured concentration of the spiked analyte is compared to its expected concentration [2].

The percentage recovery is calculated as follows: % Recovery = (Measured Concentration / Expected Concentration) × 100

This test is essential because the sample matrix (e.g., serum, drug substance, in-process harvest) can contain components that interfere with the antibody-antigen interaction, leading to an overestimation (over-recovery) or underestimation (under-recovery) of the target impurity [25]. Factors such as high or low pH, high protein or salt concentration, or the presence of detergents or organic solvents are known to cause such interference [25].

Regulatory Acceptance Criteria

Regulatory guidelines provide clear benchmarks for acceptable spike and recovery performance. According to ICH, FDA, and EMA guidelines, recovery values within 75% to 125% of the spiked analyte concentration are generally considered acceptable [25]. This range ensures that the assay delivers accurate quantitation despite the potential complexities of the sample matrix.

Experimental Protocol for Spike and Recovery

A robust spike and recovery experiment must be performed for every unique sample matrix to be tested in the ELISA [25]. The following provides a detailed, step-by-step methodology.

Preliminary Requirement: Dilution Linearity and MRD

Before performing spike and recovery, it is recommended to first conduct dilution linearity studies. This experiment establishes that the condition of antibody excess is met and determines the Minimum Required Dilution (MRD) for the sample, which is the dilution that minimizes matrix interference while keeping the analyte within the assay's quantifiable range [25].

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Sample Preparation: Prepare the neat (undiluted) sample matrix.

- Spike Solution: Prepare a concentrated stock solution of the purified analyte (e.g., recombinant protein or purified HCP) in an appropriate diluent.

- Spiking: Spike the sample matrix at 3-4 concentration levels covering the analytical range of the assay. For instance, to achieve a final spike concentration of 20 ng/mL, add 1 part of a 100 ng/mL standard into 4 parts of the neat sample [25].

- Control Samples: Prepare two critical control samples in parallel:

- Matrix Blank: The sample matrix spiked with a "zero standard" (the diluent used for the spike solution) to determine the endogenous level of the analyte.

- Diluent Control: The standard diluent spiked with the same amount of analyte to represent the 100% recovery baseline.

- Assay Execution: Run the complete ELISA protocol on all spiked samples and controls.

- Data Calculation:

- Subtract the value of the Matrix Blank from the corresponding spiked sample to determine the net measured concentration attributable only to the spike.

- Calculate the % Recovery for each spike level using the Diluent Control as the expected value.

Table 1: Example Spike and Recovery Data for an HCP ELISA in a Final Product Matrix [25]

| Sample Description | Spike Concentration (ng/mL) | Total HCP Measured (ng/mL) | Net Measured Spike (ng/mL) | % Recovery |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matrix Blank | 0 | 6.0 | --- | --- |

| Diluent Control | 20 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 100.0 |

| Final Product | 20 | 25.0 | 19.0 | 95.0 |

Troubleshooting Poor Recovery

Poor recovery indicates matrix interference. Two primary adjustments can be made to the method [2]:

- Alter the Standard Diluent: Use a standard diluent whose composition more closely matches the final sample matrix (e.g., using culture medium for culture supernatant samples).

- Alter the Sample Matrix: Dilute the sample further in the standard diluent or adjust its pH. Adding a carrier protein like BSA can also stabilize the analyte and improve recovery.

The following workflow diagrams the logical process of performing and interpreting a spike and recovery experiment.

Integration within the Broader Validation Paradigm

Spike and recovery is a critical component of accuracy, but it is only one part of a comprehensive assay qualification. The following diagram illustrates its relationship with other essential validation parameters.

A fit-for-purpose qualification typically evaluates the following parameters in concert with spike and recovery [23] [24] [9]:

- Precision: The closeness of agreement between a series of measurements. This includes intra-assay precision (repeatability within a single plate) and inter-assay precision (reproducibility across different days, operators, or reagent lots) [24].

- Specificity: The ability of the assay to measure the analyte accurately in the presence of other components, such as the product protein, related isoforms, or formulation excipients. This is often confirmed via cross-reactivity studies or by using a negative control [24].

- Sensitivity: The lowest amount of analyte that can be reliably distinguished from zero, defined as the Lower Limit of Detection (LOD). The Lower Limit of Quantification (LLOQ) and Upper Limit of Quantification (ULOQ) define the assay range [24].

- Linearity and Range: The capacity of the assay to obtain results that are directly proportional to the analyte concentration within the LLOQ and ULOQ [2] [24].

- Robustness: A measure of the assay's capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters (e.g., incubation times, temperatures), indicating its reliability during routine use [9].

Comparison of Analytical Platforms for Biomolecular Detection

While ELISA is the established workhorse for quantitative protein analysis, alternative technologies offer different advantages and limitations. The table below provides a comparative overview, with a focus on data provided for Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR).

Table 2: Platform Comparison for Biomolecular Detection (ELISA vs. SPR) [26]

| Parameter | ELISA | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) |

|---|---|---|

| Data Obtained | End-point concentration | Real-time affinity (KD) and kinetics (ka, kd) |

| Label Requirement | Requires enzyme-conjugated antibodies | Label-free |

| Experiment Length | Typically > 1 day | Significantly faster; minutes to hours |

| Detection of Low-Affinity Interactions | Poor (washed away in steps) | Effective |

| Throughput | High (96- or 384-well) | Moderate (varies by instrument) |

| Cost & Accessibility | Low cost, widely accessible | High upfront cost, lower operating costs for some systems |

| Best Suited For | High-throughput quantification of analytes in many samples | Detailed characterization of binding mechanisms |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful assay qualification relies on a suite of critical reagents and materials. The following table details key components and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for ELISA Qualification

| Item | Function in Qualification |

|---|---|

| Reference Standard | A purified analyte of known concentration and identity used to prepare the standard curve and spiking solutions; essential for defining accuracy [24]. |

| Critical Coating/Capture Antibody | The antibody immobilized on the plate to specifically bind the target analyte; its affinity and specificity are paramount [27]. |

| Detection Antibody | The antibody that binds the captured analyte; often conjugated to an enzyme (e.g., HRP) for signal generation. Must recognize a different epitope than the capture antibody in a sandwich ELISA [27]. |

| Validated Sample Diluent | The buffer used to dilute samples and standards. Its composition is optimized to match the sample matrix and minimize interference, a key factor in spike and recovery [2]. |

| Blocking Buffer | A solution of irrelevant protein (e.g., BSA) used to cover all unsaturated binding sites on the microplate to prevent non-specific binding and high background [27]. |

| Validated Substrate | The reagent converted by the reporter enzyme (e.g., HRP) into a measurable colorimetric, chemiluminescent, or fluorescent signal [27]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Samples | Samples with known, predetermined analyte concentrations used to monitor the precision and accuracy of each assay run [24]. |

Spike and recovery analysis is a non-negotiable element of fit-for-purpose assay qualification, serving as a direct experimental probe into the accuracy of an ELISA within a specific sample matrix. Its proper execution, guided by clearly defined regulatory acceptance criteria, is fundamental to generating data that instills confidence in the safety and efficacy assessments of biopharmaceuticals. While this guide has detailed its central role, it is crucial to remember that spike and recovery is one pillar in a comprehensive validation structure that also includes precision, specificity, and sensitivity. Together, these elements form an objective, evidence-based foundation that supports the entire drug development process, from early research to final product release, ensuring compliance with global regulatory standards and, ultimately, protecting patient health.

Executing a Spike and Recovery Experiment: A Step-by-Step Protocol

Establishing the Minimum Required Dilution (MRD) is a critical pre-experimental step in ELISA validation that ensures accurate quantification of analytes by mitigating matrix interference. This guide objectively compares the performance of different sample preparation strategies and diluents, providing supporting experimental data to help researchers identify optimal dilution factors. Within the broader context of spike and recovery experiments for ELISA validation, proper MRD determination serves as the foundation for reliable assay performance, enabling researchers to generate pharmacologically relevant data that complies with regulatory standards.

The Minimum Required Dilution (MRD) represents the lowest sample dilution that effectively minimizes matrix effects while maintaining the analyte concentration within the assay's quantifiable range [28]. In ELISA validation, determining the MRD is not merely a procedural step but a fundamental prerequisite that directly impacts the accuracy and reliability of all subsequent data, including spike and recovery results. Complex biological matrices such as serum, plasma, and urine contain numerous interfering components—including heterophilic antibodies, complement factors, lipids, and other proteins—that can profoundly affect antibody-binding kinetics and generate inaccurate measurements [24] [29].

Establishing the MRD represents a methodological compromise between sufficiently minimizing matrix interference and maintaining adequate analyte concentration for detection. A dilution that is too low may fail to eliminate matrix effects, while excessive dilution may push analyte concentrations below the assay's limit of quantification [28]. The MRD determination process empirically identifies this optimal balance for each unique sample matrix, ensuring that the condition of antibody excess is maintained across the diverse array of analytes present in samples such as Host Cell Proteins (HCPs) [28]. This is particularly crucial in drug development contexts, where accurate impurity quantification directly impacts product characterization and safety assessment.

Theoretical Framework: The Role of MRD in Assay Validation

Relationship Between MRD and Spike/Recovery Experiments

MRD determination and spike/recovery validation form an interdependent validation sequence in ELISA development. The MRD establishes the dilution framework within which spike/recovery experiments are conducted, creating a foundation for accurate recovery assessment [29] [28]. Without proper MRD establishment, spike/recovery results may be compromised by residual matrix effects, leading to either overestimation ("over-recovery") or underestimation ("under-recovery") of the actual analyte [29].

The conceptual relationship between these validation components follows a sequential logic: MRD determination first identifies the dilution that neutralizes matrix interference, then spike/recovery experiments verify that the chosen dilution yields accurate quantification of known analyte concentrations [2] [29]. This systematic approach ensures that the assay delivers reliable performance across different sample types and matrices, confirming that both the dilution factor and the sample matrix are appropriate for the intended application [28].

Consequences of Inadequate MRD Determination

Failure to establish appropriate MRD can lead to several analytical challenges that compromise data integrity. Poor dilution linearity may manifest when antibody excess is not maintained for one or more analytes in the sample, particularly in assays detecting multiple components such as HCP ELISAs [28]. This can result in a "high-dose hook effect" where high concentrations of specific analytes saturate their cognate antibodies, leading to under-quantification [28]. Additionally, certain "hitchhiker proteins" that interact with the product or become enriched during purification processes can further interfere with assay linearity [28].

Matrix components in product formulation buffers—such as extreme pH, high protein or salt concentrations, detergents, or organic solvents—can also interfere with ELISA quantification, resulting in either over- or under-estimation of the true analyte concentration [29] [28]. These interference effects typically manifest as non-parallelism in dilution curves, indicating differential immunoreactivity between the native protein in the sample and the reference standard protein used for calibration [24]. Such discrepancies may arise from post-translational modifications, protein complexation, or other matrix effects that alter antibody binding affinity [1].

Experimental Protocol for MRD Determination

Sample Preparation and Dilution Scheme

The MRD determination process begins with preparing serial dilutions of the test sample using an appropriate assay diluent. The recommended approach involves creating a doubling dilution series (e.g., neat, 1:2, 1:4, 1:8, etc.) until the predicted analyte concentration falls below the assay's lower limit of quantification [28] [1]. This dilution series should be prepared using the same diluent employed for standard curve generation to maintain consistency, unless preliminary data indicates that an alternative diluent provides superior performance [2].

For each sample type intended for routine testing—including in-process samples and final drug substance—separate MRD determinations should be performed [28]. This matrix-specific approach is necessary because different sample types may contain varying levels of interfering components that affect the assay differently. When working with complex samples containing multiple analytes, such as HCPs, it is advisable to pool multiple lots of samples to create a representative mixture that averages matrix effects across production batches [13]. This pooled sample then serves as the basis for the dilution linearity experiment, ensuring that the established MRD will be applicable across future sample variations.

Experimental Workflow and Data Collection

The following diagram illustrates the complete MRD determination workflow:

After running the ELISA assay, the dilution-corrected concentration for each dilution is calculated by multiplying the measured concentration by the corresponding dilution factor [28]. For example, a 1:4 dilution that yields a measured concentration of 78 ng/mL would have a dilution-corrected value of 312 ng/mL (78 × 4). These corrected values should remain relatively constant across dilutions when matrix effects have been sufficiently minimized and antibody excess conditions are met [28].

Data Interpretation and MRD Selection Criteria

The MRD is identified as the most concentrated (lowest) dilution in the series where the dilution-corrected values stabilize within an acceptable variance range [28]. According to industry standards, acceptable dilution linearity is achieved when corrected analyte concentrations vary no more than ±20% between doubling dilutions, provided the measured concentration (before correction) remains above two times the assay's limit of quantification (LOQ) [28].

The percentage change between successive dilutions is calculated using the formula: [(Corrected Valueₐ - Corrected Valueₐ₋₁) / Corrected Valueₐ₋₁] × 100% [28]. For instance, if a 1:2 dilution yields a corrected value of 233 ng/mL and the subsequent 1:4 dilution gives 312 ng/mL, the percent change would be calculated as [(312 - 233) / 233] × 100% = 34%, which exceeds the acceptable ±20% threshold [28]. In such cases, further dilution would be necessary until the percent change falls within the acceptable range.

Comparative Performance Data

Representative MRD Determination Data

The following table presents experimental data from a typical MRD determination study, illustrating how sample dilution affects corrected analyte concentrations and the subsequent identification of the appropriate MRD:

Table 1: Sample Dilution Linearity Data for MRD Determination [28]

| Sample Dilution | Dilution-Corrected Value (ng/mL) | % Change from Previous Dilution | Meets ±20% Criterion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neat (undiluted) | 146 | NA | No |

| 1:2 | 233 | 60% | No |

| 1:4 | 312 | 34% | No |

| 1:8 | 361 | 16% | Yes |

| 1:16 | 356 | 1% | Yes |

| 1:32 | 370 | 4% | Yes |

| 1:64 | Not calculated (<2×LOQ) | NA | No |

Based on this data, the MRD would be established at 1:8 dilution, as it represents the most concentrated sample where the dilution-corrected values stabilize within the acceptable variance range (±20%) and remain above the assay's quantifiable limit [28]. The reported HCP concentration for this sample would be calculated as the average of the results at and below the MRD that remain above 2×LOQ (in this case, the average of 312, 361, 356, and 370 = 350 ng/mL) [28].

Comparison of Sample Matrices and Dilution Requirements

Different sample matrices demonstrate varying dilution requirements due to their unique composition and potential interfering components. The following table compares MRD results across different biological matrices:

Table 2: Comparison of MRD Across Sample Matrices [1]

| Sample Matrix | Endogenous Analyte Concentration | Established MRD | Recovery at MRD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Serum | Moderate | Neat | 83-124% |

| Mouse Serum | Low | 1:2 | 90-116% |

| Porcine Serum | High | 1:2 | 103-113% |

| Human Saliva | Variable | 1:2 | 83-108% |

| Fruit Extract | Variable | 1:2 | 88-116% |

This comparative data illustrates how matrix complexity and endogenous analyte levels influence the required dilution to achieve optimal recovery. Complex matrices such as serum typically require greater dilution (1:2) compared to simpler buffers, which may be tested neat [1]. The recovery percentages following MRD establishment should ideally fall within 75-125% according to ICH, FDA, and EMA guidelines [29].

Research Reagent Solutions for MRD Studies

Successful MRD determination requires carefully selected reagents and materials designed to maintain assay integrity while identifying optimal dilution factors. The following table outlines essential research reagent solutions for robust MRD studies:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MRD Determination

| Reagent Solution | Function in MRD Studies | Performance Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Assay Diluent | Base solution for preparing sample dilutions; should match standard diluent when possible | Composition should approximate sample matrix without interfering components; may contain stabilizing proteins like BSA [2] |

| Coated ELISA Plates | Solid phase for immuno-capture reaction | Should have high protein-binding capacity (>400 ng/cm²) and low well-to-well variation (CV <5%); clear for colorimetric, black/white for fluorescent detection [27] |

| Coating Buffer | Immobilizes capture antibody or antigen | Typically carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.4) or PBS (pH 7.4); composition affects binding efficiency and stability [27] |

| Blocking Buffer | Covers unsaturated binding sites to prevent nonspecific binding | Various solutions including BSA, casein, or proprietary commercial formulations; requires optimization for specific sample types [24] [27] |

| Washing Buffer | Removes unbound reagents between steps | Typically PBS or Tris-based with detergent (e.g., Tween-20); critical for reducing background signal [24] |

| Reference Standard | Known concentration of analyte for standard curve generation | Should be identical to natural analyte when possible; serial dilutions must span assay dynamic range [24] [13] |

Troubleshooting and Optimization Strategies

Addressing Poor Dilution Linearity

When samples fail to demonstrate acceptable dilution linearity (±20% variance) even at high dilutions, several optimization strategies may be employed. The first approach involves further dilution of the sample until the corrected values stabilize, provided the measured concentration remains above 2×LOQ [28]. If additional dilution does not resolve the issue, modification of the assay protocol or alteration of the sample diluent may be necessary to improve accuracy for problematic sample types [28].

For persistent linearity issues, consider adjusting the standard diluent to more closely match the final sample matrix composition [2]. For example, if analyzing culture supernatants, using culture medium as the standard diluent may improve parallelism. Alternatively, modifying the sample matrix itself by adjusting pH to match the optimized standard diluent or adding carrier proteins like BSA can correct recovery problems [2]. In cases where the sample contains high background proteins (e.g., serum albumin), the optimal standard diluent may contain added protein while the sample diluent may not require additional protein [2].

Regulatory Considerations and Acceptance Criteria

When establishing MRD for regulated environments, adherence to established guidelines is essential. Regulatory agencies including ICH, FDA, and EMA specify that spike recovery values following proper dilution should fall within 75-125% of the expected concentration [29]. Similarly, dilution linearity is considered acceptable when corrected concentrations vary no more than ±20% between doubling dilutions [28].

For samples demonstrating significant product or matrix interference despite optimization attempts, it may be necessary to implement additional sample processing steps, such as extraction, precipitation, or chromatography, to remove interfering components before ELISA analysis [13]. In such cases, spiked matrix samples become essential for evaluating extraction efficiency by comparing the detected quantity of analyte after extraction to the known input quantity [13].

Establishing the Minimum Required Dilution represents a foundational element in the ELISA validation workflow, creating the necessary conditions for reliable spike/recovery assessment and accurate sample quantification. Through systematic dilution linearity testing and adherence to defined acceptance criteria (±20% variance between doubling dilutions), researchers can identify the optimal balance between minimizing matrix effects and maintaining adequate analyte detectability. The comparative data presented in this guide demonstrates how MRD requirements vary across sample matrices, emphasizing the need for matrix-specific validation approaches. By implementing the detailed protocols, reagent solutions, and troubleshooting strategies outlined herein, researchers can ensure their ELISA methods generate pharmacologically relevant data compliant with regulatory standards, ultimately supporting robust analytical decision-making in drug development and biomedical research.

In enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) development, the spike-and-recovery experiment is a fundamental validation tool used to assess assay accuracy and the influence of sample matrix effects. This method determines whether the biological sample matrix (e.g., serum, plasma, or tissue homogenate) affects the detection of the target analyte compared to the standard diluent used to generate the calibration curve [2] [1]. The core principle involves adding a known quantity of the purified analyte ("spiking") into the natural sample matrix and then measuring the amount recovered by the assay. Discrepancies between the measured value and the expected value indicate that components within the sample matrix are interfering with antigen-antibody binding, potentially leading to inaccurate quantification [2]. Addressing these issues is critical for ensuring that ELISA results are reliable, particularly in regulated environments like drug development [22].

The selection of appropriate spike concentrations is paramount to this process. A well-designed concentration series that covers the analytical range of the assay can diagnose problems and confirm the assay's robustness across the entire range of expected sample values, from the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) to the upper limit of quantification (ULOQ) [1]. This guide will objectively compare strategies for selecting these concentrations, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols.

Theoretical Framework and Strategic Approaches

The strategic selection of spike concentrations is guided by the intended use of the ELISA. The sample matrix itself can cause interference through various mechanisms, including the presence of binding proteins, proteases, or high levels of lipids or bilirubin that may affect antibody affinity or the function of the reporter enzyme [2] [1]. The goal of spike-and-recovery is to quantify this interference.

Two primary strategic approaches exist for selecting spike concentrations, each serving a distinct purpose in assay validation:

- Covering the Analytical Range: This strategy involves spiking the sample matrix at multiple concentration levels that span the dynamic range of the standard curve. This is the most comprehensive approach as it verifies assay accuracy at low, mid, and high concentrations, ensuring the entire assay range is valid for the sample type [2] [1]. It is the recommended approach for full method validation.

- Bracketing the Minimum Required Performance Level (MRPL): In some applications, particularly in regulatory screening for residues like chloramphenicol in food, the critical requirement is to ensure accurate detection at a specific threshold. Here, spiking concentrations are chosen to bracket this MRPL (e.g., 0.15 to 0.60 ng/g, as demonstrated in a study on crab and shrimp muscle) to confirm the assay's performance at the level of regulatory concern [30].

The following table compares the strategic considerations for these two approaches:

Table 1: Strategic Approaches for Selecting Spike Concentrations

| Strategy | Objective | Typical Spike Levels | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Covering the Analytical Range [2] [1] | To validate assay accuracy across the entire standard curve, from Lower Limit of Quantification (LLOQ) to Upper Limit of Quantification (ULOQ). | Low, Medium, and High levels (e.g., near LLOQ, mid-point, and near ULOQ of the standard curve). | Full method validation for drug development, biomarker quantification, and research requiring precise measurement across a wide concentration range. |

| Bracketing the MRPL [30] | To confirm that the assay reliably detects the analyte at a specific, critically important concentration. | Concentrations slightly above and below the mandatory performance level (e.g., 0.15 and 0.60 ng/g for a 0.30 ng/g MRPL). | Regulatory screening and monitoring where detection at a defined threshold is legally required. |

The Critical Role of the Standard Diluent

A key principle in spike-and-recovery is the comparison of the analyte's behavior in the sample matrix versus the standard diluent [2]. The ideal recovery is observed when the standard diluent closely mimics the sample matrix. If the standard is diluted in a simple buffer like PBS while the sample is a complex matrix like serum, differences in recovery are likely. To mitigate this, the standard can be diluted in a matrix that more closely matches the sample, such as culture medium for cell supernatant samples or a defined solution of irrelevant protein like BSA for serum samples [2]. However, this may involve a trade-off with the assay's signal-to-noise ratio.

Experimental Protocol for Spike-and-Recovery

The following is a detailed, step-by-step protocol for performing a spike-and-recovery experiment designed to cover the analytical range.

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Spike-and-Recovery Experiments

| Item | Function/Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Analyte | The known quantity of protein or antigen used for spiking. Should be identical or highly similar to the endogenous analyte. | Recombinant SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein [31]. |

| Sample Matrix | The biological fluid or extract being validated (e.g., serum, plasma, urine, tissue homogenate). | Pre-pandemic human serum [32], crab and shrimp muscle [30]. |

| Standard Diluent | The buffer used to prepare the standard curve. | Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) often with a carrier protein like 1% BSA [2]. |

| Assay Buffer | The diluent used to prepare sample and standard serial dilutions. | PBS with 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T) [32]. |